Colonoscopy

| Intervention: Colonoscopy |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| ICD-10 code: | ||

| ICD-9 code: | 45.23 | |

| MeSH | D003113 | |

| Other codes: | ||

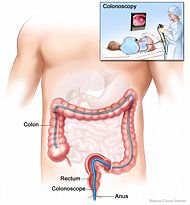

Colonoscopy is the endoscopic examination of the large colon and the distal part of the small bowel with a CCD camera or a fiber optic camera on a flexible tube passed through the anus. It may provide a visual diagnosis (e.g. ulceration, polyps) and grants the opportunity for biopsy or removal of suspected lesions. Virtual colonoscopy, which uses 2D and 3D imagery reconstructed from computed tomography (CT) scans or from nuclear magnetic resonance (MR) scans, is also possible, as a totally non-invasive medical test, although it is not standard and still under investigation regarding its diagnostic abilities. Furthermore, virtual colonoscopy does not allow for therapeutic maneuvers such as polyp/tumor removal or biopsy nor visualization of lesions smaller than 5 millimeters. If a growth or polyp is detected using CT colonography, a standard colonoscopy would still need to be performed. Colonoscopy can remove polyps as small as one millimeter or less. Once polyps are removed, they can be studied with the aid of a microscope to determine if they are precancerous or not. Colonoscopy is similar to but not the same as sigmoidoscopy. The difference between colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy is related to which parts of the colon each can examine. Sigmoidoscopy allows doctors to view only the final two feet of the colon, while colonoscopy allows an examination of the entire colon, which measures four to five feet in length. Often a sigmoidoscopy is used as a screening procedure for a full colonoscopy. In many instances a sigmoidoscopy is performed in conjunction with a fecal occult blood test (FOBT), which can detect the formation of cancerous cells throughout the colon.

Contents |

Reasons for Procedure

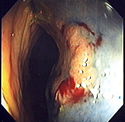

Indications for colonoscopy include gastrointestinal hemorrhage, unexplained changes in bowel habit or suspicion of malignancy. Colonoscopies are often used to diagnose colon cancer, but are also frequently used to diagnose inflammatory bowel disease. In older patients (sometimes even younger ones) an unexplained drop in hematocrit (one sign of anemia) is an indication to do a colonoscopy, usually along with an EGD (esophagogastroduodenoscopy), even if no obvious blood has been seen in the stool (feces).

Fecal occult blood is a quick test which can be done to test for microscopic traces of blood in the stool. A positive test is almost always an indication to do a colonoscopy. In most cases the positive result is just due to hemorrhoids; however, it can also be due to diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis), colon cancer, or polyps. However--since its development by Dr. Hiromi Shinya in the 1960s--polypectomy has become a routine part of colonoscopy, allowing for quick and simple removal of polyps without invasive surgery.[1]

Due to the high mortality associated with colon cancer and the high effectivity and low risks associated with colonoscopy, it is now also becoming a routine screening test for people 50 years of age or older. Subsequent rescreenings are then scheduled based on the initial results found, with a five- or ten-year recall being common for colonoscopies that produce normal results. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (September 18, 2008) has found that among people who have had an initial colonoscopy that found no polyps, the risk of developing colorectal cancer within five years is extremely low. Therefore, there's no need for those people to have another colonoscopy sooner than five years after the first screening.[2][3] In July 2007, Njemanze and colleagues used high-frequency ultrasound to detect echogenic, floaters-associated parasites such as G.lamblia and E.histolytica in the duodenum (ultrasound duodenography) and colon (ultrasound colonography).

Procedure

Preparation

The colon must be free of solid matter for the test to be performed properly. For one to three days, the patient is required to follow a low fibre or clear-fluid only diet. Examples of clear fluids are apple juice, bouillon, artificially flavored lemon-lime soda or sports drink, and of course water. It is very important that the patient remains hydrated. Orange juice, prune juice, and milk containing fibre, are banned from the list, as are liquids dyed red, orange, purple, or brown, such as cola. However, in most cases black coffee is allowed. The day before the colonoscopy, the patient is either given a laxative preparation (such as Bisacodyl, phospho soda, sodium picosulfate, or sodium phosphate and/or magnesium citrate) and large quantities of fluid or whole bowel irrigation is performed using a solution of polyethylene glycol and electrolytes.

Since the goal of the preparation is to clear the colon of solid matter, the patient should plan to spend the day at home in comfortable surroundings with ready access to toilet facilities. The patient may also want to have at hand moist toilettes or a bidet for cleaning the anus. A soothing salve such as petroleum jelly applied after cleaning the anus will improve patient comfort.

The patient may be asked to skip aspirin and aspirin-like products such as salicylate, ibuprofen, and similar medications for up to ten days before the procedure to avoid the risk of bleeding if a polypectomy is performed during the procedure. A blood test may be performed before the procedure.[4][5]

The investigation

During the procedure the patient is often given sedation intravenously, employing agents such as midazolam or fentanyl. Although meperidine (Demerol) may be used as an alternative to fentanyl, the concern of seizures has relegated this agent to second choice for sedation behind the combination of midazolam and fentanyl. The average person will receive a combination of these two drugs, usually between 1-4 mg IV midazolam, and 25 to 100 µg IV fentanyl. Sedation practices vary between practitioners and nations; in some clinics in Norway, sedation is rarely administered.[6][7] Some endocoscopists are experimenting with, or routinely use, alternative or additional methods such as nitrous oxide[8][9] and propofol,[10] which have advantages and disadvantages relating to recovery time (particularly the duration of amnesia after the procedure is complete), patient experience, and the degree of supervision needed for safe administration. This sedation is called "twilight anesthesia" and for some patients it doesn't take and they are indeed awake for the procedure and watch the inside of their colon on the color monitor.

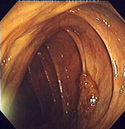

The first step is usually a digital rectal examination, to examine the tone of the sphincter and to determine if preparation has been adequate. The endoscope is then passed though the anus up the rectum, the colon (sigmoid, descending, transverse and ascending colon, the cecum), and ultimately the terminal ileum. The endoscope has a movable tip and multiple channels for instrumentation, air, suction and light. The bowel is occasionally insufflated with air to maximize visibility. Biopsies are frequently taken for histology.

In most experienced hands, the endoscope is advanced to the junction of where the colon and small bowel join up (cecum) in under 10 minutes in 95% of cases. Due to tight turns and redundancy in areas of the colon that are not "fixed", loops may form in which advancement of the endoscope creates a "bowing" effect that causes the tip to actually retract. These loops often result in discomfort due to stretching of the colon and its associated mesentery. Maneuvers to "reduce" or remove the loop include pulling the endoscope backwards while torquing the instrument. Alternatively, body position changes and abdominal support from external hand pressure can often "straighten" the endoscope to allow the scope to move forward. In a minority of patients, looping is often cited as a cause for an incomplete examination. Usage of alternative instruments leading to completion of the examination has been investigated, including use of pediatric colonscope, push enteroscope and upper GI endoscope variants.[11]

For screening purposes, a closer visual inspection is then often performed upon withdrawal of the endoscope over the course of 20 to 25 minutes. Lawsuits over missed cancerous lesions have prompted recent institutions to better document withdrawal time as rapid withdrawal times may be a source of potential medical legal liability.[12] This is often a real concern in private practice settings where high throughput of cases have been postulated as a financial incentive to complete colonoscopies as quickly as possible.

Suspicious lesions may be cauterized, treated with laser light or cut with an electric wire for purposes of biopsy or complete removal polypectomy. Medication can be injected, e.g. to control bleeding lesions. On average, the procedure takes 20-30 minutes, depending on the indication and findings. With multiple polypectomies or biopsies, procedure times may be longer. As mentioned above, anatomic considerations may also affect procedure times.

After the procedure, some recovery time is usually allowed to let the sedative wear off. Outpatient recovery time can take an estimate of 30-60 minutes. Most facilities require that patients have a person with them to help them home afterwards (again, depending on the sedation method used).

One very common aftereffect from the procedure is a bout of flatulence and minor wind pain caused by air insufflation into the colon during the procedure.

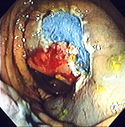

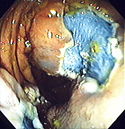

An advantage of colonoscopy over x-ray imaging or other, less invasive tests, is the ability to perform therapeutic interventions during the test. A polyp is a growth of excess of tissue that can develop into cancer. If a polyp is found, for example, it can be removed by one of several techniques. A snare can be placed around a polyp for removal. Even if the polyp is flat on the surface it can often be removed. For example, the following show a polyp removed in stages:

| Polyp is identified | A sterile solution is injected under the polyp to lift it away from deeper tissues. | A portion of the polyp is now removed. | The polyp is fully removed. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Risks

This procedure has a low (0.35%) risk of serious complications.[13][14]

The most serious complication generally is a tear or hole in the lining of the colon called a gastrointestinal perforation, which is life-threatening and requires immediate major surgery for repair; however, the rate of perforation is less than 1 in 2000 colonoscopies.

Bleeding complications may be treated immediately during the procedure by cauterization via the instrument. Delayed bleeding may also occur at the site of polyp removal up to a week after the procedure and a repeat procedure can then be performed to treat the bleeding site. Even more rarely, splenic rupture can occur after colonoscopy because of adhesions between the colon and the spleen.

As with any procedure involving anaesthesia, other complications would include cardiopulmonary complications such as temporary drop in blood pressure and oxygen saturation, usually the result of overmedication and easily reversed. In rare cases, more serious cardiopulmonary events such as a heart attack, stroke, or even death may occur; these are extremely rare except in critically ill patients with multiple risk factors.

Oral sodium phosphates for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy carry a risk of acute renal failure under the form of phosphate nephropathy.[15]

On very rare occasions, intracolonic explosion may occur.

References

- ↑ Sivak, Jr., Michael V. (2004-12). "Polypectomy: Looking Back". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 60 (6): 977–982. doi:. ISSN 1097-6779. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016510704023806.

- ↑ "Five-Year Risk of Colorectal Neoplasia after Negative Screening Colonoscopy.". N Engl J Med 359: 1218-1224. 2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0803597. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/359/12/1218. Retrieved on 2008-09-17.

- ↑ No Need to Repeat Colonoscopy Until 5 Years After First Screening Newswise, Retrieved on September 17, 2008.

- ↑ Decker, Joe (15 November 2006). "Preparation: Diet" (Blog). Colonoscopy Blog. Blogger.com. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ "Colyte/Trilyte Colonoscopy Preparation" (PDF). Palo Alto Medical Foundation (June 2006). Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Bretthauer, M; Hoff G, Severinsen H, Erga J, Sauar J, Huppertz-Hauss G (20 May 2004). "[Systematic quality control programme for colonoscopy in an endoscopy centre in Norway]" (in Norwegian) (Abstract). Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening 124 (10): 1402–1405. ISSN 0029-2001. PMID 15195182.

- ↑ The article PMID 20514160 was cited here, but this UID appears to be incorrect.

- ↑ Rikshospitalet University Hospital (April 2006). "Clinical Trial: Nitrous Oxide for Analgesia During Colonoscopy". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Forbes, GM; Collins BJ (March 2000). "Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy: a randomized controlled study". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 51 (3): 271–277. doi:. PMID 10699770.

- ↑ Clarke, Anthony C; Louise Chiragakis, Lybus C Hillman and Graham L Kaye (18 February 2002). "Sedation for endoscopy: the safe use of propofol by general practitioner sedationists". Medical Journal of Australia 176 (4): 158–161. PMID 11913915. http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/176_04_180202/cla10751.html. Retrieved on 2007-06-12.

- ↑ Lichtenstein, Gary R.; Peter D. Park, William B. Long, Gregory G. Ginsberg, Michael L. Kochman (18 August 1998). "Use of a Push Enteroscope Improves Ability to Perform Total Colonoscopy in Previously Unsuccessful Attempts at Colonoscopy in Adult Patients". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 94 (1): 187. doi:. PMID 9934753. Note:Single use PDF copy provided free by Blackwell Publishing for purposes of Wikipedia content enrichment.

- ↑ Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, et al. (2006). Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. 355. pp. 2533–41.

- ↑ "Colonoscopy Risks". About.com (January 16, 2008). Retrieved on 2008-07-18.

- ↑ J. A. Dominitz, et al., American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, "Complications of Colonsocopy", Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Vol 57, No. 4, 2003, pp. 441-445

- ↑ Lien YH (September 2008). "Is bowel preparation before colonoscopy a risky business for the kidney?". Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. doi:. PMID 18797448. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncpneph0939.

See also

- Anal probe

- Bow and arrow sign

- Rectal examination

- Sigmoidoscopy

- Polypectomy

- Virtual colonoscopy

External links

- Colonoscopy. Based on public-domain NIH Publication No. 02-4331, dated February 2002.

- Patient Education Brochures. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy information

|

|||||||||||