Colorectal cancer

| Colorectal cancer Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

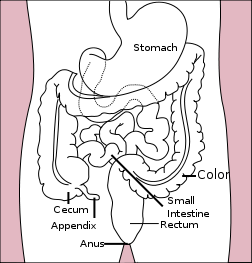

| Diagram of the stomach, colon, and rectum | |

| ICD-10 | C18.-C20. |

| ICD-9 | 153.0-154.1 |

| ICD-O: | M8140/3 (95% of cases) |

| OMIM | 114500 |

| DiseasesDB | 2975 |

| MedlinePlus | 000262 |

| eMedicine | med/413 med/1994 ped/3037 |

Colorectal cancer, also called colon cancer or large bowel cancer, includes cancerous growths in the colon, rectum and appendix. With 655,000 deaths worldwide per year, it is the third most common form of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the Western world.[1] Many colorectal cancers are thought to arise from adenomatous polyps in the colon. These mushroom-like growths are usually benign, but some may develop into cancer over time. The majority of the time, the diagnosis of localized colon cancer is through colonoscopy. Therapy is usually through surgery, which in many cases is followed by chemotherapy.

Contents |

Symptoms

The first symptoms of colon cancer are usually vague, like bleeding, weight loss, and fatigue (tiredness). Local (bowel) symptoms are rare until the tumor has grown to a large size. Generally, the nearer the tumor is to the anus, the more bowel symptoms there will be.

Symptoms and signs are divided into local, constitutional and metastatic.

Local symptoms

- Change in bowel habits

- Change in frequency (constipation and/or diarrhea),

- Feeling of incomplete defecation (tenesmus) and reduction in diameter of stool, both characteristic of rectal cancer,

- Change in the appearance of stools :

- Bloody stools or rectal bleeding

- Stools with mucus

- Black, tar-like stool (melena), more likely related to upper gastrointestinal eg stomach or duodenal disease

- Bowel obstruction causing bowel pain, bloating and vomiting of stool-like material.

- A tumor in the abdomen, felt by patients or their doctors.

- Symptoms related to invasion by the cancer of the bladder causing hematuria (blood in the urine) or pneumaturia (air in the urine), or invasion of the vagina causing smelly vaginal discharge. These are late events, indicative of a large tumor.

Constitutional (systemic) symptoms

- Unexplained weight loss is a worrying symptom caused by lack of appetite and systemic effects of a malignant growth. However, weight loss is not as much a feature of colorectal cancer as it is of other cancers (e.g. oesophageal carcinoma).

- Anemia, causing dizziness, fatigue and palpitations. Clinically, there will be pallor and blood tests will confirm the low hemoglobin level.

Metastatic symptoms

- Liver metastases, causing :

- Blood clots in the veins and arteries, a paraneoplastic syndrome related to hypercoagulability of the blood (the blood is "thickened")

Risk factors

The lifetime risk of developing colon cancer in the United States is about 7%. Certain factors increase a person's risk of developing the disease.[2] These include:

- Age. The risk of developing colorectal cancer increases with age. Most cases occur in the 60s and 70s, while cases before age 50 are uncommon unless a family history of early colon cancer is present.

- Polyps of the colon, particularly adenomatous polyps, are a risk factor for colon cancer. The removal of colon polyps at the time of colonoscopy reduces the subsequent risk of colon cancer.

- History of cancer. Individuals who have previously been diagnosed and treated for colon cancer are at risk for developing colon cancer in the future. Women who have had cancer of the ovary, uterus, or breast are at higher risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Heredity:

- Family history of colon cancer, especially in a close relative before the age of 55 or multiple relatives

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) carries a near 100% risk of developing colorectal cancer by the age of 40 if untreated

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome

- Smoking. Smokers are more likely to die of colorectal cancer than non-smokers. An American Cancer Society study found that "Women who smoked were more than 40% more likely to die from colorectal cancer than women who never had smoked. Male smokers had more than a 30% increase in risk of dying from the disease compared to men who never had smoked."[3]

- Diet. Studies show that a diet high in red meat[4] and low in fresh fruit, vegetables, poultry and fish increases the risk of colorectal cancer. In June 2005, a study by the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition suggested that diets high in red and processed meat, as well as those low in fiber, are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Individuals who frequently eat fish showed a decreased risk.[1] However, other studies have cast doubt on the claim that diets high in fiber decrease the risk of colorectal cancer; rather, low-fiber diet was associated with other risk factors, leading to confounding.[5] The nature of the relationship between dietary fiber and risk of colorectal cancer remains controversial.

- Physical inactivity. People who are physically active are at lower risk of developing colorectal cancer.

- Virus. Exposure to some viruses (such as particular strains of human papilloma virus) may be associated with colorectal cancer.

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis offers a risk independent to ulcerative colitis

- Low levels of selenium.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease. [6] [7] About one percent of colorectal cancer patients have a history of chronic ulcerative colitis. The risk of developing colorectal cancer varies inversely with the age of onset of the colitis and directly with the extent of colonic involvement and the duration of active disease. Patients with colorectal Crohn's disease have a more than average risk of colorectal cancer, but less than that of patients with ulcerative colitis. [8]

- Environmental Factors. [6] Industrialized countries are at a relatively increased risk compared to less developed countries or countries that traditionally had high-fiber/low-fat diets. Studies of migrant populations have revealed a role for environmental factors, particularly dietary, in the etiology of colorectal cancers.

- Exogenous Hormones. The differences in the time trends in colorectal cancer in males and females could be explained by cohort effects in exposure to some sex-specific risk factor; one possibility that has been suggested is exposure to estrogens [9]. There is, however, little evidence of an influence of endogenous hormones on the risk of colorectal cancer. In contrast,there is evidence that exogenous estrogens such as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), tamoxifen, or oral contraceptives might be associated with colorectal tumors. [10]

- Alcohol. Drinking, especially heavily, may be a risk factor.

Alcohol

The WCRF panel report Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective finds the evidence "convincing" that alcoholic drinks increase the risk of colorectal cancer in men.[11]

The NIAAA reports that: "Epidemiologic studies have found a small but consistent dose-dependent association between alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer[12][13]even when controlling for fiber and other dietary factors.[14][15] Despite the large number of studies, however, causality cannot be determined from the available data."[16]

"Heavy alcohol use may also increase the risk of colorectal cancer" (NCI). One study found that "People who drink more than 30 grams of alcohol per day (and especially those who drink more than 45 grams per day) appear to have a slightly higher risk for colorectal cancer."[17][18] Another found that "The consumption of one or more alcoholic beverages a day at baseline was associated with approximately a 70% greater risk of colon cancer."[19][20][21]

One study found that "While there was a more than twofold increased risk of significant colorectal neoplasia in people who drink spirits and beer, people who drank wine had a lower risk. In our sample, people who drank more than eight servings of beer or spirits per week had at least a one in five chance of having significant colorectal neoplasia detected by screening colonoscopy.".[22]

Other research suggests that "to minimize your risk of developing colorectal cancer, it's best to drink in moderation."[16]

On its colorectal cancer page, the National Cancer Institute does not list alcohol as a risk factor[23]: however, on another page it states, "Heavy alcohol use may also increase the risk of colorectal cancer" [24]

Drinking may be a cause of earlier onset of colorectal cancer.[25]

Diagnosis, screening and monitoring

Colorectal cancer can take many years to develop and early detection of colorectal cancer greatly improves the chances of a cure. Therefore, screening for the disease is recommended in individuals who are at increased risk. There are several different tests available for this purpose.

- Digital rectal exam (DRE): The doctor inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum to feel for abnormal areas. It only detects tumors large enough to be felt in the distal part of the rectum but is useful as an initial screening test.

- Fecal occult blood test (FOBT): a test for blood in the stool. Two types of tests can be used for detecting occult blood in stools i.e. guaiac based (chemical test) and immunochemical. The sensitivity of immunochemical testing is superior to that of chemical testing without an unacceptable reduction in specifity. [26]

- Endoscopy:

- Sigmoidoscopy: A lighted probe (sigmoidoscope) is inserted into the rectum and lower colon to check for polyps and other abnormalities.

- Colonoscopy: A lighted probe called a colonoscope is inserted into the rectum and the entire colon to look for polyps and other abnormalities that may be caused by cancer. A colonoscopy has the advantage that if polyps are found during the procedure they can be immediately removed. Tissue can also be taken for biopsy.

In the United States, colonoscopy or FOBT plus sigmoidoscopy are the preferred screening options.

Other screening methods

- Double contrast barium enema (DCBE): First, an overnight preparation is taken to cleanse the colon. An enema containing barium sulfate is administered, then air is insufflated into the colon, distending it. The result is a thin layer of barium over the inner lining of the colon which is visible on X-ray films. A cancer or a precancerous polyp can be detected this way. This technique can miss the (less common) flat polyp.

- Virtual colonoscopy replaces X-ray films in the double contrast barium enema (above) with a special computed tomography scan and requires special workstation software in order for the radiologist to interpret. This technique is approaching colonoscopy in sensitivity for polyps. However, any polyps found must still be removed by standard colonoscopy.

- Standard computed axial tomography is an x-ray method that can be used to determine the degree of spread of cancer, but is not sensitive enough to use for screening. Some cancers are found in CAT scans performed for other reasons.

- Blood tests: Measurement of the patient's blood for elevated levels of certain proteins can give an indication of tumor load. In particular, high levels of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in the blood can indicate metastasis of adenocarcinoma. These tests are frequently false positive or false negative, and are not recommended for screening, it can be useful to assess disease recurrence.

- Genetic counseling and genetic testing for families who may have a hereditary form of colon cancer, such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

- Positron emission tomography (PET) is a 3-dimensional scanning technology where a radioactive sugar is injected into the patient, the sugar collects in tissues with high metabolic activity, and an image is formed by measuring the emission of radiation from the sugar. Because cancer cells often have very high metabolic rate, this can be used to differentiate benign and malignant tumors. PET is not used for screening and does not (yet) have a place in routine workup of colorectal cancer cases.

- Whole-Body PET imaging is the most accurate diagnostic test for detection of recurrent colorectal cancer, and is a cost-effective way to differentiate resectable from non-resectable disease. A PET scan is indicated whenever a major management decision depends upon accurate evaluation of tumour presence and extent.

- Stool DNA testing is an emerging technology in screening for colorectal cancer. Pre-malignant adenomas and cancers shed DNA markers from their cells which are not degraded during the digestive process and remain stable in the stool. Capture, followed by PCR amplifies the DNA to detectable levels for assay. Clinical studies have shown a cancer detection sensitivity of 71%-91%.[27]

Pathology

The pathology of the tumor is usually reported from the analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. A pathology report will usually contain a description of cell type and grade. The most common colon cancer cell type is adenocarcinoma which accounts for 95% of cases. Other, rarer types include lymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Cancers on the right side (ascending colon and cecum) tend to be exophytic, that is, the tumour grows outwards from one location in the bowel wall. This very rarely causes obstruction of feces, and presents with symptoms such as anemia. Left-sided tumours tend to be circumferential, and can obstruct the bowel much like a napkin ring.

Histopathology: Adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from glandular epithelium of the colorectal mucosa. It invades the wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa and thence the muscularis propria. Tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Sometimes, tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus, which invades the interstitium producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces) - mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma, poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the periphery - "signet-ring cell." Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism, and mucosecretion of the predominant pattern, adenocarcinoma may present three degrees of differentiation: well, moderately, and poorly differentiated. [28]

Staging

Colon cancer staging is an estimate of the amount of penetration of a particular cancer. It is performed for diagnostic and research purposes, and to determine the best method of treatment. The systems for staging colorectal cancers largely depend on the extent of local invasion, the degree of lymph node involvement and whether there is distant metastasis.

Definitive staging can only be done after surgery has been performed and pathology reports reviewed. An exception to this principle would be after a colonoscopic polypectomy of a malignant pedunculated polyp with minimal invasion. Preoperative staging of rectal cancers may be done with endoscopic ultrasound. Adjuncts to staging of metastasis include Abdominal Ultrasound, CT, PET Scanning, and other imaging studies.

Dukes system

Dukes classification, first proposed by Dr Cuthbert E. Dukes in 1932, identifies the stages as:[29]

- A - Tumour confined to the intestinal wall

- B - Tumour invading through the intestinal wall

- C - With lymph node(s) involvement (this is further subdivided into C1 lymph node involvement where the apical node is not involved and C2 where the apical lymph node is involved)

- D - With distant metastasis

TNM system

The most common current staging system is the TNM (for tumors/nodes/metastases) system, though many doctors still use the older Dukes system. The TNM system assigns a number[30]:

- T - The degree of invasion of the intestinal wall

- T0 - no evidence of tumor

- Tis- cancer in situ (tumor present, but no invasion)

- T1 - invasion through submucosa into lamina propria (basement membrane invaded)

- T2 - invasion into the muscularis propria (i.e. proper muscle of the bowel wall)

- T3 - invasion through the subserosa

- T4 - invasion of surrounding structures (e.g. bladder) or with tumour cells on the free external surface of the bowel

- N - the degree of lymphatic node involvement

- N0 - no lymph nodes involved

- N1 - one to three nodes involved

- N2 - four or more nodes involved

- M - the degree of metastasis

- M0 - no metastasis

- M1 - metastasis present

AJCC stage groupings

The stage of a cancer is usually quoted as a number I, II, III, IV derived from the TNM value grouped by prognosis; a higher number indicates a more advanced cancer and likely a worse outcome.

- Stage 0

- Tis, N0, M0

- Stage I

- T1, N0, M0

- T2, N0, M0

- Stage IIA

- T3, N0, M0

- Stage IIB

- T4, N0, M0

- Stage IIIA

- T1, N1, M0

- T2, N1, M0

- Stage IIIB

- T3, N1, M0

- T4, N1, M0

- Stage IIIC

- Any T, N2, M0

- Stage IV

- Any T, Any N, M1

Pathogenesis

Colorectal cancer is a disease originating from the epithelial cells lining the gastrointestinal tract. Hereditary or somatic mutations in specific DNA sequences, among which are included DNA replication or DNA repair genes[31], and also the APC, K-Ras, NOD2 and p53[32] genes, lead to unrestricted cell division. The exact reason why (and whether) a diet high in fiber might prevent colorectal cancer remains uncertain. Chronic inflammation, as in inflammatory bowel disease, may predispose patients to malignancy.

Treatment

The treatment depends on the staging of the cancer. When colorectal cancer is caught at early stages (with little spread) it can be curable. However when it is detected at later stages (when distant metastases are present) it is less likely to be curable.

Surgery remains the primary treatment while chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may be recommended depending on the individual patient's staging and other medical factors.

Surgery

Surgeries can be categorised into curative, palliative, bypass, fecal diversion, or open-and-close.

Curative Surgical treatment can be offered if the tumor is localized.

- Very early cancer that develops within a polyp can often be cured by removing the polyp (i.e., polypectomy) at the time of colonoscopy.

- In colon cancer, a more advanced tumor typically requires surgical removal of the section of colon containing the tumor with sufficient margins, and radical en-bloc resection of mesentery and lymph nodes to reduce local recurrence (i.e., colectomy). If possible, the remaining parts of colon are anastomosed together to create a functioning colon. In cases when anastomosis is not possible, a stoma (artificial orifice) is created.

- Curative surgery on rectal cancer includes total mesorectal excision (lower anterior resection) or abdominoperineal excision.

In case of multiple metastases, palliative (non curative) resection of the primary tumor is still offered in order to reduce further morbidity caused by tumor bleeding, invasion, and its catabolic effect. Surgical removal of isolated liver metastases is, however, common and may be curative in selected patients; improved chemotherapy has increased the number of patients who are offered surgical removal of isolated liver metastases.

If the tumor invaded into adjacent vital structures which makes excision technically difficult, the surgeons may prefer to bypass the tumor (ileotransverse bypass) or to do a proximal fecal diversion through a stoma.

The worst case would be an open-and-close surgery, when surgeons find the tumor unresectable and the small bowel involved; any more procedures would do more harm than good to the patient. This is uncommon with the advent of laparoscopy and better radiological imaging. Most of these cases formerly subjected to "open and close" procedures are now diagnosed in advance and surgery avoided.

Laparoscopic-assisted colectomy is a minimally-invasive technique that can reduce the size of the incision and may reduce post-operative pain.

As with any surgical procedure, colorectal surgery may result in complications including

- wound infection, Dehiscence (bursting of wound) or hernia

- anastomosis breakdown, leading to abscess or fistula formation, and/or peritonitis

- bleeding with or without hematoma formation

- adhesions resulting in bowel obstruction (especially small bowel)

- adjacent organ injury; most commonly to the small intestine, ureters, spleen, or bladder

- Cardiorespiratory complications such as myocardial infarction, pneumonia, arrythmia, pulmonary embolism etc

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is used to reduce the likelihood of metastasis developing, shrink tumor size, or slow tumor growth. Chemotherapy is often applied after surgery (adjuvant), before surgery (neo-adjuvant), or as the primary therapy (palliative). The treatments listed here have been shown in clinical trials to improve survival and/or reduce mortality rate and have been approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration. In colon cancer, chemotherapy after surgery is usually only given if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes (Stage III).

- Adjuvant (after surgery) chemotherapy. One regimen involves the combination of infusional 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX)

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or Capecitabine (Xeloda)

- Leucovorin (LV, Folinic Acid)

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

- Chemotherapy for metastatic disease. Commonly used first line chemotherapy regimens involve the combination of infusional 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) with bevacizumab or infusional 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) with bevacizumab

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or Capecitabine

- UFT or Tegafur-uracil

- Leucovorin (LV, Folinic Acid)

- Irinotecan (Camptosar)

- Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin)

- Bevacizumab (Avastin)

- Cetuximab (Erbitux)

- Panitumumab (Vectibix)

- In clinical trials for treated/untreated metastatic disease. [2]

- Bortezomib (Velcade)

- Oblimersen (Genasense, G3139)

- Gefitinib and Erlotinib (Tarceva)

- Topotecan (Hycamtin)

Radiation therapy

Radiotherapy is not used routinely in colon cancer, as it could lead to radiation enteritis, and it is difficult to target specific portions of the colon. It is more common for radiation to be used in rectal cancer, since the rectum does not move as much as the colon and is thus easier to target. Indications include:

- Colon cancer

- pain relief and palliation - targeted at metastatic tumor deposits if they compress vital structures and/or cause pain

- Rectal cancer

- neoadjuvant - given before surgery in patients with tumors that extend outside the rectum or have spread to regional lymph nodes, in order to decrease the risk of recurrence following surgery or to allow for less invasive surgical approaches (such as a low anterior resection instead of an abdomino-perineal resection)

- adjuvant - where a tumor perforates the rectum or involves regional lymph nodes (AJCC T3 or T4 tumors or Duke's B or C tumors)

- palliative - to decrease the tumor burden in order to relieve or prevent symptoms

Sometimes chemotherapy agents are used to increase the effectiveness of radiation by sensitizing tumor cells if present.

Immunotherapy

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is being investigated as an adjuvant mixed with autologous tumor cells in immunotherapy for colorectal cancer.[33]

Vaccine

In November 2006, it was announced that a vaccine had been developed and tested with very promising results.[34] The new vaccine, called TroVax, works in a totally different way to existing treatments by harnessing the patient's own immune system to fight the disease. Experts say this suggests that gene therapy vaccines could prove an effective treatment for a whole range of cancers. Oxford BioMedica is a British spin-out from Oxford University specialising in the development of gene-based treatments. Phase III trials are underway for renal cancers and planned for colon cancers.[35]

Treatment of liver metastases

According to the American Cancer Society statistics in 2006,[3] over 20% of patients present with metastatic (stage IV) colorectal cancer at the time of diagnosis, and up to 25% of this group will have isolated liver metastasis that is potentially resectable. Lesions which undergo curative resection have demonstrated 5-year survival outcomes now exceeding 50%.[36]

Resectability of a liver metastasis is determined using preoperative imaging studies (CT or MRI), intraoperative ultrasound, and by direct palpation and visualization during resection. Lesions confined to the right lobe are amenable to en bloc removal with a right hepatectomy (liver resection) surgery. Smaller lesions of the central or left liver lobe may sometimes be resected in anatomic "segments", while large lesions of left hepatic lobe are resected by a procedure called hepatic trisegmentectomy. Treatment of lesions by smaller, non-anatomic "wedge" resections is associated with higher recurrence rates. Some lesions which are not initially amenable to surgical resection may become candidates if they have significant responses to preoperative chemotherapy or immunotherapy regimens. Lesions which are not amenable to surgical resection for cure can be treated with modalities including radio-frequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, and chemoembolization.

Patients with colon cancer and metastatic disease to the liver may be treated in either a single surgery or in staged surgeries (with the colon tumor traditionally removed first) depending upon the fitness of the patient for prolonged surgery, the difficulty expected with the procedure with either the colon or liver resection, and the comfort of the surgery performing potentially complex hepatic surgery.

Poor prognostic factors of patients with liver metastasis include:

- Synchronous (diagnosed simultaneously) liver and primary colorectal tumors

- A short time between detecting the primary cancer and subsequent development of liver mets

- Multiple metastatic lesions

- High blood levels of the tumor marker, carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA), in the patient prior to resection

- Larger size metastatic lesions

Support therapies

Cancer diagnosis very often results in an enormous change in the patient's psychological wellbeing. Various support resources are available from hospitals and other agencies which provide counseling, social service support, cancer support groups, and other services. These services help to mitigate some of the difficulties of integrating a patient's medical complications into other parts of their life.

Prognosis

Survival is directly related to detection and the type of cancer involved. Survival rates for early stage detection is about 5 times that of late stage cancers. CEA level is also directly related to the prognosis of disease, since its level correlates with the bulk of tumor tissue.

Follow-up

The aims of follow-up are to diagnose in the earliest possible stage any metastasis or tumors that develop later but did not originate from the original cancer (metachronous lesions).

The U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology provide guidelines for the follow-up of colon cancer.[37][38] A medical history and physical examination are recommended every 3 to 6 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 5 years. Carcinoembryonic antigen blood level measurements follow the same timing, but are only advised for patients with T2 or greater lesions who are candidates for intervention. A CT-scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis can be considered annually for the first 3 years for patients who are at high risk of recurrence (for example, patients who had poorly differentiated tumors or venous or lymphatic invasion) and are candidates for curative surgery (with the aim to cure). A colonoscopy can be done after 1 year, except if it could not be done during the initial staging because of an obstructing mass, in which case it should be performed after 3 to 6 months. If a villous polyp, polyp >1 centimeter or high grade dysplasia is found, it can be repeated after 3 years, then every 5 years. For other abnormalities, the colonoscopy can be repeated after 1 year.

Routine PET or ultrasound scanning, chest X-rays, complete blood count or liver function tests are not recommended.[37][38] These guidelines are based on recent meta-analyses showing that intensive surveillance and close follow-up can reduce the 5-year mortality rate from 37% to 30%.[39][40][41]

Prevention

Most colorectal cancers should be preventable, through increased surveillance, improved lifestyle, and, probably, the use of dietary chemopreventative agents.

Surveillance

Most colorectal cancer arise from adenomatous polyps. These lesions can be detected and removed during colonoscopy. Studies show this procedure would decrease by > 80% the risk of cancer death, provided it is started by the age of 50, and repeated every 5 or 10 years.[42]

As per current guidelines under National Comprehensive Cancer Network, in average risk individuals with negative family history of colon cancer and personal history negative for adenomas or Inflammatory Bowel diseases, flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years with fecal occult blood testing annually or double contrast barium enema are other options acceptable for screening rather than colonoscopy every 10 years (which is currently the Gold-Standard of care).

Lifestyle & Nutrition

The comparison of colorectal cancer incidence in various countries strongly suggests that sedentarity, overeating (i.e., high caloric intake), and perhaps a diet high in meat (red or processed) could increase the risk of colorectal cancer. In contrast, a healthy body weight, physical fitness, and good nutrition decreases cancer risk in general. Accordingly, lifestyle changes could decrease the risk of colorectal cancer as much as 60-80%.[43]

A high intake of dietary fiber (from eating fruits, vegetables, cereals, and other high fiber food products) has, until recently, been thought to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma. In the largest study ever to examine this theory (88,757 subjects tracked over 16 years), it has been found that a fiber rich diet does not reduce the risk of colon cancer. [44] A 2005 meta-analysis study further supports these findings.[45]

The Harvard School of Public Health states: "Health Effects of Eating Fiber: Long heralded as part of a healthy diet, fiber appears to reduce the risk of developing various conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, diverticular disease, and constipation. Despite what many people may think, however, fiber probably has little, if any effect on colon cancer risk." [46]

Chemoprevention

More than 200 agents, including the above cited phytochemicals, and other food components like calcium or folic acid (a B vitamin), and NSAIDs like aspirin, are able to decrease carcinogenesis in pre-clinical development models: Some studies show full inhibition of carcinogen-induced tumours in the colon of rats. Other studies show strong inhibition of spontaneous intestinal polyps in mutated mice (Min mice). Chemoprevention clinical trials in human volunteers have shown smaller prevention, but few intervention studies have been completed today. Calcium, aspirin and celecoxib supplements, given for 3 to 5 years after the removal of a polyp, decreased the recurrence of polyps in volunteers (by 15-40%). The "chemoprevention database" shows the results of all published scientific studies of chemopreventive agents, in people and in animals.[47]

Aspirin chemoprophylaxis

Aspirin should not be taken routinely to prevent colorectal cancer, even in people with a family history of the disease, because the risk of bleeding and kidney failure from high dose aspirin (300mg or more) outweigh the possible benefits.[48]

A clinical practice guideline of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against taking aspirin (grade D recommendation).[49] The Task Force acknowledged that aspirin may reduce the incidence of colorectal cancer, but "concluded that harms outweigh the benefits of aspirin and NSAID use for the prevention of colorectal cancer". A subsequent meta-analysis concluded "300 mg or more of aspirin a day for about 5 years is effective in primary prevention of colorectal cancer in randomised controlled trials, with a latency of about 10 years".[50] However, long-term doses over 81 mg per day may increase bleeding events.[51]

Calcium

A meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration of randomized controlled trials published through 2002 concluded "Although the evidence from two RCTs suggests that calcium supplementation might contribute to a moderate degree to the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps, this does not constitute sufficient evidence to recommend the general use of calcium supplements to prevent colorectal cancer.".[52] Subsequently, one randomized controlled trial by the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) reported negative results.[53] A second randomized controlled trial reported reduction in all cancers, but had insufficient colorectal cancers for analysis.[54]

Mathematical modeling

Colorectal cancer has been the subject of mathematical modeling for many years.[55] For a comprehensive overview of current computational approaches on colorectal cancer see the Integrative Biology web page.

Famous people diagnosed with colorectal cancer

- Carolyn Jones, actress and comedienne know for playing Morticia Addams in "The Addams Family". Diagnosed with colon cancer in 1982, died one year later in 1983.

- Lynn Faulds Wood, former BBC Watchdog presenter, survived advanced bowel cancer and founded the charities Beating Bowel Cancer and Lynn's Bowel Cancer Campaign. [56]

- Tony Snow died July 12, 2008 at the age of 53. [4]

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg

- Tammy Faye Messner died July 20, 2007

- Audrey Hepburn died January 20, 1993 [5]

- Lois Maxwell, a Canadian actress, known for originating the role of Miss Moneypenny in the James Bond franchise (which she played in fourteen films), died September 29 2007

- H. P. Lovecraft, horror writer

- Harold Wilson [6]

- Pope John Paul II [7]

- Ronald Reagan [8]

- Elizabeth Montgomery, American Actress (died at age 62; died 8 weeks after being diagnosed with colon cancer. see [9])

- Charles Schulz, Creator of Peanuts (died at age 77; died 60 days after being diagnosed with colon cancer) [10].

- Lillian Board, British athlete

- Malcolm Marshall, Legendary West Indian and Hampshire Cricketer [11]

- Achille-Claude Debussy, Famous French composer [12]

- Bobby Moore, 1966 England World cup winning captain (died at age 51; died 2 years after being diagnosed with colon cancer) [13]

- Babe Didrikson Zaharias, Legendary American athlete [14]

- Joel Siegel, movie critic and Host of Good Morning America (died at age 64; died 10 years after being diagnosed with colon cancer)

- Eric Turner, second player taken in the 1991 NFL Draft

- Walter Matthau, American actor, had metastatic colon cancer, but died of heart disease on July 1, 2000, aged 79

- Vince Lombardi, legendary coach of the Green Bay Packers, died of metastatic colon cancer

- Rod Roddy, previous announcer for The Price Is Right (died at age 66; died 2 years after being diagnosed with colon cancer)

- George David Low, American aerospace executive and a former NASA astronaut; died 2008

- Corazon Aquino, Former president of the Philippines. [15]

- Jack Lemmon, American actor, died of colon cancer (and bladder cancer) on 27 June 2001, aged 76.

- Sharon Osbourne, British reality TV star and talent show judge, diagnosed with colon cancer in July 2002, aged 49. She is now 55, and is believed to have recovered.

- Jay Monahan, husband of news anchor Katie Couric, died of colon cancer in 1998 at the age of 42; Couric became a vocal spokesperson for colon cancer and an increase in screening rates is attributed to publicity generated by her.

- Dick Dale Legendary surf guitarist whose cancer has recurred as of 2008.

See also

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

- Diet and cancer

- Bowel & Cancer Research

References

- ↑ "Cancer". World Health Organization (February 2006). Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Levin KE, Dozois RR. Department of Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota 55905 Epidemiology of large bowel cancer. World J Surg. 1991 Sep-Oct;15(5):562-7. PMID 1949852.

- ↑ American Cancer Society Smoking Linked to Increased Colorectal Cancer Risk - New Study Links Smoking to Increased Colorectal Cancer Risk 2000-12-06

- ↑ Chao A, Thun MJ, Connell CJ, McCullough ML, Jacobs EJ, Flanders WD, Rodriguez C, Sinha R, Calle EE. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA 2005;293:172-82. PMID 15644544.

- ↑ Park Y, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Bergkvist L, Berrino F et al. Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. JAMA 2005;294:2849-57. PMID 16352792.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gregory L. Brotzman and Russell G. Robertson (2006). "Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors". Colorectal Cancer. Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Jerome J. DeCosse, MD; George J. Tsioulias, MD; Judish S. Jacobson, MPH (February 1994) (PDF). Colorectal cancer: detection, treatment, and rehabilitation. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/reprint/44/1/27.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Hamilton SR. Colorectal Carcinoma in patients with Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology 1985; 89; 398-407

- ↑ DO SANTOS SILVA I. ; SWERDLOW A. J. (2007). Sex differences in time trends of colorectal cancer in England and Wales: the possible effect of female hormonal factors.. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=2995435.

- ↑ Beral V, Banks E, Reeves G, Appleby P. Use of HRT and the subsequent risk of cancer. Imperial Cancer Research Fund Cancer Epidemiology Unit, Oxford, UK. 1999;4(3):191-210; discussion 210-5. PMID 10695959.

- ↑ WCRF Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective

- ↑ Longnecker, M.P. Alcohol consumption in relation to risk of cancers of the breast and large bowel. Alcohol Health & Research World 16(3)':223-229, 1992.

- ↑ Longnecker, M.P.; Orza, M.J.; Adams, M.E.; Vioque, J.; and Chalmers, T.C. A meta-analysis of alcoholic beverage consumption in relation to risk of colorectal cancer Cancer Causes and Control 1(1):59-68, 1990.

- ↑ Kune, S.; Kune, G.A.; and Watson, L.F. Case-control study of alcoholic beverages as etiological factors: The Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study Nutrition and Cancer 9(1):43-56, 1987.

- ↑ Potter, J.D., and McMichael, A.J. Diet and cancer of the colon and rectum: A case-control study Journal of the National Cancer Institute 76(4):557-569, 1986.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Alcohol and Cancer - Alcohol Alert No. 21-1993

- ↑ Alcohol Consumption and the Risk for Colorectal Cancer 20 April 2004

- ↑ Alcohol Intake and Colorectal Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 8 Cohort Studies

- ↑ Boston University "Alcohol May Increase the Risk of Colon Cancer"

- ↑ Su LJ, Arab L. Alcohol consumption and risk of colon cancer: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-Up Study. Nutr and Cancer. 2004;50(2):111–119.

- ↑ Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Ritz J, van den Brandt PA, Colditz GA, Folsom AR, Freudenheim JL, Giovannucci E, Goldbohm RA, Graham S, Holmberg L, Kim DH, Malila N, Miller AB, Pietinen P, Rohan TE, Sellers TA, Speizer FE, Willett WC, Wolk A, Hunter DJ Alcohol intake and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies Ann Intern Med 2004 Apr 20;140(8):603-13

- ↑ Joseph C. Anderson, Zvi Alpern, Gurvinder Sethi, Catherine R. Messina, Carole Martin, Patricia M. Hubbard, Roger Grimson, Peter F. Ells, and Robert D. Shaw Prevalence and Risk of Colorectal Neoplasia in Consumers of Alcohol in a Screening Population Am J Gastroenterol Volume 100 Issue 9 Page 2049 Date September 2005

- ↑ Colorectal Cancer: Who's at Risk? (National Institutes of Health: National Cancer Institute)

- ↑ National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Trends Progress Report Alcohol Consumption

- ↑ Brown, Anthony J. Alcohol, tobacco, and male gender up risk of earlier onset colorectal cancer

- ↑ Weitzel JN: Genetic cancer risk assessment. Putting it all together. Cancer 86:2483,1999. PMID 10630174

- ↑ B. Greenwald (2006). "The DNA Stool Test - An Emerging Technology in Colorectal Cancer Screening".

- ↑ Pathology atlas (in Romanian)

- ↑ Dukes CE. The classification of cancer of the rectum. Journal of Pathological Bacteriology 1932;35:323.

- ↑ Wittekind, Ch; Sobin, L. H. (2002). TNM classification of malignant tumours. New York: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 0-471-22288-7.

- ↑ Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M (1993). "Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis". Nature 363 (6429): 558–61. doi:. PMID 8505985.

- ↑ Srikumar Chakravarthi, Baba Krishnan, Malathy Madhavan. Apoptosis and expression of p53 in colorectal neoplasms. Indian J Med Res 111,1999;95-102

- ↑ Mosolits S, Nilsson B, Mellstedt H. Towards therapeutic vaccines for colorectal carcinoma: a review of clinical trials., Expert Rev. Vaccines, 2005;4:329-50. PMID 16026248.

- ↑ Wheldon, Julie. Vaccine for kidney and bowel cancers 'within three years' The Daily Mail 2006-11-13

- ↑ Vaccine Works With Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer (Reuters) 2007-08-13

- ↑ Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, Garden OJ, Poston GJ, Rees M (April 2006). "Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies". Br. J. Cancer 94 (7): 982–99. doi:. PMID 16538219.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology - Colon Cancer (version 1, 2008: September 19, 2007).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Desch CE, Benson AB 3rd, Somerfield MR, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology (2005). "Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline" (PDF). J Clin Oncol 23 (33): 8512–9. doi:. PMID 16260687. http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/reprint/JCO.2005.04.0063v1.pdf.

- ↑ Jeffery M, Hickey BE, Hider PN (2002). "Follow-up strategies for patients treated for non-metastatic colorectal cancer". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. doi:. CD002200. http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD002200/frame.html.

- ↑ Renehan AG, Egger M, Saunders MP, O'Dwyer ST (2002). "Impact on survival of intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials". BMJ 324 (7341): 831–8. doi:. PMID 11934773. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/324/7341/813.

- ↑ Figueredo A, Rumble RB, Maroun J, et al; Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario's Program in Evidence-based Care. (2003). "Follow-up of patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer: a practice guideline.". BMC Cancer 3: 26. doi:.

- ↑ Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF, Ackroyd F, Shike M, Kurtz RC, Hornsby-Lewis L, Gerdes H, Stewart ET, The National Polyp Study Workgroup. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1977-81. PMID 8247072.

- ↑ Cummings, JH; Bingham SA (1998). "Diet and the prevention of cancer". BMJ: 1636–40. PMID 9848907. http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/.

- ↑ Fuchs, C. S. (1999). "Dietary Fiber and the Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Adenoma in Women". New England Journal of Medicine 340 (340): 169–76. doi:. PMID 9895396. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/340/3/169.

- ↑ Baron, J. A. (2005). "Dietary Fiber and Colorectal Cancer: An Ongoing Saga". Journal of the American Medical Association 294 (294(22)): 2904–2906. doi:. PMID 16352792.

- ↑ "Health Effects of Eating Fiber".

- ↑ "Colorectal Cancer Prevention: Chemoprevention Database". Retrieved on 2007-08-23.

- ↑ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2007-03-05). "Task Force Recommends Against Use of Aspirin and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs to Prevent Colorectal Cancer". United States Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved on 2007-05-07.

- ↑ "Routine aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the primary prevention of colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (5): 361–4. 2007. pmid=17339621. PMID 17339621

- ↑ Flossmann E, Rothwell PM (2007). "Effect of aspirin on long-term risk of colorectal cancer: consistent evidence from randomised and observational studies". Lancet 369 (9573): 1603–13. doi:. PMID 17499602. PMID 17499602

- ↑ Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR (2007). "Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review". JAMA 297 (18): 2018–24. doi:. PMID 17488967. PMID 17488967

- ↑ Weingarten MA, Zalmanovici A, Yaphe J (2005). "Dietary calcium supplementation for preventing colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003548. doi:. PMID 16034903.

- ↑ Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, et al (2006). "Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 354 (7): 684–96. doi:. PMID 16481636.

- ↑ Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP (2007). "Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85 (6): 1586–91. PMID 17556697. http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/full/85/6/1586.

- ↑ van Leeuwen I, Byrne H, Jensen O, King J (2006). "Crypt dynamics and colorectal cancer: advances in mathematical modelling.". Cell Prolif 39 (3): 157–81. doi:. PMID 16671995.Full text

- ↑ Lynn's Bowel Cancer Campaign|http://www.bowelcancer.tv/cgi-bin/page.pl?page=LynnsStory&accessability=no

External links

- Colorectal cancer at the Open Directory Project

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||