Coccinellidae

| Coccinellidae | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coccinella septempunctata

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Subfamilies | ||||||||||||

|

Chilocorinae |

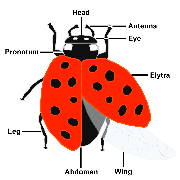

Coccinellidae is a family of beetles, known variously as ladybirds (British English, Australian English, South African English), ladybugs (North American English) or lady beetles (preferred by some scientists). Lesser-used names include ladyclock, lady cow, and lady fly.[1] The family name comes from its type genus, Coccinella. Coccinellids are found worldwide, with over 5,000 species described,[2] more than 450 native to North America alone. Coccinellids are small insects, ranging from 1 mm to 10 mm (0.04 to 0.4 inches), and are commonly yellow, orange, or scarlet with small black spots on their wing covers, with black legs, head and antennae. A very large number of species are mostly or entirely black, gray, or brown and may be difficult for non-entomologists to recognize as coccinellids (and, conversely, there are many small beetles that are easily mistaken as such, like tortoise beetles).

Coccinellids are generally considered useful insects as many species feed on aphids or scale insects, which are pests in gardens, agricultural fields, orchards, and similar places. The Mall of America, for instance, releases thousands of ladybugs into its indoor park as a natural means of pest control for its gardens.[3] Some people consider seeing them or having them land on one's body to be a sign of good luck to come, and that killing them presages bad luck. A few species are pests in North America and Europe.

Contents |

Biology

Coccinellids are typically predators of Hemiptera such as aphids and scale insects, though members of the subfamily Epilachninae are herbivores, and can be very destructive agricultural pests (e.g., the Mexican bean beetle), though conspecific larvae and eggs are also important resources, particularly when alternative prey are scarce. While they are often used as biological control agents, introduced species of ladybirds (such as Harmonia axyridis or Coccinella septempunctata in North America) outcompete and displace native coccinellids, and become pests in their own right.

Coccinellids are often brightly colored to ward away potential predators. This phenomenon is called aposematism and works because predators learn by experience to associate certain prey phenotypes with a bad taste (or worse). Mechanical stimulation (such as by predator attack) causes "reflex bleeding" in both larval and adult ladybird beetles, in which an alkaloid toxin is exuded through the joints of the exoskeleton, deterring feeding.

Most coccinellids overwinter as adults, aggregating on the south sides of large objects such as trees or houses during the winter months, and dispersing in response to increasing day length in the spring.[4] In Harmonia axyridis, eggs hatch in 3–4 days from clutches numbering from a few to several dozen. Depending on resource availability, the larvae pass through four instars over 10–14 days, after which pupation occurs. After a teneral period of several days, the adults become reproductively active and are able to reproduce again, although they may become reproductively quiescent if eclosing late in the season.

It is thought that certain species of Coccinellids lay extra infertile eggs with the fertile eggs. These appear to provide a backup food source for the larvae when they hatch. The ratio of infertile to fertile eggs increases with scarcity of food at the time of egg laying.[5]

Habitats

Most coccinellids are beneficial to gardeners in general, as they feed on aphids, scale insects, mealybugs, and mites throughout the year. As in many insects, ladybirds in temperate regions enter diapause during the winter, so they often are among the first insects to appear in the spring. Some species (e.g., Hippodamia convergens) gather into groups and move to higher land, such as a mountain, to enter diapause. Predatory ladybirds are usually found on plants where aphids or scale insects are, and they lay their eggs near their prey, to increase the likelihood the larvae will find the prey easily. Ladybirds are cosmopolitan in distribution, as are their prey.

Coccinellids as household pests

Although native species of coccinellids are typically considered benign, in North America the multicolored Asian lady beetle (Harmonia axyridis), introduced in the twentieth century to control aphids on agricultural crops, has become a serious household pest in some regions owing to its habit of overwintering in structures. It is similarly acquiring a pest reputation in Europe, where it is called the "Multicoloured Asian Ladybird" (In Britain: "Harlequin Ladybird") (see main article Harmonia axyridis for discussion).

Coccinellids in popular culture

Coccinellids are and have for very many years been favourite insects of children. The insects had many regional names (now mostly disused) such as the lady-cow, may-bug, golden-knop, golden-bugs (Suffolk); and variations on Bishop-Barnaby (Norfolk dialect) – (Barney, Burney) Barnabee, Burnabee, and the Bishop-that-burneth.

The ladybird is immortalised in the still-popular children's nursery rhyme Ladybird, Ladybird:

Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home

Your house is on fire and your children are gone

All except one, and that's Little Anne

For she has crept under the warming pan.

In parts of Northern Europe, tradition says that one's wish granted if a ladybird lands on oneself (this tradition lives on in North America, where children capture a ladybird, make a wish, and then "blow it away" back home to make the wish come true). In Italy, it is said by some that if a ladybird flies into one's bedroom, it is considered good luck. In central Europe, a ladybird crawling across a girl's hand is thought to mean she will get married within the year. In some cultures they are referred to as lucky bugs (Turkish: uğur böceği).

In Russia, a popular children's rhyme exists with a call to fly to the sky and bring back bread; similarly, in Denmark a ladybird, called a mariehøne ("Mary's hen"), is asked by children to fly to 'our lord in heaven and ask for fairer weather in the morning'.

The name that the insect bears in the various languages of Europe is mythic. In this, as in other cases, the Virgin Mary has supplanted Freyja, the fertility goddess of Norse mythology; so that Freyjuhaena and Frouehenge have been changed into Marienvoglein, which corresponds with Our Lady's Bird. The esteem with which these insects are regarded has roots in ancient beliefs.[6]

In Irish, the insect is called bóín Dé — or "God's little cow"; similarly, in Croatian it is called Božja ovčica ("God's little sheep"). In France it is known as bête à bon Dieu, "the Good Lord's animal",[7] and in Russia, Божья коровка ("God's little cow"),[7] while in both Hebrew and Yiddish, it is called "Moshe Rabbenu's (i.e. Moses's) little cow" or "Moshe Rabbenu's little horse", apparently an adaptation of the Russian name, or sometimes "Little Messiah".[7]

In Greece, ladybirds are called πασχαλίτσα (paschalitsa), because they are found abundantly in Eastertime, along with paschalia, the Common Lilac plant, which flowers at the same time.

In Malta, the ladybird is called nannakola, and little children sang: Nannakola, mur l-iskola/Aqbad siġġu u ibda ogħla (Ladybird go to school, get a chair and start jumping).

In Finnish, ladybird is called leppäkerttu, translating to blood-Gertrud, which refers to the red color. An alternative name is leppäpirkko. These differ by the female name at the end (Pirkko refers to Bridget).

As a logo

- The ladybird is the symbol of the Dutch Foundation Against Senseless Violence, as can be seen in the logo.

- Other companies using ladybirds as their corporate logo include: Ladybird Books (owned by Pearson PLC); the Ladybird range of children's clothing sold by Woolworth's in the UK; the Polish supermarket chain Biedronka; the Estonian mobile operator EMT; and the software development firm Axosoft.

- The ladybird is a symbol of the Finnish Swedish People's Party.

- Many states in the U.S. have chosen a ladybird species as their state insect; Delaware, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee.

In music

- The British band XTC included a song called "Ladybird," an affectionate ode to the insect, on their 1983 album Mummer.

- The British band The Fall included a song called "Ladybird (Green Grass)," on their 1993 album The Infotainment Scan.

- The Alternative metal band Breaking Benjamin has a song titled "Lady Bug" on the So Cold EP.

- The Finnish fusion rock band 22-Pistepirkko has got its name from the Finnish name for the 22-spot ladybird.

Other

- The Bad-Tempered Ladybird is a book by Eric Carle.

- Ladybugs is a 1992 movie starring Rodney Dangerfield.

- A ladybird appears in each of artists Michael Quinlyn-Nixon's illustrations.

- In the mid 1980's, presenter and TV producer Muriel Young, made two series of programmes entitled 'Ladybirds', a Channel 4 programme from Mike Mansfield's independent company, in which she interviewed female singers, including Barbara Dickson, Elaine Paige and Kiki Dee, as well as American and French stars Rita Coolidge and Jane Birkin.

Gallery

References

- ↑ Definition of lady cow, Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary (1913), provided by die.net, accessed 14 November 2008

- ↑ Judy Allen & Tudor Humphries (2000). Are You A Ladybug?, Kingfisher, p. 30

- ↑ Matthew Power, "Top Tech City: Minneapolis, MN", PopSci.com (http://www.popsci.com/scitech/article/2005-03/top-tech-city-minneapolis-mn?page=4), accessed April 19 2008

- ↑ A. Honek, Z. Martinkova & S. Pekar (2007). "Aggregation characteristics of three species of Coccinellidae (Coleoptera) at hibernation sites". European Journal of Entomology 104 (1): 51–56. http://www.eje.cz/pdfarticles/1197/eje_104_1_051_Honek.pdf.

- ↑ J. Perry & B. Roitberg (2005). "Ladybird mothers mitigate offspring starvation risk by laying trophic eggs". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 58: 578–586. doi:.

- ↑ "Bishop Barnaby". Notes and Queries 9. 1849-12-29. http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/13521.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Born to Kvetch, Michael Wex, St. Martin's Press, New York, 2005, ISBN 0-312-30741-1

External links

- BBC Science & Nature: 7-spotted ladybird

- Ladybugs of North America — diagnostic photographs

- Multicolored Asian ladybug Harmonia axyridis male and female specimens photos

- Ladybirds page on The Earth Life Web

- Lady beetles on eNature

- Harlequin Ladybird survey in the British Isles

- Unofficial Homepage to the Asian ladybird beetle

- General Information on Ladybugs (Asian LadyBeetle)

- Biological control: Predators: Lady beetles Cornell University's Guide to natural enemies in North America

- Taxonomy of coccinellids

- lady beetles of Florida on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site