Codeine

|

|

|

|

|

Codeine

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

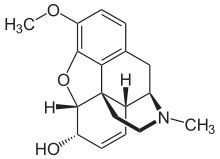

| (5α,6α)-7,8-didehydro-4,5-epoxy- 3-methoxy-17-methylmorphinan-6-ol |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | R05 N02 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C18H21NO3 |

| Mol. mass | 299.364 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~90% Oral |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, via CYP2D6 (Cytochrome P450 2D6)[1] |

| Half life | 2.5–3 hours |

| Excretion | ? |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. |

? |

| Legal status |

Controlled (S8)(AU) Schedule I(CA) Class B(UK) Schedule II(US) |

| Routes | oral, intra-rectally, SC, IM |

Codeine (INN) or methylmorphine is an opiate used for its analgesic, antitussive and antidiarrheal properties. It is by far the most widely used opiate in the world and very likely most commonly used drug overall according to numerous reports over the years by organizations such as the World Health Organization and its League of Nations predecessor agency and others. It is one of the most effective orally-administered opioid analgesics and has a wide safety margin. It is from 8 to 12 percent of the strength of morphine in most people; differences in metabolism can change this figure as can other medications.

Contents |

History

Codeine is an alkaloid found in opium and other poppy saps like Papaver bracteatum, the Iranian poppy, in concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 3.0 percent. While codeine can be extracted from opium, most codeine is synthesized from morphine through the process of O-methylation. It was first isolated in 1830 in France by Jean-Pierre Robiquet. The effects of the Nixon War On Drugs by 1972 or so had caused across-the-board shortages of illicit and licit opiates because of a scarcity of natural opium, poppy straw and other sources of opium alkaloids, and the geopolitical situation was getting less helpful for the United States. After a large percentage of the opium and morphine in the US National Stockpile of Strategic & Critical Materials had to be tapped in order to ease severe shortages of medicinal opiates -- the codeine-based antitussives in particular -- in late 1973, researchers were tasked with and quickly succeeded in finding a way to synthesize codeine and its derivatives and precursors from scratch from petroleum or coal tar using a process developed at the United States' National Institutes of Health. Numerous codeine salts have been prepared since the drug was discovered. The most commonly used are the hydrochloride (freebase conversion ratio 0.805), phosphate (0.736), sulphate (0.859) and citrate (0.842). Others include a salicylate NSAID, codeine salicylate (0.686), and at least four codeine-based barbiturates, the cyclohexenylethylbarbiturate (0.559), cyclopentenylallylbarbiturate (0.561), diallylbarbiturate (0.561), and diethylbarbiturate (0.619).

Pharmacology

Codeine is considered a prodrug, since it is metabolised in vivo to the primary active compounds morphine and codeine-6-glucuronide.[2][3] Roughly 5-10% of codeine will be converted to morphine, with the remainder either free, conjugated to form codeine-6-glucuronide (~70%), or converted to norcodeine (~10%) and hydromorphone (~1%). It is less potent than morphine and has a correspondingly lower dependence-liability than morphine.[4] Like all opioids, continued use of codeine induces physical dependence and can be psychologically addictive. However, the withdrawal symptoms are relatively mild and as a consequence codeine is considerably less addictive than the other opiates.

A dose of approximately 200 mg (oral) of codeine must be administered to give analgesia approximately equivalent to 30 mg (oral) of morphine (Rossi, 2004). However, codeine is generally not used in single doses of greater than 60 mg (and no more than 240 mg in 24 hours)[5]. When analgesia beyond this is required, stronger opioids such as hydrocodone or oxycodone are favored. Because codeine needs to be metabolized to an active form, there is a ceiling effect around 400-450 mg. This low ceiling further contributes to codeine being less addictive than the other opiates. The ceiling dose can be more accurately calculated by using 7mg per 1kg of bodyweight, taking into consideration the BMI to not over or under calculate in cases of obese or underweight people (this rule does not take into consideration the usage of other CYP2D6 inhibiting drugs, alcohol or naturally low or high enzyme presence).

Pharmacokinetics

The conversion of codeine to morphine occurs in the liver and is catalysed by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6. CYP3A4 produces norcodeine and UGT2B7 conjugates codeine, norcodeine and morphine to the corresponding 3- and 6- glucuronides. Approximately 6–10% of the Caucasian population, 2% of Asians, and 1% of Arabs[6] are "poor metabolizers"; they have little CYP2D6 and codeine is less effective for analgesia in these patients (Rossi, 2004), although it is speculated that codeine-6-glucuronide is responsible for a large percentage of the analgesia of codeine and thus these patients should experience some analgesia.[7] Many of the adverse effects will still be experienced in poor metabolizers. Conversely, 0.5-2% of the population are "extensive metabolizers"; multiple copies of the gene for 2D6 produce high levels of CYP2D6 and will metabolize drugs through that pathway more quickly than others.

Some medications are CYP2D6 inhibitors and reduce or even completely block the conversion of codeine to morphine. The most well-known of these are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, citalopram (Celexa) and especially fluoxetine (Prozac). Other drugs, such as rifampicin and dexamethasone, induce CYP450 isozymes and thus increase the conversion rate.

While a CYP2D6 extensive metaboliser (EM) needs higher doses of drugs metabolized by CYP2D6 to maintain sufficient plasma levels for therapeutic effect and a poor metaboliser (PM) may suffer from drug toxicity due to slow drug clearance and excessive plasma concentration, prodrugs like codeine have the opposite effect. Thus an EM may have adverse effects from a rapid buildup of codeine metabolites while a PM may get little or no pain relief.

The active metabolites of codeine, notably morphine, exert their effects by binding to and activating the μ-opioid receptor.

Indications

Approved indications for codeine include:

- Cough, though its efficacy in low dose over the counter formulations has been disputed.[8]

- Diarrhea

- Mild to severe pain

- Irritable bowel syndrome

Codeine is sometimes marketed in combination preparations with the analgesic, acetaminophen (paracetamol), as co-codamol, paracod, panadeine, or Tylenol 3, with the analgesic, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), as co-codaprin or with the NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug), ibuprofen, as Nurofen Plus. These combinations provide greater pain relief than either agent alone (drug synergy). Codeine is also commonly compounded with other pain killers or muscle relaxers such as Fioricet with Codeine, Soma Compound/Codeine, etc. Codeine-only products can be obtained with a prescription as a time release tablet (eg. Codeine Contin(r) 100mg) and Perduretas (50 mg).

The narcotic content number in the US names of codeine tablets and combination products like Tylenol With Codeine No. 3, Emprin With Codeine No. 4 are as follows: No. 1 - 7½ or 8 mg (1/8 grain), No. 2 - 15 or 16 mg (1/4 grain), No. 3 - 30 or 32 mg (1/2 grain), No. 4 - 60 or 64 mg (1 grain). The Canadian 222 series is identical to the above list 222=1/8 grain, 292=1/4 grain, 293=1/2 grain, and 294=1 grain of codeine.

Injectable codeine is available for subcutaneous or intramuscular injection; intravenous injection can cause a serious reaction which can progress to anaphylaxis. Codeine suppositories are also marketed in some countries.

Availability

Codeine phosphate and sulphate are marketed in the United States and Canada. Codeine hydrochloride is more commonly marketed in continental Europe and other regions, and codeine hydroiodide and codeine citrate round out the top five most-used codeine salts worldwide. Codeine is usually present in raw opium as free alkaloid in addition to codeine meconate, codeine pectinate, and possibly other naturally-occurring codeine salts. Codeine bitartrate, tartrate, nitrate, picrate, acetate, hydrobromide and others are occasionally encountered on the pharmaceutical market and in research.

In certain jurisdictions, codeine is available over-the-counter in combination with guaifenesin or promethazine to be sold at the pharmacist's discretion, though many pharmacists decline to do so.

Relation to other opiates

Codeine is the starting material and prototype of a large class of mainly mild to moderately strong opioids such as hydrocodone, dihydrocodeine and its derivatives such as nicocodeine. Related to codeine in other ways are Codeine-N-Oxide (Genocodeine), related to the nitrogen morphine derivatives as is codeine methobromide, and heterocodeine which is a drug six times stronger than morphine and 72 times stronger than codeine due to a small re-arrangement of the molecule, viz. moving the methyl group from the 3 to the 6 position on the morphine carbon skeleton. Drugs bearing resemblance to codeine in effects due to close structural relationship are variations on the methyl groups at the 3 position including ethylmorphine a.k.a. codethyline (Dionine) and benzylmorphine (Peronine). While having no narcotic effects of its own, the important opioid precursor thebaine differs from codeine only slightly in structure. Pseudocodeine and some other similar alkaloids not currently used in medicine are found in trace amounts in opium as well.

Adverse effects

Common adverse drug reactions associated with the use of codeine include euphoria, itching, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, dry mouth, miosis, orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention and constipation.[9]

Tolerance to many of the effects of codeine develops with prolonged use, including therapeutic effects. The rate at which this occurs develops at different rates for different effects, with tolerance to the constipation-inducing effects developing particularly slowly for instance.

A potentially serious adverse drug reaction, as with other opioids, is respiratory depression. This depression is dose-related and is the mechanism for the potentially fatal consequences of overdose.

As codeine is metabolized to morphine, morphine can be passed through breast milk in potentially lethal amounts, fatally depressing the respiration of a breastfed baby.[10]

Another side effect commonly noticed is the lack of sexual drive and increased complications in erectile dysfunction.[11]

Some people may also have an allergic reaction to codeine, such as the swelling of skin and rashes.[11]

Withdrawal effects

As with other opiate based pain killers chronic use of codeine can cause a physical dependence to develop. Other effects of chronic use includes depression, constipation and sexual problems. When physical dependence has developed to codeine it means if a person stops the medication too quickly they may experience withdrawal symptoms including. craving, runny nose, yawning, sweating, restless sleep, weakness, stomach cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle spasms, chills, irritability and pain. To minimise withdrawal symptoms long term users need to gradually reduce their codeine medication under the supervision of a healthcare professional.[12]

Recreational use

Codeine can be used as a recreational drug. However, it has much less abuse potential than some other opiates or opioids, such as oxycodone and hydrocodone.

In some countries, cough syrups and tablets containing codeine are available without prescription; some potential recreational users are reported to buy codeine from multiple pharmacies so as not to arouse suspicion. A heroin addict may use codeine to ward off the effects of a withdrawal.[13]

Codeine is also available in conjunction with the anti-nausea medication promethazine in the form of a syrup. Brand named as Phenergan with Codeine or generically as promethazine with codeine this medication is quickly becoming one of the most highly abused codeine preparations.[14]

Codeine is also demethylated by reaction with pyridine to illicitly synthesize morphine. Pyridine is toxic and carcinogenic, so morphine illicitly produced in this manner (and potentially contaminated with pyridine) may be particularly harmful.[15]

Controlled substance

In Australia, New Zealand, The United Kingdom, Romania, Canada and many other countries, codeine is regulated. In some countries it is available without prescription in combination preparations from licensed pharmacists in doses up to 15 mg/tablet in Australia, New Zealand and Costa Rica, 12.8 mg/tablet in the United Kingdom, 8 mg/tablet in Canada and 10mg/tablet in Israel.

Canada

In Canada, codeine can be sold over the counter only in combination with two or more ingredients, which has resulted in the prevalence of AC&C (aspirin, codeine, and caffeine), and similar combinations using acetaminophen (paracetamol) rather than aspirin. Caffeine, being a stimulant, tends to offset the sedative effects of codeine. It also can increase the effectiveness and absorption rate of analgesics in some circumstances.[16]

Germany, Switzerland & Austria

Codeine is listed under the Betäubungsmittelgesetz in Germany and the similarly-named narcotics & controlled substances law in Switzerland. In Austria, the drug is listed under the Suchtmittelgesetz in categories corresponding to their classification under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Dispensing of products containing codeine and similar drugs (dihydrocodeine, nicocodeine, benzylmorphine, ethylmorphine &c.) generally require a prescription order from a doctor or the discretion of the pharmacist. Municipal and provincial regulations may impact the range of products which can be dispensed in the latter case.

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, codeine is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It can be used legally only by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without prescription can be fined $10,000(HKD). The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing the substance is a $5,000,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 (HKD) fine and/or 7 years of jail time.

However, codeine is available without prescription from licensed pharmacists in doses up to 0.1% (5mg/5ml) according to Hong Kong "Dangerous Drugs Ordinance".

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, codeine formulations are prescription only medicines, with the exception of (various brand) co-codamol tablets(8/500) or Panadol Ultra(12.8/500) where 8 or 12.8mg of codeine phosphate is combined with 500mg paracetamol which are available as a pharmacy supervised medicine (behind the counter). This also applies to medicines containing Ibuprofen, which can contain 12.8mg Codeine alongside 200mg Ibuprofen per tablet. Intramuscular injection of codeine is a controlled drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

United States

In the United States, codeine is regulated by the Controlled Substances Act. It is a Schedule II controlled substance for pain-relief products containing codeine alone or more than 90 mg per dosage unit. In combination with aspirin or acetaminophen (paracetamol/Tylenol) it is listed as Schedule III or V, depending on formula. Preparations for cough or diarrhea containing small amounts of codeine in combination with two or more other active ingredients are Schedule V in the US, and in some states may be dispensed in amounts up to 4 fl. oz. per 48 hours without a prescription. Schedule V specifically consigns the product to state and local regulation beyond certain required record-keeping requirements (a dispensary log must be maintained for two years in a ledger from which pages cannot easily be removed and/or are pre-numbered and the pharmacist must ask for a picture ID such as a driving licence) and also which maintain controlled substances in the closed system at the root of the régime intended by the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 -- e.g. the codeine in these products was a Schedule II substance when the company making the Schedule V product acquired it for mixing up the end product. In locales where dilute codeine preparations are non-prescription, anywhere from very few to perhaps a moderate percentage of pharmacists will sell these preparations without a prescription. However, many states have their own laws that do require a prescription for Schedule V drugs. Other drugs which are present in Schedule V narcotic preparations like the codeine syrups are ethylmorphine and dihydrocodeine. Paregoric and hydrocodone were transferred to Schedule III from Schedule V even if the preparation contains two or more other active ingredients, and diphenoxylate is usually covered by state prescription laws even though this relative of pethidine is a Schedule V substance when adulterated with atropine to prevent abuse.

Codeine is also available outside the United States as an over-the-counter drug in liquid cough-relief formulations. Internationally, codeine is, contingent on its concentration, a Schedule II and IV drug under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[17]

Other Countries

Most national controlled-substance laws are implementations of requirements in the Single Convention and related treaties. The aforementioned dilute preparations are scheduled in such a way that in many countries preparations, liquid or solid, of codeine, dihydrocdeine, nicocodeine, nicodicodeine, benzylmorphine, propoxyphene, dextropropoxyphene, and acetyldihydrocodeine may be non-prescription and/or over the counter; some local, provincial and national regulations and registry programmes in various European and Pacific Rim countries may provide for even stronger analgesic preparations of the aforementioned drugs to be dispensed by the senior chemist without prescription or after an initial prescription with certain volume, documentation, and record-keeping requirements.

References

- ↑ Drug Metab Dispos. 2007 Aug;35(8):1292-300

- ↑ Vree TB, van Dongen RT, Koopman-Kimenai PM (2000). "Codeine analgesia is due to codeine-6-glucuronide, not morphine". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 54 (6): 395–8. PMID 11092114.

- ↑ Srinivasan V, Wielbo D, Tebbett IR (1997). "Analgesic effects of codeine-6-glucuronide after intravenous administration". European journal of pain (London, England) 1 (3): 185–90. PMID 15102399.

- ↑ Vree TB, van Dongen RT, Koopman-Kimenai PM (2000). "Codeine analgesia is due to codeine-6-glucuronide, not morphine". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 54 (6): 395–8. PMID 11092114.

- ↑ http://www.sdrl.com/druglist/codeine.html retrieved December 1, 2008

- ↑ "Codeine Information - Facts - Codeine". Retrieved on 2007-07-16.

- ↑ Srinivasan V, Wielbo D, Tebbett IR (1997). "Analgesic effects of codeine-6-glucuronide after intravenous administration". European journal of pain (London, England) 1 (3): 185–90. PMID 15102399.

- ↑ Schroeder K, Fahey T (2001). "Over-the-counter medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings". Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD001831. doi:. PMID 15495019.

- ↑ Australian Medicines Handbook (2004). Rossi S. ed.. Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0975791923. OCLC 224831213 224913182.

- ↑ CTV News, Codeine use while breastfeeding may be dangerous, Wed. Aug. 20 2008 9:42 PM ET

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Codeine Information from Drugs.com

- ↑ Alberta Health Services; AADAC (April 16, 2007). "The ABCs - Codeine and Other Opioid Painkillers". Alberta Alcohol and Drug Abuse Commission. Retrieved on Sep 12, 2008.

- ↑ Boekhout van Solinge, Tim. "7. La politique de soins des années quatre-vingt-dix" (in French). L'héroïne, la cocaïne et le crack en France. Trafic, usage et politique. Amsterdam: CEDRO Centrum voor Drugsonderzoek, Universiteit van Amsterdam. pp. 247–262.

- ↑ Leinwand, Donna (2006-10-18). "DEA warns of soft drink-cough syrup mix", USA Today. Retrieved on 2006-10-23.

- ↑ Hogshire, Jim (June 1999). Pills-A-Go-Go: A Fiendish Investigation into Pill Marketing, Art, History & Consumption. Los Angeles: Feral House. pp. 216–223. ISBN 0922915539.

- ↑ "Headache Triggers: Caffeine". WebMD (June 2004). Retrieved on 2007-03-23.

- ↑ International Narcotics Control Board. "List of Narcotic Drugs under International Control" (PDF). Retrieved on 2006-05-24.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||