Cushing's syndrome

| Cushing's syndrome Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

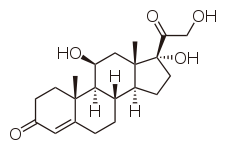

| Cortisol | |

| ICD-10 | E24. |

| ICD-9 | 255.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 3242 |

| MedlinePlus | 000410 |

| eMedicine | med/485 |

| MeSH | D003480 |

Cushing's syndrome (also called hyperadrenocorticism) is an endocrine disorder caused by high levels of cortisol in the blood. This hypercortisolism can be caused by intake of glucocorticoids, or by tumors that produce cortisol or ACTH.[1] Cushing's disease refers to one specific cause, namely an adenoma in the pituitary gland that produces large amounts of ACTH which in turn elevates cortisol.

Cushing's syndrome is not confined to humans and is also a relatively common condition in domestic dogs and horses. It was described by American Dr. Harvey Cushing in 1932.[2]

Contents |

Classification and Aetiology

There are several possible causes of Cushing's syndrome. The most common is exogenous administration of glucocorticoids prescribed by physicians to treat other diseases (called iatrogenic Cushing's). This can be an effect of steroid treatment of a variety of disorders such as asthma and rheumatoid arthritis, or in immunosuppression after an organ transplant. Administration of synthetic ACTH is also possible, but ACTH is less often prescribed due to cost and lesser utility.

Endogenous Cushing syndrome results from some derangement of the body's own system of secreting cortisol. Normally, ACTH is released from the pituitary gland when necessary to stimulate the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. In pituitary Cushing's, a benign pituitary adenoma secretes ACTH. This is also known as Cushing's disease and is responsible for 65% of endogenous Cushing's. In adrenal Cushing's, excess cortisol is produced by adrenal gland tumors, hyperplastic adrenal glands, or adrenal glands with nodular adrenal hyperplasia. Finally, tumors outside the normal pituitary-adrenal system can produce ACTH that affects the adrenal glands. This final etiology is called ectopic or paraneoplastic Cushing's and is seen in diseases like small cell lung cancer.

Cushing's syndrome can also be sub-classified according to whether or not the excess cortisol is dependent on increased ACTH. ACTH-dependent Cushing's is driven by increased ACTH and includes exogenous ACTH administration as well as pituitary and ectopic Cushing's. ACTH-independent Cushing's shows increased cortisol, but the ACTH is not elevated but rather decreased due to negative feedback. It can be caused by exogenous administration of glucocorticoids or by adrenal adenoma, carcinoma, or nodular hyperplasia.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include rapid weight gain, particularly of the trunk and face with sparing of the limbs (central obesity), a round face often referred to as a "moon face," excess sweating, telangiectasia (dilation of capillaries), thinning of the skin (which causes easy bruising) and other mucous membranes, purple or red striae (the weight gain in Cushing's stretches the skin, which is thin and weakened, causing it to hemorrhage) on the trunk, buttocks, arms, legs or breasts, proximal muscle weakness (hips, shoulders), and hirsutism (facial male-pattern hair growth). A common sign is the growth of fat pads along the collar bone and on the back of the neck (buffalo hump) (known as a lipodystrophy). The excess cortisol may also affect other endocrine systems and cause, for example, insomnia, reduced libido, impotence, amenorrhoea and infertility. Patients frequently suffer various psychological disturbances, ranging from euphoria to psychosis. Depression and anxiety are also common.[3]

Other signs include polyuria (and accompanying polydipsia), persistent hypertension (due to cortisol's enhancement of epinephrine's vasoconstrictive effect) and insulin resistance (especially common in ectopic ACTH production), leading to hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) which can lead to diabetes mellitus. Untreated Cushing's syndrome can lead to heart disease and increased mortality. Cushing's syndrome due to excess ACTH may also result in hyperpigmentation. This is due to Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone production as a byproduct of ACTH synthesis from Proopiomelanocortin (POMC). Cortisol can also exhibit mineralcorticoid activity in high concentrations, worsening the hypertension and leading to hypokalemia (common in ectopic ACTH secretion). Furthermore, gastrointestinal disturbances, opportunistic infections and impaired wound healing (cortisol is a stress hormone, so it depresses the immune and inflammatory responses). Osteoporosis is also an issue in Cushing's Syndrome since, as mentioned before, cortisol evokes a stress-like response. The body's maintenance of bone (and other tissues) is therefore no longer one of its main priorities, so to speak. It is also important to note that Cushing's may elicit hirsutism (male-pattern hair growth in a female) and oligomenorrhea (decreased frequency of menstruation) due to elevations in androgens (male sex hormones), normally at low levels in women.

The syndrome in horses leads to weight loss, polyuria and polydipsia and may cause laminitis.

Diagnosis

When Cushing's is suspected, either a dexamethasone suppression test (administration of dexamethasone and frequent determination of cortisol and ACTH level), or a 24-hour urinary measurement for cortisol offer equal detection rates.[4] Dexamethasone is a glucocorticoid and simulates the effects of cortisol, including negative feedback on the pituitary gland. When dexamethasone is administered and a blood sample is tested, high cortisol would be indicative of Cushing's syndrome because there is an ectopic source of cortisol or ACTH (eg: adrenal adenoma) that is not inhibited by the dexamethasone. A novel approach, recently cleared by the US FDA, is sampling cortisol in saliva over 24 hours, which may be equally sensitive, as late night levels of salivary cortisol are high in Cushingoid patients. Other pituitary hormone levels may need to be ascertained. Performing a physical examination to determine any visual field defect may be necessary if a pituitary lesion is suspected, which may compress the optic chiasm causing typical bitemporal hemianopia.

When any of these tests are positive, CT scanning of the adrenal gland and MRI of the pituitary gland are performed to detect the presence of any adrenal or pituitary adenomas or incidentalomas (the incidental discovery of harmless lesions). Scintigraphy of the adrenal gland with iodocholesterol scan is occasionally necessary. Very rarely, determining the cortisol levels in various veins in the body by venous catheterization, working towards the pituitary (petrosal sinus sampling) is necessary.

Pathophysiology

Both the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland are in the brain. The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropin (ACTH). ACTH travels via the blood to the adrenal gland, where it stimulates the release of cortisol. Cortisol is secreted by the cortex of the adrenal gland from a region called the zona fasciculata in response to ACTH. Elevated levels of cortisol exert negative feedback on the pituitary, which decreases the amount of ACTH released from the pituitary gland. Strictly, Cushing's syndrome refers to excess cortisol of any etiology. One of the causes of Cushing's syndrome is a cortisol secreting adenoma in the cortex of the adrenal gland. The adenoma causes cortisol levels in the blood to be very high, and negative feedback on the pituitary from the high cortisol levels causes ACTH levels to be very low. Cushing's disease refers only to hypercortisolism secondary to excess production of ACTH from a corticotrophic pituitary adenoma. This causes the blood ACTH levels to be elevated along with cortisol from the adrenal gland. The ACTH levels remain high because a tumor causes the pituitary to be unresponsive to negative feedback from high cortisol levels.

Treatment

Most Cushing's syndrome cases are caused by steroid medications (iatrogenic). Consequently, most patients are effectively treated by carefully tapering off (and eventually stopping) the medication that causes the symptoms.

If an adrenal adenoma is identified it may be removed by surgery. An ACTH-secreting corticotrophic pituitary adenoma should be removed after diagnosis. Regardless of the adenoma's location, most patients will require steroid replacement postoperatively at least in the interim as long-term suppression of pituitary ACTH and normal adrenal tissue does not recover immediately. Clearly, if both adrenals are removed, replacement with hydrocortisone or prednisolone is imperative.

In those patients not suitable for or unwilling to undergo surgery, several drugs have been found to inhibit cortisol synthesis (e.g. ketoconazole, metyrapone) but they are of limited efficacy.

Removal of the adrenals in the absence of a known tumor is occasionally performed to eliminate the production of excess cortisol. In some occasions, this removes negative feedback from a previously occult pituitary adenoma, which starts growing rapidly and produces extreme levels of ACTH, leading to hyperpigmentation. This clinical situation is known as Nelson's syndrome.[5]

Epidemiology

Iatrogenic Cushing's (caused by treatment with corticosteroids) is the most common form of Cushing's syndrome. The incidence of pituitary tumors may be relatively high, as much as one in five people, [6] but only a minute fraction are active and produce excessive hormones.

Hyperadrenocorticism in domestic animals

Hyperadrenocorticism is a common endocrinopathy in pets. Most cases are caused by hyperplasia of the adrenal cortex in response to pituitary dysfunction. Hyperadrenocorticism in companion animals is usually treated with long term drug therapy. In dogs, treatment is accomplished with trilostane or with mitotane.[7] Dogs with pituitary-dependent Cushing's syndrome may be treated by radiation therapy directed against a pituitary adenoma. Productive adrenal tumors in dogs may be treated by non-urgent adrenalectomy.

In Equine Cushing's Syndrome, surgical treatment is impractical, and the drugs pergolide and cyproheptadine are indicated. Pergolide has been called the "treatment of choice" and improves more signs and symptoms than cyproheptadine in most studies.[8] It produces very few side effects.[9] However, cyproheptadine is still effective in some horses and is less expensive.[10]

See also

- Addison's disease

- Pseudo-Cushing's syndrome

References

- ↑ Kumar, Abbas, Fausto. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 7th ed. Elsevier-Saunders; New York, 2005.

- ↑ Cushing HW. (1932). "The basophil adenomas of the pituitary body and their clinical manifestations (pituitary basophilism).". Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 50: 137-95.

- ↑ Yudofsky, Stuart C.; Robert E. Hales (2007). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Pub, Inc.. ISBN 1585622397.

- ↑ Raff H, Findling JW (2003). "A physiologic approach to diagnosis of the Cushing syndrome". Ann. Intern. Med. 138 (12): 980–91. PMID 12809455. http://www.annals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12809455.

- ↑ Nelson DH, Meakin JW, Thorn GW (1960). "ACTH-producing pituitary tumors following adrenalectomy for Cushing's syndrome". Ann. Intern. Med. 52: 560–9. PMID 14426442.

- ↑ Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, et al (2004). "The prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a systematic review". Cancer 101 (3): 613–9. doi:. PMID 15274075.

- ↑ Nichols, Rhett. "Canine Cushing's Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment". Retrieved on 2008-02-12.

- ↑ Equine Cushing's Syndrome

- ↑ Janice Posnikoff, DVM. Advances Against Cushing’s Disease.

- ↑ Equine Marty Metzger. Cushing's Disease Often Confused with EMS. April 2008.

External links

- Cushing's Syndrome

- Cushing's Fact Sheets from The Hormone Foundation

- Cushing's syndrome

- Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service

- European Register on Cushing's Syndrome

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||