Correlation

In probability theory and statistics, correlation (often measured as a correlation coefficient) indicates the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two random variables. That is in contrast with the usage of the term in colloquial speech, denoting any relationship, not necessarily linear. In general statistical usage, correlation or co-relation refers to the departure of two random variables from independence. In this broad sense there are several coefficients, measuring the degree of correlation, adapted to the nature of the data.

A number of different coefficients are used for different situations. The best known is the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, which is obtained by dividing the covariance of the two variables by the product of their standard deviations. Despite its name, it was first introduced by Francis Galton.[1]

Pearson's product-moment coefficient

Mathematical properties

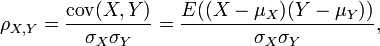

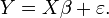

The correlation coefficient ρX, Y between two random variables X and Y with expected values μX and μY and standard deviations σX and σY is defined as:

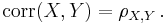

where E is the expected value operator and cov means covariance. A widely used alternative notation is

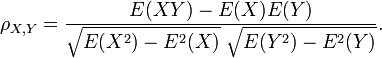

Since μX = E(X), σX2 = E[(X - E(X))2] = E(X2) − E2(X) and likewise for Y, we may also write

The correlation is defined only if both of the standard deviations are finite and both of them are nonzero. It is a corollary of the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality that the correlation cannot exceed 1 in absolute value.

The correlation is 1 in the case of an increasing linear relationship, −1 in the case of a decreasing linear relationship, and some value in between in all other cases, indicating the degree of linear dependence between the variables. The closer the coefficient is to either −1 or 1, the stronger the correlation between the variables.

If the variables are independent then the correlation is 0, but the converse is not true because the correlation coefficient detects only linear dependencies between two variables. Here is an example: Suppose the random variable X is uniformly distributed on the interval from −1 to 1, and Y = X2. Then Y is completely determined by X, so that X and Y are dependent, but their correlation is zero; they are uncorrelated. However, in the special case when X and Y are jointly normal, uncorrelatedness is equivalent to independence.

A correlation between two variables is diluted in the presence of measurement error around estimates of one or both variables, in which case disattenuation provides a more accurate coefficient.

The sample correlation

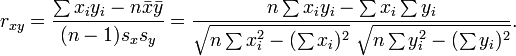

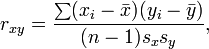

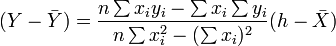

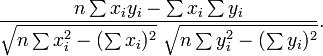

If we have a series of n measurements of X and Y written as xi and yi where i = 1, 2, ..., n, then the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient can be used to estimate the correlation of X and Y . The Pearson coefficient is also known as the "sample correlation coefficient". The Pearson correlation coefficient is then the best estimate of the correlation of X and Y . The Pearson correlation coefficient is written:

where  and

and  are the sample means of X and Y , sx and sy are the sample standard deviations of X and Y and the sum is from i = 1 to n. As with the population correlation, we may rewrite this as

are the sample means of X and Y , sx and sy are the sample standard deviations of X and Y and the sum is from i = 1 to n. As with the population correlation, we may rewrite this as

Again, as is true with the population correlation, the absolute value of the sample correlation must be less than or equal to 1. Though the above formula conveniently suggests a single-pass algorithm for calculating sample correlations, it is notorious for its numerical instability (see below for something more accurate).

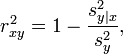

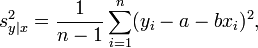

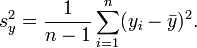

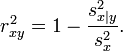

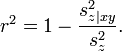

The square of the sample correlation coefficient, which is also known as the coefficient of determination, is the fraction of the variance in yi that is accounted for by a linear fit of xi to yi . This is written

where sy|x2 is the square of the error of a linear regression of xi on yi by the equation y = a + bx:

and sy2 is just the variance of y:

Note that since the sample correlation coefficient is symmetric in xi and yi , we will get the same value for a fit of yi to xi :

This equation also gives an intuitive idea of the correlation coefficient for higher dimensions. Just as the above described sample correlation coefficient is the fraction of variance accounted for by the fit of a 1-dimensional linear submanifold to a set of 2-dimensional vectors (xi , yi ), so we can define a correlation coefficient for a fit of an m-dimensional linear submanifold to a set of n-dimensional vectors. For example, if we fit a plane z = a + bx + cy to a set of data (xi , yi , zi ) then the correlation coefficient of z to x and y is

The distribution of the correlation coefficient has been examined by R. A. Fisher[2][3] and A. K. Gayen.[4]

Geometric Interpretation of correlation

For centered data (i.e., data which have been shifted by the sample mean so as to have an average of zero), the correlation coefficient can also be viewed as the cosine of the angle between the two vectors of samples drawn from the two random variables.

Some practitioners prefer an uncentered (non-Pearson-compliant) correlation coefficient. See the example below for a comparison.

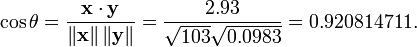

As an example, suppose five countries are found to have gross national products of 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8 billion dollars, respectively. Suppose these same five countries (in the same order) are found to have 11%, 12%, 13%, 15%, and 18% poverty. Then let x and y be ordered 5-element vectors containing the above data: x = (1, 2, 3, 5, 8) and y = (0.11, 0.12, 0.13, 0.15, 0.18).

By the usual procedure for finding the angle between two vectors (see dot product), the uncentered correlation coefficient is:

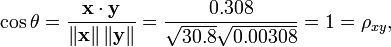

Note that the above data were deliberately chosen to be perfectly correlated: y = 0.10 + 0.01 x. The Pearson correlation coefficient must therefore be exactly one. Centering the data (shifting x by E(x) = 3.8 and y by E(y) = 0.138) yields x = (−2.8, −1.8, −0.8, 1.2, 4.2) and y = (−0.028, −0.018, −0.008, 0.012, 0.042), from which

as expected.

Motivation for the form of the coefficient of correlation

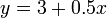

Another motivation for correlation comes from inspecting the method of simple linear regression. As above, X is the vector of independent variables,  , and Y of the dependent variables,

, and Y of the dependent variables,  , and a simple linear relationship between X and Y is sought, through a least-squares method on the estimate of Y:

, and a simple linear relationship between X and Y is sought, through a least-squares method on the estimate of Y:

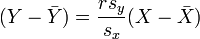

Then, the equation of the least-squares line can be derived to be of the form:

which can be rearranged in the form:

where r has the familiar form mentioned above :

Interpretation of the size of a correlation

| Correlation | Negative | Positive |

|---|---|---|

| Small | −0.3 to −0.1 | 0.1 to 0.3 |

| Medium | −0.5 to −0.3 | 0.3 to 0.5 |

| Large | −1.0 to −0.5 | 0.5 to 1.0 |

Several authors have offered guidelines for the interpretation of a correlation coefficient. Cohen (1988),[5] has observed, however, that all such criteria are in some ways arbitrary and should not be observed too strictly. This is because the interpretation of a correlation coefficient depends on the context and purposes. A correlation of 0.9 may be very low if one is verifying a physical law using high-quality instruments, but may be regarded as very high in the social sciences where there may be a greater contribution from complicating factors.

Along this vein, it is important to remember that "large" and "small" should not be taken as synonyms for "good" and "bad" in terms of determining that a correlation is of a certain size. For example, a correlation of 1.0 or −1.0 indicates that the two variables analyzed are equivalent modulo scaling. Scientifically, this more frequently indicates a trivial result than a profound one. For example, consider discovering a correlation of 1.0 between how many feet tall a group of people are and the number of inches from the bottom of their feet to the top of their heads.

Non-parametric correlation coefficients

Pearson's correlation coefficient is a parametric statistic and when distributions are not normal it may be less useful than non-parametric correlation methods, such as Chi-square, Point biserial correlation, Spearman's ρ, Kendall's τ, and Goodman and Kruskal's lambda. They are a little less powerful than parametric methods if the assumptions underlying the latter are met, but are less likely to give distorted results when the assumptions fail.

Other measures of dependence among random variables

The information given by a correlation coefficient is not enough to define the dependence structure between random variables. The correlation coefficient completely defines the dependence structure only in very particular cases, for example when the cumulative distribution functions are the multivariate normal distributions. (See diagram above.) In the case of elliptic distributions it characterizes the (hyper-)ellipses of equal density, however, it does not completely characterize the dependence structure (for example, the a multivariate t-distribution's degrees of freedom determine the level of tail dependence).

To get a measure for more general dependencies in the data (also nonlinear) it is better to use the correlation ratio which is able to detect almost any functional dependency, or the entropy-based mutual information/total correlation which is capable of detecting even more general dependencies. The latter are sometimes referred to as multi-moment correlation measures, in comparison to those that consider only 2nd moment (pairwise or quadratic) dependence.

The polychoric correlation is another correlation applied to ordinal data that aims to estimate the correlation between theorised latent variables.

One way to capture a more complete view of dependence structure is to consider a copula between them.

Correlation matrices

The correlation matrix of n random variables X1, ..., Xn is the n × n matrix whose i,j entry is corr(Xi, Xj). If the measures of correlation used are product-moment coefficients, the correlation matrix is the same as the covariance matrix of the standardized random variables Xi /SD(Xi) for i = 1, ..., n. Consequently it is necessarily a positive-semidefinite matrix.

The correlation matrix is symmetric because the correlation between  and

and  is the same as the correlation between

is the same as the correlation between  and

and  .

.

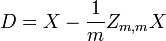

Removing correlation

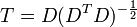

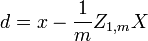

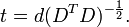

It is always possible to remove the correlation between zero-mean random variables with a linear transform, even if the relationship between the variables is nonlinear. Suppose a vector of n random variables is sampled m times. Let X be a matrix where  is the jth variable of sample i. Let

is the jth variable of sample i. Let  be an r by c matrix with every element 1. Then D is the data transformed so every random variable has zero mean, and T is the data transformed so all variables have zero mean, unit variance, and zero correlation with all other variables. The transformed variables will be uncorrelated, even though they may not be independent.

be an r by c matrix with every element 1. Then D is the data transformed so every random variable has zero mean, and T is the data transformed so all variables have zero mean, unit variance, and zero correlation with all other variables. The transformed variables will be uncorrelated, even though they may not be independent.

where an exponent of -1/2 represents the matrix square root of the inverse of a matrix. The covariance matrix of T will be the identity matrix. If a new data sample x is a row vector of n elements, then the same transform can be applied to x to get the transformed vectors d and t:

Common misconceptions about correlation

Correlation and causality

The conventional dictum that "correlation does not imply causation" means that correlation cannot be validly used to infer a causal relationship between the variables. This dictum should not be taken to mean that correlations cannot indicate causal relations. However, the causes underlying the correlation, if any, may be indirect and unknown. Consequently, establishing a correlation between two variables is not a sufficient condition to establish a causal relationship (in either direction).

A correlation between age and height in children is fairly causally transparent, but a correlation between mood and health in people is less so. Does improved mood lead to improved health; or does good health lead to good mood; or both? Or does some other factor underlie both? Or is it pure coincidence? In other words, a correlation can be taken as evidence for a possible causal relationship, but cannot indicate what the causal relationship, if any, might be.

Correlation and linearity

While Pearson correlation indicates the strength of a linear relationship between two variables, its value alone may not be sufficient to evaluate this relationship, especially in the case where the assumption of normality is incorrect.

The image on the right shows scatterplots of Anscombe's quartet, a set of four different pairs of variables created by Francis Anscombe.[6] The four  variables have the same mean (7.5), standard deviation (4.12), correlation (0.81) and regression line (

variables have the same mean (7.5), standard deviation (4.12), correlation (0.81) and regression line ( ). However, as can be seen on the plots, the distribution of the variables is very different. The first one (top left) seems to be distributed normally, and corresponds to what one would expect when considering two variables correlated and following the assumption of normality. The second one (top right) is not distributed normally; while an obvious relationship between the two variables can be observed, it is not linear, and the Pearson correlation coefficient is not relevant. In the third case (bottom left), the linear relationship is perfect, except for one outlier which exerts enough influence to lower the correlation coefficient from 1 to 0.81. Finally, the fourth example (bottom right) shows another example when one outlier is enough to produce a high correlation coefficient, even though the relationship between the two variables is not linear.

). However, as can be seen on the plots, the distribution of the variables is very different. The first one (top left) seems to be distributed normally, and corresponds to what one would expect when considering two variables correlated and following the assumption of normality. The second one (top right) is not distributed normally; while an obvious relationship between the two variables can be observed, it is not linear, and the Pearson correlation coefficient is not relevant. In the third case (bottom left), the linear relationship is perfect, except for one outlier which exerts enough influence to lower the correlation coefficient from 1 to 0.81. Finally, the fourth example (bottom right) shows another example when one outlier is enough to produce a high correlation coefficient, even though the relationship between the two variables is not linear.

These examples indicate that the correlation coefficient, as a summary statistic, cannot replace the individual examination of the data.

Computing correlation accurately in a single pass

The following algorithm (in pseudocode) will calculate Pearson correlation with good numerical stability.

sum_sq_x = 0 sum_sq_y = 0 sum_coproduct = 0 mean_x = x[1] mean_y = y[1] for i in 2 to N: sweep = (i - 1.0) / i delta_x = x[i] - mean_x delta_y = y[i] - mean_y sum_sq_x += delta_x * delta_x * sweep sum_sq_y += delta_y * delta_y * sweep sum_coproduct += delta_x * delta_y * sweep mean_x += delta_x / i mean_y += delta_y / i pop_sd_x = sqrt( sum_sq_x / N ) pop_sd_y = sqrt( sum_sq_y / N ) cov_x_y = sum_coproduct / N correlation = cov_x_y / (pop_sd_x * pop_sd_y)

This is a working example in Ada language:

with Ada.Text_IO; use Ada.Text_IO; with Ada.Numerics.Generic_Elementary_Functions; procedure pearson_correlation is package Maths is new Ada.Numerics.Generic_Elementary_Functions (Float); use Maths; N : Integer := 7; x : array ( 1 .. N ) of Float := ( 1.2, 3.7, 0.1, 3.0, 3.0, 2.9, 2.2 ); y : array ( 1 .. N ) of Float := ( 2.0, 7.1, 0.5, 6.1, 6.1, 6.1, 4.4 ); sum_sq_x, sum_sq_y, sum_coproduct, mean_x, mean_y, sweep : Float; delta_x, delta_y, pop_sd_x, pop_sd_y, cov_x_y, correlation : Float; begin sum_sq_x := 0.0; sum_sq_y := 0.0; sum_coproduct := 0.0; mean_x := x(1); mean_y := y(1); for i in 2 .. N loop sweep := (Float(i) - 1.0) / Float(i); delta_x := x(i) - mean_x; delta_y := y(i) - mean_y; sum_sq_x := sum_sq_x + delta_x * delta_x * sweep; sum_sq_y := sum_sq_y + delta_y * delta_y * sweep; sum_coproduct := sum_coproduct + delta_x * delta_y * sweep; mean_x := mean_x + delta_x / Float(i); mean_y := mean_y + delta_y / Float(i); end loop; pop_sd_x := Sqrt( sum_sq_x / Float(N) ); pop_sd_y := Sqrt( sum_sq_y / Float(N) ); cov_x_y := sum_coproduct / Float(N); correlation := cov_x_y / (pop_sd_x * pop_sd_y); Put_Line ("Result: " & Float'Image (correlation)); end pearson_correlation;

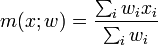

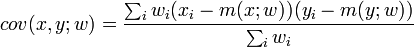

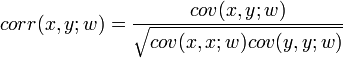

Calculating a weighted correlation

Suppose observations to be correlated have differing degrees of importance that can be expressed with a weight vector  . To calculate the correlation between vectors

. To calculate the correlation between vectors  and

and  with the weight vector

with the weight vector  (all of length

(all of length  ), [7][8]

), [7][8]

- Weighted Mean:

- Weighted Covariance

- Weighted Correlation

See also

- Autocorrelation

- Association (statistics)

- Cross-correlation

- Coefficient of determination

- Fraction of variance unexplained

- Goodman and Kruskal's lambda

- Kendall's tau

- Linear correlation (wikiversity)

- Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient

- Point-biserial correlation coefficient

- Partial correlation

- Spearman's rank correlation coefficient

- Statistical arbitrage

- Currency correlation

Notes and references

- ↑ Rodgers, J. L. and Nicewander, W. A. (1988). "Thirteen ways to look at the correlation coefficient". The American Statistician 42: 59–66. doi:.

- ↑ R. A. Fisher (1915). "Frequency distribution of the values of the correlation coefficient in samples from an indefinitely large population". Biometrika 10: 507–521.

- ↑ R. A. Fisher (1921). "On the probable error of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample". Metron.

- ↑ A. K. Gayen (1951). "The frequency distribution of the product moment correlation coefficient in random samples of any size draw from non-normal universes". Biometrika 38: 219–247.

- ↑ Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.)

- ↑ Anscombe, Francis J. (1973) Graphs in statistical analysis. American Statistician, 27, 17–21.

- ↑ http://sci.tech-archive.net/Archive/sci.stat.math/2006-02/msg00171.html

- ↑ A MATLAB Toolbox for computing Weighted Correlation Coefficients

Further reading

- Cohen, J., Cohen P., West, S.G., & Aiken, L.S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. (3rd ed.) Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

External links

- Understanding Correlation - Introductory material by a U. of Hawaii Prof.

- Online Utility to Compute Correlation Coefficient (Scatter Diagram)

- Statsoft Electronic Textbook

- Pearson's Correlation Coefficient - How to calculate it quickly

- Learning by Simulations - The distribution of the correlation coefficient

- Correlation measures the strength of a linear relationship between two variables.

- MathWorld page on (cross-) correlation coefficient(s) of a sample.

- Compute Significance between two correlations - A useful website if one wants to compare two correlation values.

- A MATLAB Toolbox for computing Weighted Correlation Coefficients

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||