Coriolanus (play)

Coriolanus is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, based on the life of the legendary Roman leader, Gaius Martius Coriolanus.

Contents |

Source

Coriolanus was largely based on the Life of Coriolanus as it was described in Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans and Livy's Ab Urbe condita.

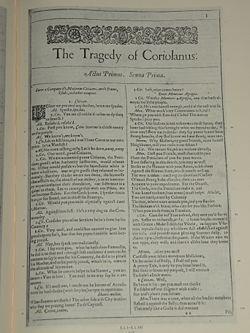

Date and text

It was originally published in the First Folio of 1623. Elements of the text, such as the uncommonly detailed stage directions, lead some Shakespeare scholars to believe the text was prepared from a theatrical prompt book.

Characters

- Caius Martius, later surnamed Coriolanus

- Menenius Agrippa, Senator of Rome

- Cominius, Titus Lartius, generals

- Volumnia, Coriolanus's mother

- Virgilia, Coriolanus's wife

- Young Martius, Coriolanus's son

- Valeria, a lady of Rome

- Sicinius Velutus, Junius Brutus, tribunes of Rome

- Citizens of Rome

- Soldiers in the Roman Army

- Tullus Aufidius, general of the Volscian army

- Aufidius's Lieutenant

- Aufidius's Servingmen

- Conspirators with Aufidius

- Volscian Lords

- Volscian Citizens

- Soldiers in the Volscian army

- Adrian, a Volscian

- Nicanor, a Roman

- A Roman Herald

- Messengers

- Aediles

- A gentlewoman, an usher, Roman and Volscian senators and nobles, captains in the Roman army, officers, lictors

Synopsis

The play opens in Rome, shortly after the expulsion of the Tarquin kings. There are riots in progress, after stores of grain were withheld from ordinary citizens. The rioters are particularly angry at Caius Martius, a brilliant Roman general whom they blame for the grain being taken away. The rioters encounter a patrician named Menenius Agrippa, as well as Caius Martius himself. Menenius tries to calm the rioters, while Martius is openly contemptuous, and says that the plebeians were not worthy of the grain because of their lack of military service. Two of the tribunes of Rome, Brutus and Sicinius, privately denounce Martius. He leaves Rome after news arrives that a Volscian army is in the field.

The commander of the Volscian army, Tullus Aufidius, has fought with Martius on several occasions, and considers him a blood enemy. The Roman army is commanded by Cominius, with Martius as his deputy. While Cominius takes his soldiers to meet Aufidius' army, Martius leads a sally against the Volscian city of Corioles. The siege of Corioles is initially unsuccessful, but Martius is able to force open the gates of the city, and the Romans conquer it. Even though he is exhausted from the fighting, Martius marches quickly to join Cominius and fight the other Volscian force. Martius and Aufidius meet in single combat, which only ends when Aufidius' own soldiers drag him away from the battle.

In recognition of his incredible bravery, Cominius gives Martius the honorific surname of "Coriolanus". When they return to Rome, Coriolanus' mother Volumnia encourages her son to run for consul. Coriolanus is hesitant to do this, but he bows to his mother's wishes. He effortlessly wins the support of the Roman Senate, and seems at first to have won over the commoners as well. However, Brutus and Sicinius scheme to undo Coriolanus, and whip up another riot in opposition to him becoming consul. Faced with this opposition, Coriolanus flies into a rage, and rails against the concept of popular rule. He compares allowing plebeians to have power over the patricians to allowing "crows to peck the eagles". The two tribunes condemn Coriolanus as a traitor for his words, and order him to be banished.

After being exiled from Rome, Coriolanus seeks out Aufidius in the Volscian capital, and tells them that he will lead their army to victory against Rome. Aufidius and his superiors embrace Coriolanus, and allow him to lead a new assault on the city.

Rome, in its panic, tries desperately to persuade Coriolanus to halt his crusade for vengeance, but both Cominius and Menenius fail. Finally, Volumnia is sent to meet with her son, along with Coriolanus' wife and child, and another lady. Volumnia succeeds in dissuading her son from destroying Rome, and Coriolanus instead concludes a peace treaty between the Volscians and the Romans. When Coriolanus returns to the Volscian capital, conspirators, organised by Aufidius, kill him for his betrayal.

Performance history

Like some of Shakespeare's other plays (All's Well That Ends Well; Timon of Athens), there is no recorded performance of Coriolanus prior to the Restoration. After 1660, however, its themes made it a natural choice for times of political turmoil. The first known performance was Nahum Tate's bloody 1682 adaptation at Drury Lane. Seemingly undeterred by the earlier suppression of his Richard II, Tate offered a Coriolanus that was faithful to Shakespeare through four acts before becoming a Websterian bloodbath in the fifth act. A later adaptation, John Dennis's The Invader of His Country, or The Fatal Resentment, was booed off the stage after three performances in 1719. The title and date indicate Dennis's intent, a vitriolic attack on the Jacobite 'Fifteen. (Similar intentions motivated James Thomson's 1745 version, though this bears only a very slight resemblance to Shakespeare's play. Its principal connection to Shakespeare is indirect; Thomas Sheridan's 1752 production at Smock Alley used some passages of Thomson's. David Garrick returned to Shakespeare's text in a 1754 Drury Lane production.[1]

The most famous Coriolanus in history is Laurence Olivier, who first played the part triumphantly at the Old Vic Theatre in 1937 and returned to it to even greater acclaim at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in 1959. In that production, he famously performed Coriolanus's death scene by dropping backwards from a high platform and being suspended upside-down (without the aid of wires), being reminiscent of Mussolini.[2]

Another notable Coriolanus of the twentieth century was Richard Burton, who also recorded the complete play for Caedmon Records.

Other famous performances of Coriolanus include Ian McKellen, Toby Stephens, Gerard Butler, and Ralph Fiennes. Alan Howard played Coriolanus in the 1984 BBC production.

Critical appraisal

A. C. Bradley described this play as "built on the grand scale,"[3] like King Lear and Macbeth, but it differs from those two masterpieces in an important way. The warrior Coriolanus is perhaps the most opaque of Shakespeare's tragic heroes, rarely pausing to soliloquize or reveal the motives behind his prideful isolation from Roman society. In this way, he is less like effervescent, reflective Shakespearean heroes/heroines such as Macbeth, Hamlet, Lear and Cleopatra and more like figures from ancient classical literature such as Achilles, Odysseus, and Aeneas -- or, to turn to literary creations from Shakespeare's time, the Marlovian conqueror Tamburlaine, whose militaristic pride finds a descendant in Coriolanus. Readers and playgoers have often found him an unsympathetic character, although his caustic pride is strangely, almost delicately balanced at times by a reluctance to be praised by his compatriots and an unwillingness to exploit and slander for political gain. The play is less frequently produced than the other tragedies of the later period, and is not so universally regarded as "great." (Bradley, for instance, declined to number it among his famous four in the landmark critical work Shakespearean Tragedy.) In his book Shakespeare's Language, Frank Kermode described Coriolanus as "probably the most fiercely and ingeniously planned and expressed of all the tragedies".[4]

The political overtones in Coriolanus are rich and nuanced. The drama especially and thoroughly examines the divide between plebeian democracy (favored in the play by the tribunes Brutus and Sicinius) and the proponents of autocracy (represented by the Coriolanus and the consulship itself). The conspiring tribunes point out Coriolanus' flaws and anti-democratic sentiments to the plebians, which admittedly he does possess, but they do so as a trick of demagoguery so they can consolidate their own power, not out of a sense of the greater good. This makes the tribunes comparable to Cassius in Julius Caesar, who publicly justifies the murder of Caesar because Caesar wanted to be king, when in private Cassius was simply jealous of Caesar's power (as opposed to Brutus, who had the best interests of the republic in mind). Still, it is not a simple transposition of characters between Caesar and Coriolanus: Caesar himself is actually more of a demagogue than Cassius and the other senators, winning over the support of "the mob" of Rome by showering them with treasure from his conquests. However, there is an underlying subtext that Caesar is being manipulative of the plebeians and does want power, though with the nuance that it is ultimately what the republic needs. Coriolanus, in contrast, is openly anti-democratic yet a highly skilled soldier and commander, and not particularly ambitious. Indeed, Coriolanus is portrayed as actually quite deficient in political tact and doesn't rely on such "trickery": when he is initially winning the election (before the tribunes start another riot) he actually doesn't do particularly well, due to his poor rhetorical skills, but he does do well enough to win, because enough voters recognize that he is well qualified for the position.

As in Hamlet, an important relationship of the play is between a mother and her son, but in Coriolanus, this relationship is both less fractured and devoid of the sexual tension that exists between Gertrude and the Danish prince. Indeed, the most intriguing tension resides, not in the hero's relationship with any woman, but in that which he maintains with his nemesis (and eventual ally) Aufidius. Marital and romantic concerns, so prominent in Antony and Cleopatra, are almost wholly absent. The play maintains a serious tone throughout, without any of the familiar comic scenes, fools, or other stock devices commonly used by Shakespeare to lighten his tragedies. What comedy there is in the play may reside in Shakespeare's tart portrayal of the hypocrisy, cowardice, and fickleness of the plebeians.

T. S. Eliot famously proclaimed Coriolanus' superior to Hamlet in The Sacred Wood, in which he calls the former play, along with Antony and Cleopatra, the Bard's greatest tragic achievement. Eliot alludes to Coriolanus in a passage from his own The Waste Land.

Bertolt Brecht also adapted Shakespeare's play in 1952–5, as Coriolan for the Berliner Ensemble. He intended to make it a tragedy of the workers, not the individual, and introduce the alienation effect; his journal notes showing that he found many of his own effects already in the text, he considered staging the play with only minimal changes. The adaptation was unfinished at Brecht's death in 1956; it was completed by Manfred Wekwerth and Joachim Tenschert and staged in Frankfurt in 1962.[5]

Coriolanus has the distinction of being among the few Shakespeare plays banned in a democracy in modern times.[6] It was briefly suppressed in France in the late 1930s because of its use by the fascist element.[7]

References

- ↑ F. E. Halliday, A Shakespeare Companion 1564-1964, Baltimore, Penguin, 1964; p. 116.

- ↑ http://www.rsc.org.uk/searcharchives/search/data?type_id=1&field,RESOURCE_IDENTIFIER,substring,string=C_M982_34 Accessed 13 October 2008.

- ↑ Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy

- ↑ Kermode, Shakespeare's Language (Penguin Books 2001, p254).

- ↑ Brown, Langdon, ed. Shakespeare Around the Globe: A Guide to Notable Postwar Revivals (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986): 82.

- ↑ Maurois, Andre. The Miracle of France. Henri Lorin Binsse, trans. New York: Harpers, 1948: 432

- ↑ Parker 123

External links

- Text of the play by Shakespeare:

- Coriolanus complete text and translations. PDF

- http://www-tech.mit.edu/Shakespeare/coriolanus/ — Full text of Shakespeare's play

- The Tragedie of Coriolanus — HTML version of this title.

- Coriolanus by William Shakespeare — plain vanilla text from Project Gutenberg.

- Coriolanus - Scene-indexed and searchable version of the play.

- Plutarch's Life of Coriolanus :

- Plutarch's Life of Coriolanus — 17th century English translation by John Dryden

- Plutarch's Life of Coriolanus — 19th century English translation by Aubrey Stewart and George Long

Further reading

- Clark Lunberry In the Name of Coriolanus: The Prompter (Prompted). Comparative Literature 54: 3 (Summer 2002): 229-241.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||