Crater Lake National Park

| Crater Lake National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

|

|

| Location | southwestern Oregon, USA |

| Nearest city | Medford |

| Coordinates | [1] |

| Area | 183,224 acres (74,148 ha) |

| Established | May 22, 1902 |

| Visitors | 388,972 (in 2006) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

Crater Lake National Park is a United States National Park located in Southern Oregon whose primary feature is Crater Lake. It was established on May 22,1902, as the sixth National Park in the U.S.[2] The park encompasses Crater Lake's caldera, which rests in the remains of a destroyed volcano posthumously called Mount Mazama. It is the only National Park in Oregon.

The lake is 1,949 feet (594 m) deep at its deepest point which makes it the deepest lake in the United States, second in North America, and according to Wikipedia's list of lakes by depth, the ninth deepest anywhere in the world.[note 1] However, when comparing its average depth of 1,148 feet (350 m) to the average depth of other deep lakes, Crater Lake becomes the deepest in the Western Hemisphere and the third deepest in the world. The impressive average depth of this volcanic lake is due to the nearly symmetrical 4,000-foot (1,200 m) deep caldera formed 7,700 years ago during the violent climactic eruptions and subsequent collapse of Mt. Mazama and the relatively moist climate that is typical of the crest of the Cascade Mountains.

The caldera rim ranges in elevation from 7,000 to 8,000 feet (2,100 to 2,400 m). The USGS benchmarked elevation of the lake surface itself is 6,178 feet (1,883 m). The park covers 286 square miles (741 km2). Crater Lake has no streams flowing into or out of it. The lake's water regularly has a striking blue hue and is filled entirely from direct precipitation in the form of snow and rain. All water that enters the lake is eventually lost from evaporation or subsurface seepage.

Contents |

Geology

-

For more details on this topic, see Mount Mazama.

Volcanic activity in the area is fed by subduction off the coast of Oregon as the Juan de Fuca Plate slips below the North American Plate (see plate tectonics). Heat and compression generated by this movement has created a mountain chain topped by a series of volcanoes, which together are called the Cascade Range. The large volcanoes in the range are called the High Cascades. However, there are many other volcanoes in the range as well, most of which are much smaller.

About 400,000 years ago, Mount Mazama began life in much the same way as the other mountains of the High Cascades, as overlapping shield volcanoes. Over time, alternating layers of lava flows and pyroclastic flows built Mazama's overlapping cones until it reached about 11,000 feet (3,400 m) in height.

As the young stratovolcano grew, many smaller volcanoes and volcanic vents were built in the area of the park and just outside what are now the park's borders. Chief among these were cinder cones. Although the early examples are gone—cinder cones erode easily—there are at least 13 much younger cinder cones in the park, and at least another 11 or so outside its borders, that still retain their distinctive cinder cone appearance. There continues to be debate as to whether these minor volcanoes and vents were parasitic to Mazama's magma chamber and system or if they were related to background Oregon Cascade volcanism.

After a period of dormancy, Mazama became active again. Then, around 5700 BC, Mazama collapsed into itself during a tremendous volcanic eruption, losing 2,500 to 3,500 feet (760 to 1,100 m) in height. The eruption formed a large caldera that, depending on the prevailing climate, was filled in about 740 years, forming a beautiful lake with a deep blue hue, known today as Crater Lake.[3]

The eruptive period that decapitated Mazama also laid waste to much of the greater Crater Lake area and deposited ash as far east as the northwest corner of what is now Yellowstone National Park, as far south as central Nevada, and as far north as southern British Columbia. It produced more than 150 times as much ash as the May 181980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

This ash has since developed a soil type called andisol. Soils in Crater Lake National Park are brown, dark brown or dark grayish brown sandy loams or loamy sands which have plentiful cobbles, gravel and stones. They are slightly to moderately acidic and their drainage is somewhat excessive or excessive.

Park features

Some notable park features created by this huge eruption are:

- The Pumice Desert: A very thick layer of pumice and ash leading away from Mazama in a northerly direction. Even after thousands of years, this area is largely devoid of plants due to excessive porosity (meaning water drains through quickly) and poor soil composed primarily of regolith.

- The Pinnacles: When the very hot ash and pumice came to rest near the volcano, it formed 200-to-300-foot (60 to 90 m) thick gas-charged deposits. For perhaps years afterward, hot gas moved to the surface and slowly cemented ash and pumice together in channels and escaped through fumaroles. Erosion later removed most of the surrounding loose ash and pumice, leaving tall pinnacles and spires.

- Other park features

- Mount Scott is a steep andesitic cone whose lava came from magma from Mazama's magma chamber; geologists call such volcano a "parasitic" or "satellite" cone. Volcanic eruptions apparently ceased on Scott sometime before the end of the Pleistocene; one remaining large cirque on Scott's northwest side was left unmodified by post-ice age volcanism.

- In the southwest corner of the park stands Union Peak, an extinct volcano whose primary remains consist of a large volcanic plug, which is lava that solidified in the volcano's neck.

- Crater Peak is a shield volcano primarily made of andesite and basalt lava flows topped by andesitic and dacite tephra.

- Timber Crater is a shield volcano located in the northeast corner of the park. Like Crater Peak, it is made of basaltic and andesitic lava flows, but, unlike Crater, it is topped by two cinder cones.

- Rim Drive is the most popular road in the park; it follows a scenic route around the caldera rim.

- The Pacific Crest Trail, a 2,650-mile (4,260 km) long distance hiking and equestrian trail that stretches from the Mexican to Canadian borders, passes through the park.

History

Local Native Americans witnessed the collapse of Mount Mazama and kept the event alive in their legends. One ancient legend of the Klamath people closely parallels the geologic story which emerges from today's scientific research. The legend tells of two Chiefs, Llao of the Below World and Skell of the Above World, pitted in a battle which ended up in the destruction of Llao's home, Mt. Mazama.[4] The battle was witnessed in the eruption of Mt. Mazama and the creation of Crater Lake.

The first known European Americans to visit the lake were a trio of gold prospectors: John Wesley Hillman, Henry Klippel, and Isaac Skeeters who, on June 12, 1853, stumbled upon the long, sloping mountain while looking for a lost mine. Stunned by vibrant blue color of the lake, they named the indigo body of water "Deep Blue Lake" and the place on the southwest side of the rim where he first saw the lake later became known as Discovery Point.[2] But gold was more on the minds of settlers at the time and the discovery was soon forgotten. The suggested name later fell out of favor by locals, who preferred the name Crater Lake.

William Gladstone Steel devoted his life and fortune to the establishment and management of a National Park at Crater Lake. His preoccupation with the lake began in 1870. In his efforts to bring recognition to the park, he participated in lake surveys that provided scientific support. He named many of the lake's landmarks, including Wizard Island, Llao Rock, and Skell Head.

With the help of geologist Clarence Dutton, Steel organized a USGS expedition to study the lake in 1886. The party carried the Cleetwood, a half-ton survey boat, up the steep slopes of the mountain then lowered it to the lake. From the stern of the Cleetwood, a piece of pipe on the end of a spool of piano wire sounded the depth of the lake at 168 different points. Their deepest sounding, 1,996 feet (608 m), was very close to the modern official depth of 1,932 feet (589 m) made in 1953 by sonar.[2] At the same time, a topographer surveyed the area and created the first professional map of the Crater Lake area.

Partly based on data from the expedition and lobbying from Steel and others, Crater Lake National Park was established May 22, 1902 by President Theodore Roosevelt. And because of Steel's involvement, Crater Lake Lodge was opened in 1915 and the Rim Drive was completed in 1918.[2]

Highways were later built to the park to help facilitate tourism. The 1929 edition of O Ranger! described access and facilities available by then:

| “ | Crater Lake National Park is reached by train on the Southern Pacific Railroad lines into Medford and Klamath Falls, at which stops motor stages make the short trip to the park. A hotel on the rim of the lake offers accommodations. For the motorist, the visit to the park is a short side trip from the Pacific and Dalles-California highways. He will find, in addition to the hotel, campsites, stores, filling stations. The park is open to travel from late June or July 1 for as long as snow does not block the roads, generally until October.[5] | ” |

Activities

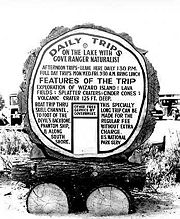

There are many hiking trails inside the park, and several campgrounds. Unlicensed fishing is allowed without limitation of size, species or number. The lake is believed to have no indigenous fish, but were introduced beginning in 1888 until fish stocking ended in 1941. Kokanee Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) and Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) now thrive naturally.[6] Swimming is allowed in the lake, and boat tours, which stop at Wizard Island a cinder cone inside the lake, operate daily during the summer. All lake access is from Cleatwood Trail, a steep walking trail.

Observation points along the caldera rim are easily accessible by car via Rim Drive, which is 33 miles (53 km) long and has an elevation gain of 3,800 feet (1,200 m).

The highest point in the park is Mt. Scott at 8,929 feet (2,722 m). Getting there requires a fairly steep 2.5-mile (4.0 km) hike from the Rim Drive trailhead. On a clear day visibility from the summit exceeds 100 miles (160 km) and can, in one single view, take in the entire caldera. Also visible from this point are white peaked High Cascade volcanoes to the north, the Columbia River Plateau to the east, and the Western Cascades and the more distant Klamath Mountains to the west.

Crater Lake's features are fully accessible during the summer months: heavy snow in the park during the fall, winter, and spring forces road and trail closures, including popular Rim Drive (which is generally open from July to October).

See also

- Crater Lake - More information about the lake

- Crater Lake Lodge - More information about the lodge

- Mount Mazama - Formation of the volcano and its collapse to form the lake more than 7000 years ago

- List of nationally protected areas of the United States

- National Park Service Rustic about the architecture of the park structures

- Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway

Notes

- ↑ Crater Lake is often referred to as the seventh deepest lake in the world, but this former listing excludes the approximately 3,000 feet (910 m) depth of subglacial Lake Vostok in Antarctica, which resides under nearly 13,000 feet (4,000 m) of ice, and the recent report of a 2,740 feet (840 m) maximum depth for Lake O'Higgins/San Martin, located on the border of Chile and Argentina

References

- ↑ "Crater Lake National Park". Geographic Names Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Crater Lake". National Park Service. Retrieved on 2006-08-18.

- ↑ Manuel Nathenson; Charles R. Bacon, David W. Ramsey (2007). "Subaqueous geology and a filling model for Crater Lake, Oregon". Hydrobiologia vol. 574: pp. 13–27. doi:.

- ↑ "Park History". National Parks Service. Retrieved on 2006-08-18.

- ↑ Albright, Horace M.; Frank J. Taylor. Oh, Ranger!. illustrated by Ruth Taylor White (Centennial ed.). Riverside, Connecticut: The Chatham Press, Inc.. http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/albright3/chap13a.htm. Retrieved on 2006-08-18.

- ↑ "Fish and Fishing at Crater Lake National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved on 2006-08-18.

- Harmon, Rick (2002). Crater Lake National Park: A History. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 0-87071-537-2.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1988). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-220-X.

- Harris, Ann G.; Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D. Tuttle (1997). Geology of National Parks (Fifth Edition ed.). Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 0-7872-5353-7.

- Charles R., Bacon; James V. Gardner, Larry A. Mayer, Mark W. Buktenica, Peter Darnell, David W. Ramsey, Joel E. Robinson (June 2002). "Morphology, volcanism, and mass wasting in Crater Lake, Oregon". Geological Society of America Bulletin vol. 114 (no. 6): pp. 675-692.

External links

- "Crater Lake National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

- "Crater Lake, Oregon". Earth Observatory. NASA. Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

- "Crater Lake National Park Trust". Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||