Counterfeit

A counterfeit is an imitation that is made usually with the intent to deceptively represent its content or origins. The word counterfeit most frequently describes forgeries of currency or documents, but can also describe clothing, software, pharmaceuticals, watches, or more recently, cars and motorcycles, especially when this results in patent infringement or trademark infringement.

Contents |

Counterfeiting of money

- See also: Coin counterfeiting and Slug (coin)

History

Counterfeiting is probably as old as money itself. Before the introduction of paper money, the main way of doing it was to mix base metals in what was supposed to be pure gold or silver. Also, individuals would "shave" the edges of a coin so that it weighed less than it was supposed to, a process known as clipping. This is not counterfeiting but the exponents could use the precious metal clippings to make counterfeits. A fourrée is an ancient type of counterfeit coin, in which a base metal core has been plated with a precious metal to look like its solid metal counter part.

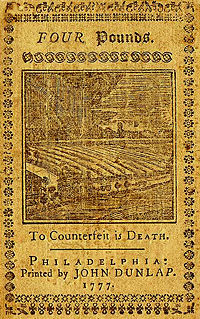

Kings often dealt very harshly with the perpetrators of such deeds. In 1162, Emperor Gaozong of Song had promulgated a decree to punish the counterfeiter of Huizi to death and to reward the informant.[1] The English couple Thomas Rogers and Anne Rogers were convicted on 15 October 1690 for "Clipping 40 pieces of Silver" (in other words, clipping the edges off silver coins). Thomas Rogers was hanged, drawn and quartered and Anne Rogers was burnt alive. The gruesome forms of punishment were due to the two's acts being construed as "treason", rather than simple crime. In America, counterfeiting also used to be punishable by death; for example, paper currency printed by Benjamin Franklin often bore the phrase "to counterfeit is death."[2] The theory behind such harsh punishments was that one who had the skills to counterfeit currency was considered a threat to the safety of the state, and had to be eliminated - another explanation is the fact that issuing money that people could trust was both an economic imperative, as well as a (where applicable) royal prerogative - therefore counterfeiting was a crime against the state or ruler itself, rather than against the person who received the fake money.

Far more fortunate was an earlier practitioner of the same art, active in the time of the Emperor Justinian, who got the nickname Alexander the Barber. Rather than being executed, when he was caught the Emperor decided to employ his financial talents in the government's own service.

Modern counterfeiting begins with paper money. Nations have used counterfeiting as a means of warfare. The idea is to overflow the enemy's economy with fake bank notes, so that the real value of the money plummets. Great Britain did this during the Revolutionary War to reduce the value of the Continental Dollar. Although this tactic was also employed by the United States during the American Civil War, the fake Confederate currency it produced was of superior quality to the real thing.

Instances

A form of counterfeiting is the production of documents by legitimate printers in response to fraudulent instructions. An example of this is the Portuguese Bank Note Crisis of 1925, when the British banknote printers Waterlow and Sons produced Banco de Portugal notes equivalent in value to 0.88% of the Portuguese nominal Gross Domestic Product, with identical serial numbers to existing banknotes, in response to a fraud perpetrated by Alves dos Reis. Similarly, in 1929 the issue of postage stamps celebrating the Millennium of Iceland's parliament, the Althing, was compromised by the insertion of "1" on the print order, before the authorised value of stamps to be produced (see Postage stamps and postal history of Iceland.)

In 1926 a high-profile counterfeit scandal came to light in Hungary, when several people were arrested in the Netherlands while attempting to procure 10 million francs worth of fake French 1000-franc bills which had been produced in Hungary; after 3 years, the state-sponsored industrial scale counterfeit operation had finally collapsed. The League of Nations' investigation found Hungary's motives were to avenge its post-WWI territorial losses (blamed on Georges Clemenceau) and to use profits from the counterfeiting business to boost a militarist, border-revisionist ideology. Germany and Austria had an active role in the conspiracy, which required special machinery. The quality of fake bills was still substandard however, due to France's use of exotic raw paper material imported from its colonies.

During World War II, the Nazis attempted to do a similar thing to the Allies with Operation Bernhard. The Nazis took Jewish artists in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and forced them to forge British pounds and American dollars. The quality of the counterfeiting was very good, and it was almost impossible to distinguish between the real and fake bills. The Germans could not put their plan into action, and were forced to dump the counterfeit bills into a lake. The bills were not recovered until the 1950s.[3]

Today the finest counterfeit banknotes are claimed to be U.S. dollar bills produced in North Korea, which are used to finance the North Korean government, among other uses. The fake North Korean copies are called Superdollars because of their high quality. Bulgaria and Colombia are also significant sources of counterfeit currency. Recently, on May 23rd, 2007, the Swiss government has raised some doubt as to the ability of North Korea to produce the "Superdollars".

There has been a rapid growth in the counterfeiting of Euro banknotes and coins since the launch of the currency in 2002. In 2003, 551,287 fake euro notes and 26,191 bogus euro coins were removed from EU circulation. In 2004, French police seized fake 10 euro and 20 euro notes worth a total of around €1.8 million from two laboratories and estimated that 145,000 notes had already entered circulation.

In the early years of the 21st century, the United States Secret Service has noted a substantial reduction in the quantity of forged U.S. currency, as counterfeiters turn their attention towards the Euro.

In 2006, a Pakistani government printing press in the city of Quetta was accused of churning out large quantities of counterfeit Indian currency, The Times of India reported based on Central Bureau of Intelligence investigation. The rupee notes are then smuggled into India as 'part of Pakistan's agenda of destabilising (the) Indian economy through fake currency,' the daily said. The notes are 'supplied by the Pakistan government press (at Quetta) free of cost to Dubai-based counterfeiters who, in turn, smuggle it into India using various means,' the report said.[4] This money is allegedly used to fund terrorist activities inside India. The recent blasts in Mumbai were allegedly funded using fake currency printed in Pakistan.

Effect on society

Some of the ill-effects that counterfeit money has on society are:[5][6]

- Reduction in the value of real money

- Increase in prices (inflation) due to more money getting circulated in the economy - an unauthorized artificial increase in the money supply

- Decrease in the acceptability (satisfactoriness) of money - payees may demand electronic transfers of real money or payment in another currency (or even payment in a precious metal such as gold)

- Companies are not reimbursed for counterfeits. This forces them to increase prices of commodities

At the same time, in countries where paper money is a small fraction of the total money in circulation, the macroeconomic effects of counterfeiting of currency may not be significant. The microeconomic effects, such as confidence in currency, however, may be large.[7]

Anti-counterfeiting measures

Traditionally, anti-counterfeiting measures involved including fine detail with raised intaglio printing on bills which would allow non-experts to easily spot forgeries. On coins, milled or reeded (marked with parallel grooves) edges are used to show that none of the valuable metal has been scraped off. This detects the shaving or clipping (paring off) of the rim of the coin. However, it does not detect sweating, or shaking coins in a bag and collecting the resulting dust. Since this technique removes a smaller amount, it is primarily used on the most valuable coins, such as gold. In early paper money in Colonial North America, one creative means of deterring counterfeiters was to print the impression of a leaf in the bill. Since the patterns found in a leaf were unique and complex, they were nearly impossible to reproduce.[2]

In the late twentieth century advances in computer and photocopy technology made it possible for people without sophisticated training to easily copy currency. In response, national engraving bureaus began to include new more sophisticated anti-counterfeiting systems such as holograms, multi-colored bills, embedded devices such as strips, microprinting and inks whose colors changed depending on the angle of the light, and the use of design features such as the "EURion constellation" which disables modern photocopiers. Software programs such as Adobe Photoshop have been modified by their manufacturers to obstruct manipulation of scanned images of banknotes.[8] There also exist patches to counteract these measures.

For U.S. currency, anti-counterfeiting milestones are as follows:

- 1996 $100 bill gets a new design with a larger portrait

- 1997 $50 bill gets a new design with a larger portrait

- 1998 $20 bill gets a new design with a larger portrait

- 2000 $10 bill and $5 bill get a new design with a larger portrait

- 2003 $20 bill gets a new design with no oval around Andrew Jackson's portrait and more colors

- 2004 $50 bill gets a new design with no oval around Ulysses S. Grant's portrait and more colors

- 2006 $10 bill gets a new design with no oval around Alexander Hamilton's portrait and more colors

- 2008 $5 bill gets a new design with no oval around Abraham Lincoln's portrait and more colors

The Treasury had made no plans to redesign the $5 bill using colors, but recently reversed its decision, after learning some counterfeiters were bleaching the ink off the bills and printing them as $100 bills. It is not known when the $100 bill will be redesigned in this format, but the new $10 bill (the design of which was revealed in late 2005) entered circulation on March 2, 2006. The $1 bill and $2 bill are seen by most counterfeiters as having too low of a value to counterfeit, and so they have not been redesigned as frequently as higher denominations.

In the 1980s counterfeiting in the Republic of Ireland twice resulted in sudden changes in official documents: in November 1984 the £1 postage stamp, also used on savings cards for paying television licences and telephone bills, was invalidated and replaced by another design at a few days' notice, because of widespread counterfeiting. Later, the £20 Central Bank of Ireland Series B banknote was rapidly replaced because of what the Finance Minister described as "the involuntary privatisation of banknote printing".

In the 1990s, the portrait of Chairman Mao Zedong was placed on the banknotes of the People's Republic of China to combat counterfeiting, as he was recognised better than the generic designs on the renminbi notes.

In 1988 The Reserve Bank of Australia, released the world's first long lasting and counterfeit resistant polymer (plastic) banknotes with a special Bicentennial $10 note issue, the problems discovered were addressed and in 1992 a problem free $5 note was issued. In 1996 Australia became the first country to have a full series of circulating polymer banknotes.[9] On 3 May 1999 the New Zealand Reserve Bank started circulating polymer banknotes printed by Note Printing Australia Limited. [10]. The technology developed is now used in 26 countries. [11] Note Printing Australia is currently printing polymer notes for 18 countries.[12]

The Swiss National Bank has a reserve series of notes for the Swiss Franc bill, in case widespread counterfeiting were to take place.

Money art

A subject related to that of counterfeiting is that of money art, which is art that incorporates currency designs or themes. Some of these works of art are similar enough to actual bills that their legality is in question. While a counterfeit is made with deceptive intent, money art is not - however, the law may or may not differentiate between the two. See JSG Boggs, the American artist best known for his hand-drawn, one-sided copies of US banknotes which he spends for the face value of the note.

Famous counterfeiters

Cartoon in Punch magazine 25 August 1920. A half crown was a coin worth one-eighth of a pound.

- Eric "Klipping" V - The King of Denmark (1259-1286). The king’s nickname refers to ”clipping” of the coin.

- Frank William Abagnale Jr., - Worked under 8 identities, including his first as Pan American Airlines Pilot Frank Williams, in over 5 years, passing over $2.5 million in bogus checks in over 26 countries and all 50 states. He was arrested in France at an Air France ticket counter when an agent recognized his face from a wanted poster, and then was extradited to Sweden and then back to the United States. The movie Catch Me if You Can was loosely based on his life.

- Anatasios Arnaouti - a British counterfeiter of more than £2.5 million in fake money, sentenced in 2005

- Abel Buell - American colonialist who went from altering five-pound note engraving plates to publishing the first map of the new United States created by an American.

- Mary Butterworth - a counterfeiter in colonial America

- William Chaloner, - A successful British counterfeiter convicted by Sir Isaac Newton and hanged, drawn and quartered on 23 March 1699.

- Alves dos Reis - By the end of 1925 Reis had managed to introduce escudo banknotes worth £1,007,963 at 1925 exchange rates into the Portuguese economy, which was equivalent to 0.88% of Portugal’s nominal GDP at the time.

- Stephen Jory - Great Britain's most renowned counterfeiter, he started his career by selling cheap perfume in designer bottles. He later established his own illegal printing operation to produce and distribute an estimated five billion pounds in counterfeit currency throughout the United Kingdom.

- Rick Masters (fictional character, played by Willem Dafoe) - a master counterfeiter in William Friedkin's movie To Live and Die in L.A..

- Catherine Murphy was convicted of coining in 1789 and was the last woman to suffer execution by burning in England.

- Samuel C. Upham - the first known counterfeiter of Confederate money during the American Civil War. His activities began or became known in early July 1862.

- E.M. Washington, produces artwork attributed to his fictitious grandfather and other 20th Century artists.

- Edward Mueller - Documented in Mister 880, he was possibly the longest uncaught counterfeiter in history[13]. For ten or more years he eluded government authorities while he printed and spent fake $1 bills in his New York neighborhood.[14]

- Wesley Weber - was sent to prison for counterfeiting the Canadian 100 dollar bill.

Counterfeiting of documents

Forgery is the process of making or adapting documents with the intention to deceive. It is a form of fraud, and is often a key technique in the execution of identity theft. Uttering and publishing is a term in United States law for the forgery of non-official documents, such as a trucking company's time and weight logs.

Questioned document examination is a scientific process for investigating many aspects of various documents, and is often used to examine the provenance and verity of a suspected forgery. Security printing is a printing industry specialty, focused on creating documents which are difficult or impossible to forge.

Counterfeiting of consumer goods

The spread of counterfeit goods has become global in recent years and the range of goods subject to infringement has increased significantly. According to the study of Counterfeiting Intelligence Bureau (CIB) of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) counterfeit Goods make up 5 to 7% of World Trade, however, these figures cannot be substantiated.[15]. According to the International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition if the knockoff economy were a business, it would be the world’s biggest. [16] A recent report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development indicates that up to 200 Billion U.S. Dollars of international trade could have been in counterfeit and pirated goods in 2005 (2% of World Trade in 2005) [17]

Certain consumer goods, especially very expensive or desirable brands, or those which are easy to reproduce cheaply, have become frequent targets of counterfeiting. The counterfeiters attempt to deceive the consumer into thinking they are purchasing a legitimate item, or convince the consumer that they could deceive others with the imitation. An item which doesn't attempt to deceive, such as a copy of a DVD with missing or different cover art, is often called a "bootleg" or a "pirated copy" instead.

Some counterfeits may even have been produced in the same factory that produces the original, authentic product, using the same materials. The factory owner, unbeknownst to the trademark owner (and perhaps also the manufacturing staff), simply orders an intentional 'overrun'. Without the employment of anti-counterfeiting measures, identical manufacturing methods and materials make this type of counterfeit (and it is still a form of counterfeit, as its production and sale is unauthorized by the trademark owner) impossible to distinguish from the authentic article.

To try to avoid this all too common occurrence, companies may have the various parts of an item manufactured in independent factories and then limit the supply of certain distinguishing parts to the factory that performs the final assembly to the exact number required for the number of items to be assembled (or as near to that number as is practicable) and/or may require the factory to account for every part used and to return any unused, faulty, or damaged parts. To help distinguish the originals from the counterfeits, the copyright holder may also employ the use of serial numbers and/or holograms etc., which may be attached to the product in another factory still.

Apparel and accessories

Counterfeit clothes, shoes and handbags from designer brands such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Gucci and Lacoste are made in varying quality; sometimes the intent is only to fool the gullible buyer who only looks at the label and doesn't know what the real thing looks like, while others put some serious effort into mimicking fashion details. The popularity of designer jeans, starting with Jordache in 1978, spurred a flood of knockoffs. Factories that manufacture counterfeit designer brand garments and watches are usually located in developing countries such as China and Thailand. Many international tourists visiting Beijing will find a wide selection of counterfeit designer brand garments at the infamous Silk Street. In Bangkok, the majority of goods for sale on the street and in markets such as Chatuchak market, the world's largest counterfeit market.

Expensive watches such as Rolex and Patek Philippe are vulnerable to counterfeiting; it is a common cliché that any visitor to New York City will be approached on a street corner by a vendor with a dozen such counterfeit watches inside his coat, offered at amazing bargain prices. It has been known that some of the watches have no real hands at all, but merely painted faces, and in some cases, not even a movement. While the buyer walks off, the vendor makes a hasty getaway.

In Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines, extremely authentic looking, but very poor quality watch fakes with self-winding mechanisms and fully working movements can sell for as little as US $20. On the other hand, some fakes' movements and materials are of remarkably passable quality — albeit inconsistently so — and may look good and work well for some years, a possible consequence of increasing competition within the counterfeiting community.

Media products

Compact Discs, videotapes and DVDs, computer software and other media which are easily copied can be counterfeited, and sold through vendors at street markets, night markets, mail order, and numerous Internet sources, including open auction sites like eBay.

Music enthusiasts may use the term "bootleg recording" to differentiate otherwise unavailable recordings from counterfeited copies of commercially released material.

In India, copies of bestselling books with photocopied jackets sell for a fraction of the genuine retail price. They are openly sold on streetcorners, with hundreds of copies spread out on blankets.

Drugs

A counterfeit drug or medicine is one which is produced and sold with the intent to deceptively represent its origin, authenticity or effectiveness. It may be one which does not contain active ingredients, contains an insufficient or inaccurate quantity of active ingredients, or contains entirely incorrect active ingredients (which may or may not be harmful), and may be sold with inaccurate, incorrect, or fake packaging. There is also a significant trade in high quality counterfeit pharmaceutical drugs.

Illegal recreational drugs may also be counterfeited, either for profit or for the deception of rival drug distributors or narcotics officers.

Generic drugs that are legally manufactured and sold without deceptive representations regarding origin, authenticity or effectiveness are not counterfeits. Fake Viagra is common in many parts of the world.

Food

Counterfeit foods include artificial soy sauce and falsely high protein milk products, as well as many manufacturers of food which copy trademarks of other well known manufacturers, prevalent in much of China and Southeast Asia.

Companies

Third World nations, especially in Southeast Asia and China, have en masse copied corporate logos and names of primarily Western and Japanese companies. Some of these companies have even become listed on stock exchanges in their respective nations, such as Pensonic, a Panasonic knockoff in Malaysia. Other companies continue to operate in their respective industries, such as Hanabishi, a knockoff of Mitsubishi Electric, whom it shares a similar 3-branched red logo. Ironically, its the "Mitsu" part that means three, not the "bishi". Others have taken famous trade names and used them for industries other than which they knocked off, such as Hatari, which is a Thai manufacturer of electric fans based on the Atari name, and TOA Paint, which is based on Japan's TOA Corp. name, but doesn't manufacture electronics at all. Other companies simply created a Japanese sounding name and logo, which is not technically copyright infringement, without actually having any association with Japan, as in Saijo Denki of Thailand. Other lesser known companies in Malaysia are Fujisu (of Fujitsu), MEC (Malaysia Electronics Company) of NEC as well as Bampers (of Pampers). Kawamichi Snd Bhd (knockoff of Nakamichi) of Malaysia has had its website shut down.

See also

|

|

|

References

- ↑ 中国科普博览_印刷博物馆

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.librarycompany.org/BFWriter/images/large/3.7.jpg

- ↑ Malkin,Lawrence "Krueger's Men: The Secret Nazi Counterfeit Plot and the Prisoners of Block 19" (2006) ISBN 0-316-05700-2 ISBN 978-0-316005700-4

- ↑ Pakistan printing fake Indian currency - Times of India at Forbes

- ↑ "Counterfeiting of American Currency" pp 13. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ "Counterfeit Money, Who Takes the Hit?". William F Hummel. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ "Counterfeit Banknotes" (PDF). Parliamentary office of Science and Tech., UK. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Photoshop and CDS

- ↑ Powerhouse museum

- ↑ New Zealand Reserve Bank

- ↑ Securency

- ↑ Note Printing Australia

- ↑ http://www.dinepride.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=19993&sid=2f90dc0177a7a3de2f903bc9a843ddfc

- ↑ http://www.americanvision.org/osafarchive/april2005.asp

- ↑ ICC Counterfeiting Intelligence Bureau (1997), Countering Counterfeiting: A Guide to Protecting and Enforcing Intellectual Property Rights, United Kingdom.

- ↑ Welcome to KITSCHPURSES.COM

- ↑ "The Economic Effect of Counterfeiting and Piracy, Executive Summary" (PDF). OECD, Paris (2007). Retrieved on 2007.

- Detecting the Truth: Fakes, Forgeries and Trickery, a virtual museum exhibition at Library and Archives Canada