Classical conditioning

Classical Conditioning (also Pavlovian or Respondent Conditioning) is a form of associative learning that was first demonstrated by Ivan Pavlov[1] . The typical procedure for inducing classical conditioning involves presentations of a neutral stimulus along with a stimulus of some significance. The neutral stimulus could be any event that does not result in an overt behavioral response from the organism under investigation. Pavlov referred to this as a Conditioned Stimulus (CS). Conversely, presentation of the significant stimulus necessarily evokes an innate, often reflexive, response. Pavlov called these the Unconditioned Stimulus (US) and Unconditioned Response (UR), respectively. If the CS and the US are repeatedly paired, eventually the two stimuli become associated and the organism begins to produce a behavioral response to the CS. Pavlov called this the Conditioned Response (CR).

Popular forms of classical conditioning that are used to study neural structures and functions that underlie learning and memory include fear conditioning, eyeblink conditioning, and Classical Conditioning of Aplysia gill and siphon withdrawal reflex.

Contents |

History

Pavlov's experiment

The original and most famous example of classical conditioning involved the salivary conditioning of Pavlov's dogs. During his research on the physiology of digestion in dogs, Pavlov noticed that, rather than simply salivating in the presence of meat powder (an innate response to food that he called the unconditioned response), the dogs began to salivate in the presence of the lab technician who normally fed them. Pavlov called these psychic secretions. From this observation he predicted that, if a particular stimulus in the dog’s surroundings were present when the dog was presented with meat powder, then this stimulus would become associated with food and cause salivation on its own. In his initial experiment, Pavlov used bells to call the dogs to their food and, after a few repetitions, the dogs started to salivate in response to the bell. Thus, a neutral stimulus (bell) became a conditioned stimulus (CS) as a result of consistent pairing with the unconditioned stimulus (US - meat powder in this example). Pavlov referred to this learned relationship as a conditional reflex (now called Conditioned Response).

Types

Forward conditioning

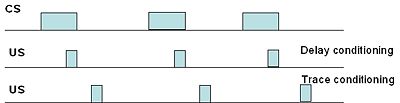

During forward conditioning the onset of the CS precedes the onset of the US. Two common forms of forward conditioning are delay and trace conditioning.

Delay conditioning

The start of the US is delayed relative to the start of the CS. In this procedure, the US is present during a shorter interval in the duration of the CS, terminating at the same time as the CS. The delay refers to the interstimulus interval (ISI), and is determined by the type of classical conditioning. During eyeblink conditioning, ISIs in the range of 100 to 750 msec are considered short while in taste aversion conditioning, ISIs in the range of minutes to hours are considered short.

Trace conditioning

During trace conditioning the CS and US do not overlap. Instead, the CS is presented, a period of time is allowed to elapse during which no presented, and then the US is presented. The stimulus free period is called the trace interval. It may also be called the "conditioning interval"

Simultaneous conditioning

During simultaneous conditioning, the CS and US are presented and terminate at the same time.

Backward conditioning

Backward conditioning occurs when a conditioned stimulus immediately follows an unconditioned stimulus. Unlike traditional conditioning models, in which the conditioned stimulus precedes the unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned response tends to be inhibitory. This is because the conditioned stimulus serves as a signal that the unconditioned stimulus has ended, rather than a reliable method of predicting the future occurrence of the unconditioned stimulus.

The onset of the US precedes the onset of the CS. Rather than being a reliable predictor of an impending US (such as in Forward Conditioning), the CS actually serves as a signal that the US has ended. As a result, the CR is said to be inhibitory

Temporal conditioning

The US is presented at regularly timed intervals, and CR acquisition is dependent upon correct timing of the interval between US presentations. The background, or context, can serve as the CS in this example.

Unpaired conditioning

The CS and US are not presented together. Usually they are presented as independent trials that are separated by a variable, or pseudo-random, interval. This procedure is used to study non-associative behavioral responses, such as sensitization.

CS-alone extinction

The CS is presented in the absence of the US. This procedure is usually done after the CR has been acquired through Forward conditioning training. Eventually, the CR frequency is reduced to pre-training levels.

Procedure variations

In addition to the simple procedures described above, some classical conditioning studies are designed to tap into more complex learning processes. Some common variations are discussed below.

Classical discrimination/reversal conditioning

In this procedure, two CSs and one US are typically used. The CSs may be the same modality (such as lights of different intensity), or they may be different modalities (such as auditory CS and visual CS). In this procedure, one of the CSs is designated CS+ and its presentation is always followed by the US. The other CS is designated CS- and its presentation is never followed by the US. After a number of trials, the organism learns to discriminate CS+ trials and CS- trials such that CRs are only observed on CS+ trials.

During Reversal Training, the CS+ and CS- are reversed and subjects learn to suppress responding to the previous CS+ and show CRs to the previous CS-.

Classical ISI discrimination conditioning

This is a discrimination procedure in which two different CSs are used to signal two different interstimulus intervals. For example, a dim light may be presented 30 seconds before a US, while a very bright light is presented 2 minutes before the US. Using this technique, organisms can learn to perform CRs that are appropriately timed for the two distinct CSs.

Latent inhibition conditioning

In this procedure, a CS is presented several times before paired CS-US training commences. The pre-exposure of the subject to the CS before paired training slows the rate of CR acquisition relative to organisms that are not CS pre-exposed. Also see Latent inhibition for applications.

Conditioned inhibition conditioning

Three phases of conditioning are typically used:

- Phase 1:

-

- A CS (CS+) is paired with a US until asymptotic CR levels are reached.

- Phase 2:

-

- CS+/US trials are continued, but interspersed with trials on which the CS+ in compound with a second CS, but not with the US (i.e., CS+/CS- trials). Typically, organisms show CRs on CS+/US trials, but suppress responding on CS+/CS- trials.

- Phase 3:

-

- In this retention test, the previous CS- is paired with the US. If conditioned inhibition has occurred, the rate of acquisition to the previous CS- should be impaired relative to organisms that did not experience Phase 2.

Blocking

This form of classical conditioning also involves three phases.

- Phase 1:

-

- A CS (CS1) is paired with a US.

- Phase 2:

Applications

Little Albert

John B. Watson, founder of behaviourism, demonstrated classical conditioning empirically through experimentation using the Little Albert experiment in which a child ("Albert") was presented with a white rat to which was later paired with a loud noise. As the trials progressed, the child began showing signs of distress at the sight of the rat and other white objects, demonstrating that conditioning had taken place.

Behavioral therapies

In human psychology, implications for therapies and treatments using classical conditioning differ from operant conditioning. Therapies associated with classical conditioning are aversion therapy, flooding and systematic desensitization.

Classical conditioning is short-term, usually requiring less time with therapists and less effort from patients, unlike humanistic therapies. The therapies mentioned are designed to cause either aversive feelings toward something, or to reduce unwanted fear and aversion. Classical conditioning is based on a repetitive behaviour system.

Aversion therapy

Aversion therapy is a form of psychological therapy that is designed to eliminate unwanted behavior by associating an aversive stimulus with the behavior. Because the aversive stimulus performs as a US and produces a UR, the association between the stimulus and behaviour leads to the same consequences each time. Successful treatment ends in the patient losing the compulsion to engage in the unwanted behaviors. This sort of treatment has been used to treat alcoholism as well as drug addiction.[2]

Exposure therapies

Exposure therapy involves systematically exposing individuals to a feared object or situation until the fear has been extinguished. Generally the therapy will involve the construction of a fear hierarchy of events that gradually escalate from least anxiety-evoking, to most anxiety evoking. Through the process of systematic exposure, the anxiety felt is lessened or eliminated. Various forms of exposure therapy has been shown to be effective for a variety of psychological diagnoses, including Specific Phobia, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Systematic desensitization involves the utilization of exposure therapy, paired with relaxation techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing.

Flooding similarly exposes the patient to a feared object or situation, but involves no hierarchy. Instead, the patient is exposed to their worst possible fear (within realistic safety limitations) and prevented from escaping the situation until the fear is eliminated. Evidence suggests that flooding is not the most effective form of exposure therapy.

Though the therapies are frequently used for treatment of anxiety, they can also be used to treat drug addiction or other unwanted behavior.

Theories of classical conditioning

There are two competing theories of how classical conditioning works. The first, stimulus-response theory, suggests that an association to the unconditioned stimulus is made with the conditioned stimulus within the brain, but without involving conscious thought. The second theory stimulus-stimulus theory involves cognitive activity, in which the conditioned stimulus is associated to the concept of the unconditioned stimulus, a subtle but important distinction.

Stimulus-response theory, referred to as S-R theory, is a theoretical model of behavioral psychology that suggests humans and other animals can learn to associate a new stimulus- the conditioned stimulus (CS)- with a pre-existing stimulus - the unconditioned stimulus (US), and can think, feel or respond to the CS as if it were actually the US.

The opposing theory, put forward by cognitive behaviorists, is stimulus-stimulus theory (S-S theory). Stimulus-stimulus theory, referred to as S-S theory, is a theoretical model of classical conditioning that suggests a cognitive component is required to understand classical conditioning and that stimulus-response theory is an inadequate model. It proposes that a cognitive component is at play. S-R theory suggests that an animal can learn to associate a conditioned stimulus (CS) such as a bell, with the impending arrival of food termed the unconditioned stimulus, resulting in an observable behavior such as salivation. Stimulus-stimulus theory suggests that instead the animal salivates to the bell because it is associated with the concept of food, which is a very fine but important distinction.

To test this theory, psychologist Robert Rescorla undertook the following experiment [3]. Rats learned to associate a loud noise as the unconditioned stimulus, and a light as the conditioned stimulus. The response of the rats was to freeze and cease movement. What would happen then if the rats were habituated to the US? S-R theory would suggest that the rats would continue to respond to the US, but if S-S theory is correct, they would be habituated to the concept of a loud sound (danger), and so would not freeze to the CS. The experimental results suggest that S-S was correct, as the rats no longer froze when exposed to the signal light. [4] His theory still continues and is applied in everyday life.

See also

- Behaviorism

- Blocking effect

- Conditioned taste aversion

- Eyeblink conditioning

- Fear conditioning

- Latent inhibition

- Learned helplessness

- Nocebo

- Operant conditioning

- Placebo (origins of technical term)

- Quantitative Analysis of Behavior

- Rescorla-Wagner model of conditioning

- Reward system

- Preparedness (learning)

- Second-order conditioning

- Taste aversion

- Edwin B. Twitmyer

References

- ↑ Pavlov, I. P. (1927/1960). Conditional Reflexes. New York: Dover Publications (the 1960 edition is an unaltered republication of the 1927 translation by Oxford University Press http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Pavlov/).

- ↑ John P.J.Pinel, Biopsychology 2006 6th edition

- ↑ Rescorla, R (1973) Effect of US habituation following conditioning. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 82 17-143

- ↑ Psychology, Peter Gray Third Edition pg 121

Further reading

- Dayan, P., Kakade, S., & Montague, P.R. (2000). Learning and selective attention. Nature Neuroscience 3, 1218 - 1223. Full text

- Kirsch, I., Lynn, S.J., Vigorito, M. & Miller, R.R. (2004). The role of cognition in classical and operant conditioning. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60, 369 - 392. Full text

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex (translated by G. V. Anrep). London: Oxford University Press.

- Rescorla, R. A., & Wagner, A. R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning. Varitions in effectiveness of reinforcement and non-reinforcement. In A. Black & W. F. Prokasky, Jr. (eds.), Classical Conditioning II New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

External links

|

|||||||||||