Cistercians

The Order of Cistercians (OCist; Latin: Cistercienses), sometimes called the White Monks (from the colour of the habit, over which a black scapular or apron is sometimes worn) is a Roman Catholic religious order of enclosed monks. The first Cistercian abbey was founded by Robert of Molesme in 1098, at Cîteaux Abbey near Dijon, France. Two others, Saint Alberic of Citeaux and Saint Stephen Harding, are considered co-founders of the order, and Bernard of Clairvaux is associated with the fast spread of the order during the 12th century.

The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to literal observance of the Rule of St Benedict. Rejecting the developments the Benedictines had undergone, the monks tried to reproduce life exactly as it had been in Saint Benedict's time; indeed in various points they went beyond it in austerity. The most striking feature in the reform was the return to manual labour, especially field-work, a special characteristic of Cistercian life. The Cistercians became the main force of technological diffusion in medieval Europe.

The Cistercians were badly affected in England by the Protestant Reformation, the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII, the French Revolution in continental Europe, and the revolutions of the 18th century, but some survived and the order recovered in the 19th century. In 1891 certain abbeys formed a new Order called Trappists (Ordo Cisterciensium Strictioris Observantiae - OCSO), which today exists as an order distinct from the Common Observance.

Contents |

History

Foundation

In 1098 a band of 21 Cluniac monks left their abbey of Molesme in Burgundy and followed their abbot, Robert of Molesme (1027–1111), to establish a new monastery. The group was looking to cultivate a monastic community in which monks could carry out their lives in stricter observance of the Rule of St Benedict. On March 21, 1098, the small faction acquired a plot of marsh land just south of Dijon called Cîteaux (Latin: "Cistercium"), given to them expressly for the purpose of founding their Novum Monasterium.[1]

During the first year the monks set about constructing lodging areas and farmed the lands. In the interim, there was a small chapel nearby which they used for Mass. Soon the monks in Molesme began petitioning Pope Urban II to return their abbot to them. The case was passed down to Archbishop Hugues who passed the issue on down to the local bishops. Robert was then instructed to return to his position as abbot in Molesme, where he remained for the rest of his days. A good number of the monks who helped found Cîteaux returned with him to Molesme, so that only a few remained. The remaining monks elected Prior Alberic as their abbot, under whose leadership the abbey would find its grounding. Robert had been the idealist of the order, and Alberic was their builder.

Upon assuming the role of abbot, Alberic moved the site of the fledgling community near a brook a short distance away from the original site. Alberic discontinued the use of Benedictine black garments in the abbey and clothed the monks in white cowls (undyed wool). He returned the community to the original Benedictine ideal of work and prayer, dedicated to the ideal of charity and self sustenance. Alberic also forged an alliance with the Dukes of Burgundy, working out a deal with Duke Odo the donation of a vineyard (Meursault) as well as stones with which they built their church. The church was sanctified and dedicated to The Virgin Mary on November 16, 1106 by the Bishop of Chalon sur Saône.[2]

On January 26, 1108 Alberic died and was soon succeeded by Stephen Harding, the man responsible for carrying the order into its crucial phase. Stephen created the Cistercian constitution, called Carta Caritatis (the Charter of Charity). Stephen also acquired farms for the abbey in order to ensure its survival and ethic, the first of which was Clos Vougeot. He handed over the west wing of the monastery to a large group of lay brethren to cultivate the farms.

Polity

The lines of the Cistercian polity were adumbrated by Alberic, but it received its final form at a meeting of the abbots in the time of Stephen Harding, when was drawn up the Carta Caritatis,[3][4] a document which arranged the relations between the various houses of the Cistercian order, and exercised a great influence also upon the future course of western monachism. From one point of view, it may be regarded as a compromise between the primitive Benedictine system, in which each abbey was autonomous and isolated, and the complete centralization of Cluny, where the Abbot of Cluny was the only true superior in the body.

On the one hand, Citeaux maintained the independent organic life of the houses: each abbey had its own abbot elected by its own monks, its own community belonging to itself and not to the order in general, and its own property and finances administered without interference from outside. On the other hand, all the abbeys were subjected to the general chapter, which met yearly at Cîteaux and consisted of the abbots only. The Abbot of Cîteaux was the president of the chapter and of the order, and the visitor of each and every house. He had a predominant influence and the power of enforcing everywhere exact conformity to Cîteaux in all details of the exterior life observance, chant, and customs. The principle was that Cîteaux should always be the model to which all the other houses had to conform. In case of any divergence of view at the chapter, the side taken by the Abbot of Cîteaux was always to prevail.[5]

Spread: 1111—1152

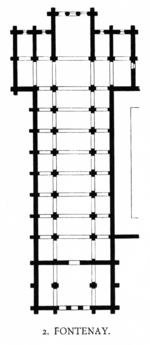

By 1111 the ranks had grown sufficiently at Cîteaux, and Stephen sent a group of 12 monks to start a "daughter house", a new community dedicated to the same ideals of the strict observance of Saint Benedict. It was built in Chalon sur Saône in La Ferté on May 13, 1113.[6] Also in 1113, Bernard of Clairvaux arrived at Cîteaux with 30 others to join the monastery. In 1114 another daughter house was founded, Pontigny Abbey. Then, in 1115 Bernard founded Clairvaux, followed by Morimond in the same year. Later, Preuilly, La Cour-Dieu, Bouras, Cadouin and Fontenay were established.

In November 1128, with the aid of William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, Waverly Abbey was founded in Surrey, England.[7] Five houses were founded from Waverly Abbey before 1152, and some of these had themselves produced offshoots.[7] Thirteen Cistercian monasteries, all in remote sites, were founded in Wales between 1131 and 1226.[8] The first of these was Tintern Abbey, which was sited in a remote river valley, and depended largely on its agricultural and pastoral activities for survival.[8]

In Yorkshire, Rievaulx Abbey was founded from Clairvaux in 1131, on a small property "in a place of horror and dreary solitude".[7] This land was donated by Walter Espec, with the support of Thurstan, Archbishop of York.[7] By 1143, three hundred monks had entered Rievaulx, including the famous St Ælred, who became known as the "St Bernard of England".[7] From Rievaulx was founded Melrose Abbey, the earliest Cistercian monastery in Scotland.[9] Located in Roxburghshire, it was built in 1136 by King David I of Scotland, and completed in less than ten years.[9] Another important offshoot of Rievaulx was Revesby Abbey in Lincolnshire.[7]

Fountains abbey was founded in 1132 by Benedictine monks from St Mary's Abbey, York, who desired a return to the austere Rule of St Benedict.[7] After many struggles and great hardships, St Bernard agreed to send a monk from Clairvaux to instruct them, and in the end they prospered exceedingly.[7] Before 1152, Fountains had many offshoots, of which Newminster Abbey (1137) and Meaux Abbey (1151) are the most famous.[7]

In the spring of 1140, St Malachy, Archbishop of Armagh, visited Clairvaux, becoming a personal friend of St Bernard and an admirer of the Cistercian rule.[10] He left four of his companions to be trained as Cistercians, and returned to Ireland to introduce Cistercianism there.[10] St Bernard viewed the Irish at this time as being in the "depth of barbarism":

... never had he found men so shameful in their morals, so wild in their rites, so impious in their faith, so barbarous in their laws, so stubborn in discipline, so unclean in their life. They were Christians in name, in fact they were pagans.[11]

Mellifont Abbey was founded in County Louth in 1142. Thence were founded the affiliated monasteries of Bective Abbey in County Meath (1147), Inishlounaght in County Tipperary (1147-1148), Baltinglass in County Wicklow (1148), Monasteranenagh in County Limerick (1148), and Kilbeggan in County Westmeath (1150).[12] Malachy's intensive pastoral activity was highly successful:

Barbarous laws disappeared, Roman laws were introduced: everywhere ecclesiastical customs were received and the contrary rejected… In short all things were so changed that the word of the Lord may be applied to this people: Which before was not my people, now is my people.[13]

Meanwhile, the Cistercian influence in the Church more than kept pace with this material expansion, so that in 1145, St Bernard saw one of his monks ascend the papal chair as Pope Eugene III. A great reinforcement to the order was the merger of the Savigniac houses with the Cistercians, at the instance of Eugene III.[7] Thirteen English abbeys, of which the most famous were Furness Abbey and Jervaulx Abbey, thus adopted the Cistercian rule.[7] In Dublin, the two Savigniac houses of Erenagh and St Mary's became Cistercian.[12] It was in the latter case that medieval Dublin acquired a Cistercian monastery in the very unusual suburban location of Oxmantown, with its own private harbour called The Pill.[14]

By 1152, there were fifty-four Cistercian monasteries in England, some few of which, had been founded directly from the Continent.[7] Overall, there were 333 Cistercian abbeys in Europe 1152 – so many that a halt was put to this expansion.[15]

Nearly half of the houses had been founded, directly or indirectly, from Clairvaux, so great was St Bernard's influence and prestige. Indeed he has come almost to be regarded as the founder of the Cistercians, who have often been called Bernardines. From this solid base the order spread all over western Europe; into Germany, Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Croatia, Italy (where the Certosa di Pavia is their most famous edifice), Sicily, Poland, Hungary, Romania (Kerz), Norway, Sweden, Spain and Portugal (where some of the houses, like the Monastery of Alcobaça, were of almost incredible magnificence). One of the most important libraries of the Cistercians was in Salem, Germany. By the end of the 13th century, the Cistercian houses numbered 500.[16] At the order's height in the 15th century, it would have nearly 750 houses.

Construction of abbeys

Architecturally speaking the Cistercian monasteries and churches, owing to their pure style, may be counted among the most beautiful relics of the Middle Ages.[7] The building projects of the Church at this time showed an ambition for the colossal, with vast amounts of stone being quarried, and the same was true of the Cistercian projects.[17] Foigny Abbey was 98 metres (320 ft) long, and Vaucelles Abbey was 132 metres (430 ft) long.[17] Monastic buildings came to be constructed entirely of stone, right down to the most humble of buildings. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Cistercian barns consisted of a stone exterior, divided into nave and aisles either by wooden posts or by stone piers.[18]

The Cistercians acquired a reputation in the difficult task of administering the building sites for abbeys and cathedrals.[19] St Bernard's own brother, Achard, is known to have supervised the construction of many abbeys, such as Himmerod Abbey in the Rhineland.[19] Others were Raoul at Saint-Jouin-de-Marnes, who later became abbot there; Geoffrey d'Aignay, sent to Fountains Abbey in 1133; and Robert, sent to Mellifont Abbey in 1142.[19] On one occasion the Abbot of La Trinité at Vendôme loaned a monk named John to the Bishop of Le Mans, Hildebert de Lavardin, for the building of a cathedral; after the project was completed, John refused to return to his monastery.[19]

The Cistercians "made it a point of honour to recruit the best stonecutters", and as early as 1133, St Bernard was hiring workers to help the monks erect new buildings at Clairvaux.[20] It is from the 12th century Byland Abbey in Yorkshire that the oldest recorded example of architectural tracing dates is found.[21] Tracings were architectural drawings painted in stone, to a depth of 2-3 mm, showing architectural detail to scale.[21] The first tracing in Byland illustrates a west rose window, while the second depicts the central part of that same window.[21] Later, an illustration from the latter half of the 16th century would show monks working alongside other craftsmen in the construction of Schönau Abbey.[20]

Monastic life and technological diffusion

The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to a literal observance of St Benedict's rule: how literal may be seen from the controversy between St. Bernard and Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny.[22] The Cistercians rejected alike all mitigations and all developments, and tried to reproduce the life exactly as it had been in St Benedict's time, indeed in various points they went beyond it in austerity. At the beginning they renounced all sources of income arising from benefices, tithes, tolls and rents, and depended for their income wholly on the land. The most striking feature in the reform was the return to manual labour, and especially to field-work, which became a special characteristic of Cistercian life.

To make time for this work they cut away the accretions to the divine office which had been steadily growing during three centuries, and which in Cluny and the other Benedictine monasteries had come to exceed greatly in length the regular canonical office: one only of these accretions did they retain, the daily recitation of the Office of the Dead.[23]

It was as agriculturists and horse and cattle breeders that, after the first blush of their success and before a century had passed, the Cistercians exercised their chief influence on the progress of civilisation in the later Middle Ages: they were the great farmers of those days, and many of the improvements in the various farming operations were introduced and propagated by them, and this is where the importance of their extension in northern Europe is to be estimated. They developed an organised system for selling their farm produce, cattle and horses, and notably contributed to the commercial progress of the countries of western Europe. To the wool and cloth trade, which was especially fostered by the Cistercians, England was largely indebted for the beginnings of her commercial prosperity.[7]

Farming operations on so extensive a scale could not be carried out by the monks alone, whose choir and religious duties took up a considerable portion of their time; and so from the beginning the system of lay brothers was introduced on a large scale. The lay brothers were recruited from the peasantry and were simple uneducated men, whose function consisted in carrying out the various fieldworks and plying all sorts of useful trades: they formed a body of men who lived alongside of the choir monks, but separate from them, not taking part in the canonical office, but having their own fixed round of prayer and religious exercises. They were never ordained, and never held any office of superiority. It was by this system of lay brothers that the Cistercians were able to play their distinctive part in the progress of European civilisation.

According to the medievalist Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor."[24] Waterpower was used for crushing wheat, sieving flour, fulling cloth and tanning – a "level of technological achievement [that] could have been observed in practically all" of the Cistercian monasteries.[25]

In Spain, one of the earliest surviving Cistercian houses – the Real Monasterio de Nuestra Senora de Rueda in the Aragon region – is a good example of early hydrologic engineering, using a large waterwheel for power and an elaborate hydrological circulation system for central heating.

The Cistercians are known to have been skilled metallurgists, and knowledge of their technological advances was transmitted by the order.[26] Iron ore deposits were often donated to the monks along with forges to extract the iron, and within time surpluses were being offered for sale. The Cistercians became the leading iron producers in Champagne, from the mid-13th century to the 17th century, also using the phosphate-rich slag from their furnaces as an agricultural fertiliser.[27] As the historian Alain Erlande-Brandenburg writes:

The quality of Cistercian architecture from the 1120s onwards is related directly to the Order's technological inventiveness. They placed importance on metal, both the extraction of the ore and its subsequent processing. At the abbey of Fontenay the forge is not outside, as one might expect, but inside the monastic enclosure: metalworking was thus part of the activity of the monks and not of the lay brothers. This spirit accounted for the progress that appeared in spheres other than building, and particularly in agriculture.

It is probable that this experiment spread rapidly; Gothic architecture cannot be understood otherwise.[28]

Later History

The first Cistercian abbey in Bohemia was founded in Sedlec near Kutná Hora in 1158. In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the Cistercian order played an essential role in the politics and diplomacy of the late Přemyslid and early Luxembourg state, as reflected in the Chronicon Aulae Regiae, a chronicle written by Otto and Peter of Zittau, abbots of the Zbraslav abbey (Latin: Aula Regia, ie, Royal Hall; today situated on the southern outskirts of Prague), founded in 1292 by the king of Bohemia and Poland, Wenceslas II. The order also played the main role in the early Gothic art of Bohemia; one of the outstanding pieces of Cistercian architecture is the Alt-neu Shul, Prague.

It often happened that the number of lay brothers became excessive and out of proportion to the resources of the monasteries, there being sometimes as many as 200, or even 300, in a single abbey. On the other hand, at any rate in some countries, the system of lay brothers in course of time worked itself out; thus in England by the close of the 14th century it had shrunk to relatively small proportions, and in the 15th century the régime of the English Cistercian houses tended to approximate more and more to that of the Black Monks.

For a hundred years, till the first quarter of the 13th century, the Cistercians supplanted Cluny as the most powerful order and the chief religious influence in western Europe. But then in turn their influence began to wane, chiefly, no doubt, because of the rise of the mendicant orders, who ministered more directly to the needs and ideas of the new age. But some of the reasons of Cistercian decline were internal.

In the first place, there was the permanent difficulty of maintaining in its first fervour a body embracing hundreds of monasteries and thousands of monks, spread all over Europe; and as the Cistercian very raison d'être consisted in its being a reform, a return to primitive monachism, with its field-work and severe simplicity, any failures to live up to the ideal proposed worked more disastrously among Cistercians than among mere Benedictines, who were intended to live a life of self-denial, but not of great austerity.

Relaxations were gradually introduced in regard to diet and to simplicity of life, and also in regard to the sources of income, rents and tolls being admitted and benefices incorporated, as was done among the Benedictines; the farming operations tended to produce a commercial spirit; wealth and splendour invaded many of the monasteries, and the choir monks abandoned field-work.

The later history of the Cistercians is largely one of attempted revivals and reforms. The general chapter for long battled bravely against the invasion of relaxations and abuses.

The English Reformation was disastrous for the Cistercians in England, as Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries saw the confiscation of church land throughout the country. Laskill, an outstation of Rievaulx Abbey and the only medieval blast furnace so far identified in Great Britain, was the one of the most efficient blast furnaces of its time.[29] Slag from contemporary furnaces contained a substantial concentration of iron, whereas the slag of Laskill was low in iron content, and is believed to have produced cast iron with efficiency similar to a modern blast furnace.[30][29] The monks may have been on the verge of building dedicated furnaces for the production of cast iron,[29] but the furnace did not survive Henry's Dissolution in the late 1530s, and the type of blast furnace pioneered there did not spread outside Rievaulx.[31] Some historians believe that the suppression of the English monasteries may have stamped out an industrial revolution.[29]

After the Protestant Reformation

In 1335, Pope Benedict XII, himself a Cistercian, had promulgated a series of regulations to restore the primitive spirit of the order, and in the 15th century various popes endeavoured to promote reforms. All these efforts at a reform of the great body of the order proved unavailing; but local reforms, producing various semi-independent offshoots and congregations, were successfully carried out in many parts in the course of the 15th and 16th centuries.

In the 17th another great effort at a general reform was made, promoted by the pope and the king of France; the general chapter elected Richelieu (commendatory) abbot of Cîteaux, thinking he would protect them from the threatened reform. In this they were disappointed, for he threw himself wholly on the side of reform. So great, however, was the resistance, and so serious the disturbances that ensued, that the attempt to reform Cîteaux itself and the general body of the houses had again to be abandoned, and only local projects of reform could be carried out.

In the 16th century had arisen the reformed congregation of the Feuillants, which spread widely in France and Italy, in the latter country under the name of Improved Bernardines. The French congregation of Sept-Fontaines (1654) also deserves mention. In 1663 de Rancé reformed La Trappe (see Trappists).

The Reformation, the ecclesiastical policy of Joseph II, the French Revolution, and the revolutions of the 18th century, almost wholly destroyed the Cistercians; but some survived, and since the beginning of the last half of the 19th century there has been a considerable recovery. Mahatma Gandhi visited a Trappist abbey near Durban in 1895, and wrote an extensive description of the order:

"The settlement is a quiet little model village, owned on the truest republican principles. The principle of liberty, equality, and fraternity is carried out in its entirety. Every man is a brother, every woman a sister. The monks number about 120 on the settlement, and the nuns, or the sisters as they are called, number about sixty… None may keep any money for private use. All are equally rich or poor…

"A Protestant clergyman said to his audience that Roman Catholics were weakly, sickly, and sad. Well, if the Trappists are any criterion of what a Roman Catholic is, they are, on the contrary, healthy and cheerful. Wherever we went, a beaming smile and a lowly bow greeted us, we saw a brother or a sister. Even while the guide was decanting on the system he prized so much, he did not at all seem to consider the self-chosen discipline a hard yoke to bear. A better instance of undying faith and perfect implicit obedience could not well be found anywhere else."

At the beginning of 20th century they were divided into three bodies:

- The Common Observance, with about 30 monasteries and 800 choir monks, the large majority being in Austria-Hungary; they represent the main body of the order and follow a mitigated rule of life; they do not carry on field-work, but have large secondary schools, and are in manner of life little different from fairly observant Benedictine Black Monks; of late, however, signs are not wanting of a tendency towards a return to older ideals;

- The Middle Observance, embracing some dozen monasteries and about 150 choir monks;

- The Strict Observance, or Trappists, with nearly 60 monasteries, about 1600 choir monks and 2000 lay brothers.

There has also always been a large number of Cistercian nuns; the first nunnery was founded in the diocese of Langres, 1125; at the period of their widest extension there are said to have been 900 nunneries, and the communities were very large. The nuns were devoted to contemplation and also did field-work. In Spain and France certain Cistercian abbesses had extraordinary privileges. Numerous reforms took place among the nuns. The best known of all Cistercian convents was probably Port-Royal, reformed by Angélique Arnaud, and associated with the story of the Jansenist controversy.

Cistercians today

Organisation

Cistercian monasteries have continued to spread, with many founded outside Europe in the 20th century. In particular, the number of Trappist monasteries throughout the world has more than doubled over the past 60 years: from 82 in 1940 to 127 in 1970, and 169 at the beginning of the 21st century.[32] In 1940, there were six Trappist monasteries in Asia and the Pacific, only one Trappist monastery in Africa, and none in Latin America.[32] Now there are 13 in Central and South America, 17 in Africa, and 23 in Asia and the Pacific.[32] In general, these communities are growing faster than those in other parts of the world.[32]

Over the same period, the total number of monks and nuns in the Order decreased by about 15%.[32] There are approximately 2500 Trappist monks and 1800 Trappist nuns in the world today.[32] There are on average 25 members per community - less than half those in former times.[32] As of 2005, there are 101 monasteries of monks and 70 of nuns.[33] Of these, there are twelve monasteries of monks and five of nuns in the United States.[33]

The abbots and abbesses of each branch meet every three years at the Mixed General Meeting, chaired by the Abbot General, to make decisions concerning the welfare of the Order.[33] Between these meetings the Abbot General and his Council, who reside in Rome, are in charge of the Order's affairs.[33] The present Abbot General is Dom Bernardo Olivera of Azul, Argentina.[33]

Monastic life

At the time of monastic profession, five or six years after entering the monastery, candidates promise "conversion" — fidelity to monastic life, which includes an atmosphere of silence.[34] Cistercian monks and nuns, in particular Trappists, have a reputation of being silent, which has led to the public idea that they take a Vow of silence.[34] This has actually never been the case, although silence is an implicit part of an outlook shared by Cistercian and Benedictine monasteries.[34] In a Cistercian monastery, there are three reasons for speaking:

functional communication at work or in community dialogues, spiritual exchange with one’s superiors or with a particular member of the community on different aspects of one’s personal life, and spontaneous conversation on special occasions. These forms of communication are integrated into the discipline of maintaining a general atmosphere of silence, which is an important help to continual prayer.[34]

Many Cistercian monasteries produce goods such as cheese, bread and other foodstuffs. Many monasteries in Belgium and the Netherlands, such as Orval Abbey and Westvleteren Abbey, brew beer both for the monks and for sale to the general public. Trappist beers contain residual sugars and living yeast, and, unlike conventional beers, will improve with age.[35] These have become quite famous and are considered by many beer critics to be among the finest in the world.[35]

In the United States, many Cistercian monasteries support themselves through argriculture, forestry and rental of farmland. The Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Spring Bank, in Sparta, Wisconsin, supports itself with financial investing, real estate, and a group called "Laser Monks";[36] which provides recycled laser toner and ink jet cartridges.[37] The monks of New Melleray Abbey, rural Peosta, Iowa produce caskets for both themselves and sale to the public.

Legacy

- See also: List of Cistercian abbeys in Britain and List of monasteries dissolved by Henry VIII of England

Cistercian architecture has made an important contribution to European civilisation. The abbeys of France and England are fine examples of Romanesque and Gothic architecture. In Poland, the former Cistercian monastery of Pelplin Cathedral is an important example of brick gothic. Wąchock abbey is one of the most valuable examples of Polish Romanesque architecture. The largest Cistercian complex, the Abbatia Lubensis (Lubiąż, Poland), is a masterpiece of baroque architecture and the second largest Christian architectural complex in the world.

The following monasteries and abbeys are recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- Abbey of Fontenay, Côte-d'Or, France

- Fountains Abbey, North Yorkshire, England

- Monastery of Alcobaça, Portugal

- Poblet Monastery, Catalonia, Spain

See also

- Cistercian Martyrs of Atlas

Notes

- ↑ Tobin, pp 29, 33, 36.

- ↑ Tobin, pp 37-38.

- ↑ Latin text: [1]

- ↑ Migne, Patrol. Lat. clxvi. 1377

- ↑ See F. A. Gasquet, Sketch of Monastic Constitutional History, pp. xxxv-xxxviii, prefixed to English trans. Of Montalemberts Monks of the West, ed. 1895

- ↑ Tobin, pp 46

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 "Cistercians in the British Isles". Catholic Encyclopedia. NewAdvent.org. Retrieved on 2008-06-18.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dykes, p76-78

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Abbey of Melrose

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Watt, p 20

- ↑ Watt, p 17

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Watt, p 21

- ↑ Watt, p 17-18

- ↑ Clarke, p 42-43

- ↑ Logan, p 139

- ↑ Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance (Trappists): Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Erlande-Brandenburg, p 32-34

- ↑ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 28

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Erlande-Brandenburg, p 50

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Erlande-Brandenburg, p 101

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Erlande-Brandenburg, p 78

- ↑ Maitland, Dark Ages, § xxii

- ↑ Edm. Bishop, Origin of the Primer, (Early English Text Society, original series, 109.), p. xxx

- ↑ Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods.

- ↑ Woods, p 33

- ↑ Woods, p 34-35

- ↑ Gimpel, p 68; cited by Woods, p 35

- ↑ Erlande-Brandenburg, p 116-117

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Woods, p 37

- ↑ R. W. Vernon, G. McDonnell and A. Schmidt, 'An integrated geophysical and analytical appraisal of early iron-working: three case studies' Historical Metallurgy 31(2) (1998), 72-5 79

- ↑ An agreement (immediately after that) concerning the 'smythes' with the Earl of Rutland in 1541 refers to blooms. H. R. Schubert, History of the British iron and steel industry from c. 450 BC to AD 1775 (Routledge, London 1957), 395-7.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance (Trappists): Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 Abbey of Our Lady of the Holy Trinity: Brief History

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Cistercian Order of the Strict Observance (Trappists): Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Michael Jackson's Beer Hunter - Chastity, poverty and a pint

- ↑ The Cistercian Abbey of Our Lady of Spring Bank

- ↑ Rob Baedeker (2008-03-24). "Good Works: Monks build multimillion-dollar business and give the money away". San Francisco Chronicle.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

References

- Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain (1995). The Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages. Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0500300526 ISBN 978-0500300527.

- Clarke, Howard B.; Dent, Sarah; Johnson, Ruth (2002). Dublinia: The Story of Medieval Dublin. Dublin: O'Brien. ISBN 0862787858.

- Dykes, D.W. (1980). Alan Sorrell: Early Wales Re-created. National Museum of Wales. ISBN 0 7200 02281.

- Gimpel, Jean, The Medieval Machine: The Industrial Revolution of the Middle Ages (New York, Penguin, 1976)

- Logan, F. Donald, A History of the Church in the Middle Ages.

- Tobin, Stephen. The Cistercians: Monks and Monasteries in Europe. The Herbert Press, LTD 1995. ISBN 1-871569-80-X.

- Watt, John, The Church in Medieval Ireland. University College Dublin Press; Second Revised Edition (May 1998). ISBN 190062110X. ISBN 978-1900621106.

- Woods, Thomas, How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization (2005), ISBN 0-89526-038-7.

External links

- Newadvent.org, Catholic Encyclopedia

- Cistercian Information, Certosa di Firenze (some in English)

- A Benedictine Index - the Cistercians

- Charta Caritatis (English)

- Carta Caritatis (Latin)

- Institute of Cistercian Studies

Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists)

Order of Cistercians Common Observance

- International Cistercian site

- Website of oldest surviving Cistercian monastery in Austria, partly in English