Cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator. Cyclotrons accelerate charged particles using a high-frequency, alternating voltage (potential difference). A perpendicular magnetic field causes the particles to spiral almost in a circle so that they re-encounter the accelerating voltage many times.

Ernest Lawrence, of the University of California, Berkeley, is credited with the invention of the cyclotron in 1929. Sándor Gaál first invented the device, but could not publish it, so the offical credit goes to Ernest Lawrence. He used it in experiments that required particles with energy of up to 1 MeV.

Contents |

How the cyclotron works

The electrodes shown at the right would be in the vacuum chamber, which is flat, in a narrow gap between the two poles of a large magnet.

In the cyclotron, a high-frequency alternating voltage applied across the "D" electrodes (also called "dees") alternately attracts and repels charged particles. The particles, injected near the center of the magnetic field, accelerate only when passing through the gap between the electrodes. The perpendicular magnetic field (passing vertically through the "D" electrodes), combined with the increasing energy of the particles forces the particles to travel in a spiral path.

With no change in energy the charged particles in a magnetic field will follow a circular path. In the cyclotron, energy is applied to the particles as they cross the gap between the dees and so they are accelerated (at the typical sub-relativistic speeds used) and will increase in mass as they approach the speed of light. Either of these effects (increased velocity or increased mass) will increase the radius of the circle and so the path will be a spiral.

(The particles move in a spiral, because a current of electrons or ions, flowing perpendicular to a magnetic field, experiences a perpendicular force. The charged particles move freely in a vacuum, so the particles follow a spiral path.)

The radius will increase until the particles hit a target at the perimeter of the vacuum chamber. Various materials may be used for the target, and the collisions will create secondary particles which may be guided outside of the cyclotron and into instruments for analysis. The results will enable the calculation of various properties, such as the mean spacing between atoms and the creation of various collision products. Subsequent chemical and particle analysis of the target material may give insight into nuclear transmutation of the elements used in the target.

Uses of the cyclotron

For several decades, cyclotrons were the best source of high-energy beams for nuclear physics experiments; several cyclotrons are still in use for this type of research.

Cyclotrons can be used to treat cancer. Ion beams from cyclotrons can be used, as in proton therapy, to penetrate the body and kill tumors by radiation damage, while minimizing damage to healthy tissue along their path.

Cyclotron beams can be used to bombard other atoms to produce short-lived positron-emitting isotopes suitable for PET imaging.

Problems solved by the cyclotron

The cyclotron was an improvement over the linear accelerators that were available when it was invented. A linear accelerator (also called a linac) accelerates particles in a straight line through an evacuated tube (or series of such tubes placed end to end). A set of electrodes shaped like flat donuts are arranged inside the length of the tube(s). These are driven by high-power radio waves that continuously switch between positive and negative voltage, causing particles traveling along the center of the tube to accelerate. In the 1920s, it was not possible to get high frequency radio waves at high power, so either the accelerating electrodes had to be far apart to accommodate the low frequency or more stages were required to compensate for the low power at each stage. Either way, higher-energy particles required longer accelerators than scientists could afford.

Modern linacs use high power Klystrons and other devices able to impart much more power at higher frequencies. But before these devices existed, cyclotrons were cheaper than linacs.

Cyclotrons accelerate particles in a spiral path. Therefore, a compact accelerator can contain much more distance than a linear accelerator, with more opportunities to accelerate the particles.

Advantages of the cyclotron

- Cyclotrons have a single electrical driver, which saves both money and power, since more expense may be allocated to increasing efficiency.

- Cyclotrons produce a continuous stream of particles at the target, so the average power is relatively high.

- The compactness of the device reduces other costs, such as its foundations, radiation shielding, and the enclosing building.

Limitations of the cyclotron

The spiral path of the cyclotron beam can only "synch up" with klystron-type (constant frequency) voltage sources if the accelerated particles are approximately obeying Newton's Laws of Motion. If the particles become fast enough that relativistic effects become important, the beam gets out of phase with the oscillating electric field, and cannot receive any additional acceleration. The cyclotron is therefore only capable of accelerating particles up to a few percent of the speed of light. To accommodate increased mass the magnetic field may be modified by appropriately shaping the pole pieces as in the isochronous cyclotrons, operating in a pulsed mode and changing the frequency applied to the dees as in the synchrocyclotrons, either of which is limited by the diminishing cost effectiveness of making larger machines. Cost limitations have been overcome by employing the more complex synchrotron or linear accelerator, both of which have the advantage of scalability, offering more power within an improved cost structure as the machines are made larger.

Mathematics of the cyclotron

Non-relativistic

The centripetal force is provided by the transverse magnetic field B, and the force on a particle travelling in a magnetic field (which causes it to be angularly displaced, i.e spiral) is equal to Bqv. So,

(Where m is the mass of the particle, q is its charge, v is its velocity and r is the radius of its path.)

The speed at which the particles enter the cyclotron due to a potential difference, V.

Therefore,

v/r is equal to angular velocity, ω, so

And since the angular frequency is

Therefore,

This shows that for a particle of constant mass, the frequency does not depend upon the radius of the particle's orbit. As the beam spirals out, its frequency does not decrease, and it must continue to accelerate, as it is travelling more distance in the same time. As particles approach the speed of light, they acquire additional mass, requiring modifications to the frequency, or the magnetic field during the acceleration. This is accomplished in the synchrocyclotron.

Relativistic

The radius of curvature for a particle moving relativistically in a static magnetic field is

- where

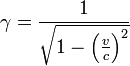

the Lorentz factor

the Lorentz factor

Note that in high-energy experiments energy, E, and momentum, p, are used rather than velocity, and both measured in units of energy. In that case one should use the substitution,

- where this is in Natural units

The relativistic cyclotron frequency is

,

,

- where

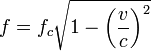

is the classical frequency, given above, of a charged particle with velocity

is the classical frequency, given above, of a charged particle with velocity circling in a magnetic field.

circling in a magnetic field.

The rest mass of an electron is 511 keV, so the frequency correction is 1% for a magnetic vacuum tube with a 5.11 kV direct current accelerating voltage. The proton mass is nearly two thousand times the electron mass, so the 1% correction energy is about 9 MeV, which is sufficient to induce nuclear reactions.

An alternative to the synchrocyclotron is the isochronous cyclotron, which has a magnetic field that increases with radius, rather than with time. The de-focusing effect of this radial field gradient is compensated by ridges on the magnet faces which vary the field azimuthally as well. This allows particles to be accelerated continuously, on every period of the radio frequency, rather than in bursts as in most other accelerator types. This principle that alternating field gradients have a net focusing effect is called strong focusing. It was obscurely known theoretically long before it was put into practice.

Related technologies

- The spiraling of electrons in a cylindrical vacuum chamber within a transverse magnetic field is also employed in the magnetron, a device for producing high frequency radio waves (microwaves).

- The Synchrotron moves the particles through a path of constant radius, allowing it to be made as a pipe and so of much larger radius than is practical with the cyclotron and synchrocyclotron. The larger radius allows the use of numerous magnets, each of which imparts angular momentum and so allows particles of higher velocity (mass) to be kept within the bounds of the evacuated pipe. The magnetic field strength of each of the bending magnets is increased as the particles gain energy in order to keep the bending angle constant.

See also

- Beamline

- cyclotron radiation, synchrotron light or its close relative, bremsstrahlung radiation.

- electron cyclotron resonance

- Gyrotron

- ion cyclotron resonance

- Linear accelerator

- Particle accelerator

- Storage ring

- synchrocyclotron

- synchrotron

- TRIUMF - largest cyclotron in the world

- Radiation reaction

External links

- U.S. Patent 1,948,384 -- Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions

- Indiana University Cyclotron Facility MPRI treats first patient using robotic gantry system.

- "The 88-Inch Cyclotron at LBNL"

- "The NSCL at Michigan State University" Home of coupled K500 and K1200 cyclotrons; the K500, being the first superconducting cyclotron and the K1200 currently the most powerful in the world.

- Rutgers Cyclotron and "Building a Cyclotron on a Shoestring" Tim Koeth, now a graduate student at Rutgers University, built a 12-inch 1 MeV cyclotron as an undergraduate project, which is now used for a senior-level undergraduate and a graduate lab course.

- "Cyclotron java applet"

- "Resonance Spectral Analysis with a Homebuilt Cyclotron" an experiment done by Fred M. Niell, III his senior year of high school (1994-95) with which he won the overall grand prize in the ISEF.

- Relativistic accelerator physics PDF

- Wired news article about a neighborhood cyclotron in Anchorage, Alaska

- web site of company IBA

- The Cyclotron Kids A group of high schooled students building their own 2.3 MeV cyclotron for experimentation.