Creek (people)

| Creek |

|---|

|

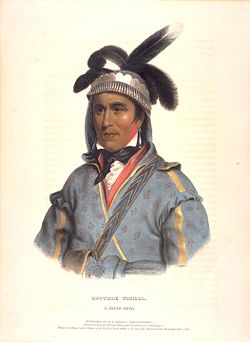

| Opothleyahola, Muscogee Creek Chief, 1830s |

| Total population |

|

50,000-60,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Oklahoma, Alabama) |

| Languages |

| English, Creek |

| Religion |

| Protestantism, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Muskogean peoples: Alabama, Coushatta, Miccosukee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole |

The Creek are an American Indian people originally from the southeastern United States, also known by their original name Muscogee (or Muskogee), the name they use to identify themselves today.[1] Mvskoke is their name in traditional spelling. Modern Muscogees live primarily in Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. Their language, Mvskoke, is a member of the Creek branch of the Muskogean language family. The Seminole are close kin to the Muscogee and speak a Creek language as well. The Creeks were considered one of the Five Civilized Tribes.

Contents[hide] |

History

The early historic Creeks were probably descendants of the mound builders of the Mississippian culture along the Tennessee River in modern Tennessee[2] and Alabama, and possibly related to the Utinahica of southern Georgia. More of a loose confederacy than a single tribe, the Muscogee lived in autonomous villages in river valleys throughout what are today the states of Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama and consisted of many ethnic groups speaking several distinct languages, such as the Hitchiti, Alabama, and Coushatta. Those who lived along the Ocmulgee River were called "Creek Indians" by British traders from South Carolina. Eventually the name was applied to all of the various inhabitants of Creek towns, which were divided into the Lower Towns of the Georgia frontier on the Chattahoochee River, Ocmulgee River, and Flint River, and the Upper Towns of the Alabama River Valley.

The Lower Towns included Coweta, Cusseta (Kasihta, Cofitachiqui), Upper Chehaw (Chiaha), Hitchiti, Oconee, Ocmulgee, Okawaigi, Apalachee, Yamasee (Altamaha), Ocfuskee, Sawokli, and Tamali. The Upper Towns included Tuckabatchee, Abhika, Coosa (Kusa; the dominant people of East Tennessee and North Georgia during the Spanish explorations), Itawa (original inhabitants of the Etowah Indian Mounds), Hothliwahi (Ullibahali), Hilibi, Eufaula, Wakokai, Atasi, Alibamu, Coushatta (Koasati; they had absorbed the Kaski/Casqui and the Tali), and Tuskegee ("Napochi" in the de Luna chronicles).

Cusseta (Kasihta) and Coweta are still the two principal towns of the Creek Nation. Traditionally, the Cusseta and Coweta bands are considered the earliest members of the Creek Nation.[1]

Revolutionary War era

Like many Native American groups east of the Mississippi and Louisiana Rivers, the Creeks were divided in the American Revolutionary War. The Lower Creeks remained neutral; the Upper Creeks allied with the British and fought the American Patriots.

After the war ended in 1783, the Creeks discovered that Britain had ceded Creek lands to the now independent United States. Georgia began to expand into Creek territory. Creek statesman Alexander McGillivray rose to prominence as he organized pan-Indian resistance to this encroachment and received arms from the Spanish in Florida to fight trespassers. McGillivray worked to create a sense of Creek nationalism and centralize Creek authority. He struggled against village leaders who individually sold land to the United States. By the Treaty of New York in 1790, McGillivray ceded a significant portion of the Creek lands to the United States under President George Washington in return for federal recognition of Creek sovereignty within the remainder. McGillivray died in 1793, however, and Georgia continued to expand into Creek territory.

In 1799 English adventurer William Augustus Bowles was elected director general of the State of Muskogee by a congress of Creeks and Seminoles.As both Spain and the USA claimed the land, Bowles hoped to be able to create an independent Creek nation, the State of Muskogee.

First to Civilize

George Washington, the first U.S. President, and Henry Knox, the first U.S. Secretary of War, proposed a cultural transformation of the Native Americans.[3] Washington believed that Native Americans were equals, but that their society was inferior. He formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process, and it was continued under President Thomas Jefferson.[4] Noted historian Robert Remini wrote "they presumed that once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans."[5] Washington's six-point plan included impartial justice toward Indians; regulated buying of Indian lands; promotion of commerce; promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Indian society; presidential authority to give presents; and punishing those who violated Indian rights.[6] The Creeks would be the first Native Americans to be civilized under Washington's six-point plan. The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole would follow the Creeks efforts to benefit under Washington's new policy of civilization.

In 1796, Washington appointed Benjamin Hawkins as General Superintendent of Indian Affairs dealing with all tribes south of the Ohio River. He personally assumed the role of principal agent to the Creeks. He moved to the area that is now Crawford County in Georgia. He began to teach agricultural practices to the tribe, starting a farm at his home on the Flint River. In time, he brought in slaves and workers, cleared several hundred acres and established mills and a trading post as well as his farm.

For years, he would meet with chiefs on his porch and discuss matters. He was responsible for the longest period of peace between the settlers and the tribe, overseeing 19 years of peace. When a fort was built, in 1806, to protect expanding settlements, just east of modern Macon, Georgia, it was named Fort Benjamin Hawkins.

Hawkins was dis-heartened and shocked with the Creek War which destroyed his life work of improving Creek Native Americans quality of life. Hawkins saw much of his work toward building a peace destroyed in 1812. A group of Creeks, led by Tecumseh were encouraged by British agents to resistance against increasing settlement by whites. Although he personally was never attacked, he was forced to watch an internal civil war among the Creeks, the war with a faction known as the Red Sticks, and their eventual defeat by Andrew Jackson.

Red Stick War

The Creek War of 1813-1814, also known as the Red Stick War, began as a civil war within the Creek Nation, only to become enmeshed within the War of 1812. Inspired by the fiery eloquence of the Shawnee leader Tecumseh and their own religious leaders, Creeks from the Upper Towns, known to the Americans as Red Sticks, sought to aggressively resist white immigration and the "civilizing programs" administered by U.S. Indian Agent Benjamin Hawkins. Red Stick leaders William Weatherford (Red Eagle), Peter McQueen and Menawa violently clashed with the Lower Creeks led by William McIntosh, who were allied with the Americans.

On August 30, 1813, Red Sticks led by Red Eagle attacked the American outpost of Fort Mims near Mobile, Alabama, where white settlers and their Indian allies had gathered. The Red Sticks captured the fort by surprise, and a massacre ensued, as prisoners — including women and children — were killed. Nearly 250 died, and panic spread across the American southwestern frontier.

Tennessee, Georgia, and the Mississippi Territory sent militia units deep into Creek territory. Although outnumbered and poorly armed, the Red Sticks put up a desperate fight from their strongholds. On March 27, 1814, General Andrew Jackson's Tennessee militia, aided by the 39th U. S. Infantry Regiment plus Cherokee and Creek allies, finally crushed Red Stick at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on the Tallapoosa River.

Though the Red Sticks had been soundly defeated and about 3,000 Upper Creeks died in the war, the remnants held out several months longer. In August 1814, exhausted and starving, they surrendered to Jackson at Wetumpka (near the present city of Montgomery, Alabama). On August 9, 1814, the Creek nation was forced to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which ended the war and required them to cede some 20 million acres (81,000 km²) of land—more than half of their ancestral territorial holdings—to the United States. Even those who had fought alongside Jackson were compelled to cede land, since Jackson held them responsible for allowing the Red Sticks to revolt. The state of Alabama was carved largely out of their domain and was admitted to the United States in 1819.

Many Creeks refused to surrender and escaped to Florida. Some allied themselves with Florida Indians (who eventually become collectively called the Seminoles) and the British against the Americans. They were involved on both sides of the Seminole War in Florida.

Present

Most Muscogees were removed to Indian Territory during the Trail of Tears in 1834, although some remained behind. There are Muscogees in Alabama living near Poarch Creek Reservation in Atmore (northeast of Mobile), as well as Creeks in essentially undocumented ethnic towns in Florida. The Alabama reservation includes a casino and 16 story hotel and holds an annual powwow on Thanksgiving. Additionally, Muscogee descendants of varying degrees of acculturation live throughout the southeastern United States. The tribal government operates a budget in excess of $106 million, has over 2,400 employees, and maintains tribal facilities and programs in eight administrative districts. The nation operates several significant tribal enterprises, including the Muscogee Document Imaging Company; travel plazas in Okmulgee, Muskogee and Cromwell, Oklahoma; construction, technology and staffing services; and major casinos in Tulsa and Okmulgee. The tribal population is fully integrated into the larger culture and economy of Oklahoma, with Muscogee Nation citizens making significant contributions in every field of endeavor, while continuing to preserve and share a vibrant tribal identity through events such as annual festivals, ball-games, and language classes. The Stomp Dance and Green Corn Ceremony are both highly revered gatherings and rituals that have largely remained non public and not by coincidence "Pure". The Nation's historic old Council House, built in 1878 and located in downtown Okmulgee, was completely restored in the 1990s and now serves as a museum of tribal history.

Famous Creek

- Christopher Rolin Ghost Recon Champion

- Lt. Col. Ernest Childers, First American Indian to Receive World War II Congressional Medal of Honor[1]

- William McIntosh, Lower Creek Mico [2] [3]

- Acee Blue Eagle, artist.

- Johnnie Diacon, artist, Thlopthlocco Tribal Town (Raprakko Etvlwv), Deer Clan (Ecovlke).

- Joy Harjo, Native American poet.

- Retha Gambaro, artist.

- Suzan Shown Harjo

- Jim Pepper, jazz musician.

- Will Sampson, film actor, noted for his performance in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975).

- France Winddance Twine, American sociologist, feminist and race theorist.

- Synyster Gates, lead guitar player from the band Avenged sevenfold has Creek ancestry.

- Frank Van Zant, who also went by the name Chief Rolling Mountain Thunder. He built and lived in the Thunder Mountain Indian Monument in Imlay, Nevada.[7]

- Jack Jacobs, football player

- James McHenry, Confederate Major, Methodist minister, and important Creek leader

- Cynthia Leitich Smith, Children's book author noted for "Jingle Dancer"

- Thomas Francis Meagher, Jr. (cousin of Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher) Creek Historian, Rough Rider

- Micah Ian Wright, film, television & videogame writer, chair of the Writers Guild of America's American Indian Writers Committee.

- Carrie Underwood, country singer.

- William Harjo LoneFight, noted Native American author, entrepreneur and nationally known expert in the revitalization of Native American Languages and Cultural Traditions.

See also

- Cherokee Indians

- African-Native Americans

- Creek language

- Creek mythology

- Native American tribe

- Native Americans in the United States

- Gallery of Native Americans with facial hair

- Ocmulgee National Monument

- One-Drop Rule

- Opothleyahola

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Transcribed documents Sequoyah Research Center and the American Native Press Archives

- ↑ Finger, John R. (2001). Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Indiana University Press. pp. p. 19. ISBN 0-253-33985-5.

- ↑ Perdue, Theda. "Chapter 2 "Both White and Red"". Mixed Blood Indians: Racial Construction in the Early South. The University of Georgia Press. p. 51. ISBN 082032731X.

- ↑ Remini, Robert. ""The Reform Begins"". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 201. ISBN 0965063107.

- ↑ Remini, Robert. ""Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit"". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 258. ISBN 0965063107.

- ↑ Miller, Eric (1994). "George Washington And Indians" (HTML). Eric Miller. Retrieved on 2008-05-02.

- ↑ Background of Thunder Mountain Monument, thundermountainmonument.com, Retrieved on 2007-11-26.

Suggested Media

- First Frontier, Docu-drama, Auburn University Educational Television, 1987. The docu-drama covers the encounter with Hernando DeSoto to the era of Indian Removal; the film focuses on the Creek peoples.

- Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. Robbie Ethridge, 2003, The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0807854956

References

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland (1993). Deerskins & Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685-1815. Indians of the Southeast. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. OCLC 45732303.

- Jackson, Harvey H. III (1995). Rivers of History-Life on the Coosa, Tallapoosa, Cahaba and Alabama''. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817307710.

- Swanton, John R. (1922). Early History of the Creek Indians and their Neighbors. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 18032096.

- Swanton, John R. (1928). "Social Organization and the Social Usages of the Indians of the Creek Confederacy". Forty-Second Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. pp. 23-472. OCLC 14980706.

- Walker, Willard B. (2004). "Creek Confederacy Before Removal". in Raymond D. Fogelson (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 14: Southeast. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 373-392. OCLC 57192264.

- Worth, John E. (2000). "The Lower Creeks: Origins and Early History". in Bonnie G. McEwan (ed.). Indians of the Greater Southeast: Historical Archaeology and Ethnohistory. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. pp. 265-298. OCLC 49414753.

External links

- Perdido Bay Tribe of Creek Indians

- Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma (official site)

- Creek Nation Indian Territory Project

- LostWorlds.org | Ocmulgee Mounds: Creek/Muskogee Origins

- Creek (Muskogee) by Kenneth W. McIntosh -- Encyclopedia of North American Indians

- History of the Creek Indians in Georgia

- Poarch Creek Indians in Alabama

- Poarch Band of Creek Indians

- Comprehensive Creek Language materials online

- Southeastern Native American Documents, 1763-1842.

- New Georgia Encyclopedia entry

- Encyclopedia of Alabama article

- Lewis and James McHenry

- "Fife Family Cemetery," Southern Spaces -- a short film on Creek Christian burial practices

|

|||||