DNA replication

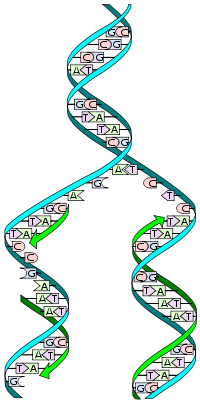

DNA replication, the basis for biological inheritance, is a fundamental process occurring in all living organisms to copy their DNA. This process is "semiconservative" in that each strand of the original double-stranded DNA molecule serves as template for the reproduction of the complementary strand. Hence, following DNA replication, two identical DNA molecules have been produced from a single double-stranded DNA molecule. Cellular proofreading and error-checking mechanisms ensure near perfect fidelity for DNA replication.[1][2]

In a cell, DNA replication begins at specific locations in the genome, called "origins".[3] Unwinding of DNA at the origin, and synthesis of new strands, forms a replication fork. In addition to DNA polymerase, the enzyme that synthesizes the new DNA by adding nucleotides matched to the template strand, a number of other proteins are associated with the fork and assist in the initiation and continuation of DNA synthesis.

DNA replication can also be performed in vitro (outside a cell). DNA polymerases, isolated from cells, and artificial DNA primers are used to initiate DNA synthesis at known sequences in a template molecule. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a common laboratory technique, employs such artificial synthesis in a cyclic manner to amplify a specific target DNA fragment from a pool of DNA.

Contents |

DNA structure

DNA usually exists in a double-stranded structure, with both strands coiled together to form the characteristic double-helix. Each single strand of DNA is a chain of four types of nucleotide: adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. A nucleotide consists of a phosphate and a deoxyribose sugar forming the backbone of the DNA double helix plus a base that points inwards. Nucleotides are matched between strands through hydrogen bonds to form base pairs. Adenine pairs with thymine and cytosine pairs with guanine.

The physical pairing of bases in DNA means that the information contained within each strand is redundant. The nucleotides on a single strand can be used to reconstruct nucleotides on a newly synthesized partner strand.

DNA strands have a directionality, and the different ends of a single strand are called the "3' end" and the "5' end" (these refer to the carbon atom in ribose that the next phosphate in the chain attaches to). In addition to being complementary, the two strands of DNA are antiparallel: they are orientated in opposite directions. This directionality has consequences in DNA synthesis, because DNA polymerase can only synthesize DNA in one direction by adding nucleotides to the 3' end of a DNA strand.

DNA polymerase

DNA polymerases are a family of enzymes critical for all forms of DNA replication.[4] A DNA polymerase synthesizes a new strand of DNA by extending the 3' end of an existing nucleotide chain, adding new nucleotides matched to the template strand one at a time. Some DNA polymerases may also have some proofreading ability, removing nucleotides from the end of a strand in order to remove any mismatched bases. DNA polymerases are generally extremely accurate, making less than one error for every 107 nucleotides added.

The energy for the process of DNA polymerization comes from the two additional phosphates attached to each of the unincorporated nucleotides. These free nucleotides, also known as nucleoside triphosphates, contain a total of three phosphates. When a nucleotide is being added to a growing DNA strand, two of the phosphates are removed and the energy produced is used to attach the remaining phosphate to the growing chain. The energetics of this process may also explain the directionality of synthesis - if DNA were synthesized in the 3' to 5' direction, the energy for the process would come from the 5' end of the growing strand rather than from free nucleotides. During proofreading, if the 5' nucleotide needed to be removed this triphosphate end would be lost, losing the energy source required to add a new nucleotide to the end.

DNA polymerase can only extend an existing DNA strand paired with a template strand, it cannot begin the synthesis of a new strand. To do this a short fragment of DNA or RNA, called a primer, must be created and paired with the template strand before DNA polymerase can synthesize new DNA.

DNA replication within the cell

Origins of replication

For a cell to divide, it must first replicate itself into newer ones DNA.[5] This process is initiated at particular points within the DNA, known as "origins", which are targeted by proteins that separate the two strands and initiate DNA synthesis.[3] Origins contain DNA sequences recognized by replication initiator proteins (eg. dnaA in E coli' and the Origin Recognition Complex in yeast).[6] These initiator proteins recruit other proteins to separate the two strands and initiate replication forks.

Initiator proteins recruit other proteins to separate the DNA strands at the origin, forming a bubble. Origins tend to be "AT-rich" (rich in adenine and thymine bases) to assist this process because A-T base pairs have two hydrogen bonds (rather than the three formed in a C-G pair)—strands rich in these nucleotides are generally easier to separate.[7] Once strands are separated, RNA primers are created on the template strands and DNA polymerase extends these to create newly synthesized DNA.

As DNA synthesis continues, the original DNA strands continue to unwind on each side of the bubble, forming replication forks. In bacteria, which have a single origin of replication on their circular chromosome, this process eventually creates a "theta structure" (resembling the Greek letter theta: θ). In contrast, eukaryotes have longer linear chromosomes and initiate replication at multiple origins within these.

The replication fork

The replication fork is a structure which forms when DNA is being replicated. It is created through the action of helicase, which breaks the hydrogen bonds holding the two DNA strands together. The resulting structure has two branching "prongs", each one made up of a single strand of DNA.

- Leading strand synthesis

In DNA replication, the leading strand is defined as the new DNA strand at the replication fork that is synthesized in the 5'→3' direction in a continuous manner. When the enzyme helicase unwinds DNA, two single stranded regions of DNA (the "replication fork") form. On the leading strand DNA polymerase III is able to synthesize DNA using the free 3' OH group donated by a single RNA primer and continuous synthesis occurs in the direction in which the replication fork is moving.

- Lagging strand synthesis

The lagging strand is the DNA strand at the opposite side of the replication fork from the leading strand, running in the 3' to 5' direction. Because DNA polymerase cannot synthesize in the 3'→5' direction, the lagging strand is synthesized in short segments known as Okazaki fragments. Along the lagging strand's template, primase builds RNA primers in short bursts. DNA polymerases are then able to use the free 3' OH groups on the RNA primers to synthesize DNA in the 5'→3' direction. The RNA fragments are then removed (different mechanisms are used in eukaryotes and prokaryotes) and new deoxyribonucleotides are added to fill the gaps where the RNA was present. DNA ligase then joins the deoxyribonucleotides together, completing the synthesis of the lagging strand.

- Dynamics at the replication fork

As helicase unwinds DNA at the replication fork, the DNA ahead is forced to rotate. This process results in a build-up of twists in the DNA ahead.[8] This build-up would form a resistance that would eventually halt the progress of the replication fork. DNA topoisomerases are enzymes that solve these physical problems in the coiling of DNA. Topoisomerase I cuts a single backbone on the DNA, enabling the strands to swivel around each other to remove the build-up of twists. Topoisomerase II cuts both backbones, enabling one double-stranded DNA to pass through another, thereby removing knots and entanglements that can form within and between DNA molecules.

Bare single-stranded DNA has a tendency to fold back upon itself and form secondary structures; these structures can interfere with the movement of DNA polymerase. To prevent this, single-strand binding proteins bind to the DNA until a second strand is synthesized, preventing secondary structure formation.[9]

Clamp proteins form a sliding clamp around DNA, helping the DNA polymerase maintain contact with its template and thereby assisting with processivity. The inner face of the clamp enables DNA to be threaded through it. Once the polymerase reaches the end of the template or detects double stranded DNA, the sliding clamp undergoes a conformational change which releases the DNA polymerase. Clamp-loading proteins are used to initially load the clamp, recognizing the junction between template and RNA primers.

Regulation of replication

- Eukaryotes

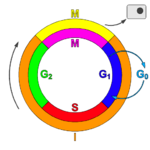

Within eukaryotes, DNA replication is controlled within the context of the cell cycle. As the cell grows and divides, it progresses through stages in the cell cycle; DNA replication occurs during the S phase (Synthesis phase). The progress of the eukaryotic cell through the cycle is controlled by cell cycle checkpoints. Progression through checkpoints is controlled through complex interactions between various proteins, including cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases.[10]

The G1/S checkpoint (or restriction checkpoint) regulates whether eukaryotic cells enter the process of DNA replication and subsequent division. Cells which do not proceed through this checkpoint are quiescent in the "G0" stage and do not replicate their DNA.

Replication of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes occurs independent of the cell cycle, through the process of D-loop replication.

- Bacteria

Most bacteria do not go through a well-defined cell cycle and instead continuously copy their DNA; during rapid growth this can result in multiple rounds of replication occurring concurrently.[11] Within E coli, the most well-characterized bacteria, regulation of DNA replication can be achieved through several mechanisms, including: the hemimethylation and sequestering of the origin sequence, the ratio of ATP to ADP, and the levels of protein DnaA. These all control the process of initiator proteins binding to the origin sequences.

Because E coli methylates GATC DNA sequences, DNA synthesis results in hemimethylated sequences. This hemimethylated DNA is recognized by a protein (SeqA) which binds and sequesters the origin sequence; in addition, dnaA (required for initiation of replication) binds less well to hemimethylated DNA. As a result, newly replicated origins are prevented from immediately initiating another round of DNA replication.[12]

ATP builds up when the cell is in a rich medium, triggering DNA replication once the cell has reached a specific size. ATP competes with ADP to bind to DnaA, and the DnaA-ATP complex is able to initiate replication. A certain number of DnaA proteins are also required for DNA replication — each time the origin is copied the number of binding sites for DnaA doubles, requiring the synthesis of more DnaA to enable another initiation of replication.

Termination of replication

Because bacteria have circular chromosomes, termination of replication occurs when the two replication forks meet each other on the opposite end of the parental chromosome. E coli regulate this process through the use of termination sequences which, when bound by the Tus protein, enable only one direction of replication fork to pass through. As a result, the replication forks are constrained to always meet within the termination region of the chromosome.[13]

Eukaryotes initiate DNA replication at multiple points in the chromosome, so replication forks meet and terminate at many points in the chromosome; these are not known to be regulated in any particular manner. Because eukaryotes have linear chromosomes, DNA replication often fails to synthesize to the very end of the chromosomes (telomeres), resulting in telomere shortening. This is a normal process in somatic cells — cells are only able to divide a certain number of times before the DNA loss prevents further division. (This is known as the Hayflick limit.) Within the germ cell line, which passes DNA to the next generation, the enzyme telomerase extends the repetitive sequences of the telomere region to prevent degradation. Telomerase can become mistakenly active in somatic cells, sometimes leading to cancer formation.

Rolling circle replication

Another method of copying DNA, sometimes used in vivo by bacteria and viruses, is the process of rolling circle replication.[14] In this form of replication, a single replication fork progresses around a circular molecule to form multiple linear copies of the DNA sequence. In cells, this process can be used to rapidly synthesize multiple copies of plasmids or viral genomes.

In the cell, rolling circle replication is initiated by an initiator protein encoded by the plasmid or virus DNA. This protein is able to nick one strand of the double-stranded, circular DNA molecule at a site called the double-strand origin (DSO) and remains bound to the 5' phosphate end of the nicked strand. The free 3' hydroxyl end is released and can serve as a primer for DNA synthesis. Using the unnicked strand as a template, replication proceeds around the circular DNA molecule, displacing the nicked strand as single-stranded DNA. Continued DNA synthesis produces multiple single-stranded linear copies of the original DNA in a continuous head-to-tail series. In vivo these linear copies are subsequently converted to double-stranded circular molecules.

Rolling circle replication can also be performed in vitro and has found wide uses in academic research and biotechnology, often used for amplification of DNA from very small amounts of starting material. Replication can be initiated by nicking a double-stranded circular DNA molecule or by hybridizing a primer to a single-stranded circle of DNA. The use of a reverse primer (or random primers) produces hyperbranched rolling circle amplification, resulting in exponential rather than linear growth of the DNA molecule.

Polymerase chain reaction

In vitro, researchers commonly replicate DNA using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR uses a pair of primers to span a target region in template DNA, polymerizing partner strands in each direction. This process can be repeated through multiple cycles through the use of a thermostable polymerase. At the start of each cycle, the mixture of template and primers is heated, separating the newly synthesized molecule and template. Then, as the mixture cools, both of these become templates for new primers to anneal to, and the polymerase extends from these. As a result the number of copies of the target region doubles each round, growing exponentially.

See also

- Replicon (genetics)

- Replicative transposition

- Replisome

- Self-replication

- Viral replication

References

- ↑ Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L, Clarke ND (2002). Biochemistry. W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-3051-0. Chapter 27: DNA Replication, Recombination, and Repair

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. Chapter 5: DNA Replication, Repair, and Recombination

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L, Clarke ND (2002). Biochemistry. W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-3051-0.Chapter 27, Section 4: DNA Replication of Both Strands Proceeds Rapidly from Specific Start Sites

- ↑ Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L, Clarke ND (2002). Biochemistry. W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-3051-0. Chapter 27, Section 2: DNA Polymerases Require a Template and a Primer

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. Chapter 5: DNA Replication Mechanisms

- ↑ C Weigel, A Schmidt, B Rückert, R Lurz, and W Messer (1997). "DnaA protein binding to individual DnaA boxes in the Escherichia coli replication origin, oriC". EMBO Journal 16 (21): 6574–6583. doi:. PMID 9351837. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1170261.

- ↑ Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky LS, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J (2000). Molecular Cell Biology. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-3136-3.12.1. General Features of Chromosomal Replication: Three Common Features of Replication Origins

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. DNA Replication Mechanisms: DNA Topoisomerases Prevent DNA Tangling During Replication

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. DNA Replication Mechanisms: Special Proteins Help to Open Up the DNA Double Helix in Front of the Replication Fork

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1. Intracellular Control of Cell-Cycle Events: S-Phase Cyclin-Cdk Complexes (S-Cdks) Initiate DNA Replication Once Per Cycle

- ↑ Tobiason DM, Seifert HS (2006). "The Obligate Human Pathogen, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Is Polyploid". PLoS Biology 4 (6): e185. doi:.

- ↑ Slater S, Wold S, Lu M, Boye E, Skarstad K, Kleckner N (1995). "E. coli SeqA protein binds oriC in two different methyl-modulated reactions appropriate to its roles in DNA replication initiation and origin sequestration.". Cell 82 (6): 927-36. doi:. PMID 7553853. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7553853.

- ↑ TA Brown (2002). Genomes. BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd. ISBN 1 85996 228 9.13.2.3. Termination of replication

- ↑ Griffiths AJF, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, Lewontin RC, Gelbart WM (2000). An Introduction to Genetic Analysis. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3520-2. Chapter 8 Replication of DNA: Rolling-circle replication

External links

- DNA Replication Flash Animation DNA Replication tutorial animation

- DNA Workshop

- WEHI-TV - DNA Replication video Detailed DNA replication animation from different angles with description below.

- Breakfast of Champions Does Replication Creative primer on the process from the Science Creative Quarterly

- Basic Polymerase Chain Reaction Protocol

- Animated Biology

- DNA makes DNA (Flash Animation)

- DNA replication info page by George Kakaris, Biologist MSc in Applied Genetics and Biotechnology

- Reference website on eukaryotic DNA replication

- Molecular visualization of DNA Replication

|

|||||||||||