Cytomegalovirus

| Cytomegalovirus Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-10 | B25. |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 078.5 |

| MeSH | D003586 |

| Cytomegalovirus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CMV infection of a lung pneumocyte.

|

||||||

| Virus classification | ||||||

|

||||||

| Species | ||||||

|

see text |

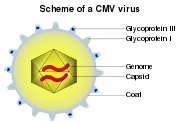

Cytomegalovirus (from the Greek cyto-, "cell", and -megalo-, "large") is a viral genus of the Herpesviruses group: in humans it is commonly known as HCMV or Human Herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5).[1] CMV belongs to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily of Herpesviridae, which also includes Roseolovirus. Other herpesviruses fall into the subfamilies of Alphaherpesvirinae (including HSV 1 and 2 and varicella) or Gammaherpesvirinae (including Epstein-Barr virus).[1] All herpesviruses share a characteristic ability to remain latent within the body over long periods.

HCMV infections are frequently associated with salivary glands, though they may be found throughout the body. HCMV infection can also be life threatening for patients who are immunocompromised (e.g. patients with HIV, organ transplant recipients, or neonates).[1] Other CMV viruses are found in several mammal species, but species isolated from animals differ from HCMV in terms of genomic structure, and have not been reported to cause human disease.

HCMV is found throughout all geographic locations and socioeconomic groups, and infects between 50% and 80% of adults in the United States as indicated by the presence of antibodies in much of the general population.[1] Seroprevalence is age-dependent: 58.9% of individuals aged 6 and over are infected with CMV while 90.8% of individuals aged 80 and over are positive for HCMV.[2] HCMV is also the virus most frequently transmitted to a developing fetus. HCMV infection is more widespread in developing countries and in communities with lower socioeconomic status and represents the most significant viral cause of birth defects in industrialized countries.

Contents |

Species

| Name | Abv. | Host |

|---|---|---|

| Cercopithecine herpesvirus 5 | (CeHV-5) | African green monkey |

| Cercopithecine herpesvirus 8 | (CeHV-8) | Rhesus monkey |

| Human herpesvirus 5 | (HHV-5) | Humans |

| Pongine herpesvirus 4 | (PoHV-4) | ? |

| Aotine herpesvirus 1 | (AoHV-1) | (Tentative species) |

| Aotine herpesvirus 3 | (AoHV-3) | (Tentative species) |

Pathogenesis

Most healthy people who are infected by HCMV after birth have no symptoms.[1] Some of them develop an infectious mononucleosis/glandular fever-like syndrome,[3] with prolonged fever, and a mild hepatitis. A sore throat is common. After infection, the virus remains latent in the body for the rest of the person's life. Overt disease rarely occurs unless immunity is suppressed either by drugs, infection or old-age. Initial HCMV infection, which often is asymptomatic is followed by a prolonged, inapparent infection during which the virus resides in cells without causing detectable damage or clinical illness.

Infectious CMV may be shed in the bodily fluids of any infected person, and can be found in urine, saliva, blood, tears, semen, and breast milk. The shedding of virus can occur intermittently, without any detectable signs or symptoms.

CMV infection can be demonstrated microscopically by the detection of intranuclear inclusion bodies. The inclusion bodies stain dark pink by H&E staining, and are called "Owl's Eye" inclusion bodies.[4]

HCMV infection is important to certain high-risk groups.[5] Major areas of risk of infection include pre-natal or postnatal infants and immunocompromised individuals, such as organ transplant recipients, persons with leukemia, or those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HCMV is considered an AIDS-defining infection, indicating that the T-cell count has dropped to low levels.

Lytically replicating virus disrupts the cytoskeleton, causing massive cell enlargement, which is the source of the virus' name.

Transmission and prevention

Transmission of HCMV occurs from person to person through bodily fluids. Infection requires close, intimate contact with a person excreting the virus in their saliva, urine, or other bodily fluids. CMV can be sexually transmitted and can also be transmitted via breast milk, transplanted organs, and rarely from blood transfusions.

Although HCMV is not highly contagious, it has been shown to spread in households and among young children in day care centers.[1] Transmission of the virus is often preventable because it is most often transmitted through infected bodily fluids that come in contact with hands and then are absorbed through the nose or mouth of a susceptible person. Therefore, care should be taken when handling children and items like diapers. Simple hand washing with soap and water is effective in removing the virus from the hands.

HCMV infection without symptoms is common in infants and young children; as a result, it is common not to exclude from school or an institution a child known to be infected. Similarly, hospitalized patients are not typically separated or isolated.

CMV diseases

The most common types of infections by CMV can be group as follows:

- Fetus/Infant

- Congenital CMV infection

- Perinatal CMV infection

- Immunocompetent patient

- CMV mononucleosis

- Post-transfusion CMV - similar to CMV mononucleosis

- Immunocompromised patient

- CMV pneumonitis

- CMV GI disease

- CMV retinitis

Pregnancy and congenital infection

HCMV forms part of the association known as TORCH infections that lead to congenital abnormalities. These include Toxoplasmosis, Rubella, Herpes simplex, as well as HCMV, among others. Congenital HCMV infection occurs when the mother suffers a primary infection (or reactivation) during pregnancy. Due to the lower seroprevalence of HCMV in industrialized countries and higher socioeconomic groups, congenital infections are actually more common than in poorer communities, where more women of child-bearing age are already seropositive. In industrialized countries up to 8% of HCMV seronegative mothers contract primary HCMV infection during pregnancy, of which roughly 50% will transmit to the fetus.[6] Between 22-38% of infected fetuses are then born with symptoms,[7] which may include pneumonia, gastrointestinal, retinal and neurological disease.[8][9] HCMV infection occurs in roughly 1% of all neonates with those who are not congenitally infected contracting the infection possibly through breast milk.[10][11][12] Other sources of neonatal infection are bodily fluids which are known to contain high titres in shedding individuals: Saliva (<107copies/ml) and urine (<105copies/ml )[13][14] seem common routes of transmission.

The incidence of primary CMV infection in pregnant women in the United States varies from 1% to 3%. Healthy pregnant women are not at special risk for disease from CMV infection. When infected with CMV, most women have no symptoms and very few have a disease resembling mononucleosis. It is their developing fetuses that may be at risk for congenital CMV disease. CMV remains the most important cause of congenital viral infection in the United States. HCMV is the most common cause of congenital infection in humans and intrauterine primary infections are second only to Down's syndrome as a known cause of mental retardation.[15]

For infants who are infected by their mothers before birth, two potential adverse scenarios exist:

- Generalized infection may occur in the infant, and can cause complications such as low birth weight, microcephaly, seizures, petechial rash similar to the "blueberry muffin" rash of congenital rubella syndrome, and moderate hepatosplenomegaly (with jaundice). Though severe cases can be fatal, with supportive treatment most infants with CMV disease will survive. However, from 80% to 90% will have complications within the first few years of life that may include hearing loss, vision impairment, and varying degrees of mental retardation.

- Another 5% to 10% of infants who are infected but without symptoms at birth will subsequently have varying degrees of hearing and mental or coordination problems.

However, these risks appear to be almost exclusively associated with women who previously have not been infected with CMV and who are having their first infection with the virus during pregnancy. Even in this case, two-thirds of the infants will not become infected, and only 10% to 15% of the remaining third will have symptoms at the time of birth. There appears to be little risk of CMV-related complications for women who have been infected at least 6 months prior to conception. For this group, which makes up 50% to 80% of the women of child-bearing age, the rate of newborn CMV infection is 1%, and these infants appear to have no significant illness or abnormalities.[1]

The virus can also be transmitted to the infant at delivery from contact with genital secretions or later in infancy through breast milk. However, these infections usually result in little or no clinical illness in the infant.

To summarize, during a pregnancy when a woman who has never had CMV infection becomes infected with CMV, there is a potential risk that after birth the infant may have CMV-related complications, the most common of which are associated with hearing loss, visual impairment, or diminished mental and motor capabilities. On the other hand, infants and children who acquire CMV after birth have few, if any, symptoms or complications.

Recommendations for pregnant women with regard to CMV infection:

- Throughout the pregnancy, practice good personal hygiene, especially handwashing with soap and water, after contact with diapers or oral secretions (particularly with a child who is in day care).

- Women who develop a mononucleosis-like illness during pregnancy should be evaluated for CMV infection and counseled about the possible risks to the unborn child.

- Laboratory testing for antibody to CMV can be performed to determine if a women has already had CMV infection.

- Recovery of CMV from the cervix or urine of women at or before the time of delivery does not warrant a cesarean section.

- The demonstrated benefits of breast-feeding outweigh the minimal risk of acquiring CMV from the breast-feeding mother.

- There is no need to either screen for CMV or exclude CMV-excreting children from schools or institutions because the virus is frequently found in many healthy children and adults.

Childcare

Most healthy people working with infants and children face no special risk from CMV infection. However, for women of child-bearing age who previously have not been infected with CMV, there is a potential risk to the developing unborn child (the risk is described above in the Pregnancy section). Contact with children who are in day care, where CMV infection is commonly transmitted among young children (particularly toddlers), may be a source of exposure to CMV. Since CMV is transmitted through contact with infected body fluids, including urine and saliva, child care providers (meaning day care workers, special education teachers, as well as mothers) should be educated about the risks of CMV infection and the precautions they can take. Day care workers appear to be at a greater risk than hospital and other health care providers, and this may be due in part to the increased emphasis on personal hygiene in the health care setting.

Recommendations for individuals providing care for infants and children:

- Employees should be educated concerning CMV, its transmission, and hygienic practices, such as handwashing, which minimize the risk of infection.

- Susceptible nonpregnant women working with infants and children should not routinely be transferred to other work situations.

- Pregnant women working with infants and children should be informed of the risk of acquiring CMV infection and the possible effects on the unborn child.

- Routine laboratory testing for CMV antibody in female workers is not specifically recommended due to its high occurrence, but can be performed to determine their immune status.

Immunocompromised patients

Primary CMV infection in patients with weakened immune systems can lead to serious disease. However, more common problem is reactivation of the latent virus.

In patients with a depressed immune system, CMV-related disease may be much more aggressive. CMV hepatitis may cause fulminant liver failure. Specific disease entities recognised in those people are cytomegalovirus retinitis (inflammation of the retina, characterised by a "pizza pie appearance" on ophthalmoscopy) and cytomegalovirus colitis (inflammation of the large bowel).

Infection with CMV is a major cause of disease and death in immunocompromised patients, including organ transplant recipients, patients undergoing hemodialysis, patients with cancer, patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs, and HIV-infected patients. Exposing immunosuppressed patients to outside sources of CMV should be minimized to avoid the risk of serious infection. Whenever possible, patients without CMV infection should be given organs and/or blood products that are free of the virus.

Patients without CMV infection who are given organ transplants from CMV-infected donors should be given prophylactic treatment with valganciclovir (ideally) or ganciclovir and require regular serological monitoring to detect a rising CMV titre, which should be treated early to prevent a potentially life-threatening infection becoming established.

Diagnosis

Most infections with CMV are not diagnosed because the virus usually produces few, if any, symptoms and tends to reactivate intermittently without symptoms. However, persons who have been infected with CMV develop antibodies to the virus, and these antibodies persist in the body for the lifetime of that individual. A number of laboratory tests that detect these antibodies to CMV have been developed to determine if infection has occurred and are widely available from commercial laboratories. In addition, the virus can be cultured from specimens obtained from urine, throat swabs, bronchial lavages and tissue samples to detect active infection. Both qualitative and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for CMV are available as well, allowing physicians to monitor the viral load of CMV-infected patients.

CMV pp65 antigenemia test is a immunofluorescence based assay which utilizes an indirect immunofluorescence technique for identifying the pp65 protein of cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood leukocytes. The CMV pp65 assay is widely used for monitoring CMV infections and its response to antiviral treatment in patients who are under immunosuppressive therapy and have had renal transplantation surgery as the Antigenemia results are obtained ~ 5 days before the onset of symptomatic CMV disease. The advantage of this assay is the rapidity in providing results in a few hours and that the pp65 antigen determination represents a useful parameter for the physician to initiate antiviral therapy. The major disadvantage of the pp65 assay is that only limited number of samples can be processed per test batch.

CMV should be suspected if a patient has symptoms of infectious mononucleosis but has negative test results for mononucleosis and Epstein-Barr virus, or if they show signs of hepatitis, but has negative test results for hepatitis A, B, and C.

For best diagnostic results, laboratory tests for CMV antibody should be performed by using paired serum samples. One blood sample should be taken upon suspicion of CMV, and another one taken within 2 weeks. A virus culture can be performed at any time the patient is symptomatic. Laboratory testing for antibody to CMV can be performed to determine if a woman has already had CMV infection. However, routine testing of all pregnant women is costly and the need for testing should therefore be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Serologic testing

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (or ELISA) is the most commonly available serologic test for measuring antibody to CMV. The result can be used to determine if acute infection, prior infection, or passively acquired maternal antibody in an infant is present. Other tests include various fluorescence assays, indirect hemagglutination, (PCR) and latex agglutination.

An ELISA technique for CMV-specific IgM is available, but may give false-positive results unless steps are taken to remove rheumatoid factor or most of the IgG antibody before the serum sample is tested. Because CMV-specific IgM may be produced in low levels in reactivated CMV infection, its presence is not always indicative of primary infection. Only virus recovered from a target organ, such as the lung, provides unequivocal evidence that the current illness is caused by acquired CMV infection. If serologic tests detect a positive or high titer of IgG, this result should not automatically be interpreted to mean that active CMV infection is present. However, if antibody tests of paired serum samples show a fourfold rise in IgG antibody and a significant level of IgM antibody, meaning equal to at least 30% of the IgG value, or virus is cultured from a urine or throat specimen, the findings indicate that an active CMV infection is present.

Relevance to blood donors

Although the risks discussed above are generally low, CMV assays are part of the standard screening for non-directed blood donation (donations not specified for a particular patient) in the U.S. CMV-negative donations are then earmarked for transfusion to infants or immunocompromised patients. Some blood donation centers maintain lists of donors whose blood is CMV negative due to special demands.[16]

Treatment

Cytomegalovirus Immune Globulin Intravenous (Human) (CMV-IGIV), is an immunoglobulin G (IgG) containing a standardized amount of antibody to Cytomegalovirus (CMV). It may be used for the prophylaxis of cytomegalovirus disease associated with transplantation of kidney, lung, liver, pancreas, and heart.

Alone or in combination with an antiviral agent, it has been shown to:

- Reduce the risk of CMV-related disease and death in some of the highest-risk transplant patients

- Provide a measurable long-term survival benefit

- Produce minimal treatment-related side effects and adverse events. [17]

Ganciclovir treatment is used for patients with depressed immunity who have either sight-related or life-threatening illnesses. Valganciclovir (marketed as Valcyte) is an antiviral drug that is also effective and is given orally. The therapeutic effectiveness is frequently compromised by the emergence of drug-resistant virus isolates. A variety of amino acid changes in the UL97 protein kinase and the viral DNA polymerase have been reported to cause drug resistance. Foscarnet or cidofovir can be given in patients with CMV resistant to ganciclovir, because foscarnet has bad nephrotoxicity, increased or decreased Ca2+ or P, and decreased Mg2+. Vaccines are still in the research and development stage.

Genomics

As a result of efforts to create an attenuated-virus vaccine, there currently exist two general classes of CMV.

- Clinical isolates comprise those viruses obtained from patients and represent the wild-type viral genome.

- Laboratory strains have been cultured extensively in the lab setting and typically contain numerous accumulated mutations. Most notably, the laboratory strain AD169 appears to lack a 15kb region of the 200kb genome that is present in clinical isolates. This region contains 19 open reading frames whose functions have yet to be elucidated. AD169 is also unique in that it is unable to enter latency and nearly always assumes lytic growth upon infection.

External links

- CDC information on cytomegalovirus

- CMV Seronegative vs. Leucodepleted blood components for at risk recipients.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

- Learn about CMV prophylaxis and high risk transplants at Cytogam.com

- Stop CMV (CMV Action Network) - Organization and website dedicated to raising public awareness about Congenital CMV, www.stopcmv.com

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. pp. 556; 566–9. ISBN 0838585299.

- ↑ Staras SAS, Dollard SC, Radford KW, et al. (2006). "Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988–1994". Clin Infect Dis 43: 1143–51. doi:. PMID 17029132.

- ↑ Bottieau E, Clerinx J, Van den Enden E, et al (2006). "Infectious mononucleosis-like syndromes in febrile travelers returning from the tropics". J Travel Med 13 (4): 191–7. doi:. PMID 16884400. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1195-1982&date=2006&volume=13&issue=4&spage=191.

- ↑ Mattes FM, McLaughlin JE, Emery VC, Clark DA, Griffiths PD (2000). "Histopathological detection of owl's eye inclusions is still specific for cytomegalovirus in the era of human herpesviruses 6 and 7". J. Clin. Pathol. 53 (8): 612–4. PMID 11002765. PMC: 1762915. http://jcp.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11002765.

- ↑ Bennekov T, Spector D, Langhoff E (2004). "Induction of immunity against human cytomegalovirus". Mt. Sinai J. Med. 71 (2): 86–93. PMID 15029400. http://www.mssm.edu/msjournal/71/71286.shtml.

- ↑ Adler SP (2005). "Congenital cytomegalovirus screening". Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24 (12): 1105–6. PMID 16371874. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0891-3668&volume=24&issue=12&spage=1105.

- ↑ Griffiths PD, Walter S (2005). "Cytomegalovirus". Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 18 (3): 241–5. PMID 15864102. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0951-7375&volume=18&issue=3&spage=241.

- ↑ Barry Schoub; Zuckerman, Arie J.; Banatvala, Jangu E.; Griffiths, Paul E. (2004). "Chapter 2C Cytomegalovirus". Principles and Practice of Clinical Virology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–122. ISBN 0-470-84338-1.

- ↑ Vancíková Z, Dvorák P (2001). "Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals--a review". Curr. Drug Targets Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. 1 (2): 179–87. PMID 12476798. http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=1568-0088&volume=1&issue=2&spage=179&aulast=Vancíková.

- ↑ Kerrey BT, Morrow A, Geraghty S, Huey N, Sapsford A, Schleiss MR (2006). "Breast milk as a source for acquisition of cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in a premature infant with sepsis syndrome: detection by real-time PCR". J. Clin. Virol. 35 (3): 313–6. doi:. PMID 16300992. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1386-6532(05)00274-X.

- ↑ Schleiss MR (2006). "Role of breast milk in acquisition of cytomegalovirus infection: recent advances". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 18 (1): 48–52. doi:. PMID 16470162. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?an=00008480-200602000-00010.

- ↑ Schleiss MR (2006). "Acquisition of human cytomegalovirus infection in infants via breast milk: natural immunization or cause for concern?". Rev. Med. Virol. 16 (2): 73–82. doi:. PMID 16287195.

- ↑ Kearns AM, Turner AJ, Eltringham GJ, Freeman R (2002). "Rapid detection and quantification of CMV DNA in urine using LightCycler-based real-time PCR". J. Clin. Virol. 24 (1-2): 131–4. PMID 11744437. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1386653201002402.

- ↑ Yoshikawa T, Ihira M, Taguchi H, Yoshida S, Asano Y (2005). "Analysis of shedding of 3 beta-herpesviruses in saliva from patients with connective tissue diseases". J. Infect. Dis. 192 (9): 1530–6. doi:. PMID 16206067. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/resolve?JID34797.

- ↑ (Article: Bio Protection And Licencing in Europe, p.5, Les Nouvelles, March 2000, ISSN 0270-174X)

- ↑ "United Blood Services FAQs". Retrieved on 2007-05-23.

- ↑ http://www.cytogam.com/about_cytogam/default.aspx

Further reading

- Fletcher JM, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Dunne PJ, et al (2005). "Cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T cells in healthy carriers are continuously driven to replicative exhaustion". J. Immunol. 175 (12): 8218–25. PMID 16339561.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||