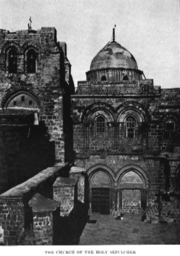

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Latin: Sanctum Sepulchrum), also called the Church of the Resurrection, (Greek: Ναός της Αναστάσεως, Naos tis Anastaseos; Arabic: كنيسة القيامة, Kanīsat al-Qiyāma; Armenian: Սուրբ Հարություն Surp Harutyun) by Eastern Christians, is a Christian church within the walled Old City of Jerusalem.

The site is venerated by most Christians as Golgotha,[1] (the Hill of Calvary), where the New Testament says that Jesus was crucified,[2] and is said to also contain the place where Jesus was buried (the sepulchre). The church has been an important pilgrimage destination since at least the 4th century, as the purported site of the death and resurrection of Jesus. Today it also serves as the headquarters of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem, while control of the building is shared between several Christian churches and secular entities in complicated arrangements essentially unchanged for centuries.

Contents |

History

Construction

Eusebius describes in his Life of Constantine[3] how the site of the Holy Sepulchre, originally a site of veneration for the Christian community in Jerusalem, had been covered with earth, upon which a temple of Venus had been built. Although Eusebius does not say as much, this was probably done as part of Hadrian's reconstruction of Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina in 135, following the destruction of the Jewish Revolt of 70 and Bar Kokhba's revolt of 132–135. Emperor Constantine I ordered in about 325/326 that the site be uncovered, and instructed Saint Macarius, Bishop of Jerusalem, to build a church on the site. Pilgrim of Bordeaux reports in 333: "There, at present, by the command of the Emperor Constantine, has been built a basilica, that is to say, a church of wondrous beauty" (page 594). Socrates Scholasticus (born c. 380), in his Ecclesiastical History, gives a full description of the discovery[4] (that was repeated later by Sozomen and by Theodoret) that emphasizes the role played in the excavations and construction by Constantine's mother Saint Helena, to whom is also credited the rediscovery of the True Cross. Helena had been directed by her son to build churches upon sites which commemorated the life of Jesus Christ, so the Church of the Holy Sepulchre commemorated the death and resurrection of Jesus, just as the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (also founded by Constantine and Helena) commemorated his birth.

Constantine's church was built beside the excavated hill of the Crucifixion, and was actually three connected churches built over the three different holy sites, including a great basilica (the Martyrium visited by the nun Egeria in the 380s), an enclosed colonnaded atrium (the Triportico) built around the traditional Rock of Calvary, and a rotunda, called the Anastasis ("Resurrection"), which contained the remains of the cave that Helena and Macarius had identified as the burial site of Jesus. The surrounding rock was cut away, and the Tomb was encased in a structure called the Kουβούκλιον (Kouvouklion; Greek for small compartment) or Edicule (Latin: aediculum, small building) in the center of the rotunda. The dome of the rotunda was completed by the end of the 4th century.

Each year, the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates the anniversary of the consecration of the Church of the Resurrection (Holy Sepulchre) on September 13 (for those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, September 13 currently falls on September 26 of the modern Gregorian Calendar).

Damage and destruction

This building was damaged by fire in 614 when the Persians under Khosrau II invaded Jerusalem and captured the Cross. In 630, Emperor Heraclius marched triumphantly into Jerusalem and restored the True Cross to the rebuilt Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Under the Muslims it remained a Christian church. The early Muslim rulers protected the city's Christian sites, prohibiting their destruction and their use as living quarters. In 966 the doors and roof were burnt during a riot.

On October 18, 1009, under the so-called "mad" Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, orders for the complete destruction of the Church were carried out. It is believed that Al-Hakim "was aggrieved by the scale of the Easter pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which was caused specially by the annual miracle of the Holy Fire within the Sepulchre. The measures against the church were part of a more general campaign against Christian places of worship in Palestine and Egypt, which involved a great deal of other damage: Adhemar of Chabannes recorded that the church of St George at Lydda 'with many other churches of the saints' had been attacked, and the 'basilica of the Lord's Sepulchre destroyed down to the ground'. ...The Christian writer Yahya ibn Sa'id reported that everything was razed 'except those parts which were impossible to destroy or would have been too difficult to carry away'."[5] The Church's foundations were hacked down to bedrock. The Edicule and the east and west walls and the roof of the cut-rock tomb it encased were destroyed or damaged (contemporary accounts vary), but the north and south walls were likely protected by rubble from further damage. The "mighty pillars resisted destruction up to the height of the gallery pavement, and are now effectively the only remnant of the fourth-century buildings."[5] Some minor repairs were done to the section believed to be the tomb of Jesus almost immediately after 1009, but a true attempt at restoration would have to wait for decades.[5]

European reaction was of shock and dismay, with far-reaching and intense consequences. For example, Clunaic monk Raoul Glaber blamed the Jews, with the result that Jews were expelled from Limoges and other French towns. Ultimately, this destruction provided an impetus to the later Crusades.[6]

Reconstruction

In wide ranging negotiations between the Fatimids and the Byzantine Empire in 1027-8 an agreement was reached whereby the new Caliph Ali az-Zahir (Al-Hakim's son) allowed the Emperor Constantine VIII to finance the rebuilding and redecoration of the Church (thereby acknowledging his patronage over it).[7] As a concession, the mosque in Constantinople was re-opened and sermons were to be pronounced in az-Zahir's name.[7] Muslim sources say a by-product of the agreement was the recanting of Islam by many Christians who had been forced to convert under Al-Hakim's persecutions.[7] In addition the Byzantines, while releasing 5,000 Muslim prisoners, made demands for the restoration of other churches destroyed by Al-Hakim and the re-establishment of a Patriarch in Jerusalem.[7] Contemporary sources credit the emperor with spending vast sums in an effort to restore the Church of the Holy Sepulchre after this agreement was made.[7] The rebuilding project continued under stringent conditions imposed by the caliphate, and was completed in 1048 by Constantine IX Monomachos and Patriarch Nicephorus of Constantinople.[8] Despite the Byzantines spending vast sums on the project, "a total replacement was far beyond available resources. The new construction was concentrated on the rotunda and its surrounding buildings: the great basilica remained in ruins."[5] The rebuilt church site consisted of "a court open to the sky, with five small chapels attached to it."[9] The chapels were "to the east of the court of resurrection, where the wall of the great church had been. They commemorated scenes from the passion, such as the location of the prison of Christ and of his flagellation, and presumably were so placed because of the difficulties for free movement among shrines in the streets of the city. The dedication of these chapels indicates the importance of the pilgrims' devotion to the suffering of Christ. They have been described as 'a sort of Via Dolorosa in miniature'... since little or no rebuilding took place on the site of the great basilica. Western pilgrims to Jerusalem during the eleventh century found much of the sacred site in ruins."[5] Control of Jerusalem, and thereby the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, continued to change hands several times between the Fatimids and the Seljuk Turks (loyal to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad) until the arrival of the Crusaders in 1099.[10]

Crusader and later periods

Many historians still maintain that the main concern of Pope Urban II, when calling for the First Crusade, was the threat to Constantinople from the Turkish invasion of Asia Minor in response to the appeal of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Still, historians agree that the fate of Jerusalem and thereby the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was of concern if not the immediate goal of papal policy in 1095. The idea of taking Jerusalem gained more focus as the Crusade was underway. The rebuilt church site was taken from the Fatimids (who had recently taken it from the Abassids) by the knights of the First Crusade on 15 July 1099.[5]

The First Crusade was envisioned as an armed pilgrimage, and no crusader could consider his journey complete unless he had prayed as a pilgrim at the Holy Sepulchre. Crusader Prince Godfrey of Bouillon, who became the first crusader monarch of Jerusalem, decided not to use the title "king" during his lifetime, and declared himself Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri, "Protector (or Defender) of the Holy Sepulchre."

The chronicler William of Tyre reports on the renovation of the Church in the mid-12th century. The crusaders began to refurnish the church in a Romanesque style and added a bell tower. These renovations unified the small chapels on the site and were completed during the reign of Queen Melisende in 1149, placing all the Holy places under one roof for the first time. The church became the seat of the first Latin Patriarchs, and was also the site of the kingdom's scriptorium. The church was lost to Saladin, along with the rest of the city, in 1187, although the treaty established after the Third Crusade allowed for Christian pilgrims to visit the site. Emperor Frederick II regained the city and the church by treaty in the 13th century, while he himself was under a ban of excommunication, leading to the curious result of the holiest church in Christianity being laid under interdict. Both city and church were captured by the Khwarezmians in 1244.

The Franciscan friars renovated it further in 1555, as it had been neglected despite increased numbers of pilgrims. A fire severely damaged the structure again in 1808, causing the dome of the Rotunda to collapse and smashing the Edicule's exterior decoration. The Rotunda and the Edicule's exterior were rebuilt in 1809–1810 by architect Komminos of Mytilene in the then current Ottoman Baroque style. The fire did not reach the interior of the Edicule, and the marble decoration of the Tomb dates mainly to the 1555 restoration. The current dome dates from 1870. Extensive modern renovations began in 1959, including a restoration of the dome from 1994–1997. The cladding of red marble applied to the Edicule by Komminos has deteriorated badly and is detaching from the underlying structure; since 1947 it has been held in place with an exterior scaffolding of iron girders installed by the British Mandate. No plans have been agreed upon for its renovation.

Status quo

Since the renovation of 1555, control of the church oscillated between the Franciscans and the Orthodox, depending on which community could obtain a favorable firman from the Sublime Porte at a particular time, often through outright bribery, and violent clashes were not uncommon. In 1767, weary of the squabbling, the Porte issued a firman that divided the church among the claimants. This was confirmed in 1852 with another firman that made the arrangement permanent, establishing a status quo of territorial division among the communities.

The primary custodians are the Eastern Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Roman Catholic Churches, with the Greek Orthodox Church having the lion's share. In the 19th century, the Coptic Orthodox, the Ethiopian Orthodox and the Syriac Orthodox acquired lesser responsibilities, which include shrines and other structures within and around the building. Times and places of worship for each community are strictly regulated in common areas.

Establishment of the status quo did not halt the violence, which continues to break out every so often even in modern times. On a hot summer day in 2002, the Coptic monk who is stationed on the roof to express Coptic claims to the Ethiopian territory there moved his chair from its agreed spot into the shade. This was interpreted as a hostile move by the Ethiopians, and eleven were hospitalized after the resulting fracas.[11]

In another incident in 2004 during Orthodox celebrations of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, a door to the Franciscan chapel was left open. This was taken as a sign of disrespect by the Orthodox and a fistfight broke out. Some people were arrested, but no one was seriously injured.[12]

On Palm Sunday, in April 2008, a brawl broke out due to a Greek monk being ejected from the building by a rival faction. Police were called to the scene but were also attacked by the enraged brawlers.[13] A clash erupted between Armenian and Greek monks on Sunday 9 November 2008, during celebrations for the Feast of the Holy Cross.[14][15]

Under the status quo, no part of what is designated as common territory may be so much as rearranged without consent from all communities. This often leads to the neglect of badly needed repairs when the communities cannot come to an agreement among themselves about the final shape of a project. Just such a disagreement has delayed the renovation of the edicule, where the need is now dire, but also where any change in the structure might result in a change to the status quo disagreeable to one or more of the communities.

A less grave sign of this state of affairs is located on a window ledge over the church's entrance. Someone placed a wooden ladder there sometime before 1852, when the status quo defined both the doors and the window ledges as common ground. The ladder remains there to this day, in almost exactly the same position. It can be seen to occupy the ledge in century-old photographs and engravings.

None of the communities controls the main entrance. In 1192, Saladin assigned responsibility for it to two neighboring Muslim families. The Joudeh were entrusted with the key, and the Nusseibeh, who had been the custodians of the church since the days of Caliph Omar in 637, retained the position of keeping the door. This arrangement has persisted into modern times. Twice each day, a Joudeh family member brings the key to the door, which is locked and unlocked by a Nusseibeh.

Modern arrangement of the church

The entrance to the church is through a single door in the south transept. This narrow way of access to such a large structure has proven to be hazardous at times. For example, when a fire broke out in 1840, dozens of pilgrims were trampled to death. In 1999 the communities agreed to install a new exit door in the church, but there was never any report of this door being completed.

- Just inside the entrance is The Stone of Anointing, believed to be the spot where Jesus' body was prepared for burial by Joseph of Arimathea. There is a difference of opinion as to whether it is the 13th Station of the Cross, which others identify as the lowering of Jesus from the cross and locate between the 11th and 12th station up on Calvary. The lamps that hang over the stone are contributed by Armenians, Copts, Greeks and Latins.

- To the left, or west, is The Rotunda of the Anastasis beneath the larger of the church's two domes, in the center of which is The Edicule of the Holy Sepulchre itself. The Edicule has two rooms. The first one holds The Angel's Stone, a fragment of the stone believed to have sealed the tomb after Jesus' burial. The second one is the tomb itself. Under the status quo the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Armenian Apostolic Churches all have rights to the interior of the tomb, and all three communities celebrate the Divine Liturgy or Holy Mass there daily. It is also used for other ceremonies on special occasions, such as the Holy Saturday ceremony of the Holy Fire celebrated by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem. To its rear, within a chapel constructed of iron latticework upon a stone base semicircular in plan, lies the altar used by the Coptic Orthodox.

- Beyond that to the rear of the Rotunda is a very rough hewn chapel believed to be the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea in which the Syriac Orthodox celebrate their Liturgy on Sundays. To the right of the sepulchre on the southeastern side of the Rotunda is the Chapel of the Apparition which is reserved for Roman Catholic use.

- On the east side opposite the Rotunda is the Crusader structure housing the main altar of the Church, today the Greek Orthodox catholicon. The second, smaller dome sits directly over the center of the transept crossing of the choir where the compas, an omphalos once thought to be the center of the world (associated to the site of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection), is situated. East of this is a large iconostasis demarcating the Greek Orthodox sanctuary before which is set the Patriarchal throne and a throne for visiting episcopal celebrants.

- On the south side of the altar via the ambulatory is a stairway climbing to Calvary (Golgotha), believed to be the site of Jesus' crucifixion and the most lavishly decorated part of the church. The main altar there belongs to the Greek Orthodox, which contains The Rock of Calvary (12th Station of the Cross). The rock can be seen under glass on both sides of the altar, and beneath the altar there is a hole said to be the place where the cross was raised. The Roman Catholics (Franciscans) have an altar to the side, The Chapel of the Nailing of the Cross (11th Station of the Cross). On the left of the altar, towards the Eastern Orthodox chapel, there is a statue of Mary, believed to be working wonders (the 13th Station of the Cross, where Jesus' body was removed from the cross and given to his family).

- Beneath the Calvary and the two chapels there, on the main floor, there is The Chapel of Adam. According to tradition, Jesus was crucified over the place where Adam's skull was buried. The Rock of Calvary is seen cracked through a window on the altar wall, the crack being said to be caused by the earthquake that occurred when Jesus died on the cross.

- From The Chapel of Adam, a door leads to The Treasure Room, underneath the Roman Catholic Chapel on the Calvary, holding holy relics and the True Cross. The room is usually closed, and opened on special occasions.

- Further to the east in the ambulatory are three chapels (from south to north): Greek Chapel of the Derision, Armenian Chapel of Division of Robes and Greek Chapel of St. Longinus.

- Between the first two chapels are stairs descending to The Chapel of St. Helena, belonging to the Armenians. From there, another set of 42 stairs leads down to the Roman Catholic Chapel of the Invention of the Holy Cross, believed to be the place where the True Cross was found.

- In the north-east side of the complex there is The Prison of Christ, where it is believed Jesus was held.

Authenticity

As noted above, both Eusebius and Socrates Scholasticus record that the tomb of Jesus was originally a site of veneration for the Christian community in Jerusalem and its location remembered by that community even when the site was covered by Hadrian's temple. Eusebius in particular notes that the uncovering of the tomb "afforded to all who came to witness the sight, a clear and visible proof of the wonders of which that spot had once been the scene" (Life of Constantine, Chapter XXVIII).[16]

Archaeologist Martin Biddle of Oxford University has theorized that this "clear and visible proof" might have been a graffito to the effect of "This is the Tomb of Christ", scratched in the rock by Christian pilgrims before the construction of the Roman temple. Similar ancient graffiti are still visible in the Catacombs of Rome, indicating the tombs of especially venerated saints.

In the nineteenth century, a number of scholars disputed the identification of the Church with the actual site of Jesus's crucifixion and burial, on the basis that the Church was inside the city walls, while early accounts (e.g., Hebrews 13:12) described these events as outside the walls. On the morning after his arrival in Jerusalem, General Gordon selected a rock-cut tomb in a cultivated area outside the walls as a more likely site for the burial of Jesus. This site is usually referred to as the Garden Tomb to distinguish it from the Holy Sepulchre, and it is still a popular pilgrimage site for those (usually Protestants) who doubt the authenticity of the Anastasis and/or do not have permission to hold services in the Church itself.

However, it has since been determined that the site was indeed outside the city walls at the time of the crucifixion. The Jerusalem city walls were expanded by Herod Agrippa in 41–44, and only then enclosed the site of the Holy Sepulchre, at which time the surrounding garden mentioned in the Bible would have been built up as well. To quote the Israeli scholar Dan Bahat, former City Archaeologist of Jerusalem:

- "We may not be absolutely certain that the site of the Holy Sepulchre Church is the site of Jesus' burial, but we have no other site that can lay a claim nearly as weighty, and we really have no reason to reject the authenticity of the site."[17]

Image gallery

Influence

Since the 9th century, the construction of churches inspired in the Anastasis was extended across Europe.[18] One example is Santo Stefano in Bologna, Italy, an agglomeration of seven churches recreating shrines of Jerusalem.

Several churches and monasteries in Russia have been modelled on the Church of the Resurrection, some even reproducing other Holy Places for the benefit of pilgrims who could not travel to the Holy Land.

See also

- Tomb of Jesus

- Burial places of founders of world religions

- Order of the Holy Sepulchre, initiated by Godfrey of Bouillon

- Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Temple Church in London

- Early Christian art and architecture

- Constantine I and Christianity

- Art of the Crusades

- Garden Tomb

- Talpiot Tomb

- Church of the Nativity

References

- ↑ Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

- ↑ CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Holy Sepulchre

- ↑ NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine | Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- ↑ NPNF2-02. Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories | Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Colin Morris (2005). The Sepulchre of Christ and the Medieval West. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Bokenkotter, Thomas (2004). A Concise History of the Catholic Church. Doubleday. pp. 155. ISBN 0385505841.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Yaacov Lev (1991). State and Society in Fatimid Egypt. Brill.

- ↑ Frederick John Foakes-Jackson (1921). An Introduction to the History of Christianity. Macmillan Company.

- ↑ James Fergusson (1887). History of Architecture in All Countries. Dodd.

- ↑ Dore Gold (2007). The Fight for Jerusalem. Regnery Publishing.

- ↑ Christian History Corner: Divvying up the Most Sacred Place | Christianity Today | A Magazine of Evangelical Conviction

- ↑ Punch-up at tomb of Jesus | World news | The Guardian

- ↑ Armenian, Greek worshippers come to blows at Jesus' tomb - Haaretz - Israel News

- ↑ "Riot police called as monks clash in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre", Times Online (November 10, 2008). Retrieved on 2008-11-11.

- ↑ "Once again, monks come to blows at Church of Holy Sepulcher", The Associated Press (10/11/2008). Retrieved on 2008-11-11.

- ↑ NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine | Christian Classics Ethereal Library

- ↑ Bahat 1986

- ↑ Monastero di Santo Stefano: Basilica Santuario Santo Stefano: Storia, Bologna.

- "Divvying up the Most Sacred Place by Chris Armstrong, Christianity Today, Week of July 29, 2002, retrieved February 28, 2006.

- "Punch-up at tomb of Jesus" by Allyn Fisher-Ilan, The Guardian, September 28, 2004, retrieved February 28, 2006.

- "Video of brawl at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre" retrieved November 10, 2008.

Bibliography

- Coüasnon, Charles (1974). The church of the holy sepulchre. London.

- Corbo, Virgilio C. (1981). Il Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme. The holy sepulchre in Jerusalem. Aspetti archeologici dalle origini al periodo crociata, 3 Vol.. Jerusalem.

- Bahat, Dan (May/June), "Does the Holy Sepulchre church mark the burial of Jesus?", Biblical Archaeology Review 12 (3): 26–45

- Biddle, Martin (1999). The Tomb of Christ. Phoenix Mill: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1926-4.

- Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. London: Palestine Exploration Fund. 1994.

- Biddle, Martin; Avni, Gideon; Seligman, Jon & Winter, Tamar (text); Zabé, Michèl & Nalbandian, Garo (photos) (2000). The Church of the Holy Sepulchre. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-2282-6.

- Krüger, Jürgen (2000). Die Grabeskirche zu Jerusalem. Geschichte - Gestalt - Bedeutung. Regensburg.

- Gerhard Roese: 'The Reconstruction of the Tower of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem', published by Roese-Design, Darmstadt 2002, ISBN 3-00-009775-9

External links

General sites

- OrthodoxWiki (article)

- Sacred Destinations (article, interactive plan, photo gallery)

- History Channel site (article)

- The Reconstruction of the Tower of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (article)

- The Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (article, photos & video)

- Video of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (video)

Custodians

- Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land (Roman Catholic custodians)

- Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre (Greek Orthodox custodians)

- Joudeh family (Muslim custodian)

- Nuseibeh family (Muslim custodian)

Primary sources and scholarly articles

- Egeria's description in the 380s

- The Church of the Resurrection (EHR 7:417‑436, 669‑684)

Photo galleries

- Jerusalem Shots

- Holy Sepulchre Virtual Tour & Video (unique technology)

- Vadim Onishchenko

- Photo Gallery of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in 2007

- Virtual tour Full HD December 2007