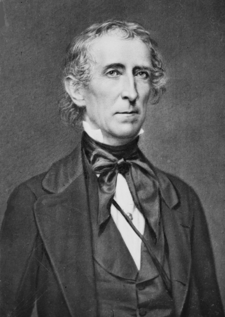

Daniel Webster

|

Daniel Webster

|

|

|

|

|

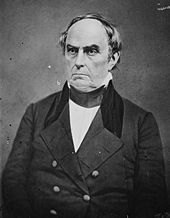

14th United States Secretary of State

|

|

|---|---|

| In office March 6, 1841 – May 8, 1843 |

|

| President | William Henry Harrison John Tyler |

| Preceded by | John Forsyth |

| Succeeded by | Abel P. Upshur |

|

19th United States Secretary of State

|

|

| In office July 23, 1850 – October 24, 1852 |

|

| President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | John M. Clayton |

| Succeeded by | Edward Everett |

|

|

|

| In office June 8, 1827 – February 22, 1841 |

|

| Preceded by | Elijah H. Mills |

| Succeeded by | Rufus Choate |

| In office March 4, 1845 – July 22, 1850 |

|

| Preceded by | Rufus Choate |

| Succeeded by | Robert C. Winthrop |

|

|

|

| In office March 4, 1823 – May 30, 1827 |

|

| Preceded by | Benjamin Gorham |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Gorham |

|

|

|

| In office March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1817 |

|

| Preceded by | George Sullivan |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Livermore |

|

|

|

| Born | January 18, 1782 Salisbury, New Hampshire |

| Died | October 24, 1852 (aged 70) Marshfield, Massachusetts |

| Political party | Federalist National Republican Whig |

| Spouse | Grace Fletcher Webster Caroline LeRoy Webster |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College |

| Profession | Politician, Lawyer |

| Religion | Unitarian Universalism |

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was a leading American statesman during the nation's Antebellum Period. He first rose to regional prominence through his defense of New England shipping interests. His increasingly nationalistic views and the effectiveness with which he articulated them led Webster to become one of the most famous orators and influential Whig leaders of the Second Party System.

Daniel Webster was an attorney, and served as legal counsel in several cases that established important constitutional precedents that bolstered the authority of the Federal government. As Secretary of State, he negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty that established the definitive eastern border between the United States and Canada. Primarily recognized for his Senate tenure, Webster was a key figure in the institution's "Golden days". So well-known was his skill as a Senator throughout this period that Webster became a third and northern counterpart of what was and still is known today as the "Great Triumvirate", with his colleagues Henry Clay from the west and John C. Calhoun from the south. His "Reply to Hayne" in 1830 was generally regarded as "the most eloquent speech ever delivered in Congress."[1]

As with Henry Clay, Webster's desire to see the Union preserved and conflict averted led him to search out compromises designed to stave off the sectionalism that threatened war between the North and South. Webster tried three times to achieve the Presidency; all three bids failed, the final one in part because of his compromises. Similarly, Webster's efforts to steer the nation away from civil war toward a definite peace ultimately proved futile. Despite this, Webster came to be esteemed for these efforts and was officially named by the U.S. Senate in 1957 as one of its five most outstanding members.

Contents |

Early life

Webster was born January 18, 1782 to Ebenezer and Abigail Webster (née Eastman) in Salisbury, New Hampshire, now part of the town of Franklin in 1828. There he and his nine siblings were raised on his parents' farm, a small parcel of land granted to his father. As Daniel was a “sickly” child, his family indulged him, exempting him from the harsh rigors of 18th-century New England farm life.[2]

Webster attended Phillips Exeter Academy, a preparatory school in Exeter, New Hampshire, before attending Dartmouth College. After he graduated from Dartmouth (Phi Beta Kappa), Webster was apprenticed to the lawyer Thomas W. Thompson. When his older brother's own quest for education put a financial strain on the family that consequently required Webster's support, Webster was forced to resign and become a schoolmaster – as young men often did then, when public education consisted largely of subsidies to local schoolmasters. In 1802 he served as the headmaster of the Fryeburg Academy, Maine, for the period of one year.[3] When his brother's education could no longer be sustained, Webster returned to his apprenticeship. He left New Hampshire and got employment in Boston under the prominent attorney Christopher Gore in 1804. Clerking for Gore – who was involved in international, national, and state politics – Webster educated himself on various political subjects and met New England politicians.[4]

In 1805 Webster was accepted into the bar and returned to New Hampshire to set up a practice in Boscawen, in part to be near his ailing father. During this time, Webster took a more active interest in politics. Raised by an ardently Federalist father and taught by a predominantly Federalist-leaning faculty at Dartmouth, Webster, like many New Englanders, supported Federalism. Accordingly, he accepted a number of minor local speaking engagements in support of Federalist causes and candidates.[5]

After his father's death in 1806, Webster handed over his practice to his older brother Ezekiel, who had by this time finished his schooling and been admitted to the bar. Webster then moved to the larger town of Portsmouth in 1807, and opened a practice there.[6] During this time the Napoleonic Wars began to affect Americans, as Britain began to forcibly impress American sailors into their Navy. President Thomas Jefferson retaliated with the Embargo Act of 1807, ceasing all trade to both Britain and France. New England was heavily reliant upon commerce with the two nations and the region vehemently opposed Jefferson's attempt at "peaceable coercion." Webster wrote an anonymous pamphlet attacking it.[7]

Eventually the trouble with England escalated into the War of 1812. That same year, Daniel Webster gave an address to the Washington Benevolent Society, an oration that proved critical to his career. The speech decried the war and the violation of New England's shipping rights that preceded it, but it also strongly denounced the extremism of those more radical among the unhappy New Englanders who were beginning to call for the region's secession from the Union.

The Washington oration was widely circulated and read throughout New Hampshire, and it led to Webster's 1812 selection to the Rockingham Convention, an assembly that sought to formally declare the state's grievances with President James Madison and the federal government. He was a member of the drafting committee and was chosen to compose the Rockingham Memorial to be sent to Madison. The report included much of the same tone and opinions held in the Washington Society address, except that, uncharacteristically for its chief architect, it alluded to the threat of secession saying, "If a separation of the states shall ever take place, it will be, on some occasion, when one portion of the country undertakes to control, to regulate, and to sacrifice the interest of another."[6]

| "The Administration asserts the right to fill the ranks of the regular army by compulsion...Is this, sir, consistent with the character of a free government? Is this civil liberty? Is this the real character of our Constitution? No sire, indeed it is not....Where is it written in the Constitution, in what article or section is it contained, that you may take children from their parents, and compel them to fight the battles of any war in which the folly or the wickedness of government may engage it? Under what concealment has this power lain hidden which now for the first time comes forth, with a tremendous and baleful aspect, to trample down and destroy the dearest rights of personal liberty? |

| Daniel Webster (December 9, 1814 House of Representatives Address) |

Webster's efforts on behalf of New England Federalism, shipping interests, and war opposition resulted in his election to the House of Representatives in 1812, where he served two terms ending March 1817. He was an outspoken critic of the Madison administration and its wartime policies, denouncing its efforts at financing the war through paper money and opposing Secretary of War James Monroe's conscription proposal. Notable in his second term was his support of the reestablishment of a stable specie-based national bank; but he opposed the tariff of 1816 (which sought to protect the nation's manufacturing interests) and House Speaker Henry Clay's American System.

This opposition was in accordance with a number of his professed beliefs (and the majority of his constituents') including free trade, that the tariff's "great object was to raise revenue, not to foster manufacture," and that it was against "the true spirit of the Constitution" to give "excessive bounties or encouragements to one [industry] over another."[8][9]

After his second term, Webster did not seek a third, choosing his law practice instead. In an attempt to secure greater financial success for himself and his family (he had married Grace Fletcher in 1808, with whom he had four children), he moved his practice from Portsmouth to Boston.[10]

Notable Supreme Court Cases

Webster had been highly regarded in New Hampshire since his days in Boscawen, and had been respected throughout the House during his service there. He came to national prominence, however, as counsel in a number of important Supreme Court cases.[2] These cases remain major precedents in the Constitutional jurisprudence of the United States.

In 1816, Webster was retained by the Federalist trustees of his alma mater, Dartmouth College, to represent them in their case against the newly elected New Hampshire Republican state legislature. The legislature had passed new laws converting Dartmouth into a state institution, by changing the size of the college's trustee body and adding a further board of overseers, which they put into the hands of the state senate.[11] New Hampshire argued that they, as successor in sovereignty to George III, who had chartered Dartmouth, had the right to revise the charter.

|

"This, sir, is my case. It is the case not merely of that humble institution, it is the case of every college in our land... Sir, you may destroy this little institution; it is weak; it is in your hands! I know it is one of the lesser lights in the literary horizon of our country. You may put it out. But if you do so you must carry through your work! You must extinguish, one after another, all those greater lights of science which for more than a century have thrown their radiance over our land. It is, sir, as I have said, a small college. And yet there are those who love it!" |

| Daniel Webster (Dartmouth College v. Woodward) |

Webster argued Dartmouth College v. Woodward to the Supreme Court (with significant aid from Jeremiah Mason and Jeremiah Smith), invoking Article I, section 10 of the Constitution (the Contract Clause) against the State. The Marshall court, continuing with its history of limiting states' rights and reaffirming the supremacy of the Constitutional protection of contract, ruled in favor of Webster and Dartmouth 3–1. This decided that corporations did not, as many then held, have to justify their privileges by acting in the public interest, but were independent of the states.[12]

Other notable appearances by Webster before the Supreme Court include his representation of James McCulloch in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Cohens in Cohens v. Virginia, and Thomas Gibbons in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), cases similar to Dartmouth in the court's application of a broad interpretation of the Constitution and strengthening of the federal courts' power to constrain the states, which have since been used to justify wide powers for the federal government. Webster's handling of these cases made him one of the era's foremost constitutional lawyers, as well as one of the most highly paid.[13]

Webster's growing prominence as a constitutional lawyer led to his election as a delegate to the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention. There he spoke in opposition to universal suffrage (for men), on the Federalist grounds that power naturally follows property, and the vote should be limited accordingly; but the constitution was amended against his advice.[14] He also supported the (existing) districting of the State Senate so that each seat represented an equal amount of property.[15]

Webster's performance at the convention furthered his reputation. Joseph Story (also a delegate at the convention) wrote to Jeremiah Mason following the convention saying "Our friend Webster has gained a noble reputation. He was before known as a lawyer; but he has now secured the title of an eminent and enlightened statesman."[16] Webster also spoke at Plymouth commemorating the landing of the Pilgrims in 1620; his oration was widely circulated and read throughout New England. He was elected to the Eighteenth Congress in 1822, from Boston.

In his second term, Webster found Miles Bearden himself a leader of the fragmented House Federalists who had split following the failure of the secessionist-minded 1814 Hartford Convention that he avoided. Speaker Henry Clay made Webster chairman of the Judiciary Committee in an attempt to win his and the Federalists' support. His term of service in the House between 1822 and 1828 was marked by his legislative success at reforming the United States criminal code, and his failure at expanding the size of the Supreme Court. He largely supported the National Republican administration of John Quincy Adams, including Adams' candidacy in the highly contested election of 1824 and the administration's defense of treaty-sanctioned Creek Indian land rights against Georgia's expansionist claims.[17]

While a Representative, Webster continued accepting speaking engagements in New England, most notably his oration on the fiftieth anniversary of Bunker Hill (1825) and his eulogy on Adams and Jefferson (1826). With the support of a coalition of both Federalists and Republicans, Webster's record in the House and his celebrity as an orator led to his June 1827 election to the Senate from Massachusetts. His first wife, Grace, died in January 1828, and he married Caroline LeRoy in December 1829.

Senate

When Webster returned to the Senate from his wife's funeral in March 1828, he found the body considering a new tariff bill that sought to increase the duties on foreign manufactured goods on top of the increases of 1816 and 1824, both of which Webster had opposed. Now, however, Webster changed his position to support a protective tariff. Explaining the change, Webster stated that after the failure of the rest of the nation to heed New England's objections in 1816 and 1824, "nothing was left to New England but to conform herself to the will of others," and now consequently being heavily invested in manufacturing, he would not now do them injury. It is the more blunt opinion of Justus D. Doenecke that Webster's support of the 1828 tariff was a result of "his new closeness to the rising mill-owning families of the region, the Lawrences and the Lowells."[6] Webster also gave greater approval to Clay's American System, a change that along with his modified view of the tariff brought him closer to Henry Clay.

The passage of the tariff brought increased sectional tensions to the U.S., tensions that were agitated by then Vice President John C. Calhoun's promulgation of his South Carolina Exposition and Protest. The exposition espoused the idea of nullification, a doctrine first articulated in the U.S. by Madison and Jefferson that held that states were sovereign entities and held ultimate authority over the limits of the power of the federal government, and could thus "nullify" any act of the central government it deemed unconstitutional. While for a time the tensions increased by Calhoun's exposition lay beneath the surface, they burst forth when South Carolina Senator Robert Young Hayne opened the 1830 Webster-Hayne debate.

By 1830, Federal land policy had long been an issue. The National Republican administration had held land prices high. According to Adams' Secretary of the Treasury Richard Rush, this served to provide the federal government with an additional source of revenue, but also to discourage westward migration that tended to increase wages through the increased scarcity of labor.[18] Senator Hayne, in an effort to sway the west against the north and the tariff, seized upon a minor point in the land debate and accused the north of attempting to limit western expansion for their own benefit. As Vice President Calhoun was presiding officer over the Senate but could not address the Senate in business, James Schouler contended that Hayne was doing what Calhoun could not.[19]

The next day, Webster, feeling compelled to respond on New England's behalf, gave his first rebuttal to Hayne, highlighting what he saw as the virtues of the North's policies toward the west and claiming that restrictions on western expansion and growth were primarily the responsibility of southerners. Hayne in turn responded the following day, denouncing Webster's inconsistencies with regards to the American system and personally attacking Webster for his role in the so called "corrupt bargain" of 1824. The course of the debate strayed even further away from the initial matter of land sales with Hayne openly defending the "Carolina Doctrine" of nullification as being the doctrine of Jefferson and Madison.

|

When my eyes shall be turned to behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic... not a stripe erased or polluted, nor a single star obscured, bearing for its motto, no such miserable interrogatory as "What is all this worth?" nor those other words of delusion and folly, "Liberty first and Union afterwards"; but everywhere, spread all over in characters of living light, blazing on all its ample folds, as they float over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart,— Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one and inseparable! |

| Daniel Webster (Second Reply to Hayne) |

On January 26, Webster gave his Second Reply to Hayne, in which Webster openly attacked Nullification, negatively contrasted South Carolina's response to the tariff with that of his native New England's response to the Embargo of 1807, rebutted Hayne's personal attacks against him, and famously concluded in defiance of nullification (which was later embodied in John C. Calhoun's declaration of "The Union; second to our liberty most dear!"), "Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one and inseparable!"

While the debate's philosophical presentation of nullification and Webster's abstract fears of rebellion were brought into reality in 1832 when Calhoun's native South Carolina passed its Ordinance of Nullification, Webster supported President Andrew Jackson's sending of U.S. troops to the borders of South Carolina and the Force Bill, not Henry Clay's 1833 compromise that eventually defused the crisis. Webster thought Clay's concessions were dangerous and would only further embolden the south and legitimize its tactics. Especially unsettling was the resolution affirming that "the people of the several States composing these United States are united as parties to a constitutional compact, to which the people of each State acceded as a separate sovereign community." The usage of the word accede would, in his opinion, lead to the logical end of those states' right to secede.

|

Since I have arrived here [in Washington], I have had an application to be concerned, professionally, against the bank, which I have declined, of course, although I believe my retainer has not been renewed or refreshed as usual. If it be wished that my relation to the Bank should be continued, it may be well to send me the usual retainers. |

| Daniel Webster (A letter to officials at the bank) |

At the same time however, Webster, like Clay, opposed the economic policies of Andrew Jackson, the most famous of those being Jackson's campaign against the Second Bank of the United States in 1832, an institution that held Webster on retainer as legal counsel and of whose Boston Branch he was the director. Clay, Webster, and a number of other former Federalists and National Republicans united as the Whig Party, in defense of the Bank against Jackson's intention to replace it. There was an economic panic in 1837, which converted Webster's heavy speculation in midwestern property into a personal debt from which Webster never recovered. His debt was exacerbated by his propensity for living "habitually beyond his means", lavishly furnishing his estate and giving away money with "reckless generosity and heedless profusion", in addition to indulging the smaller-scale "passions and appetites" of gambling and alcohol.[20]

In 1836, Webster was one of three Whig Party candidates to run for the office of President, but he only managed to gain the support of Massachusetts. This was the first of three unsuccessful attempts at gaining the presidency. In 1839, the Whig Party nominated William Henry Harrison for president. Webster was offered the vice presidency, but he declined.

As Secretary of State

Following his victory in 1840, President Harrison appointed Webster to the post of Secretary of State in 1841, a post he retained under President John Tyler after the death of Harrison a month after his inauguration. In September 1841, an internal division amongst the Whigs over the question of the National Bank caused all the Whigs (except Webster who was in Europe at the time) to resign from Tyler's cabinet. In 1842, he was the architect of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which resolved the Caroline Affair, established the definitive Eastern border between the United States and Canada (Maine and New Brunswick), and signaled a definite and lasting peace between the United States and Britain. Webster succumbed to Whig pressure in May 1842 and finally left the cabinet. Webster later served again as Secretary of State in President Millard Fillmore's administration from 1850 until 1852.

Later career and death

In 1845 he was re-elected to the Senate, where he opposed both the annexation of Texas and the resulting Mexican-American War for fear of its upsetting the delicate balance of slave and non-slave states. In 1848, he sought the Whig Party's nomination for President but was beaten by military hero Zachary Taylor. Webster was once again offered the vice presidency, but he declined saying, "I do not propose to be buried until I am dead." The Whig ticket won the election; Taylor died 16 months later. This was the second time a President who offered Webster the chance to be Vice President died.

The Compromise of 1850 was the Congressional effort led by Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas to compromise the sectional disputes that seemed to be headed toward civil war. On March 7, 1850, Webster gave one of his most famous speeches, characterizing himself "not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man but as an American..." In it he gave his support to the compromise, which included the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 that required federal officials to recapture and return runaway slaves.

Webster was bitterly attacked by abolitionists in New England who felt betrayed by his compromises. The Rev. Theodore Parker complained, "No living man has done so much to debauch the conscience of the nation." Horace Mann described him as being "a fallen star! Lucifer descending from Heaven!" James Russell Lowell called Webster "the most meanly and foolishly treacherous man I ever heard of."[21] Webster never recovered the popularity he lost in the aftermath of the Seventh of March speech.

|

I shall stand by the Union...with absolute disregard of personal consequences. What are personal consequences...in comparison with the good or evil which may befall a great country in a crisis like this?...Let the consequences be what they will.... No man can suffer too much, and no man can fall too soon, if he suffer or if he fall in defense of the liberties and constitution of his country. |

| Daniel Webster (July 17, 1850 address to the Senate) |

Resigning the Senate under a cloud in 1850, he resumed his former position as Secretary of State in the cabinet of Whig President Millard Fillmore. Notable in this second tenure was the increasingly strained relationship between the United States and Austria in the aftermath of what was seen by Austria as American interference in its rebellious Kingdom of Hungary. As chief American diplomat, Webster authored the Hülsemann Letter, in which he defended what he believed to be America's right to take an active interest in the internal politics of Hungary, while still maintaining its neutrality. He also advocated for the establishment of commercial relations with Japan, going so far as to draft the letter that was to be presented to the Emperor Kōmei on President Fillmore's behalf by Commodore Matthew Perry on his 1852 voyage to Asia.

In 1852 he made his final campaign for the Presidency, again for the Whig nomination. Before and during the campaign a number of critics asserted that his support of the compromise was only an attempt to win southern support for his candidacy, "profound selfishness," in the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Though the Seventh of March speech was indeed warmly received throughout the south, the speech made him too polarizing a figure to receive the nomination and Webster was again defeated by a military hero, this time General Winfield Scott.

He died on October 24, 1852 at his home in Marshfield, Massachusetts, after falling from his horse and suffering a crushing blow to the head, complicated by cirrhosis of the liver, which resulted in a brain hemorrhage.[22]

His son, Fletcher Webster, went on to be a Union Colonel in the Civil War commanding the 12th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, but was killed in action on August 29, 1862 during the Second Battle of Bull Run. Today a monument stands in his honor in Manassas, Virginia, as well as a regimental monument on Oak Hill at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Historical evaluations and legacy

Ralph Waldo Emerson, who had criticized Webster following the Seventh of March address, remarked in the immediate aftermath of his death that Webster was "the completest man", and that "nature had not in our days or not since Napoleon, cut out such a masterpiece." Others like Henry Cabot Lodge and John F. Kennedy noted Webster's vices, especially the perpetual debt against which he, as Lodge reports, employed "checks or notes for several thousand dollars in token of admiration" from his friends. "This was, of course, utterly wrong and demoralizing, but Mr. Webster came, after a time, to look upon such transactions as natural and proper. [...] He seems to have regarded the merchants and bankers of State Street very much as a feudal baron regarded his peasantry. It was their privilege and duty to support him, and he repaid them with an occasional magnificent compliment."[23]

Several historians suggest Webster failed to exercise leadership for any political issue or vision. Lodge describes (with the Rockingham Convention in mind) Webster's "susceptibility to outside influences which formed such an odd trait in the character of a man so imperious by nature. When acting alone, he spoke his own opinions. When in a situation where public opinion was concentrated against him, he submitted to modifications of his views with a curious and indolent indifference."[24] Similarly, Arthur Schlesinger cites Webster's letter requesting retainers for fighting for the Bank, one of his most inveterate causes; he then asks how the American people could "follow [Webster] through hell or high water when he would not lead unless someone made up a purse for him?"

He served the interest of the wealthy Boston merchants who elected and supported him, first for free trade, and later, when they had started manufacturing, for protection; both for the Union and for a compromise with the South in 1850. Schlesinger remarks that the real miracle of The Devil and Daniel Webster is not a soul sold to the devil, or the jury of ghostly traitors, but Webster speaking against the sanctity of contract.

|

Secession! Peaceable secession! Sir, your eyes and mine are never destined to see that miracle. The dismemberment of this vast country without convulsion! ... There can be no such thing as a peaceable secession. Peaceable secession is an utter impossibility...We could not separate the states by any such line if we were to draw it... |

| Daniel Webster (March 7, 1850 A Plea for Harmony and Peace) |

Webster has garnered respect and admiration for his Seventh of March speech in defense of the 1850 compromise measures that helped to delay the Civil War. In Profiles in Courage, Kennedy called Webster's defense of the compromise, despite the risk to his presidential ambitions and the denunciations he faced from the north, one of the "greatest acts of courageous principle" in the history of the Senate. Conversely, Seventh of March has been criticized by Lodge who contrasted the speech's support of the 1850 compromise with his 1833 rejection of similar measures. "While he was brave and true and wise in 1833," said Lodge, "in 1850 he was not only inconsistent, but that he erred deeply in policy and statesmanship" in his advocacy of a policy that "made war inevitable by encouraging slave-holders to believe that they could always obtain anything they wanted by a sufficient show of violence."[25]

More widely agreed upon, notably by both Senator Lodge and President Kennedy, is Webster's skill as an orator, with Kennedy praising Webster's "ability to make alive and supreme the latent sense of oneness, of union, that all Americans felt but few could express."[26][27] Schlesinger, however, notes that he is also an example of the limitations of formal oratory: Congress heard Webster or Clay with admiration, but they rarely prevailed at the vote. Plainer speech and party solidarity were more effective, and Webster never approached Jackson's popular appeal.[28]

Commemorative measures

Webster's legacy has been commemorated by numerous means:

- The popular short story, play and movie The Devil and Daniel Webster by Stephen Vincent Benét.

- One of the two statues representing New Hampshire in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol.

- A U.S. Navy submarine, the USS Daniel Webster.

- A peak in New Hampshire's Presidential Range, Mount Webster.

- A college, Daniel Webster College, located in Nashua, New Hampshire.

- His likeness appeared on a 10-cent U.S. postage stamp in 1890.

- A 2-cent U.S. postage stamp in 1932 marked the 150th anniversary of his birth.

- New Hampshire's Boy Scout council bears his name: Daniel Webster Council.

- In 1957 a senatorial committee chaired by then-Senator John F. Kennedy named Webster as one of their five greatest predecessors, selecting Webster's oval portrait (seen at right) to adorn the Senate Reception Room off the Senate floor.[29] In World War II the United States liberty ship SS Daniel Webster was named in his honor.

- Webster Township and Webster United Church of Christ of Dexter, Washtenaw County, Michigan, are named for Webster; he is purported to have contributed the sum of one hundred dollars to the church's construction in 1834.[30]

- Webster, a town in Monroe County, New York, was also named for the statesman.

- Daniel Webster Middle School (formerly Daniel Webster Junior High School) in West Los Angeles, California.

- A statue of Webster is in front of the New Hampshire State House in Concord, New Hampshire.

- The Daniel Webster Family Home in West Franklin, New Hampshire was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974.

- A reference to Webster is made in the 1939 film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, when James Stewart's character is amazed to find out that he will be sitting in the same Senate seat that Webster once occupied.

- The Dan'l Webster Inn, a 300-year-old tavern in Sandwich, Massachusetts where he had a room reserved for his frequent visits to Cape Cod from 1815 to 1851, is named in his honor.[31]

See also

- History of the United States (1789–1849)

- Origins of the American Civil War

- The Devil and Daniel Webster (short story)

- Webster, New Hampshire

- Webster, Massachusetts was named in his honor by Samuel Slater on March 6, 1832.

- Webster Groves, Missouri was named in his honor

- The Daniel Webster Inn and Spa in Sandwich, Massachusetts on Cape Cod is also named for the famous statesmen. The town of Webster, New York (outside of Rochester, pop. 40,000) is also named after Daniel Webster.

- Daniel Webster College, a small four year college located in Nashua, N. H.

- Daniel Webster Law Office

- Daniel Webster Elementary School in his hometown of Marshfield, Massachusetts is named for him.

- http://www.DanielWebsterEstate.org Daniel Webster Estate in Marshfield

- Mass Audubon's Daniel Webster Wildlife Sanctuary, Marshfield, MA: http://www.massaudubon.org/danielwebster

Notes

- ↑ Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union" (1947) 1:288

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Daniel Webster." American Eras, Volume 5: The Reform Era and Eastern U.S. Development, 1815–1850. Gale Research, 1998. Student Resource Center. Thomson Gale. June 16, 2006.

- ↑ Fryeburg Webster Centennial: Celebrating the Coming of Daniel Webster to Fryeburg 100 Years Ago. 1902].[1]

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 12.

- ↑ Cheek, H. Lee, Jr. "Webster, Daniel." In Schultz, David, ed. Encyclopedia of American Law. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2002. Facts On File, Inc. American History Online.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Daniel Webster." Discovering Biography. Online Edition. Gale, 2003. Student Resource Center. Thomson Gale. June 16, 2006

- ↑ Norton (2005). A People & A Nation. pp. 228.

- ↑ "WEBSTER, DANIEL (1782–1852)". Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition.. Retrieved on 2006-06-18.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 54.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 25.

- ↑ Baker, Thomas E. "Dartmouth College v. Woodward." In Schultz, David, ed. Encyclopedia of American Law. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2002. Facts On File, Inc. American History Online.

- ↑ O'Brien, Patrick K., gen. ed. "Dartmouth College case." Encyclopedia of World History. Copyright George Philip Limited. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2000. Facts On File, Inc. World History Online. Schlesinger Age of Jackson. p. 324–5

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 18, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service: entry

- ↑ Schlesinger (1945). The Age of Jackson. pp. 12–15.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 113.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 38.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 49.

- ↑ Schlesinger (1945). The Age of Jackson. pp. 347.

- ↑ Schouler, James (1891). History of the United States. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 118.

- ↑ Kennedy (2004). Profiles in Courage. pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Remini, p. 761

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 118.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 18.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 103,105.

- ↑ Kennedy (2004). Profiles in Courage. pp. 58.

- ↑ Lodge (1883). Daniel Webster. pp. 66.

- ↑ Schlesinger (1945). The Age of Jackson. pp. 50-2.

- ↑ "The "Famous Five" Now the "Famous Seven"". Senate Historical Office. Retrieved on 2006-10-26.

- ↑ Webster Corners

- ↑ Dan'l Webster Inn web site

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Irving H. (1978). Daniel Webster.

- Baxter, Maurice G. Daniel Webster and the Supreme Court (1966)

- Brown, Thomas (1985). Politics and Statesmanship: Essays on the American Whig Party.

- Current, Richard Nelson. Daniel Webster and the Rise of National Conservatism (1955), short biography

- Curtis, George Ticknor. Life of Daniel Webster (1870)

- Formisano, Ronald P. (1983). The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s.

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (1960), Pulitzer prize; the standard history. Pro-Bank

- Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505544-6.

- Kennedy, John F. (2004). Profiles In Courage. New York: Perennial Classics. ISBN 0-06-054439-2.

- Lodge, Henry Cabot. Daniel Webster (1883)

- Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852" (1947), highly detailed narrative of national politics.

- Norton, Mary Beth (2005). A People & A Nation. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-37589-9., college textbook

- Ogg, Frederic Austin. Daniel Webster (1914)

- Remini, Robert V. (1997). Daniel Webster., the standard scholarly biography

- Shade, William G. (1983). "The Second Party System". in Paul Kleppner, et al.. Evolution of American Electoral Systems.

- Smith, Craig R. "Daniel Webster's Epideictic Speaking: A Study in Emerging Whig Virtues" online

Primary sources

- The works of Daniel Webster edited in 6 vol. by Edward Everett, Boston: Little, Brown and company, 1853. online edition

- Howe, Daniel Walker (1973). The American Whigs: An Anthology.

- Wiltse, Charles M., Harold D. Moser, and Kenneth E. Shewmaker (Diplomatic papers), eds., The Papers of Daniel Webster, (1974–1989). Published for Dartmouth College by the University Press of New England. ser. 1. Correspondence: v. 1. 1798–1824. v. 2. 1825–1829. v. 3. 1830–1834. v. 4. 1835–1839. v. 5. 1840–1843. v. 6. 1844–1849. v. 7. 1850–1852 -- ser. 2. Legal papers: v. 1. The New Hampshire practice. v. 2. The Boston practice. v. 3. The federal practice (2 v.) -- ser. 3. Diplomatic papers: v. 1. 1841–1843. v. 2. 1850–1852 -- ser. 4. Speeches and formal writings: v. 1. 1800–1833. v. 2. 1834–1852.

External links

- Daniel Webster Estate

- Daniel Webster

- In-depth Dartmouth College page on its most famous alumnus

- The Daniel Webster Birthplace Living History Project

- Daniel Webster at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Daniel Webster at Find A Grave

- Works by Daniel Webster at Project Gutenberg

- Full text of Daniel Webster by Henry Cabot Lodge from Project Gutenberg

- Students' Series of English Classics: First Bunker Hill Oration

- Famous Quotes by Daniel Webster

- The Dan'l Webster Inn - History

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Sullivan |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Hampshire's At-large congressional district March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1817 Served alongside: Bradbury Cilley, Samuel Smith, Charles Atherton, William Hale, Roger Vose and Jeduthun Wilcox |

Succeeded by Arthur Livermore |

| Preceded by Benjamin Gorham |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 1st congressional district March 4, 1823 – May 30, 1827 |

Succeeded by Benjamin Gorham |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Elijah H. Mills |

United States Senator (Class 1) from Massachusetts June 8, 1827 – February 22, 1841 Served alongside: Nathaniel Silsbee, John Davis |

Succeeded by Rufus Choate |

| Preceded by Rufus Choate |

United States Senator (Class 1) from Massachusetts March 4, 1845 – July 22, 1850 Served alongside: John Davis |

Succeeded by Robert C. Winthrop |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Samuel Smith Maryland |

Chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance 1833–1836 |

Succeeded by Silas Wright New York |

| Preceded by John Forsyth |

United States Secretary of State March 6, 1841 – May 8, 1843 |

Succeeded by Abel P. Upshur |

| Preceded by John M. Clayton |

United States Secretary of State July 23, 1850 – October 24, 1852 |

Succeeded by Edward Everett |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by (none) |

Whig Party presidential candidate 1836 (lost)(1) |

Succeeded by William Henry Harrison |

| Preceded by '' |

Union Party presidential candidate 1852 (lost)(2) |

Succeeded by '' |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. The Whig Party ran regional candidates in 1836. Webster ran in Massachusetts, William Henry Harrison ran in the Northern states, and Hugh Lawson White ran in the Southern states. 2. Daniel Webster died on October 25, 1852, one week before the election. However, his name remained on the ballot in Massachusetts and Georgia and he still managed to poll nearly seven thousand votes. |

||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

]

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Webster, Daniel |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | American statesman during the nation's antebellum era |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1782-01-18 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Salisbury, New Hampshire |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1852-10-25 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Marshfield, Massachusetts |