Curve

In mathematics, the concept of a curve tries to capture the intuitive idea of a geometrical one-dimensional and continuous object. A simple example is the circle. In everyday use of the term "curve", a straight line is not curved, but in mathematical parlance curves include straight lines and line segments. A large number of other curves have been studied in geometry.

This article is about the general theory. The term curve is also used in ways making it almost synonymous with mathematical function (as in learning curve), or graph of a function (Phillips curve).

Contents |

Definitions

In mathematics, a (topological) curve is defined as follows: let  be an interval of real numbers (i.e. a non-empty connected subset of

be an interval of real numbers (i.e. a non-empty connected subset of  ); then a curve

); then a curve  is a continuous mapping

is a continuous mapping  , where

, where  is a topological space. The curve

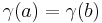

is a topological space. The curve  is said to be simple if it is injective, i.e. if for all

is said to be simple if it is injective, i.e. if for all  ,

,  in

in  , we have

, we have  . If

. If  is a closed bounded interval

is a closed bounded interval ![\,\![a, b]](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/704d2ee64df3e10003dc4da4814f13a9.png) , we also allow the possibility

, we also allow the possibility  (this convention makes it possible to talk about closed simple curve). If

(this convention makes it possible to talk about closed simple curve). If  for some

for some  (other than the extremities of

(other than the extremities of  ), then

), then  is called a double (or multiple) point of the curve.

is called a double (or multiple) point of the curve.

A curve  is said to be closed or a loop if

is said to be closed or a loop if ![\,\!I = [a,

b]](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/8afd92582f343cdfb7184389ee8e7194.png) and if

and if  . A closed curve is thus a continuous mapping of the circle

. A closed curve is thus a continuous mapping of the circle  ; a simple closed curve is also called a Jordan curve or a Jordan arc.

; a simple closed curve is also called a Jordan curve or a Jordan arc.

A plane curve is a curve for which X is the Euclidean plane — these are the examples first encountered — or in some cases the projective plane. A space curve is a curve for which X is of three dimensions, usually Euclidean space; a skew curve is a space curve which lies in no plane. These definitions also apply to algebraic curves (see below). However, in the case of algebraic curves it is very common not to restrict the curve to having points only defined over the real numbers.

This definition of curve captures our intuitive notion of a curve as a connected, continuous geometric figure that is "like" a line, without thickness and drawn without interruption, although it also includes figures that can hardly be called curves in common usage. For example, the image of a curve can cover a square in the plane (space-filling curve). The image of simple plane curve can have Hausdorff dimension bigger than one (see Koch snowflake) and even positive Lebesgue measure[1] (the last example can be obtained by small variation of the Peano curve construction). The dragon curve is another unusual example.

Conventions and terminology

The distinction between a curve and its image is important. Two distinct curves may have the same image. For example, a line segment can be traced out at different speeds, or a circle can be traversed a different number of times. Many times, however, we are just interested in the image of the curve. It is important to pay attention to context and convention in reading.

Terminology is also not uniform. Often, topologists use the term "path" for what we are calling a curve, and "curve" for what we are calling the image of a curve. The term "curve" is more common in vector calculus and differential geometry.

Lengths of curves

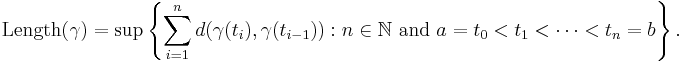

If  is a metric space with metric

is a metric space with metric  , then we can define the length of a curve

, then we can define the length of a curve ![\!\,\gamma�: [a, b] \rightarrow X](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/e07010bdfb556cbd89429f0133c643ac.png) by

by

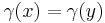

A rectifiable curve is a curve with finite length. A parametrization of  is called natural (or unit speed or parametrised by arc length) if for any

is called natural (or unit speed or parametrised by arc length) if for any  ,

,  in

in ![[a, b]](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) , we have

, we have

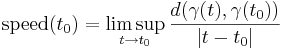

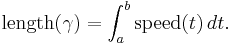

If  is a Lipschitz-continuous function, then it is automatically rectifiable. Moreover, in this case, one can define speed of

is a Lipschitz-continuous function, then it is automatically rectifiable. Moreover, in this case, one can define speed of  at

at  as

as

and then

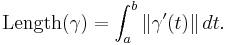

In particular, if  is Euclidean space and

is Euclidean space and ![\gamma�: [a, b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^n](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/297a5b2e872ca7032aa644fab27a1848.png) is differentiable then

is differentiable then

Differential geometry

While the first examples of curves that are met are mostly plane curves (that is, in everyday words, curved lines in two-dimensional space), there are obvious examples such as the helix which exist naturally in three dimensions. The needs of geometry, and also for example classical mechanics are to have a notion of curve in space of any number of dimensions. In general relativity, a world line is a curve in spacetime.

If  is a differentiable manifold, then we can define the notion of differentiable curve in

is a differentiable manifold, then we can define the notion of differentiable curve in  . This general idea is enough to cover many of the applications of curves in mathematics. From a local point of view one can take

. This general idea is enough to cover many of the applications of curves in mathematics. From a local point of view one can take  to be Euclidean space. On the other hand it is useful to be more general, in that (for example) it is possible to define the tangent vectors to

to be Euclidean space. On the other hand it is useful to be more general, in that (for example) it is possible to define the tangent vectors to  by means of this notion of curve.

by means of this notion of curve.

If  is a smooth manifold, a smooth curve in

is a smooth manifold, a smooth curve in  is a smooth map

is a smooth map

This is a basic notion. There are less and more restricted ideas, too. If  is a

is a  manifold (i.e., a manifold whose charts are

manifold (i.e., a manifold whose charts are  times continuously differentiable), then a

times continuously differentiable), then a  curve in

curve in  is such a curve which is only assumed to be

is such a curve which is only assumed to be  (i.e.

(i.e.  times continuously differentiable). If

times continuously differentiable). If  is an analytic manifold (i.e. infinitely differentiable and charts are expressible as power series), and

is an analytic manifold (i.e. infinitely differentiable and charts are expressible as power series), and  is an analytic map, then

is an analytic map, then  is said to be an analytic curve.

is said to be an analytic curve.

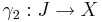

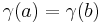

A differentiable curve is said to be regular if its derivative never vanishes. (In words, a regular curve never slows to a stop or backtracks on itself.) Two  differentiable curves

differentiable curves

and

and

are said to be equivalent if there is a bijective  map

map

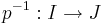

such that the inverse map

is also  , and

, and

for all  . The map

. The map  is called a reparametrisation of

is called a reparametrisation of  ; and this makes an equivalence relation on the set of all

; and this makes an equivalence relation on the set of all  differentiable curves in

differentiable curves in  . A

. A  arc is an equivalence class of

arc is an equivalence class of  curves under the relation of reparametrisation.

curves under the relation of reparametrisation.

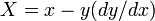

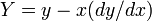

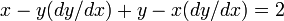

Another way to think about a curve is to look at the tangents at each point. A curve is defined by the condition that the X and Y intercepts tangents(eg. slopes) added up equals two. This can be explained using the differential equation:

Also known as point-slope form of a line, but this case we will use it to find the X and Y intercepts which are when x and y equal to 0:

Representing the condition as a differential:

Taken from text Differential Equations by Frank Ayers, Jr

Algebraic curve

Algebraic curves are the curves considered in algebraic geometry. A plane algebraic curve is the locus of points f(x, y) = 0, where f(x, y) is a polynomial in two variables defined over some field F. Algebraic geometry normally looks at such curves in the context of algebraically closed fields. If K is the algebraic closure of F, and C is a curve defined by a polynomial f(x, y) defined over F, the points of the curve defined over F, consisting of pairs (a, b) with a and b in F, can be denoted C(F); the full curve itself being C(K).

Algebraic curves can also be space curves, or curves in even higher dimensions, obtained as the intersection (common solution set) of more than one polynomial equation in more than two variables. By eliminating variables by means of the resultant, these can be reduced to plane algebraic curves, which however may introduce singularities such as cusps or double points. We may also consider these curves to have points defined in the projective plane; if f(x, y) = 0 then if x = u/w and y = v/w, and n is the total degree of f, then by expanding out wnf(u/w, v/w) = 0 we obtain g(u, v, w) = 0, where g is homogeneous of degree n. An example is the Fermat curve un + vn = wn, which has an affine form xn + yn = 1.

Important examples of algebraic curves are the conics, which are nonsingular curves of degree two and genus zero, and elliptic curves, which are nonsingular curves of genus one studied in number theory and which have important applications to cryptography. Because algebraic curves in fields of characteristic zero are most often studied over the complex numbers, algbebraic curves in algebraic geometry look like real surfaces. Looking at them projectively, if we have a nonsingular curve in n dimensions, we obtain a picture in the complex projective space of dimension n, which corresponds to a real manifold of dimension 2n, in which the curve is an embedded smooth and compact surface with a certain number of holes in it, the genus. In fact, non-singular complex projective algebraic curves are compact Riemann surfaces.

History

A curve may be a locus, or a path. That is, it may be a graphical representation of some property of points; or it may be traced out, for example by a stick in the sand on a beach. Of course if one says curved in ordinary language, it means bent (not straight), so refers to a locus. This leads to the general idea of curvature. As we now understand, after Newtonian dynamics, to follow a curved path a body must experience acceleration. Before that, the application of current ideas to (for example) the physics of Aristotle is probably anachronistic. This is important because major examples of curves are the orbits of the planets. One reason for the use of the Ptolemaic system of epicycle and deferent was the special status accorded to the circle as curve.

The conic sections had been deeply studied by Apollonius of Perga. They were applied in astronomy by Kepler. The Greek geometers had studied many other kinds of curves. One reason was their interest in geometric constructions, going beyond compass and straightedge. In that way, the intersection of curves could be used to solve some polynomial equations, such as that involved in trisecting an angle.

Newton also worked on an early example in the calculus of variations. Solutions to variational problems, such as the brachistochrone and tautochrone questions, introduced properties of curves in new ways (in this case, the cycloid). The catenary gets its name as the solution to the problem of a hanging chain, the sort of question that became routinely accessible by means of differential calculus.

In the eighteenth century came the beginnings of the theory of plane algebraic curves, in general. Newton had studied the cubic curves, in the general description of the real points into 'ovals'. The statement of Bézout's theorem showed a number of aspects which were not directly accessible to the geometry of the time, to do with singular points and complex solutions.

From the nineteenth century there is not a separate curve theory, but rather the appearance of curves as the one-dimensional aspect of projective geometry, and differential geometry; and later topology, when for example the Jordan curve theorem was understood to lie quite deep, as well as being required in complex analysis. The era of the space-filling curves finally provoked the modern definitions of curve.

See also

- Curvature

- Differential geometry of curves

- Curve orientation

- Curves in differential geometry

- List of curves

- List of curve topics

- Osculating circle

- Parametric surface

- Path (topology)

- Position vector

- Vector-valued function

Notes

- ↑ Osgood, William F. (January 1903). "A Jordan Curve of Positive Area". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society (American Mathematical Society) 4 (1): 107–112. doi:. http://www.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9947(190301)4%3A1%3C107%3AAJCOPA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-T. Retrieved on 2008-06-04.

References

- B.I. Golubov (2001), "Rectifiable curve", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1556080104

- Famous Curves Index, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland

![\mbox{length} (\gamma|_{[t_1,t_2]})=|t_2-t_1|.](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/f65f2434442cdd17b4057b2b5ee2a2d4.png)