Classical guitar

|

|

| Classification | String instrument (plucked) |

|---|---|

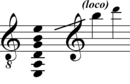

| Playing range | |

|

|

| Related instruments | *Guitar family (Steel-string acoustic guitar, Electric guitar, Flamenco guitar, Bass guitar)

|

| Musicians | *List of classical guitarists |

The classical guitar, also known as the "Spanish guitar", "gut string guitar", "flamenco guitar", "spruce top", "flat top" and "nylon string guitar" — is a musical instrument from the family of instruments called chordophones.

The classical guitar is characterised by:

- its shape — modern guitar shape, or historic guitar shapes[1]

- its strings — traditionally made of gut, but today primarily nylon; the bass-strings additionally being wound with a thin metal thread

- the instrumental technique — the individual strings are usually plucked with the fingers or the fingernails, as opposed to using a plectrum or pick

- its historic repertoire, though this is of lesser importance, since any repertoire can be and is played on the guitar.

The name classical guitar does not mean that only classical repertoire is performed on it, although classical music is a part of the instrument's core repertoire; instead all kinds of music (classical, flamenco, jazz, etc.) can be and are performed on it.

The classical guitar as an instrument has a long history that has seen it evolve through multiple forms, and while its modern form (modern classical guitar) is what is primarily available today, many luthiers today also build guitars with historic shapes (e.g. replicas of romantic guitars, ...): A Guitar Family Tree can be identified, which includes guitars from different periods, with different shapes and construction-features, as well as different string configurations (double-strung courses or single strings, different tunings, different numbers of strings).

Background information

The evolution of the classical guitar and its repertoire spans more than four centuries. It has a history that was shaped by contributions from earlier instruments, such as the Renaissance guitar, vihuela, and the baroque guitar. The popularity of the classical guitar has been sustained over the years by many great players, arrangers, and composers. A very short list might include, Gaspar Sanz (1640-1710), Fernando Sor (1778-1839), Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829), Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909), Agustín Barrios Mangoré (1888-1944), Andrés Segovia (1893-1987), Alirio Diaz (1923), Presti-Lagoya Duo (active from 1955-1967: Ida Presti, Alexandre Lagoya), Julian Bream (1933), and John Williams (1941).

Performance

The right and left hand descriptions in this section are typical for right-handed guitarists.

Plucking of the string

Right-handed players usually use the fingers of the right hand to pluck the strings (with the thumb plucking from the top of a string downward, and the other fingers plucking from the bottom of string upward). The little finger is seldom used because of its small size. (Some guitarists such as Štěpán Rak compensate this with an extremely long fingernail on the little finger.)

Changing a string's active vibrating length (frets)

The fingers of the other hand are usually used to change the vibrating length of a string: the finger pushes the string towards a fret to achieve this. The shorter the string, the higher its pitch.

Direct contact with strings

As with other plucked instruments (such as the lute), the musician directly touches the strings (usually plucking) to produce the sound. This has important consequences: Different tone/timbre (of a single note) can be produced by plucking the string in different manners and in different positions.

Tone production/variation and freedom of performance

Guitarists have a lot of freedom within the mechanics of playing the instrument. Often these decisions influence the tone/timbre - factors include:

Right Hand (also known as pick hand):

- At what position along the string the finger plucks the string (This is actively changed by guitarists since it is an effective way of changing the sound(timbre) from "soft"(dolce) plucking the string near its middle, to "hard"(ponticelo) plucking the string near its end)

- Use of nail or not: today almost all concert guitarists use their fingernails (which have to be smoothly and roundly filed) to pluck the string since it produces a sharper clearer sound, and also a better controlled loud sound is possible . When using the nail (of index, middle, ring or little finger) to pluck the string, the hand is usually held so that the left side of the nail makes the first contact with the string: this is not achieved by "rolling" the hand to the left, but rather by holding the hand in such a way, that the outstretched fingers are angled slightly the left relative to the strings (as opposed to perpendicular). Before plucking, usually both the left side of the nail and the fingertip touch the string; this enables the finger (and hand) to rest on the string in a balanced way. When the plucking motion is made, only the nail-contact remains: The curvature of the nail (starting from its left side) allows the string to be pulled back while the string slides towards the tip of the nail where it is released. This occurs so quickly that the gliding of the string over the fingernail is not perceived (but: a smoothly filed nail is necessary).

The "use of nail or not" is usually a fixed consistent decision of the player and not varied; the thumb is an exception and might actively be varied between using nail [sharper clearer sound] and using flesh. - Which finger to use (the thumb may be able to produce a different tone than the other fingers)

- At what angle the wrist and fingers are held with respect to the strings (angle of attack), for plucking. This is varied by guitarists (however only minimally) and effects the produced tone. Modern guitarists (often use a fair amount of nail and thus) seldom hold their hand (such that the outstretched fingers are) at right angles to the strings (this produces excessive clicking noises), but use a more natural angled hand position (with variations), which produces a better tone. Often a tradeoff is involved: Some rich sounds that are achieved by having the finger rather parallel (if it were outstretched) to the string, do not easily allow fast plucking.

- Rest-stroke (apoyando; having the finger that plucks a string come to a rest on the next string - traditionally used in single melody lines) versus free-stroke (tirando; plucking the string without coming to a rest on the next string): Usually influenced by the nails. Some guitarists with rather long nails avoid the rest-stroke altogether; others avoid it when they feel they have more control over the free-stroke. When two neighboring strings are to be plucked simultaneously, the rest-stroke cannot be used.

Left Hand:

- Use of hammer-on and pull-off (Legato, slurs): This is where only the left hand is used in producing the sound - during hammer-on, the finger hits the already vibrating string down towards a fret, thus shortening the vibrating string and increasing the pitch. During pull-off, a finger that holds the string lengthened to a particular fret, is pulled off, resulting in a lengthening of the string either to its open length or to another finger-fret position, thus decreasing the pitch. Since the string is usually already vibrating prior to applying the hammer-on or pull-off, the change of pitch is very smooth: it is hence used for articulation purposes and fast note progressions (since only a single hand is involved). The technique is often used in trills, where e.g. the first finger remains pivoted at a lower fret and the 2nd finger might hammer-on and pull-off repeatedly resulting in the trill.

- Vibrato: Whilst a finger of the left-hand is pressing the string towards a fret, it can rapidly move to string slightly to and fro (along the string), resulting in a slight but fast-changing increase and decrease in the string's tension and thus a proportional change in pitch - giving the impression of a fuller tone.

Both Hands/Other:

- One and the same note (in terms of pitch), can be played on many different strings (depending on the appropriate fret being used). Since the different strings have distinctive tones, the guitarist may choose to play on certain strings for particular tonal effects: The difference is greatest between the 3rd string (G - pure nylon) and the 4th string (D - nylon wound with thin metal). However at the same time this is also a great difficulty when a melody line (which should have a uniform sound) is played across the strings; since the guitarist has to adjust so as to emphasize tonal similarity, rather than difference. Another example for the use of strings is tone production is the cross-string trill, where the different pitches of the trill are plucked on neighboring strings[2][3]: this can be used to create a rather dissonant trill (but with the benefit of better volume), since both strings may be allowed to sound simultaneously if the guitarist so chooses.

- Harmonics: The strings can be brought into different modes of vibration, where its overtones can be heard. This is achieved by laying a left-hand finger lightly at a position of an integer division of the string's length (1/2, 1/3, 2/3, etc.) and plucking the string with the other hand (followed by removing the left-hand finger). This causes separate string-parts to vibrate separately, with a "standing, motionless" point where the left-hand finger originally touched the string.

Since it is the hands and fingers that pluck the string and every person has different fingers, there are great differences in playing between guitarists; who often spend a lot of time finding their own way of playing that suits them best in terms of specific objectives: tone-production ("beauty"/quality of tone), minimum noise (e.g. clicking), large dynamic range (from soft to controlled loud), minimum (muscle) effort, fast "motion-recovery" (fast plucking when desired), healthy movement in fingers, wrist, hand and arm

There is not one definite way of reaching these goals (there is not a single definite optimal guitar technique): rather there are different ways of reaching these goals, due to differences in the hands and fingers (including nails) of guitarists.

When guitarists are performing music (while playing), they continually search (by actively moving/changing their hands, fingers) for a good sound in terms of tone/timbre, to enhance the musical interpretation.

John Williams has remarked[4] that since guitarists find it superficially very easy to play even things such as melody with accompaniment (e.g. Giuliani), [some guitarists'] "approach to tone production is also superficial, with little or no consideration given to voice matching and tonal contrasts".

See also Classical guitar technique.

Pedagogy (Teaching, Learning)

Aspects of phrasing, rubato, musical communication:

History

The history of the classical guitar and its repertoire span over four centuries. Included in its ancestry is the baroque guitar. Throughout the centuries, the classical guitar has evolved principally from three sources: the lute, the vihuela, and the Renaissance five-string guitar.

Origins

Instruments similar to what we know as the guitar have been popular for at least 5,000 years. The ancestry of the modern guitar appears to trace back through many instruments and thousands of years to ancient central Asia. Guitar like instruments appear in ancient carvings and statues recovered from the old Iranian capital of Susa. This means that the contemporary Iranian instruments such as the tanbor and setar are distantly related to the European guitar, as they all derive ultimately from the same ancient origins, but by very different historical routes and influences.

Overview of the classical guitar's history

During the Middle Ages, guitars with three, four, and five strings were already in use. The Guitarra Latina had curved sides and is thought to have come to Spain from elsewhere in Europe. The so-called Guitarra Morisca, brought to Spain by the Moors, had an oval soundbox and many sound holes on its soundboard. By the 15th century, a four course double-string guitar called the vihuela de mano, half way between the lute and the modern guitar, appeared and became popular in Spain and spread to Italy; and by the sixteenth century, a fifth double-string had been added and some even had a sixth string. During this time, composers wrote mostly in tablature notation. In the 17th century, influences from the vihuela and Renaissance five string guitar were combined in the baroque guitar. The baroque quickly superseded the vihuela in popularity and Italy became the center of the guitar world. Leadership in guitar developments switched back to Spain from the late 18th century, when the six string guitar quickly became popular at the expense of the five string guitars. During the 19th century, improved communication and transportation enabled performers to travel widely and the guitar gained greater popularity outside its old strongholds in Iberia, Italy and Latin America. During the 19th century an Andalusian Spaniard, Antonio de Torres, gave the modern classical guitar its definitive form, with a broadened body, increased waist curve, thinned belly, improved internal bracing, single string courses replacing double courses, and a machined head replacing wooden tuning pegs. The modern classical guitar replaced older form for the accompaniment of song and dance called flamenco, leading to the development of the flamenco guitar.

Renaissance

The Renaissance guitar

The gittern, English for Renaissance guitar, is a musical instrument resembling a small lute or guitar. It is related to but is not a citole, another medieval instrument. The gittern was carved from a single piece of wood with a curved ("sickle-shaped") pegbox. An example has survived from around 1450.

The Vihuela

The written history of the classical guitar can be traced back to the early sixteenth century with the development of the vihuela in Spain. While the lute was then becoming popular in other parts of Europe, the Spaniards did not take to it well because of its association with the Moors . They turned instead to the four string guitarra, adding two more strings to give it more range and complexity. In its most developed form, the vihuela was a guitar-like instrument with six double strings made of gut, tuned like a modern classical guitar with the exception of the third string, which was tuned half a step lower.

Baroque guitar

A Guitar from the Baroque era.

"Early romantic guitar" or "Guitar during the Classical music era"

The earliest extant six string guitar was built in 1779 by Gaetano Vinaccia (1759 - after 1831) [5] [6] in Naples, Italy. The Vinaccia family of luthiers is known for developing the mandolin. This guitar has been examined and does not show tell-tale signs of modifications from a double-course guitar. [7] The authenticity of guitars allegedly produced before the 1790s is often in question. This also corresponds to when Moretti's 6-string method appeared, in 1792.

Contemporary classical guitar

Contemporary concert guitars occasionally follow the Smallman design which replaces the fan braces with a much lighter balsa brace attached to the back of the sound board with carbon fiber. The balsa brace has a honeycomb pattern and allows the (now much thinner) sound board to support more vibrational modes. This leads to greater volume and longer sustain.

Multi-string classical guitar

A multi-string classical guitar is a classical guitar with more than 6 strings, usually between 7 and 10.

Modern 10-string guitar

The Modern/Yepes 10-string guitar adds four strings (resonators) tuned in such a way that they (along with the other three bass strings) can resonate in unison with any of the 12 chromatic notes that can occur on the higher strings; the idea behind this being an attempt at enhancing and balancing sonority.

Repertoire

The classical guitar repertoire in practical terms includes not only music written specifically for the classical guitar, but also music written for the guitar's predecessors and related instruments. These include the vihuela, popular in sixteenth-century Spain, and the lute used everywhere else in Europe in the Renaissance and Baroque eras. Music written specifically for the classical guitar dates from the addition of the sixth string (the baroque guitar normally had five pairs of strings) in the late 18th century.

A guitar recital may include a variety of works, e.g. works written originally for the lute or vihuela by composers such as John Dowland (b. England 1563) and Luis de Narváez (b. Spain c. 1500), and also music written for the harpsichord by Domenico Scarlatti (b. Italy 1685), for the baroque lute by Sylvius Leopold Weiss (b. Germany 1687), for the baroque guitar by Robert de Visée (b. France c. 1650) or even Spanish-flavored music written for the piano by Isaac Albéniz (b. Spain 1860) and Enrique Granados (b. Spain 1867). The most important composer who did not write for the guitar but whose music is often played on guitar is Johann Sebastian Bach (b. Germany 1685) whose works for solo violin and solo cello as well as those written for baroque lute have proved to be highly adaptable for the guitar. Indeed, they have become core repertoire for guitarists.

Of the music written originally for guitar the earliest important composers are from the classical period and include Fernando Sor (b. Spain 1778) and Mauro Giuliani (b. Italy 1781) both of whom wrote in a style strongly influenced by Viennese classicism. In the nineteenth century guitar composers such as Johann Kaspar Mertz (b. Slovakia, Austria 1806) were strongly influenced by the dominance of the piano. It is not until the end of the century that the guitar began to emerge with its own unique atmosphere. Francisco Tárrega (b. Spain 1852) was central to this, sometimes incorporating some stylized aspects of flamenco, which has Moorish influences, into his romantic miniatures. This was part of the phenomenon of musical nationalism that was part of the wider European mainstream in the late nineteenth century. The aforementioned piano composers Albéniz and Granados were central to this movement and their evocation of the guitar was so successful that guitarists have largely appropriated their music for piano to the guitar. Guitarists who were active at that time, such as Angel Barrios (Spain, 1882 - 1964) contributed to the incorporation of flamenco style (e.g. the Phrygian mode) and flamenco guitar techniques such as rasgueado.

With the twentieth century and the wide-ranging performances of artists such as Andrés Segovia and Agustin Barrios-Mangore the guitar began to regain some of the popularity it had lost to the harpsichord and piano in the eighteenth century. It again became a popular instrument, but not always in its classical version. The steel-string and electric guitars, integral to the rise of rock and roll in the post-WWII era, became more widely played in North America and the English speaking world. The classical guitar also became widely popular again. Barrios composed many excellent works and brought into the mainstream the characteristics of Latin American music, as did the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos. Andrés Segovia commissioned many works from Spanish composers such as Federico Moreno Torroba and Joaquin Rodrigo, Italians such as Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Latin American composers such as Manuel M. Ponce of Mexico, Agustin Barrios-Mangore of Paraguay, Leo Brouwer of Cuba, Antonio Lauro of Venezuela, Enrrique Solares of Guatemala. Julian Bream of Great Britain managed to get nearly every British composer from William Walton to Benjamin Britten to Peter Maxwell Davies to write significant works for guitar. Bream's collaborations with tenor Peter Pears also resulted in song-cycles by Britten, Lennox Berkeley and others. There are also significant works by composers such as Hans Werner Henze of Germany. The classical guitar also became widely used in popular music and rock & roll in the 1960s after guitarist Mason Williams popularized the instrument in his instrumental hit Classical Gas. Guitarist Christopher Parkening is quoted in the book Classical Gas: The Music of Mason Williams as saying that it is the most requested guitar piece besides Malagueña and perhaps the best known instrumental guitar piece today.

Classical guitar making

Physical characteristics

The classical guitar is distinguished by a number of characteristics:

- It is an acoustic instrument. The sound of the plucked string is amplified by the soundboard of the guitar which acts as a resonator.

- It has six strings; however, a few classical guitars have eight or more strings to expand the bass range, and to expand the repertoire of the guitar.

- All six strings are made from nylon, as opposed to the metal strings found on other acoustic guitars. Nylon strings also have a much lower tension than steel strings, as do the predecessors to nylon strings, gut strings (made from ox gut). The lower three strings ('bass strings') are wound with metal, commonly silver plated copper.

- Because of the low tension of the strings the neck can be made entirely of wood, not requiring a steel truss rod.

- The interior bracing of the sound board can be lighter, due to the low tension of the strings. This can allow for more complex tonal qualities. A common classical guitar bracing pattern is the fan bracing. A center spruce brace is glued on the inside of the soundboard along the center line of the guitar to just before the bridge. Additional braces fan out on ether side of the first brace.

- A typical modern six-string classical guitar has a width of 48-54 mm at the nut, compared to around 42 mm for a modern electric guitar design. The classical fingerboard is normally flat and without inlays (Some have dot inlays on the side of the neck at the 5th and 7th frets), whereas the steel string fingerboard has a slight radius and inlays.

- Classical guitarists use their dominant hand fingers to pluck the strings. Players shape their fingernails, much the way a clarinetist will shape their reed to achieve a desired tone.

- Strumming is a less common technique in classical guitar, and is often referred to by the Spanish term "rasgueo", or for strumming patterns "rasgueado", and utilises the backs of the fingernails. Rasgueado is integral to Flamenco guitar.

- Tuning pegs (or "keys") at the head the fingerboard of a classical guitar point backwards (towards the player when the guitar is in playing position; perpendicular to the plane of the fretboard). This is in contrast to a traditional steel-string guitar design, in which the tuning pegs point outward (up and down from playing position; parallel to the plane of the fretboard).

- The overall design of a Classical Guitar is very similar to the slightly lighter and smaller Flamenco guitar.

Parts of the guitar

- 1 Headstock

- 2 Nut

- 3 Machine heads (or pegheads, tuning keys, tuning machines, tuners)

- 4 Fretwires

- 5 Truss rod (not shown)

- 7 Neck and 20 fretboard

- 8 Heel

- 9 Body

- 12 Bridge

- 14 Bottom deck

- 15 Face (top deck)

- 16 Body sides

- 17 Sound hole, with Rosette inlay

- 18 Strings

- 19 Bridge saddle (Bridge nut)

- 20 The Fretboard

Fretboard

The fretboard (also called the fingerboard) is a piece of wood embedded with metal fretwires that constitutes the top of the neck. It is flat or slightly curved. The curvature of the fretboard is measured by the fretboard radius, which is the radius of a hypothetical circle of which the fretboard's surface constitutes a segment. The smaller the fretboard radius, the more noticeably curved the fretboard is. Pinching a string against the fretboard effectively shortens the vibrating length of the string, producing a higher tone (a string, unfingered, will vibrate from the saddle to the nut; once fingered, it will vibrate only along the distance between the saddle and the fretwire directly before the finger). Fretboards are most commonly made of ebony, but may also be made of rosewood or of phenolic composite ("micarta").

Frets

Frets are the metal strips (usually nickel alloy or stainless steel) embedded along the fingerboard and placed at points that divide the length of string mathematically. The strings' vibrating length is determined when the strings are pressed down behind the frets. Each fret produces a different pitch and each pitch spaced a half-step apart on the 12 tone scale. The ratio of the widths of two consecutive frets is the twelfth root of two ![\sqrt[12]{2}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/70b8b8fc763c20423a65bd934e378085.png) , whose numeric value is about 1.059463. The twelfth fret divides the string in two exact halves and the 24th fret (if present) divides the string in half yet again. Every twelve frets represents one octave. This arrangement of frets results in equal tempered tuning. For more on fret spacing, see the Strings and Tuning section.

, whose numeric value is about 1.059463. The twelfth fret divides the string in two exact halves and the 24th fret (if present) divides the string in half yet again. Every twelve frets represents one octave. This arrangement of frets results in equal tempered tuning. For more on fret spacing, see the Strings and Tuning section.

Frets are placed at fractions of the length of a string (the string midpoint is at the 12th fret; one-third the length of the string reaches from the nut to the 7th fret, the 7th fret to the 19th, and the 19th to the saddle; one-quarter reaches from nut to fifth to twelfth to twenty-fourth to saddle). This feature is helpful when playing harmonics.

Frets are usually the first permanent part to wear out on a heavily played guitar. They can be re-shaped to a certain extent and can be replaced as needed. Frets are available in several different gauges, depending on the type of guitar and the player's requirements.

Truss rod

The truss rod is an adjustable metal rod that runs along the inside of the neck, adjusted by a hex key or an allen-wrench bolt usually located either at the headstock (under a cover) or just inside the body of the guitar, underneath the fretboard (accessible through the sound hole). Most classical guitars do not have truss rods, as the nylon strings do not put enough tension on the neck for one to be needed. The truss rod counteracts the immense amount of tension the strings place on the neck, bringing the neck back to a straighter position. The truss rod can be adjusted to compensate for changes in the neck wood due to changes in humidity or to compensate for changes in the tension of strings. Tightening the rod will curve the neck back and loosening it will return it forward. Adjusting the truss rod affects the intonation of a guitar as well as affecting the action (the height of the strings from the fingerboard). Some truss rod systems, called "double action" truss systems, will tighten both ways, allowing the neck to be pushed both forward and backward (most truss rods can only be loosened so much, beyond which the bolt will just come loose and the neck will no longer be pulled backward).

Neck

A classical guitar's frets, fretboard, tuners, headstock, and truss rod, all attached to a long wooden extension, collectively constitute its neck. The wood used to make the fretboard will usually differ from the wood in the rest of the neck. The bending stress on the neck is considerable, particularly when heavier gauge strings are used (see Strings and tuning), and the ability of the neck to resist bending (see Truss rod) is important to the guitar's ability to hold a constant pitch during tuning or when strings are fretted. The rigidity of the neck with respect to the body of the guitar is one determinant of a good instrument versus a poor one. The shape of the back of the neck can also vary, from a gentle "C" curve to a more pronounced "V" curve.

Neck joint or 'heel'

This is the point at which the neck meets the body of the guitar. In the traditional Spanish neck joint the neck and block are one piece with the sides inserted into slots cut in the block. Other necks are built separately and joined to the body either with a dovetail joint, mortise or flush joint. These joints are usually glued and can be reinforced with mechanical fasteners. Recently many manufacturers use bolt on fasteners. Bolt on neck joints were once associated only with less expensive instruments but now some top manufacturers and hand builders are using variations of this method. Some people believed that the Spanish style one piece neck/block and glued dovetail necks have better sustain, but testing has failed to confirm this. While most traditional Spanish style builders use the one piece neck/heel block, Fleta a prominent Spanish builder used a dovetail joint due to the influence of his early training in violin making. One reason for the introduction of the mechanical joints was to make it easier to repair necks. This is more of a problem with steel string guitars than with nylon strings which have about half the string tension. This is why nylon string guitars often don't include a truss rod either.

Body

The body of the instrument is a major determinant of the overall sound variety for acoustic guitars. The guitar top, or soundboard, is a finely crafted and engineered element often made of spruce, red cedar or mahogany. This thin (often 2 or 3 mm thick) piece of wood, strengthened by different types of internal bracing, is considered to be the most prominent factor in determining the sound quality of a guitar. The majority of the sound is caused by vibration of the guitar top as the energy of the vibrating strings is transferred to it. Different patterns of wood bracing have been used through the years by luthiers (Torres, Hauser, Ramírez, Fleta, and C.F. Martin being among the most influential designers of their times); to not only strengthen the top against collapsing under the tremendous stress exerted by the tensioned strings, but also to affect the resonation of the top. The back and sides are made out of a variety of woods such as mahogany, Indian rosewood and highly regarded Brazilian rosewood (Dalbergia nigra). Each one is chosen for its aesthetic effect and structural strength, and such choice can also play a significant role in determining the instrument's timbre. These are also strengthened with internal bracing, and decorated with inlays and purfling.

The body of a classical guitar is a resonating chamber which projects the vibrations of the body through a sound hole, allowing the acoustic guitar to be heard without amplification. The sound hole is normally a round hole in the top of the guitar (under the strings), though some may have different placement, shapes or multiple holes.

An instrument's maximum volume is determined by how much air it can move.

Binding, purfling and kerfing

The top, back and rim of a classical guitar body are very thin (1-2 mm), so a flexible piece of wood called kerfing (because it is often scored, or kerfed to allow it to bend with the shape of the rim) is glued into the corners where the rim meets the top and back. This interior reinforcement provides 5 to 20 mm or solid gluing area for these corner joints.

During final construction, a small section of the outside corners is carved or routed out and then filled with binding material on the outside corners and decorative strips of material next to the binding, which are called purfling. This binding serves to seal off the endgrain of the top and back. Binding and purfling materials are generally made of either wood or high quality plastic materials.

Bridge

The main purpose of the bridge on a classical guitar is to transfer the vibration from the strings to the soundboard, which vibrates the air inside of the guitar, thereby amplifying the sound produced by the strings. The bridge holds the strings in place on the body. Also, the position of the saddle, usually a strip of bone or plastic across the bridge upon which the strings rest, determines the distance to the nut (at the top of the fingerboard). This distance defines the positions of the harmonic nodes for the strings over the fretboard, and is the basis of intonation. Intonation refers to the property that the actual frequency of each string at each fret matches what those frequencies should be according to music theory. Because of the physical limitations of fretted instruments, intonation is at best approximate; thus, the guitar's intonation is said to be tempered. The twelfth, or octave, fret resides directly under the first harmonic node (half-length of the string), and in the tempered fretboard, the ratio of distances between consecutive frets is approximately 1.06 (see "Frets" above).

Sizes

The modern full size classical guitar has a scale size of around 650 mm (25.6 inches), with an overall instrument length of 965-1016 mm (38-40 inches). The scale size has remained consistently between 640-650 mm (25.2- 25.6 inches) since 650 mm was chosen by the originator of the instrument, Antonio de Torres. This length was probably chosen as twice the length of a violin string. As the guitar is tuned to one octave below that of the violin, the same size gut could be used for the 1st strings of both instruments.

Smaller scale instruments are produced to assist children in learning the instrument as the smaller scale leads to the frets being closer together making it easier for smaller hands. The scale size for the smaller guitars is usually in the range 484-578 mm (19-22.5 inches) with an instrument length of 785-915 mm (31-36 inches). Full size instruments are sometimes referred to as 4/4, while the smaller sizes are 3/4, 1/2 or 1/4.[8]

Scale size table

These sizes are not absolute as luthiers may choose variations around these nominal sizes.

- 4/4 650 mm (25.6 inches)

- 3/4 578 mm (22.75 inches)

- 1/2 522 mm (20.5 inches)

- 1/4 484 mm (19 inches)

Tuning

A variety of different tunings are used. The most common by far, which one could call the "standard tuning" is:

- eI - b - g - d - A - E

The above order, is the tuning from the 1st string (highest-pitched string e', physically visible as the bottom string when correctly holding a guitar) to the 6th string (lowest-pitched string E, physically visible as the top string, and hence usually comfortable to be plucked with the thumb).

| String | Sci. pitch | Helmholtz pitch | Interval from middle C | Semitones from A440 | Freq., if using an Equal temperament tuning (using ![\sqrt[12]{2} = 2^{(\frac{1}{12})}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/df714230e499a946802b0645b7af3fb8.png) ) ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (highest pitch) | E4 | e' | major third above | -5 | ![440 \rm{ Hz}\cdot (\sqrt[12]{2})^{-5} \approx](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/cf7f51dfa175e69df6e42746aad9c730.png) 329.63 Hz 329.63 Hz |

| 2nd | B3 | b | minor second below | -10 | ![440 \rm{ Hz}\cdot (\sqrt[12]{2})^{-10} \approx](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/b70b6c8ff2a24a8fdd4b2a87ba5b8b1d.png) 246.94 Hz 246.94 Hz |

| 3rd | G3 | g | perfect fourth below | -14 | ![440 \rm{ Hz}\cdot (\sqrt[12]{2})^{-14} \approx](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/e48a1bd19cca2d25356af6ee161a394f.png) 196.00 Hz 196.00 Hz |

| 4th | D3 | d | minor seventh below | -19 | ![440 \rm{ Hz}\cdot (\sqrt[12]{2})^{-19} \approx](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/531271dbdadb09a6adcf94dc929d8581.png) 146.83 Hz 146.83 Hz |

| 5th | A2 | A | minor tenth below | -24 | ![440 \rm{ Hz}\cdot (\sqrt[12]{2})^{-24} =](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/2a53406ba6a40083b2957ffc598373bb.png) 110 Hz 110 Hz |

| 6th (lowest pitch) | E2 | E | minor thirteenth below | -29 | ![440 \rm{ Hz}\cdot (\sqrt[12]{2})^{-29} \approx](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/d9d42719495f50f1c57bcd8c96481cc7.png) 82.41 Hz 82.41 Hz |

This tuning is such that neighboring strings are at most 5 semitones apart and this has a pragmatic reason which is outlined below - see Rationale.

A guitar using this tuning, enables one to properly tune the strings relative to one another, by the fact the 5th fret on one string is the same note as the next open string i.e. a 5th fret note on the 6th string is the same note as the 5th string, apart from between the third and second string, where the 4th fret note on the third string equals the second string. (The requirement is of course a well-crafted instrument with correct fret-placement.) This tuning has evolved to provide a good compromise between simple fingering for many chords and the ability to play common scales with minimal left hand movement. There are also a variety of commonly used alternate tunings.

Rationale of the tuning, in relation to frets and the left hand

The lateral position of the left hand determines which frets the fingers can reach (or more precisely: onto which frets the strings can be pushed down with the fingers). Keeping the left hand fixed, usually allows a span of 4 consecutive frets to be reachable (by using the following 4 consecutive left-hand fingers: index, middle, ring, small).

The tuning of the strings, is such, that one can play all chromatic notes occurring between 2 consecutive strings, by using the frets of the lower-tuned string without having to change the hand-position (I): Thus to move progressively from the pitch of a open lower string to the next higher string, we can use

- 1st fret of the lower string (with index finger)

- then the 2nd fret (with middle finger)

- then the 3rd fret (with ring finger)

- then the 4th fret (with little finger)

- then finally we reach the higher-pitched string (open string).

Since these are 5 steps (and consecutive frets are a semitone apart) it would be ideal if consecutive strings are tuned 5 semitones apart. In fact this is the very tuning that is most often used for the guitar, with the small exception that the 2nd and 3rd string are tuned 4 semitones apart:

| I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| open | 1st fret (index) | 2nd fret (middle) | 3rd fret (ring) | 4th fret (little) | |

| 1st string | e' | f' | f♯' | g' | a♭' |

| 2nd string | b | c' | c♯' | d' | e♭' |

| 3rd string | g | a♭ | a | b♭ | ... |

| 4th string | d | e♭ | e | f | f♯ |

| 5th string | A | B♭ | B | c | c♯ |

| 6th string | E | F | F♯ | G | A♭ |

| Chromatic note progression | |||||

It is important to note that the relative harmonic ratio (e.g. semitones-steps) between neighboring strings, does not change when moving up the frets. For example when considering the 1st and 2nd strings: e' to b (open strings) is like f' to c' (1st fret) is like f♯' to c♯' (2nd fret) etc.

The bass strings have a particular tuning which is harmonically related to the main typical keys in which most works are performed, since the bass strings can be plucked openly (providing a harmonic bass) at any time, irrespective of the lateral fret-position at which the left hand happens to be located.

The "lowest" fret-position is position I: this is when the left hand is positioned such that the index finger is over the 1st fret (the small finger can comfortably reach the 4th fret) The next-higher fret-position is position II: this is when the left hand is positioned closer to the guitar's body, such that the index finger is now over the 2nd fret (the small finger can comfortably reach the 5th fret) etc.

The higher the left hand's fret-position, the more a string is shortened when a string is pressed against an available higher fret: this results in a higher pitch from that string.

Playable/Reachable notes of the guitar

Important for the notes playable on the guitar, are

- the left-hand's position, since it determines the reachable frets

- the open strings, since they can always be played, irrespective of the left-hand's position. (This is of particular importance with regard to the bass strings.)

When moving the hand to such a higher-pitched fret-position, previously played lower notes are still playable without having to move the lateral hand-position back: this is possible by pressing a lower-pitched string towards an appropriate higher fret in the new higher fret-position. e.g. f#' on the 1st string in position I is usually fretted with the left-hand's middle finger. The same f#' pitch can be played in e.g. position V by using the 2nd string and fretting the 7th fret with the 3rd finger.

| I | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 1st string | e' | f' | f♯' | g' | ... | ... | |||

| 2nd string | e' | f' | f♯' | g' | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| V |

(1 = left-hand index finger; 2 = left-hand middle finger; etc.)

Thus one and the same note (in terms of pitch) can be played on different strings (by using appropriate frets), because the pitches of consecutive strings are only at most 5 semitones apart.

Bibliography

- Summerfield, Maurice, The Classical Guitar: Its Evolution, Players and Personalities since 1800 - 5th Edition, Blaydon : Ashley Mark Publishing Company, 2002.

- Various, Classical Guitar Magazine, Blaydon : Ashley Mark Publishing Company, monthly publication first published in 1982.

- Wade, Graham, Traditions of the Classical Guitar, London : Calder, 1980.

- Antoni Pizà: Francesc Guerau i el seu temps (Palma de Mallorca: Govern de les Illes Balears, Conselleria d'Educació i Cultura, Direcció General de Cultura, Institut d'Estudis Baleàrics, 2000) ISBN 84-89868-50-6

- The Guitar; Sinier de Ridder; Edizioni Il Salabue; ISBN 88-87618-09-7

References

- ↑ "The Guitar Family Tree". Dennis Cinelli.

- ↑ "Two String Trills". Tip of the Season. David Russell.

- ↑ "Interview with David Russell - mp3 (tracktime 10:35 - 24:00)". Two string trills. Classical Guitar Alive.

- ↑ "John Williams Interview with Austin Prichard-Levy". The Twang Box Dynasty.

- ↑ The Classical Mandolin by Paul Sparks (1995)

- ↑ Early Romantic Guitar

- ↑ Stalking the Oldest Six String Guitar

- ↑ How to Choose the correct size & type of Guitar for a Child

External links

- The Classical Guitar Blog

- Classical Guitarist Info

- Early Romantic Guitar Homepage

- guitarra.artelinkado Spanish portal with articles, etc. (Spanish)

- ProfessorString.com Guitar String Research

- Guitar acoustics

- Guitar Foundation of America Resources, artists, events, etc.

- Guitar Museum Classical Guitar Museum,(UK)

- Classical Guitar Blog

Scores (Sheetmusic)

in the public domain

- Boije Collection (The Music Library of Sweden)

-

- includes Sor, Giuliani, autographs by J.K. Mertz, etc.

- George C. Krick Collection of Guitar Music Gaylord Music Library, Washington University

-

- (Index - Online access to pdf, via "Connect to resource or more info")

- Advanced Search e.g. Field "All fields": Fernando Sor, and Field "URL (www link)": http NOT sheetmusicnow NOT freehandmusic NOT hebeonline

Photos and Images

- Photos of Romantic Guitars from 1796 to 1845 (Collection of Brigitte Zaczek, Vienna)

- Photos of historic guitars at the Museum Cité de la Musique in Paris

-

- Photothèque - search-phrase: Instrument de musique, ville ou pays : guitare

- Instruments et oeuvres d'art - search-phrase: Mot-clé(s) : guitare

- Facteurs d'instruments - search-phrase: Instrument fabriqué : guitare

- Instrumentarium Lipsiense Studia Instrumentorum Musicae

- Musée pictural de la guitare

- Images, Paintings

- Iconography

- Photos of various internal guitar bracings (www.gitarhangtechnika.hu)

- Photos of Festivals, Competitions, etc. (guitarra.artelinkado) (Spanish)

Radio Programs

- Classical Guitar Alive! - Archive - (by Tony Morris)

- A Arte do Violão (by Fábio Zanon), Rádio Cultura de São Paulo (Portuguese) (Brazil)

- Violão com Fábio Zanon, Rádio Cultura de São Paulo (Portuguese) (Brazil)

Articles and Texts

- The guitar and mandolin : biographies of celebrated players and composers for these instruments Philip James Bone (1914)

- Guitar And Lute Issues (Matanya Ophee)

- Miscellenious Articles (Guitarists in Italy, etc.)

|

||||||||

|

||||||||