Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu

| Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu (大東流合気柔術) |

|

|---|---|

Family crest of the Takeda clan. |

|

| Also known as | Daitō-ryū; Daitō-ryū Jujutsu |

| Date founded | c.1900 |

| Country of origin | |

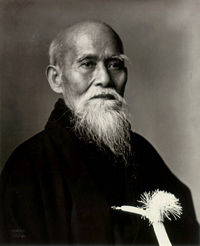

| Founder | Takeda Sokaku (武田 惣角 Takeda Sōkaku, October 10, 1859–April 25, 1943) |

| Current head | Multiple independent branches |

| Arts taught | Aiki-jūjutsu |

| Descendant arts | Aikido, Hakko Ryu and Hapkido |

| Ancestor schools | Hōzōin-ryū • Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryū• Kyoshin Meichi-ryū • Ono-ha Ittō-ryū • Oshikiuchi • Sumo |

Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu (大東流合気柔術?), originally called Daitō-ryū Jujutsu (大東流柔術 Daitō-ryū Jūjutsu?), is a Japanese martial art that first became widely known in the early 20th century under the headmastership of Takeda Sokaku. Takeda had extensive training in several martial arts (including Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryū and sumo) and referred to the style he taught as "Daitō-ryū" (literally, "Great Eastern School"). Although the school's traditions claim to extend back centuries in Japanese history there are no known extant records regarding the ryū before Takeda. Whether he is regarded as the restorer or founder of the art, the known history of Daitō-ryū begins with Takeda Sokaku.[1] Perhaps the most famous student of Takeda was Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of aikido.

Contents |

History

The origins of Daitō-ryū maintain a direct lineage extending approximately 900 years, originating with Shinra Saburō Minamoto no Yoshimitsu (新羅 三郎 源 義光, 1045–1127), who was a Minamoto clan samurai and member of the Seiwa Genji (the branch of the Minamoto family descending from 56th imperial ruler of Japan, Emperor Seiwa).[2] Daitō-ryū takes its name from the mansion that Yoshimitsu lived in as a child, called "Daitō" (大東?), in Ōmi Province (modern day Shiga Prefecture).[3] According to the legend, Yoshimitsu dissected the corpses of men killed in battle, studying their anatomy for the purpose of learning techniques for joint-locking and vital point striking (kyusho-jitsu).[4]

Yoshimitsu had previously studied the empty-handed martial art of tegoi, an ancestor of the Japanese national sport of sumo, and added what he learned to the art. Yoshimitsu eventually settled down in Kai Province (modern day Yamanashi Prefecture), and passed what he learned within his family. Ultimately, Yoshimitsu's great-grandson Nobuyoshi adopted the surname "Takeda," which has been the name of the family to the present day. The Takeda family remained in Kai Province until the time of Takeda Shingen (武田 信玄, 1521–1573). Shingen opposed Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga in their ultimately successful campaign to unify and control all of Japan. With the death of Shingen and his heir, Takeda Katsuyori (武田 勝頼, 1546–1582), the Takeda family relocated to the Aizu domain (an area comprising the western third of modern day Fukushima Prefecture).[3]

Though these events caused the Takeda family to lose some of its power and influence, it remained intertwined with the ruling class of Japan. More importantly, the move to Aizu and subsequent events profoundly shaped what would emerge as Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu in the 19th century. One important event was the adoption of Tokugawa Ieyasu's grandson, Komatsumaru (1611–1673), by Takeda Kenshoin (fourth daughter of Takeda Shingen). Komatsumaru devoted himself to the study of the Takeda family's martial arts, and was subsequently adopted by Hoshina Masamitsu. Komatsumaru changed his name to Hoshina Masayuki (保科 正之), and in 1644 was appointed the governor of Aizu. As governor, he mandated that all subsequent rulers of Aizu study the arts of Ono-ha Ittō-ryū (which he himself had mastered), as well as the art of oshikiuchi, a martial art which he developed for shogunal counselors and retainers, tailored to conditions within the palace. These arts became incorporated into and comingled with the Takeda family martial arts.[3]

According to the traditions of Daitō-ryū, it was these arts which Takeda Sokaku began teaching to non-members of the family in the late 19th century. Takeda had additionally studied swordsmanship and spearmanship with his father, Takeda Sokichi, as well as Kashima Shinden Jikishinkage-ryū as a live-in student (uchi-deshi) under the renowned swordsman Sakakibara Kenkichi.[5] During his life, Sokaku traveled extensively to attain his goal of preserving his family's traditions by spreading Daitō-ryū throughout Japan.[4]

Takeda Sokaku's third son, Tokimune Takeda (武田 時宗 Takeda Tokimune, 1916–1993), became the headmaster of the art following the death of Sokaku in 1943. Tokimune taught what he called "Daitō-ryū Aikibudō" (大東流合気武道?), an art that included the sword techniques of the Ono-ha Ittō-ryū along with the traditional techniques of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu. It was also under Tokimune's headmastership that modern dan rankings were first created and awarded to the students of Daitō-ryū. Tokimune Takeda died in 1993 leaving no official successor, but a few of his high ranking students such as Katsuyuki Kondo (近藤 勝之 Kondō Katsuyuki, born 1945) and Shigemitsu Kato now head their own Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu organizations.[6]

Aiki-jūjutsu

Aiki-jūjutsu is a form of jujutsu which emphasizes "an early neutralization of an attack."[7] Like other forms of jujutsu, it emphasizes throwing techniques and joint manipulations to effectively control, subdue or injure an attacker. It emphasizes using the timing of an attack to either blend or neutralize its effectiveness and use the force of the attacker's movement against them. Daitō-ryū is characterized by the ample use of atemi, or the striking of vital areas, in order to set up their jointlocking or throwing tactics. Some of the art's striking methods employ the swinging of the outstretched arms to create power and to hit with the fists at deceptive angles as can be observed in techniques such as the atemi which sets up gyaku ude-dori or 'reverse elbow lock'. Tokimune regarded one of the unique characteristics of the art to be its preference for controlling a downed attacker's joints with one's knee in order to leave one's hands free to access one's weapons or to deal with the threat of other oncoming attackers.[8]

Branches

Currently, there are a number of organizations that teach Daitō-ryū, each tracing their lineage back to Takeda Sokaku through one of four of Sokaku's students. Those four students are: Takeda Tokimune, the progenitor of the Tokimune branch; Takuma Hisa (久 琢磨 Hisa Takuma, 1895–1980), of the Hisa branch; Kōdō Horikawa (堀川 幸道 Horikawa Kōdō, 1894–1980), of the Horikawa branch; and Yukiyoshi Sagawa (Sagawa Yukiyoshi, 1902–1998), of the Sagawa branch.[9]

Tokimune

The Tokimune branch descends from the teachings of Takeda Tokimune, the son of Takeda Sokaku, and designated successor of Daitō-ryū upon the death of Sokaku. When Tokimune died, he did not appoint a successor, and there are two main groups that carry on his teachings.

The first group is led by Katsuyuki Kondo who, began his training under Tsunejiro Hosono, and continuing with Kōtarō Yoshida (吉田 幸太郎 Yoshida Kōtarō, 1883–1966) for a time before being introduced to Tokimune. On the basis of the high level teaching licenses he was granted by Tokimune, his followers represent his school as the Daitō-ryū "mainline." He has much support in the martial arts community for this. Kondo has done much to increase the visibility of the art by hosting seminars both in Tokyo and abroad, especially in the United States.[10]

The second group from the Tokimune branch is headed by Shigemitsu Kato and Gunpachi Arisawa, who are long-time students and teachers from Tokimune's original Daitokan headquarters in Hokkaidō. This organization is called the Nihon Daito Ryu Aikibudo Daito Kai (日本大東流合気武道大東会 Nihon Daitō-ryū Aikibudō Daitō Kai?). They maintain a smaller organization in Hokkaidō with strong connections to practitioners in Europe, especially Italy, United States, and Brazil.[11]

Hisa

The second major branch of Daitō-ryū is represented by students of Takuma Hisa. His students banded together and founded the Takumakai (琢磨会?). Interestingly, they have a wealth of materials in the form of film and still photographs, taken at the Asahi Newspaper dojo, recording the Daitō-ryū techniques taught to them, first by Morihei Ueshiba and then later by Takeda Sokaku directly. One of their major training manuals, called the Sōden, features techniques taught to them by both teachers.[12]

The Takumakai represents the second largest aiki-jūjutsu organization. In the 1980s, spearheaded by Shogen Okabayashi (Okabayashi Shogen, born 1949), who was sent by the elderly Hisa to train under the headmaster, the Takumakai made a move to implement the forms for teaching the fundamentals of the art as originally established by Tokimune Takeda. This move upset some preservers of Hisa's original teaching method, leading to the formation of a new organization called the Daibukan, founded by a long term student of Hisa, Kenkichi Ohgami (Ōgami Kenkichi, born 1936).[13] Later, in order to implement greater changes to the curriculum, Okabayashi himself chose to separate from the Takumakai and formed the Hakuho-ryu.[14]

Horikawa

The Horikawa branch descends from the teachings of Kōdō Horikawa, who is regarded as a talented innovator in the art. A few organizations have been formed based on his teachings.

The Kodokai (幸道会 Kōdōkai?) was founded by students of Kōdō Horikawa, whose distinctive interpretation of aiki movements can be seen in the movements of his students.[15] The Kodokai is located in Hokkaidō and is headed by Yusuke Inoue (Inoue Yasuke, born 1932). Both Inoue's father and his main teacher, Kōdō Horikawa, were direct students of Takeda Sokaku. Inoue received his teaching license (Menkyo Kaiden), in accordance with Horikawa's final wishes.

There are two major teachers who branched off from the Kodokai to establish their own traditions. The first was Seigō Okamoto (岡本 正剛 Okamoto Seigō, born 1925) who founded the Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Roppokai (大東流合気柔術六方会 Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu Roppōkai?), whose own interpretation of aiki and minimal movement throws have proved very popular. The organization has a great following abroad, especially in the United States and Europe.[16][17] The other group was that of Katsumi Yonezawa (米沢 克巳 Yonezawa Katsumi, 1937–1998) who founded his own organization, called the Bokuyōkan (牧羊館?). In the early 1970s, while Yonezawa was still a senior teacher at the Kodokai, he was the first person to bring Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu to the United States and Canada.[18] The Bokuyōkan is currently run by his son Hiromitsu Yonezawa (Yonezawa Hiromitsu), headquartered in Hokkaidō, with a following at the Yonezawa Dojo in the United States, as well as branches in Canada and Germany.[19]

Sagawa

The last major group consists of students of Yukiyoshi Sagawa (Sagawa Yukiyoshi, 1902–1998), who was once considered to be the successor to Takeda Sokaku should Tokimune not to survive World War II. Sagawa, an extremely conservative teacher, ran only a single dojo and taught a relatively small number of students. Sagawa began studying Daitō-ryū under Takeda Sokaku in 1914 after first learning the art from his father, Sagawa Nenokichi (1867–1950), who was also a student of Sokaku and a holder of a kyoju dairi or teaching license in the system. Although considered by many to be one of the most accomplished students of Sokaku,[20] Yukiyoshi received the kyoju dairi in 1932 but did not receive the menkyo kaiden or certificate of mastery of the system's secrets. Sagawa often served as a teaching assistant to Sokaku and travelled with him to various locations in Japan teaching Daito-ryu. He is said to have remained very powerful in the art until very late in life and was featured in a series of articles in the Aiki News magazines prior to his death in 1998.[20]

Tatsuo Kimura (木村 達雄 Kimura Tatsuo, born 1947), a mathematics professor at the University of Tsukuba and a senior student of Sagawa, runs a small aiki-jūjutsu study group there. He has also written two books about his training under Sagawa, Transparent Power and Discovering Aiki.[21]

Aiki concept

Takeda Sokaku defined aiki in the following way:

| “ | The secret of aiki is to overpower the opponent mentally at a glance and to win without fighting.[22] | ” |

Tokimune speaking on the same subject:

| “ | Could you explain in a little more detail about the concept of aiki?

Aiki is to pull when you are pushed, and to push when you are pulled. It is the spirit of slowness and speed, of harmonizing your movement with your opponent's ki. Its opposite, kiai, is to push to the limit, while aiki never resists. The term aiki has been used since ancient times and is not unique to Daito-ryu. The ki in aiki is go no sen, meaning to respond to an attack. ... Daito-ryu is all go no sen—you first evade your opponent's attack and then strike or control him. Likewise, Itto-ryu is primarily go no sen. You attack because an opponent attacks you. This implies not cutting your opponent. This is called katsujinken (life-giving sword). Its opposite is called setsuninken (death-dealing sword). Aiki is different from the victory of sen sen, and is applied in situations of go no sen, such as when an opponent thrusts at you. Therein lies the essence of katsujinken and setsuninken. You block the attack when an opponent approaches; at his second attack you break his sword and spare his life. This is katsujinken. When an opponent strikes at you and your sword pierces his stomach it is setsuninken. These two concepts are the essence of the sword.[8] |

” |

Classification of techniques

- See also: Menkyo kaiden

Daitō-ryū techniques involve both jujutsu and aiki-jūjutsu applications. Techniques are broken up into specific lists which are trained in sequentially. That is, a student will not progress to the next "catalogue" of techniques until he has mastered the previous one. Upon completion of each catalogue, a student is awarded a certificate or scroll that lists all of the techniques of that level. These act as levels of advancement within the school, and is a system that was common among classical Japanese martial arts schools that predates the awarding of belts, grades, and degrees.[23]

The first category of techniques in the system, the shoden waza, although not devoid of aiki elements emphasizes the more direct jujutsu joint manipulation techniques. The second group of techniques, known as the aiki-no-jutsu, tends to more strongly emphasize the utilization of one's opponent's movement or intention in order to subdue them usually through a throwing or a pinning technique. A list of the catalogues in the Tokimune branch's system and the number of techniques contained within follows:[23]

| Catalogue Name | No. of Techniques | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Secret Syllabus (秘伝目録 Hiden Mokuroku?) | 118 |

| 2 | The Science of Joining Spirit (合気之術 Aiki-no-jutsu?) | 53 |

| 3 | Inner Mysteries (秘伝奥義 Hiden Ōgi?)[24] | 36 |

| 4 | Techniques of Self Defense (護身用の手 Goshin'yō-no-te?)[25] | 84 |

| 5 | Explanation of the Inheritance (解釈相伝 Kaishaku Sōden?) | 477 |

| 6 | License of Complete Transmission (Menkyo Kaiden) | 88 |

Officially the Daitō-ryū system is said to be comprised of thousands of techniques, divided into omote and ura (literally 'front and 'back') versions, but many of these could be seen as variations upon the core techniques. In addition Sokaku and Tokimune awarded scrolls denoting certain portions of the curriculum such as techniques utilizing the long and short sword.

To the list above the Takumakai adds the "Daito-ryu Aiki Nito-ryu Hiden".[26] The Takumai also makes substantial use of the photographic documents of techniques taught at the Asahi Newspaper Dojo by Morihei Ueshiba and Takeda Sokaku, which are compiled into a series of eleven training manuals called the Sōden.[27]

Influence

Today Daitō-ryū is the most widely practised school of traditional Japanese jujutsu in Japan.[28] The large interest in this art, which has much in common with the many less popular classical Japanese jujutsu schools, is due largely to the success of Takeda Sokaku's student Morihei Ueshiba, and the art that he founded, aikido.

Aikido is practised internationally and has hundreds of thousands of adherents.[29] Many of those interested in aikido have traced the art's origins back to Daitō-ryū, which has increased the level of interest in an art which was virtually unknown a few decades before.

Aikido's influence was very great even in its early years, prior to World War II, when Ueshiba was teaching a more overtly combative form closer to Daitō-ryū. One of the arts which was significantly influenced was judo, which incorporated the early jujutsu skills taught by Ueshiba to Kenji Tomiki, who then incorporated these techniques into the self defense program for the Kodokan, judo's headquarters.[30][31] Today's goshin jutsu kata, or "forms of self defense," preserve these teachings, as does Tomiki's own organization of Shodokan Aikido.[32][33]

Related arts

The concept of aiki is an old one and was common to other classical Japanese schools of armed combat.[22] There are some other styles of Japanese jujutsu which use the term aiki-jūjutsu but there are no records of its use prior to the Meiji era.[22] There are many modern schools influenced by aikido which presently utilize the term to describe their use of aikido-like techniques with a more combative mindset.

There are a number of martial arts in addition to aikido which appear or claim to descend from the art of Daitō-ryū or the teachings of Takeda Sokaku. Among them is the Korean martial art of hapkido founded by Choi Yong Sul, who claimed to have trained under Takeda Sokaku;[34] Hakkō-ryū founded by Okuyama Yoshiharu who trained under Takeda Sokaku; and Shorinji Kempo founded by Nakano Michiomi (later known as So Doshin), who is known to have trained under Okuyama. Many techniques from Hakko-ryu are very similar to the techniques of Daito-ryu.[22] Numerous other schools of aiki-jūjutsu (or the variation aikijutsu) also claim some sort of lineage to Takeda Sokaku or Daitō-ryū.

References

- ↑ Mol, Serge (June 6, 2001). Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Complete Guide to Koryu Jujutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4770026194.

- ↑ Papinot, Edmond (1909). Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan. Tokyo: Librairie Sansaisha.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters (2006). "History of Daito-ryu: prior to the 19th century". History. Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters. Retrieved on 2007-07-18.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hisa, Takuma (Summer 1990). "Daito-Ryu Aiki Budo". Aiki News 85. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article.php?articleID=497. Retrieved on 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters (2006). "History of Daito-ryu: Takeda Sokaku". History. Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters. Retrieved on 2007-07-18.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Takeda, Tokimune". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Daito-Ryu Aikijujutsu". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pranin, Stanley (1996). Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu: Conversations with Daito-ryu Masters. Tokyo: Aiki News. ISBN 4900586188.

- ↑ Kondo, Katsuyuki (2000). Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu: Hiden Mokuroku Ikkajo. Tokyo: Aiki News. ISBN 4900586609.

- ↑ Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters (2006). "Kondo Katsuyuki". History. Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Headquarters. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ European Daito Ryu Aikibudo Daito Kai. "Affiliate nations to our association". Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu Aikibudo. www.daito-ryu.com. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Daito Ryu Aiki Jujutsu Takumakai. "The Takumakai: An Outline". www.asahi-net.or.jp. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Daibukan Dojo (2003). "Information on the Daibukan". Daibukan @ Daitoryu Aiki Jujutsu. Daibukan Dojo. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ www.koryukan.com. "Interview with Okabayashi Sensei, founder and headmaster of Daito Ryu Hakuho Kai, and Rod Ulher as interpreter.". Articles And Events. www.koryukan.com. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (January 1990). "On separate language editions, Seigo Okamoto and Hakko-ryu Jujutsu". Aiki News 83. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article?articleID=9. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (Spring 1990). "Interview with Seigo Okamoto Shihan (02)". Aiki News 84. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article?articleID=402&highlight=kodokai. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Roppokai (2005). "History". Information. www.daitoryu-roppokai.org. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Yonezawa, Katsumi". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Tung, Tim (2005). "Links". TungBudo.com. Cat and Moon Productions. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Sagawa, Yukiyoshi". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Wollow, Paul. "Report on Sagawa-ha Daito-ryu Aikibujutsu". Aikido Journal. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article.php?articleID=242. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Draeger, Donn F. (February 1, 1996). Modern Bujutsu & Budo: The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan, Volume Three. Boston, Massachusetts: Weatherhill. ISBN 978-0834803510.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Pranin, Stanley (Summer 1992). "Interview with Katsuyuki Kondo (2)". Aiki News 92. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article.php?articleID=311. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2007). "Hiden Ogi (No Koto)". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2007). "Goshin'yo No Te". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Daito Ryu Aiki Jujutsu Takumakai. "Techniques". The System of Techniques of Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu. www.asahi-net.or.jp. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Soden". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (January 1989). "Daito-Ryu Aiki Jujutsu: The Present State of Affairs". Aiki News 79. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article?articleID=439. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2007). "Preface to the Print Edition". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Shodokan Aikido International Headquarters (2007). "Morihei Ueshiba and Kenji Tomiki". History of aikido. Shodokan HQ. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Tomiki, Kenji". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Ohlenkamp, Neil; Allen Gordon (2005). "Forms of Self Defense: Kodokan Goshin Jutsu". JudoInfo Online Dojo. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Shodokan Aikido International Headquarters (2007). "Shodokan and the Japan Aikido Association". Shodokan HQ. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Pranin, Stanley (2007). "Choi, Yong Sul". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Retrieved on 2007-07-21.

Further reading

- Profiles of several teachers mentioned above.

- Essay on Daito-ryu Aikijujutsu succession (PDF)

- On training with Yukiyoshi Sagawa