David Farragut

| David Glasgow Farragut | |

|---|---|

| July 5 1801 – August 14 1870 | |

|

|

| Place of birth | Campbell's Station, Tennessee |

| Place of death | Portsmouth, New Hampshire |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1810–70 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Commands held | European Squadron Western Gulf Blockading Squadron |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 American Civil War

|

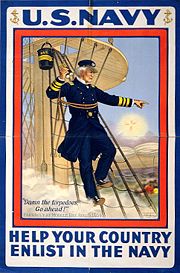

David Glasgow Farragut (July 5 1801 – August 14 1870) was a senior or "flag" officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and full admiral of the Navy. He is remembered in popular culture for his order at the Battle of Mobile Bay, usually paraphrased: "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!".[1]

Contents[hide] |

Farragut was born to Jorge and Elizabeth Shine Farragut at Lowe's Ferry on the Holston (now Tennessee) River a few miles south east of Campbell's Station, near Knoxville, Tennessee, where his family lived. His father operated the ferry and was a cavalry officer in the Tennessee militia. Jorge Farragut (1755 – 1817), a Spanish merchant captain from Minorca, son of Antonio Farragut and Juana Mesquida, had previously joined the American Revolutionary cause after arriving in America in 1776. Jorge Farragut married Elizabeth Shine (b.1765) from North Carolina and moved west to Tennessee after serving in the American Revolution. David's birth name was James, but it was changed in 1812, following his adoption by future naval Captain David Porter in 1808 (which made him the foster brother of future Civil War Admiral David Dixon Porter and Commodore William D. Porter).

David Farragut entered the Navy as a midshipman on December 17 1810. In the War of 1812, when only 12 years old, he was given command of a prize ship taken by USS Essex and brought her safely to port. He was wounded and captured during the cruise of the Essex by HMS Phoebe in Valparaiso Bay, Chile on March 28 1814, but was exchanged in April 1815. Through the years that followed, in one assignment after another, he showed the high ability and devotion to duty that would allow him to make a great contribution to the Union victory in the Civil War and to write a famous page in the history of the United States Navy.

Civil War

In command of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, with his flag on the USS Hartford, in April 1862 he ran past Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip and the Chalmette, Louisiana batteries to take the city and port of New Orleans, Louisiana on April 29 of that year, a decisive event in the war. His country honored its great sailor after New Orleans by creating for him the rank of rear admiral on July 16 1862, a rank never before used in the U.S. Navy. Before this time, the American Navy had resisted the rank of admiral, preferring the term "flag officer", to separate it from the traditions of the European navies. Later that year he passed the batteries defending Vicksburg, Mississippi. Farragut had no real success at Vicksburg; one makeshift Confederate ironclad forced his flotilla of 38 ships to withdraw in July 1862.

He was a very aggressive commander but not always cooperative. At the Siege of Port Hudson the plan was that Farragut's flotilla would pass by the guns of the Confederate stronghold with the help of a diversionary land attack by the Army of the Gulf, commanded by General Nathaniel Banks, to commence at 8:00 am on March 15 1863. Farragut unilaterally decided to move the timetable up to 9:00 pm on March 14, and initiated his run past the guns before Union ground forces were in position. By doing so, the uncoordinated attack allowed the Confederates to concentrate on Farragut's flotilla and inflict heavy damage on his warships.

Farragut's battle group was forced to retreat with only two ships able to pass the heavy cannon of the Confederate bastion. After surviving the gauntlet, Farragut played no further part in the battle for Port Hudson, and General Banks was left to continue the siege without advantage of naval support. The Union Army made two major attacks on the fort, and both were repulsed with heavy losses. Farragut's flotilla was splintered, yet was able to blockade the mouth of the Red River with the two remaining warships, but not efficiently patrol the section of the Mississippi between Port Hudson and Vicksburg. Farragut's decision thus proved costly to the Union Navy and the Union Army, which suffered the highest casualty rate of the Civil War at the Battle of Port Hudson.

Vicksburg surrendered on July 4 1863, leaving Port Hudson as the last remaining Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. General Banks accepted the surrender of the Confederate garrison at Port Hudson on July 9 1863, ending the longest siege in US military history. Control of the Mississippi River was the centerpiece of Union strategy to win the war, and with the surrender of Port Hudson the Confederacy was now severed in two.

On August 5 1864, Farragut won a great victory in the Battle of Mobile Bay. Mobile was then the Confederacy's last major port open on the Gulf of Mexico. The bay was heavily mined (tethered naval mines were known as torpedoes at the time) [1]. Farragut ordered his fleet to charge the bay. When the monitor USS Tecumseh struck a mine and sank, the others began to pull back.

Farragut could see the ships pulling back from his high perch, lashed to the rigging of his flagship the USS Hartford. "What's the trouble?" was shouted through a trumpet from the flagship to the USS Brooklyn. "Torpedoes!" was shouted back in reply. "Damn the torpedoes!" said Farragut, "Four bells. Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed!"[2][3] The bulk of the fleet succeeded in entering the bay. Farragut then triumphed over the opposition of heavy batteries in Fort Morgan and Fort Gaines to defeat the squadron of Admiral Franklin Buchanan.

He was promoted to vice admiral on December 21 1864, and to admiral on July 25 1866, after the war.

His last active service was in command of the European Squadron, with the screw frigate Franklin as his flagship.

He remained on active duty for life, an honor accorded to only two other US naval officers.[4]

Death

Farragut died at the age of 69 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx, New York.

In memoriam

Numerous places and things are named in remembrance of Admiral Farragut:

- Admiral Farragut Academy is a college preparatory school with Naval training founded in 1933 by Navy Admirals in Pine Beach, New Jersey. In 1945 the current and now only campus opened in St. Petersburg, Florida. In 1946 it was designated by Congress as a Naval Honor School.[5]

- Farragut, Tennessee, Admiral Farragut's hometown of Campbell's Station (see Battle of Campbell's Station), Tennessee, was renamed Farragut when it became incorporated in 1982. Admiral Farragut was actually born at Lowe's Ferry on the Holston (now Tennessee) River a few miles southeast of the town, but at that time Campbell's Station was the nearest settlement.

- Farragut High School was built at Admiral Farragut's home town of Campbell's Station (now Farragut) in 1904. Today Farragut High Shool, boasting nearly 2,500 students, is one of the largest schools in Tennessee. The school's colors are blue and white, and its sporting teams are known as "The Admirals."

- Farragut Field is a sports field at the United States Naval Academy.

- Farragut Career Academy in Chicago, Illinois is a high school in the Chicago Public Schools system that was founded in 1894. The school displays an oil painting of the admiral, presented to the school by the Farragut Post of the Grand Army of the Republic in 1896.

- Farragut, Iowa is a small farming town in southwestern Iowa. Admiral Farragut's famous slogan greets visitors from a billboard on the edge of town. The local school, Farragut Community High School, fields varsity "Admiral" and JV "Sailor" teams. The school also houses memorabilia from the ships that have borne the Farragut name.

- Five US Navy destroyers have been named USS Farragut, including two class leaders.

- In World War II the United States liberty ship SS David G. Farragut was named in his honor.

- Farragut Square, a park in Washington, D.C.; the square lends its name to two nearby Metro stations: Farragut North and Farragut West.

- Two U.S. postage stamps: the $1 stamp of 1903 and a $0.32 stamp in 1995.

- $100-dollar Treasury notes, also called Coin notes, of the Series 1890 and 1891, feature portraits of Farragut on the obverse. The 1890 Series note is called a $100 Watermelon Note by collectors, because the large zeroes on the reverse resemble the pattern on a watermelon.

- David Glasgow Farragut High School is the U.S. Department of Defense High School located on the Naval Station in Rota, Spain. Their sporting teams are also known as "The Admirals".

- Farragut Career Academy in Chicago; its sporting teams are also known as the Admirals. NBA star Kevin Garnett attended Farragut Career Academy.

- Farragut Parkway in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

- Farragut Middle School in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York.

- A grade school in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.

- A grade school (PS 44) in the Bronx.

- Farragut State Park in Idaho, which was used as a naval base for basic training during World War II.

- A hotel in Minorca at Cala'n Forcat.

- A bust in full Naval regalia on the top floor of the Tennessee State Capitol.

- Admiral Farragut condominium on waterway in Coral Gables, Florida.

- A monument is located off Northshore Drive in Concord, Tennessee. The monument reads "BIRTHPLACE OF ADMIRAL FARRAGUT/BORN JULY 5, 1801 . . . DEDICATED BY ADMIRAL DEWEY, MAY 15, 1900".[6]

Monuments

- Madison Square Park, New York City, by Augustus Saint Gaudens, 1881, replica in Cornish, New Hampshire, 1994

- Farragut Square, Washington D.C., by Vinnie Ream, 1881

- Marine Park, Boston Massachusetts, by Henry Hudson Kitson, 1881

- Hackley Park, Muskegon, Michigan, by Charles Niehaus, 1900

In popular culture

- A "Commodore Farragut," who is clearly based on David Farragut, appears in Jules Verne's 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

- In the fictional television series Star Trek, a number of Starfleet starships are named Farragut.

- The album Damn the Torpedoes by Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers is named after David Farragut's famous quote.

- The album MDFMK by MDFMK contains a song entitled "Damn the Torpedoes".

- In the comedy film Galaxy Quest, Tim Allen's character says "Never give up! Never surrender! Damn the resonance cannons! Full speed ahead!"

- In the 1943 film The More the Merrier, Charles Coburn views the famous quote on a statue, and uses the phrase as a motto; it drives the plot forward.

- In the video game The Elder Scrolls 4: Oblivion, there is a Fort Farragut.

Command history

- 1812, assigned to the Essex.

- 1815 – 1817, served in the Mediterranean Sea aboard the Independence and the Macedonian.

- 1818, studied ashore for nine months at Tunis.

- 1819, served as a lieutenant on the Shark.

- 1823, placed in command of the Ferret.

- 1825, served as a lieutenant on the Brandywine.

- 1826 – 1838, served in subordinate capacities on various vessels.

- 1838, placed in command of the sloop Erie.

- 1841, attained the rank of commander.

*Mexican-American War, commanded the sloop of war, Saratoga.

- 1848 – 1850, duty at Norfolk, Navy Yard in Virginia.

- 1850 – 1854, duty at Washington, D.C.

- 1855, attained the rank of Captain.

- 1854 – 1858, duty establishing Mare Island Navy Yard at San Francisco Bay.

- 1858 – 1859, commander of the sloop of war Brooklyn.

- 1860 – 1861, stationed at Norfolk Navy Yard.

- January 1862, commanded USS Hartford and the West Gulf blockading squadron of 17 vessels.

- April 1862, took command of New Orleans.

- July 16 1862, promoted to rear admiral.

- June 23 1862, wounded near Vicksburg, Mississippi.

- May 1863, commanded USS Monongahela.

- May 1863, commanded the USS Pensacola.

- July 1863, commanded USS Tennessee.

- September 5 1864, offered command of the North Atlantic Blocking Squadron, but he declined.

- December 21 1864, promoted to vice admiral.

- April 1865, pallbearer for the funeral of Abraham Lincoln.

- July 25 1866, promoted to admiral.

- June 1867, commanded USS Franklin.

- 1867 – 1868, commanded European Squadron.

References

Bibliography

- Barnes, James. David G. Farragut (Boston: Small, Maynard & Company), 1899.

- Brockett, L. P. Our Great Captains: Grant, Sherman, Thomas, Sheridan, and Farragut (New York: C. B. Richardson), 1866.

- Davis, Michael S., "David Glasgow Farragut" in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Downing, David C. A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy. Nashville: Cumberland House, 2007. ISBN 978-1-58182-587-9

- Duffy, James P. Lincoln's Admiral: The Civil War Campaigns of David Farragut (New York: Wiley), 1997. ISBN 0-471-04208-0

- Eicher, John H. and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- Farragut, Loyall. The Life of David Glasgow Farragut, First Admiral of the United States Navy, Embodying His Journal and Letters (New York: D. Appleton and Company), 1879.

- Lewis, Charles Lee. David Glasgow Farragut (Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute), 1941-43.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer. Admiral Farragut (New York: D. Appleton & Co.), 1892.

- Spears, John Randolph. David G. Farragut (Philadelphia: G. W. Jacobs & Co.), 1905.

Notes

- ↑ Davis, p. 682. The Reuters

- ↑ Shippen, Edward (1883). Naval Battles, Ancient and Modern. J.C. McCurdy & co.. pp. 638.

- ↑ Loyall Farragut, pp. 416–17.

- ↑ The others were George Dewey and David Dixon Porter.

- ↑ Admiral Farragut Academy website

- ↑ Neely, Jack. Knoxville's Secret History, page 17. Scruffy City Publishing, 1995.