Cuba–United States relations

|

|

|

|

| Cuba | United States |

Cuba and the United States of America have had an interest in one another since well before either of their independence movements. Plans for purchase of the nearby island have been put forward at various times by the United States. As the Spanish influence waned in the Caribbean, the United States gradually gained a position of economic and political dominance over the island, with the vast majority of foreign investment holdings, the bulk of imports and exports in its hands, and a major stake in Cuban political affairs to uphold.

Following the Cuban Revolution of 1959 relations deteriorated substantially, and have since been marked by tension and confrontation. The United States does not have formal diplomatic relations with Cuba and has maintained an embargo which makes it illegal for U.S. corporations to do business with Cuba. U.S. diplomatic representation in Cuba is handled by the United States Interests Section in Havana and a similar Cuban Interests Section remains in Washington, D.C.; both are officially part of the respective embassies of Switzerland. The United States continues to operate a naval base at Guantánamo Bay in Guantánamo Province, a point of contention between the two countries since Cuban independence in 1902.

Contents |

Historical background

Early relations

Relations between the North American mainland and the Spanish colony of Cuba began in the early 18th century through illicit commercial contracts between the European colonies of the New World, trading to elude colonial taxes. As both legal and illegal trade increased, Cuba became a comparatively prosperous trading partner in the region, and a center of tobacco and sugar production. During this period Cuban merchants increasingly traveled to North American ports, establishing trade contracts that endured for many years.

The British occupation of Havana in 1762 opened up trade with the British colonies in North America, and the rebellion of the thirteen colonies in 1776 provided additional trade opportunities. Spain opened Cuban ports to North American commerce officially in November 1776 and the island became increasingly dependent on that trade.

After the opening of the island to world trade in 1818, Cuban-United States trade agreements began to replace Spanish commercial connections. In 1820 Thomas Jefferson thought Cuba "the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States" and told Secretary of War John C. Calhoun that the United States "ought, at the first possible opportunity, to take Cuba."[1]

In a letter to U.S. Minister to Spain Hugh Nelson, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams described the likelihood of U.S. "annexation of Cuba" within half a century despite obstacles: "But there are laws of political as well as of physical gravitation; and if an apple severed by the tempest from its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union, which by the same law of nature cannot cast her off from its bosom."[2] In 1854 a secret proposal known as the Ostend Manifesto was devised by U.S. diplomats to acquire Cuba from Spain for $130 million. The manifesto was rejected due to objections from anti-slavery campaigners when the plans became public.[3]

By 1877, the United States accounted for 82 percent of Cuba's total exports, and as a monopsonist, was able to control price and hence production levels closely.[4] It was during this period that English traveller Anthony Trollope observed that "The trade of the country is falling into the hands of foreigners, Havana will soon be as American as New Orleans".[5] North Americans were also increasingly taking up residence on the island, and some districts on the northern shore were said to have more the character of America than Spanish settlements. Between 1878 and 1898 American investors took advantage of deteriorating economic conditions of the Ten Years' War to take over estates they had tried unsuccessfully to buy before while others acquired properties at very low prices.[6] Above all this presence facilitated the integration of the Cuban economy into the North American system and weakened Cuba's ties with Spain.

Independence in Cuba

- See also: Spanish-American War

As Cuban resistance to Spanish rule grew, rebels fighting for independence attempted to get support from U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant. Grant declined and the resistance was curtailed, though American interests in the region continued. US Secretary of State James G. Blaine wrote in 1881 of Cuba, "that rich island, the key to the Gulf of Mexico, and the field for our most extended trade in the Western Hemisphere, is, though in the hands of Spain, a part of the American commercial system… If ever ceasing to be Spanish, Cuba must necessarily become American and not fall under any other European domination."[7]

After some rebel successes in Cuba's second war of independence in 1897, U.S. President William McKinley offered to buy Cuba for $300 million.[8] Rejection of the offer, and an explosion that sunk the American battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor, led to the Spanish-American war. In Cuba the war became known as "the U.S. intervention in Cuba's War of Independence".[2] On 10 December 1898 Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris and, in accordance with the treaty, Spain renounced all rights to Cuba. The treaty put an end to the Spanish Empire in the Americas and marked the beginning of United States expansion and long-term political dominance in the region. Immediately after the signing of the treaty, the US-owned "Island of Cuba Real Estate Company" opened for business to sell Cuban land to Americans.[9] U.S. military rule of the island lasted until 1902 when Cuba was finally granted formal independence.

Relations 1900–1959

An agreed condition between Cuba and the United States to secure the withdrawal of United States troops from the island was Cuba's adoption of the Platt Amendment. The amendment was a rider appended to the Army Appropriations Act, a United States federal law passed in March 1901 which was presented to the U.S. Senate by Connecticut Republican Senator Orville H. Platt. The Platt amendment stipulated that the United States could exercise the right to intervene in Cuban political, economic and military affairs if necessary, and replaced the less specific Teller Amendment. It was to define the terms of Cuban-U.S. relations for the following 33 years and was bitterly resented by the majority of Cubans. Another consequence of the amendment gave the United States continued use of the southern portion of Guantánamo Bay, where a United States Naval Station had been established in 1898. The lease of the bay was confirmed by the Cuban-American Treaty which was signed by the presidents of both nations in February 1903.

Despite recognizing Cuba's transition into an independent republic, United States Governor Charles Magoon assumed temporary military rule for three more years between following a rebellion led by Jose Miguel Gomez. In 1912 U.S. forces returned again to Cuba to quell protests by Afro-Cubans against perceived discrimination. By 1926 U.S companies owned 60% of the Cuban sugar industry and imported 95% of the total Cuban crop,[10] and Washington was generally supportive of successive Cuban Governments. However, internal confrontations between the government of Gerardo Machado and political opposition led to a military overthrow by Cuban rebels in 1933. U.S. Ambassador Sumner Welles requested U.S. military intervention. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, despite his promotion of the Good Neighbor Policy toward Latin America, ordered 29 warships to Cuba and Key West, alerting United States Marines, and bombers for use if necessary. Machado's replacement, Ramón Grau assumed the Presidency and immediately nullified the Platt amendment. In protest, the United States denied recognition to Grau's government, Ambassador Welles describing the new regime as "communistic" and "irresponsible".[2][11]

The rise of General Fulgencio Batista in the 1930s to de facto leader and President of Cuba for two terms (1940-44 and 1952-59) led to an era of close co-operation between the governments of Cuba and the United States. The United States and Cuba signed the Treaty of Relations in 1934. Batista's second spell as President was initiated by a military coup planned in Florida, and U.S. President Harry S. Truman quickly recognized Batista's return to rule providing military and economic aid.[2] The Batista era witnessed the almost complete domination of Cuba's economy by the United States as the number of American corporations continued to swell, though corruption was rife and Havana also became a popular sanctuary for American organized crime figures, notably hosting the infamous Havana Conference in 1946. U.S. Ambassador to Cuba Arthur Gardner later described the relationship between the U.S. and Batista during his second spell as President:

| “ | Batista had always leaned toward the United States. I don't think we ever had a better friend. It was regrettable, like all South Americans, that he was known-although I had no absolute knowledge of it-to be getting a cut, I think is the word for it, in almost all the, things that were done. But, on the other hand, he was doing an amazing job.[12] | ” |

As armed conflict broke out in Cuba between rebels led by Fidel Castro and the Batista government, the U.S. was urged to end arms sales to Batista by Cuban president-in-waiting Manuel Urrutia. Washington made the critical move in March 1958 to prevent sales of rifles to Batista's forces, thus changing the course of the revolution irreversibly towards the rebels. The move was vehemently opposed by U.S. ambassador Earl T. Smith, and led U.S. state department advisor William Wieland to lament that "I know Batista is considered by many as a son of a bitch... but American interests come first... at least he was our son of a bitch."[13]

Post revolution relations

See also: Bay of Pigs Invasion, Cuban Missile Crisis

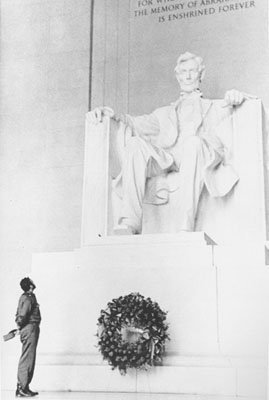

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower officially recognized the new Cuban government after the 1959 Cuban Revolution which had overthrown the Batista government, but relations between the two governments deteriorated rapidly. Within days Earl T. Smith, U.S. Ambassador to Cuba, resigned his post to be replaced by Philip Bonsal. The US government became increasingly concerned by Cuba's agrarian reforms and the nationalization of US owned industries. Between April 15 and 26th, 1959, Castro and a delegation of representatives visited the U.S. as guests of the Press Club. This visit was perceived by many as a charm offensive on the part of Castro and his recently initiated government, and his visit included laying a wreath at the Lincoln memorial. After a meeting between Fidel Castro and Vice-President Richard Nixon, where Castro outlined his reform plans for Cuba,[14] the US began to impose gradual trade restrictions on the island. On September 4 1959, Ambassador Bonsal met with Cuban Premier Fidel Castro to express “serious concern at the treatment being given to American private interests in Cuba both agriculture and utilities.”[15]

As the reforms continued, trade restrictions on Cuba increased. The U.S. stopped buying Cuban sugar and refused to supply its former trading partner with much needed oil, with a devastating effect on the island's economy. In March 1960, tensions increased when the freighter La Coubre exploded in Havana harbor, killing over 75 people. Fidel Castro blamed the United States and compared the incident to the sinking of the Maine, though admitting he could provide no evidence for his accusation.[16] That same month, President Eisenhower quietly authorized the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to organize, train, and equip Cuban refugees as a guerrilla force to overthrow Castro.[17]

Each time the Cuban government nationalized American properties, the American government took countermeasures, resulting in the prohibition of all exports to Cuba on October 19, 1960. Consequently, Cuba began to consolidate trade relations with the Soviet Union, leading the US to break off all remaining official diplomatic relations. Later that year, U.S. diplomats Edwin L. Sweet and William G. Friedman were arrested and expelled from the island having been charged with "encouraging terrorist acts, granting asylum, financing subversive publications and smuggling weapons”. On January 3, 1961 the US withdrew diplomatic recognition of the Cuban government and closed the embassy in Havana.

In 1961 Cuba resisted an armed invasion by about 1,500 CIA trained Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs.[18] President John F Kennedy's complete assumption of responsibility for the venture, which provoked a popular reaction against the invaders, proved to be a further propaganda boost for the Cuban government.[19] The U.S. began the formulation of new plans aimed at destabilizing the Cuban government. These activities were collectively known as the “The Cuban Project” (also known as Operation Mongoose). This was to be a coordinated program of political, psychological, and military sabotage, involving intelligence operations as well as assassination attempts on key political leaders. The Cuban project also proposed attacks on mainland US targets, hijackings and assaults on Cuban refugee boats to generate U.S. public support for military action against the Cuban government, these proposals were known collectively as Operation Northwoods.

A U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee report later confirmed over eight attempted plots to kill Castro between 1960 and 1965, as well as additional plans against other Cuban leaders.[20] After weathering the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba observed as U.S. armed forces staged a mock invasion of a Caribbean island in 1962 named Operation Ortsac. The purpose of the invasion was to overthrow a leader whose name, Ortsac, was Castro spelled backwards.[21] Castro soon became convinced that the U.S. was serious about invading Cuba leading to a huge military build up on the island. Tensions between the two nations reached their peak in 1962, after U.S. reconnaissance aircraft photographed the Soviet construction of intermediate-range missile sites. The discovery led to the Cuban missile crisis.

Trade relations also deteriorated in equal measure. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy broadened the partial trade restrictions imposed after the revolution by Eisenhower to a ban on all trade with Cuba, except for non-subsidized sale of foods and medicines. A year later travel and financial transactions by U.S. citizens with Cuba was prohibited. The United States embargo against Cuba was to continue in varying forms and is still in operation today. Relations began to thaw during President Lyndon B. Johnson’s tenure continuing through the next decade and a half. In 1964 Fidel Castro sent a message to Johnson encouraging dialogue, he wrote

| “ | I seriously hope that Cuba and the United States can eventually respect and negotiate our differences. I believe that there are no areas of contention between us that cannot be discussed and settled within a climate of mutual understanding. But first, of course, it is necessary to discuss our differences. I now believe that this hostility between Cuba and the United States is both unnatural and unnecessary - and it can be eliminated.[22] | ” |

Through the late 1960s and early 1970s a sustained period of aircraft hijackings between Cuba and the US by citizens of both nations led to a need for cooperation. By 1974, U.S. elected officials had begun to visit the island. Three years later, during the Carter administration, the U.S. and Cuba simultaneously opened interests sections in each other’s capitals.

In 1981 President Ronald Reagan’s new administration re-instituted the most hostile policy against Cuba since the invasion at Bay of Pigs. Despite conciliatory signals from Cuba, the administration announced a tightening of the embargo. The U.S. also re-established the travel ban, prohibiting U.S. citizens from spending money in Cuba. The ban was later supplemented to include Cuban government officials or their representatives visiting the U.S. In 1985 Radio Martí, backed by Ronald Reagan’s administration began to broadcast news and information from the U.S. to Cuba.

Veterans of CIA's 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, while no longer being sponsored by the CIA, are still in the news 46 years later. Members of Alpha 66, an anti-Castro paramilitary organization, continue to practice their AK-47 skills in a camp in South Florida.[23]

Economic sanctions against Cuba

The long standing U.S. embargo was reinforced in October 1992 by the Cuban Democracy Act (the "Torricelli Law") and in 1996 by the Cuban Liberty and Democracy Solidarity Act (known as the Helms-Burton Act). The 1992 act prohibited foreign-based subsidiaries of U.S. companies from trading with Cuba, travel to Cuba by U.S. citizens, and family remittances to Cuba. The Helms Burton Act states, among other things, that any non-U.S. company that "knowingly trafficks in property in Cuba confiscated without compensation from a U.S. person" can be subjected to litigation and that company's leadership can be barred from entry into the United States.[24] Sanctions may also be applied to non-U.S. companies trading with Cuba. As a result, multinational companies have to choose between Cuba and the U.S., the latter being a much larger market. One important exception is the German-owned delivery company DHL. This restriction also applies to maritime shipping, as ships docking at Cuban ports are not allowed to dock at U.S. ports for six months. On October 10 2006, the United States announced the creation of a task force made up of officials from several US agencies that will pursue more aggressively violators of the US trade embargo against Cuba, with penalties as severe as 10 years of prison and hundreds of dollars in fines for violators of the embargo.[25]

Recent relations

In the new millennium, hopes were raised in both countries for a new period of greater understanding. At the United Nations Millennium Summit in September 2000, Fidel Castro and US President Bill Clinton spoke briefly at a group photo session and shook hands. U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan commented afterwards, “For a U.S. president and a Cuban president to shake hands for the first time in over 40 years—I think it is a major symbolic achievement". While Castro said it was a gesture of “dignity and courtesy,” the White House denied the encounter was of any significance.[26] In November 2001 US companies began selling food to the country for the first time since Washington imposed the trade embargo after the revolution. In 2002, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter became the first former or sitting U.S. president to visit Cuba since 1928.[27]

Relations deteriorated again following the election of George W. Bush. During his campaign Bush attracted the support of Miami Cubans with anti-Castro rhetoric and ideas of tighter embargo restrictions [28] Cuban-Americans -who generally vote republican, expected effective policies and greater participation in the formation of policies regarding Cuba-US relations. [29] Approximately three months after his inauguration, the Bush administration began expanding travel restrictions. The United States Department of the Treasury issued greater efforts to deter American citizens from illegally travelling to the island. Enforcement first came in the form of sanctions that can demand up to fifty-five thousand dollars and are mailed to American citizens who are caught illegally travelling to Cuba.[30] In a 2004 meeting with members of the Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba, President Bush stated “We're not waiting for the day of Cuban freedom; we are working for the day of freedom in Cuba.”[31]. The President reaffirmed his commitment to Cuban-Americans just in time for his 2004 reelection with promises to “work” rather than wait for freedom in Cuba. Following his 2005 re-election George W. Bush declared Cuba to be one of the few "outposts of tyranny" remaining in the world. Tensions heightened as the Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security, John R. Bolton, accused Cuba of maintaining a biological weapons program..[32] Many in the US, including ex-president Carter, expressed doubts about the claim. Later, Bolton was criticised for pressuring subordinates who questioned the quality of the intelligence John Bolton had used as the basis for the assertion.[33][34] Bolton identified the Castro government as part of America's 'axis of evil', highlighting the fact that the Cuban leader visited several US foes, including Libya, Iran and Syria.[35] Cuba was also identified as a State Sponsor of Terror by the United States Department of State.[36] The Cuban government denies the claim, and in turn has accused the U.S. of engaging in state sponsored terrorism against Cuba.[37] Historian of Cuba, Wayne Smith and Anya K. Landau, write that "none of the reasons given by the Bush administration for maintaining Cuba on the terrorist list withstand the most superficial examination", and that domestic political calculations at the root of the U.S. government's position.[38]

In January 2006, United States Interests Section in Havana began displaying messages on a scrolling "electronic billboard" in the windows of their top floor. Following a protest march, the Cuban government erected a large number of poles, carrying black flags with single white stars, obscuring the messages.[39]

On September 8, 2006, it was revealed that at least ten South Florida journalists received regular payments from the U.S. government for programs on Radio Martí and TV Martí, two broadcasters aimed at undermining the Cuban government. The payments totaled thousands of dollars over several years. Those who were paid the most were veteran reporters and a freelance contributor for El Nuevo Herald, the Spanish-language newspaper published by the corporate parent of The Miami Herald. The Cuban government has long contended that some South Florida Spanish-language journalists were on the federal payroll.[40]

On September 12, 2006, the United States announced that it had created five inter agency working groups to monitor Cuba and carry out U.S. policies. The groups, some of which operate in a war-room-like setting, were quietly set up after the July 31 announcement that the ailing Cuban leader had temporarily ceded power to a collective leadership headed by his brother Raúl. U.S. officials say three of the newly created groups are headed by the State Department: diplomatic actions; strategic communications and democratic promotion. Another that coordinated humanitarian aid to Cuba is run by the Commerce Department, and a fifth, on migration issues, is run jointly by the National Security Council and the Department of Homeland Security.[41]

Recently, US Congressional auditors have accused the development agency USAID of failing properly to administer its program to allegedly promote democracy in Cuba. They said USAID had channelled tens of millions of dollars through exile groups in Miami, which were sometimes wasteful or kept questionable accounts. The report said the organizations had sent items such as chocolate and cashmere jerseys to Cuba. Their report concludes that 30% of the exile groups who received USAID grants showed questionable expenditures. [1]

Fabio Leite, director of the Radio communications Office of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), has condemned radio and television transmissions to Cuba from the United States as illegal and inadmissible and more so when they are designed to foment internal subversion on the island. The director emphasized that this constant U.S. attack is in violation of ITU regulations, which stipulate that radio transmissions within commercial broadcasting on medium wave, modulated frequency or television must be conceived of as a good quality national service within the limits of the country concerned. [2]

Current Trade relations

Under the Trade Sanctions Reform and Enhancement Act of 2000, exports from the United States to Cuba in the industries of food and medical products is permitted with the proper licensing and permissions from the U.S. Department of Commerce and the United States Department of the Treasury. The U.S. embargo on Cuba will remain in place despite Fidel Castro's announcement that he's resigning as Cuba's leader, Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte said February 19 2008.[42]

Succession issues

- See also: 2006 Cuban transfer of presidential duties

In 2003 the United States Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba was formed to "explore ways the U.S. can help hasten and ease a democratic transition in Cuba". The commission immediately announced a series of measures which included a tightening of the travel embargo to the island, a crackdown on illegal cash transfers, and a more robust information campaign aimed at Cuba.[14] Since 2005 the commission has been chaired by Condoleezza Rice and seeks to integrate the administration's Cuba policies with all the agencies of the federal government.[43] Castro has insisted that, in spite of the formation of the Commission, Cuba is itself "in transition: to socialism [and] to communism" and that it is "ridiculous for the U.S. to threaten Cuba now".[44]

In April 2006, the Bush administration appointed Caleb McCarry "transition coordinator" for Cuba, providing a budget of $59 million, with the task of promoting the governmental shift to democracy after Castro's death. Official Cuban news service Granma alleges that these transition plans were created at the behest of Cuban exile groups in Miami, and that McCarry was responsible for engineering the overthrow of the Aristide government in Haiti.[45][46] On the establishment of McCarry as post-Castro transition coordinator, Organization of American States Secretary General José Miguel Insulza said, "There's no transition and it's not your country."[47]

In 2006, The Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba released a 93-page report. The report included a plan that suggested the United States spend $80 million to overthrow the Cuban Government and ensure that Cuba's Communist system does not continue after the death of President Fidel Castro. The plan also includes a classified annex which Cuban officials claim could be a plot to assassinate Fidel Castro or a United States military invasion of Cuba.[48][49] Shortly after, The United States named a special "manager" for its intelligence operations against Cuba and Venezuela. Iran and North Korea are the only other countries that have been assigned so-called "mission managers", who supervise intelligence operations against them.

Following the temporary transfer of presidential duties in July 2006 to Raúl Castro, brother of Fidel, U.S. government figures have made a series of statements reiterating the desire for political change in Cuba. Raúl Castro responded to these statements saying: "They should be very clear that it is not possible to achieve anything in Cuba with impositions and threats. On the contrary, we have always been disposed to normalize relations on an equal plane. What we do not accept is the arrogant and interventionist policy frequently assumed by the current administration of that country."[50]

During a military parade on December 2, 2006, Raúl Castro stated; "We take this opportunity to once again state that we are willing to resolve at the negotiating table the long-standing dispute between the United States and Cuba." He said talks were only possible if the U.S. government respected Cuba's independence and did not interfere in its internal affairs. The United States, however, rejected the offer of talks, stating that "it saw no point in a dialogue with what it called the Caribbean island's "dictator-in-waiting." [3] [4]

Guantánamo Bay

- See also: Guantanamo Bay Naval Base

The US continues to operate a naval base at Guantánamo Bay. It is leased to the US and only mutual agreement or US abandonment of the area can terminate the lease. The US pays Cuba annually for its lease, but Cuba does not accept the nominal fee. The Cuban government strongly denounces the treaty on grounds that it violates article 52, titled "Coercion of a State by the threat or use of force", of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. However, Article 4, titled "Non-retroactivity of the present Convention" of the same document states that Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties shall not be retroactively applied to any treaties made before itself.[51]

The acquisition of Guantánamo Bay was part of the Platt Amendment, conditions for the withdrawal of United States troops remaining in Cuba since the Spanish-American War.

See also

- Foreign relations of Cuba

- Foreign relations of the United States

- United States-Latin American relations

External links

- BBC: Timeline: US-Cuba Relations

- Complete text of the Teller amendment

- Complete text of the Platt amendment

- U.S. Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba

- US Judiciary Hearings of Communist Threats to America Through the Caribbean

- U.S.-Cuban Relations: An Analytic Compendium of U.S. Policies, Laws & Regulations – Occasional Paper (March 2005) by Dianne E. Rennack and Mark P. Sullivan from the Atlantic Council of the US.

- The Cuban Rafter Phenomenon: A Unique Sea Exodus

- The Candidates on Cuba Policy-- Council on Foreign Relations

References

- ↑ The American Empire Not So Fast Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. World Policy Journal

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Cuba and the United States : A chronological History Jane Franklin

- ↑ Hugh Thomas. Cuba : The pursuit for freedom. p.134-5

- ↑ Bakewell, Peter. A History of Latin America. Blackwell publishers. p454.

- ↑ Perez, Jr, Louis A (March 6 2001). "On Becoming Cuban". HarperCollins.

- ↑ The Cuban Sugar industry José Alvarez

- ↑ Sierra, J.A.. "José Martí: Apostle of Cuban Independence". historyofcuba.com. Retrieved on 2006-07-07.

- ↑ Cuba: Revolution, Resistance And Globalisation James Ferguson 2004

- ↑ Struggle for Independence J.A, Sierra

- ↑ Hugh Thomas. Cuba : The pursuit for freedom. p.336

- ↑ Timetable History of Cuba J.A. Sierra

- ↑ Hearings to the Sub Committee 1960

- ↑ Hugh Thomas. Cuba : The pursuit for freedom. p.650

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Timeline: US-Cuba relations BBC

- ↑ Department of State Cable Ambassador Report on Meeting With Castro, September 4 1959

- ↑ Fursenko and Naftali, The Cuban Missile Crisis. p40-47

- ↑ Bay of Pigs Global Security.org

- ↑ Castro marks Bay of Pigs victory BBC News

- ↑ Angelo Trento. Castro and Cuba : From the revolution to the present. Arris books. 2005.

- ↑ Interim Report: Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders Original document

- ↑ Profile in Courage New York Times. June 8, 2003.

- ↑ Message from Castro to US President Lyndon B. Johnson, 1964 Declassified document

- ↑ "The coddled "terrorists" of South Florida" by Tristram Korten and Kirk Nielsen, Salon.com, January 14, 2008

- ↑ Full text of Cuban Liberty and Democracy Solidarity Act

- ↑ "US tightens Cuba embargo enforcement". TurkishPress.com (October 10 2006). Retrieved on 2006-10-22.

- ↑ The earth-shattering, delightful Clinton-Castro handshake World Tribune.com

- ↑ The Carter Center, "Activities by Country: Cuba", http://www.cartercenter.org/countries/cuba.html, retrieved on 2008-07-17

- ↑ Perez, Louis A. Cuba: Between Reform And Revolution, New York, NY. 2006, p326

- ↑ Perez, Louis A. Cuba: Between Reform And Revolution, New York, NY. 2006, p326

- ↑ Cuba vs. Blockade. www.cubavsbloqueo.cu

- ↑ Lobe, Jim. Bush Tightens Cuba Embargo. Available at www.antiwar.com/lobe

- ↑ Bolton articleNews Max

- ↑ Bolton faces tough questioning from DemocratsMcClatchy Newspapers

- ↑ Cuba sharing bioweapons technology CNN

- ↑ US and Cuba's complex relations BBC

- ↑ United States Department of State Report

- ↑ The United States is an accomplice and protector of terrorism, states Alarcón Granma International

- ↑ http://ciponline.org/cuba/cubaandterrorism/CubaontheTerroristList.pdf

- ↑ US Havana messages outrage Castro BBC January 23, 2006

- ↑ 10 Miami journalists take U.S. pay Miami Herald September 8 2006

- ↑ Bachelet, Pablo (September 13 2006). "U.S. creates five groups to monitor Cuba". MiamiHerald.com. Retrieved on 2006-10-22.

- ↑ CNN - Castro's resignation won't change U.S. policy, official says

- ↑ Associated Press. Condi Rice Chairs Anti-Castro Panel. NewsMax.com Wires, December 20, 2005

- ↑ Rigoberto Diaz. Castro Calls Rice 'Mad'. News24, December 24, 2005

- ↑ planning for - the succession BBC

- ↑ GRANMA

- ↑ Miami Herald OAS leader charts an independent course

- ↑ New Zealand News

- ↑ CBS News

- ↑ Raul Castro Comments on Cuba-U.S. Ties Guardian unlimited

- ↑ http://untreaty.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf pdf

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||