Church of England

| Church of England | |

|---|---|

The Church of England logo since 1996. |

|

| Classification | Anglican (1534- ), Roman Catholic (597-1534) |

| Orientation | Mainline |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Associations | Anglican Communion, Porvoo Communion |

| Geographical Area | England, Isle of Man, Channel Islands |

| Development | |

| Separations | Congregationalism, Methodist Episcopal Church, other Methodist denominations |

| Statistics | |

| Members | 26 million[1] |

| Ministers | 20,259[2] |

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church[3] in England, the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the oldest among the communion's thirty-eight independent national churches.

The Church of England considers itself to be both Catholic and Reformed: [4]

- It is 'Catholic' in that it views itself as a part of the universal church of Christ in unbroken continuity with the early apostolic and later mediæval church. This is expressed in its strong emphasis on the teachings of the early Church Fathers, in particular as formalised in the Apostolic, Nicene and Athanasian creeds. [5]

- It is also 'Reformed' to the the extent that it has been influenced by some of the doctrinal principles of the 16th century Protestant Reformation. The more Reformed character finds expression in the Thirty-Nine Articles of religion, established as part of the settlement of religion under Queen Elizabeth I. The customs and liturgy of the Church of England, as expressed in the Book of Common Prayer, are based on older Catholic tradition but have been moderately influenced by Reformation liturgical and doctrinal principles.[6]

Contents |

History

According to tradition, Christianity arrived in Britain in the first or second century (probably via the tin trade route through Ireland and Iberia), and existed independently of the Church of Rome, as did many other Christian communities of that era.

The earliest unquestioned historical evidence of an organized Christian church in England is found in the writings of such early Christian fathers as Tertullian and Origen in the first years of the 3rd century, although the first Christian communities probably were established some decades earlier. Three English bishops, including Restitutus, are known to have been present at the Council of Arles in 314. Others attended the Council of Sardica in 347 and that of Ariminum in 360, and a number of references to the church in Roman Britain are found in the writings of 4th-century Christian fathers.

Britain was the home of Pelagius, who nearly defeated Augustine of Hippo's doctrine of original sin.

The Church of England traces its formal corporate history from the 597 Augustinian mission, stresses its continuity and identity with the primitive universal Western church, and notes the consolidation of its particular independent and national character in the post-Reformation events of Tudor England.

The Pope sent Saint Augustine from Rome to evangelise the Angles in 597. With the help of Christians already residing in Kent he established his church in Canterbury, the former capital of Kent (it is now Maidstone), and became the first in the series of Archbishops of Canterbury. A later archbishop, the Greek Theodore of Tarsus, also contributed to the organisation of English Christianity.

Simultaneously the Celtic church of St Columba continued to evangelise Scotland. The Celtic church of North Britain submitted in some sense to the 'authority' of Rome at the Synod of Whitby in 664. Over the next few centuries the Roman system introduced by Augustine gradually absorbed the pre-existing Celtic Christian churches.

The English church was under papal authority for nearly a thousand years, before separating from Rome in 1534 during the reign of King Henry VIII. A theological separation had been foreshadowed by various movements within the English church such as the Lollards, but the English Reformation gained political support when Henry VIII wanted an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne Boleyn. Under pressure from Catherine's nephew, the Emperor Charles V, Pope Clement VII refused the annulment. Eventually, Henry, although theologically a doctrinal Catholic, took the position of Supreme Head of the Church of England to ensure the annulment of his marriage. He was excommunicated by Pope Paul III[7].

Henry maintained a strong preference for the traditional Catholic practices and, during his reign, Protestant reformers were unable to make many changes to the practices of the Church of England. Indeed, this part of Henry's reign saw the trial for heresy of Protestants as well as Roman Catholics.

Under his son, Edward VI, more Protestant-influenced forms of worship were adopted. Under the leadership of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, a more radical reformation proceeded. A new pattern of worship was set out in the Book of common prayer. This was based on the older liturgy but influenced by Protestant principles. The confession of the new reformed church was set out in the Forty-two Articles (later revised to thirty-nine). The reformation however was cut short by the death of the king. Queen Mary I, who succeeded him, sought to return England again to the authority of the Pope and undo the reforms. Many leaders and common people were burnt for their refusal to recant of their reformed faith. These are known as the Marian martyrs and the persecution has led to her nickname of "Bloody Mary".

Mary also died young and so it was left to the new regime of her sister Elizabeth to resolve the direction of the church. The settlement under Elizabeth I (from 1558), known as the Elizabethan settlement, created what we know today as the Church of England. It produced a church which was moderately Reformed in doctrine, as expressed in the Thirty-nine Articles, which some characterise as moderate Calvinism. It also emphasised the continuity with the Catholic and Apostolic tradition of the Church Fathers and a liturgical style similar to that prior to its reformation. It was also an established church ( constituationally established by the state with the head of state as its supreme governor). The exact nature of the relationship between church and state would be a source of continued friction into the next century.

For the next century, through the reigns of James I, who ordered the creation of what became known as the King James Bible, and Charles I, and culminating in the English Civil War and the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, there were significant swings back and forth between two factions: the Puritans (and other radicals) who sought more far-reaching Protestant reforms, and the more conservative churchmen who aimed to keep closer to traditional beliefs and Catholic practices. The failure of political and ecclesiastical authorities to submit to Puritan demands for more extensive reform was one of the causes of open warfare. By Continental standards, the level of violence over religion was not high, but the casualties included a king, Charles I, and an Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Under the Commonwealth and then the Protectorate of England from 1649 to 1660, Anglicanism was disestablished and outlawed, and in its place, Presbyterian ecclesiology was introduced in place of the episcopate. In addition, the Articles were replaced with the Westminster Confession, and the Book of Common Prayer was replaced by the Directory of Public Worship. Despite this, about one quarter of English clergy refused to conform to this form of State Presbyterianism.

With the Restoration of Charles II, Anglicanism too was restored in a form not far removed from the Elizabethan version. One difference was that the ideal of encompassing all the people of England in one religious organisation, taken for granted by the Tudors, had to be abandoned. The religious landscape of England assumed its present form, with the Anglican established church occupying the middle ground, and Roman Catholics and those Puritans who dissented from the Anglican establishment, too strong to be suppressed altogether, having to continue their existence outside the National Church rather than controlling it.

Continuing official suspicion and legal restrictions continued well into the nineteenth century.

Doctrine and practice

- See also: Anglicanism and Anglican doctrine

Church of England doctrine can be summarised in its canon law as follows:

Canon A 5 Of the doctrine of the Church of England: "The doctrine of the Church of England is grounded in the Holy Scriptures, and in such teachings of the ancient Fathers and Councils of the Church as are agreeable to the said Scriptures. In particular such doctrine is to be found in the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, The Book of Common Prayer, and the Ordinal."[1]

As the Church of England bases its teachings on the Holy Scriptures, the ancient Catholic teachings of the Church Fathers and some of the doctrinal principles of the Protestant Reformation (as expressed in the 39 Articles, and other documents such as the Anglican Homilies), Anglicanism can therefore be described as 'Reformed Catholic' in character rather than Protestant. In practice, however, it is more mixed, with Anglicans who emphasise the Catholic tradition and others the Reformed tradition. There is also a long history of more liberal or latitudinarian views. These three 'parties' in the C of E are sometimes called high church or (Anglo-Catholic), low church (or Evangelical) and broad church (or Liberal). In terms of church government, unlike many of the Protestant denominations it has retained episcopal (bishop) leadership. The teachings of Richard Hooker, the 16th century divine, summarised the Anglican position well, affirming bishops as ancient, allowable and for the wellbeing of the church.[8]

In many people's eyes today the Church of England has, as one of its distinguishing marks, a breadth and "open-mindedness". This range of belief and practice includes those of the Anglo-Catholics, who emphasise liturgy and sacraments, to the far more preaching-centred and less ritual-based services of Evangelicals and gatherings of the Charismatics. But this "broad church" faces various contentious doctrinal questions raised by the development of modern society in particular relating to issues of gender roles and sexual expression. Thus there are disagreements over the ordination of women as priests (accepted in 1992 and begun in 1994), and about whether homosexual practice in the context of committed same-sex relationships is permissible. In July 2005 the divisions were once again apparent, as the General Synod voted to "set in train" the process of allowing the consecration of women as bishops; in February 2006 the synod voted overwhelmingly for "further exploration" of a scheme that would also allow parishes that did not want a woman bishop to opt for a man instead.[9] On July 7, 2008 the church's governing body voted to confirm the ordination of women as bishops.[10]

The church also has its own system of canon law, and judicial branch, known as the Ecclesiastical courts, which likewise form a part of the UK court system. Such courts have powers especially in relation to the care of churches and churchyards and the discipline of the clergy.

Ecumenical relations

Like many other Anglican churches, the Church of England has entered into full communion with the Old Catholics. In the late 20th century it also became a founding member of the new Porvoo Communion. The Church of England is also a full member of the Conference of European Churches.

Related churches

The Church of England's sister church in Ireland, the Church of Ireland, also went through the reformation in the sixteenth century. Unlike in England, the majority of the populace did not go along with this, preferring continued adherence to the Roman Catholic Church, but the Church of Ireland retained official established church status in Ireland until 1871. Under the Act of Union (Ireland) 1800, the Church of Ireland was united with the Church of England. This union was dissolved and the Irish church disestablished in 1871. To this day the Church of Ireland remains organised on an all-Ireland basis.

The Scottish Episcopal Church is the sister church in Scotland and is in full communion with it. It is much smaller than the Church of Scotland, which is recognised in law as the "national church" and has a Presbyterian system of government. The history of the Episcopal Church is complicated, involving alternating periods of official promotion and persecution: for a time, because of its association with Jacobitism, it had to operate sub rosa.

When the Episcopal Church in the U.S. became independent of the Church of England after the American War of Independence, the leadership of the Church of England did not believe itself legally able to consecrate new bishops without requiring of them the standard oath of loyalty to the crown. Consequently it was the non-juring bishops of the non-established Scottish Episcopal Church who consecrated the first American bishop, until new legislation allowed the Church of England to relax its policy.

The Church in Wales, previously a part of the Church of England, was disestablished in 1920 and at the same time became an independent member of the Anglican Communion.

Worship and liturgy

Book of Common Prayer

The Church of England's official book of liturgy as established in English Law is the Book of Common Prayer (BCP). This remains the touchstone of all Anglican liturgy. In addition to this, the General Synod has legislated for a modern liturgical book Common Worship, dating from 2000 which can be used as an alternative to the BCP. Like its predecessor, the 1980 Alternative Service Book, it differs from the Book of Common Prayer in providing a range of alternative services, some in more modern language, although it does include some BCP forms too, for example Order Two for Holy Communion. (This is a very slight revision of the prayer book service, altering a few words and allowing the insertion of some older liturgy such as the Agnus Dei) before communion. The Order One rite follows a pattern of more modern liturgical scholarship with more catholic elements.

Membership

In addition to England proper, the current jurisdiction of the Church of England extends to the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands, and a few parishes in Flintshire, Monmouthshire, and in Radnorshire, Wales (the present Church in Wales was an integral part of the Church of England until 1921). Expatriate congregations on the continent of Europe have become the Diocese of Gibraltar in Europe.

According to statistics "1.7 million people attend Church of England church and cathedral worship each month while around 1.2 million attend each week – on Sunday or during the week - and just over one million each Sunday."[2]

Structure

- See also: Anglican ministry

The Church of England article XIX (Of the Church) defines Church as follows:

"The visible Church of Christ is a congregation of faithful men, in the which the pure Word of God is preached, and the sacraments be duly ministered according to Christ's ordinance in all those things that of necessity are requisite to the same."[2]

Despite the complexities of the structure now to be outlined, at its heart, the Church of England views the local parish church as the basic unit and heartbeat of its life.

The British monarch, at present Queen Elizabeth II, has the constitutional title of "Supreme Governor of the Church of England". The Canons of the Church of England state, "We acknowledge that the Queen’s most excellent Majesty, acting according to the laws of the realm, is the highest power under God in this kingdom, and has supreme authority over all persons in all causes, as well ecclesiastical as civil." In practice this power is often exercised through Parliament and the Prime Minister.

The Church is then structured as follows (from the lowest level upwards):

- Parish, this is the most local level, often consisting of one church building and community, although nowadays many parishes are joining forces in a variety of ways for financial reasons. Larger parishes often have one or more chapels in addition to the parish church. The parish will be looked after by a parish priest who for various historical or legal reasons may bear any of the following titles: Vicar, Rector, Priest-in-Charge, Team Rector or Team Vicar. The first, second, and fourth of these may also be known as the Incumbent. The running of the parish is the joint responsibility of the incumbent and the Parochial Church Council (PCC), which consists of the parish clergy and elected representatives from the congregation.

- There are also a number of local churches which do not have a Parish. In urban areas there are a number of Proprietary Chapels (mostly built in the 19th century to cope with urbanisation and growth in population). Also in more recent years there are increasingly Church plants and Fresh expressions of Church, whereby new congregations are planted in a variety of locations (such as schools or pubs) in order to spread the Gospel of Christ in a fresh and non-traditional manner.

- Deanery, e.g., Lewisham, or Runnymede. This is the area for which a rural dean is responsible. It will consist of a number of parishes in a particular district. The rural dean will usually be the incumbent of one of the constituent parishes. The parishes each elect lay (that is non-ordained) representatives to the Deanery Synod. Deanery Synod members each have a vote in the election of representatives to the Diocesan Synod.

- Archdeaconry, e.g., Dorking. This is the area under the jurisdiction of an archdeacon. It will consist of a number of deaneries.

- Diocese, e.g., Diocese of Durham, Diocese of Guildford, Diocese of St Albans, more. This is the area under the jurisdiction of a diocesan bishop, e.g., the Bishops of Durham, Guildford and St Albans, and will have a cathedral. There may also be one or more assisting bishops, usually called Suffragan Bishops, within the diocese who assist the diocesan bishop in his ministry, e.g., in Guildford Diocese, the Bishop of Dorking. In some very large dioceses a legal measure has been enacted to create "Episcopal Areas", in which case the diocesan bishop will run one such Area himself, and will appoint an "Area Bishop" to run each of the other Areas as mini-dioceses; in such cases, the diocesan bishop legally delegates many of his powers to the area bishops. Dioceses with Episcopal Areas include London, Southwark, Chichester, and Lichfield. The bishops will work with an elected body of lay and ordained representatives, known as the Diocesan Synod, to run the diocese. A diocese is subdivided into a small number of archdeaconries.

- Province, e.g., York and Canterbury (these are the only two in the Church of England). This is the area under the jurisdiction of an archbishop, i.e. the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. Decision making within the province is the responsibility of the General Synod (see also above). A province is subdivided into many dioceses.

- Primacy, e.g., Church of England. This is the area under the jurisdiction of a primate, e.g., the Archbishop of Canterbury. A primacy may consist of one or several provinces.

- Peculiar A small number of churches are more closely associated with the Crown, and a very few with the Law, and are outside the usual church hierarchy, though conforming to the rite. These are outside the episcopal jurisdiction.

All rectors and vicars are appointed by patrons, who may be private individuals, corporate bodies such as cathedrals, colleges or trusts, or by the bishop or even appointed directly by the Crown. No clergy can be instituted and inducted into a parish without swearing the Oath of Allegiance to Her Majesty, and taking the Oath of Canonical Obedience "in all things lawful and honest" to the bishop. Usually they are instituted to the benefice by the bishop and then inducted by the archdeacon into the actual possession of the benefice property - church and parsonage. Curates are appointed by rectors and vicars, but if priests-in-charge then by the bishop after consultations with the patron. Cathedral clergy (normally a dean and a varying number of residentiary canons who constitute the cathedral chapter) are appointed either by the Crown, the bishop, or by the dean and chapter themselves. Clergy officiate in a diocese either because they hold office as beneficed clergy, or are licensed by the bishop when appointed (e.g. curates), or simply with permission.

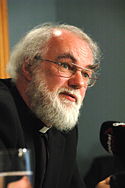

Primates

The most senior bishop of the Church of England is the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is the archbishop and primate of the southern province of England, the Province of Canterbury. He also has the status of Primate of All England and Metropolitan. He is also the focus of unity for the worldwide Anglican Communion of independent national or regional churches. The Most Reverend and Right Honourable Rowan Williams has served as Archbishop of Canterbury since 2002.

The second most senior bishop is the Archbishop of York, who is the archbishop and primate of the northern province of England, the Province of York. For historical reasons he is referred to as the Primate of England. The Most Reverend and Right Honourable John Sentamu has served as the Archbishop of York since 2005. The bishops of London, Durham and Winchester are ranked in the next three positions (third, fourth and fifth).

Diocesan bishops

The process of appointing diocesan bishops is complex, and is handled by a body called the Crown Nominations Committee, which submits names to the Prime Minister (acting on behalf of the Crown) for consideration.

Representative bodies

The Church of England has a legislative body, the General Synod. Synod can create two types of legislation, Measures and Canons. Measures have to be approved but cannot be amended by the UK Parliament before receiving the Royal Assent and becoming part of the law of England.[11] Canons require Royal Licence and Royal Assent, but form the law of the Church, rather than the law of the land.[12]

Another assembly is the Convocation of the English Clergy (older than the General Synod and its predecessor the Church Assembly). There are also Diocesan Synods and Deanery Synods.

Financial situation

The Church of England, although an established church, does not receive any direct government support. Donations comprise its largest source of income, though it also relies heavily on the income from its various historic endowments. As of 2005[update], the Church of England had estimated total outgoings of around £900 million.[13]

Historically, individual parishes both raised and spent the vast majority of the Church's funding, meaning that clergy pay depended on the wealth of the parish, and parish advowsons (the right to appoint clergy to particular parishes) could become extremely valuable gifts. Individual dioceses also held considerable assets: the Diocese of Durham possessed such vast wealth and temporal power that its Bishop became known as the 'Prince-Bishop'. Since the mid-19th century, however, the Church has made various moves to 'equalise' the situation, and clergy within each diocese now receive standard stipends paid from diocesan funds. Meanwhile, the Church moved the majority of its income-generating assets (which in the past included a great deal of land, but today mostly take the form of financial stocks and bonds) out of the hands of individual clergy and bishops to the care of a body called the Church Commissioners, which uses these funds to pay a range of non-parish expenses, including clergy pensions, and the expenses of cathedrals and bishops' houses. These funds amount to around £3.9 billion, and generate income of around £164 million each year (as of 2003[update]), around a fifth of the Church's overall income.[14]

The Church Commissioners give some of this money as 'grants' to local parishes; but the majority of the financial burden of church upkeep and the work of local parishes still rests with individual parish and diocese, which meet their requirements from donations. Direct donations to the church (not including legacies) come to around £460 million per year, while parish and diocese reserve funds generate another £100 million. Funds raised in individual parishes account for almost all of this money, and the majority of it remains in the parish which raises it, meaning that the resources available to parishes still vary enormously, according to the level of donations they can raise.

Most parishes give a portion of their money, however, to the diocese as a 'quota' or 'parish share'. While this is not a compulsory payment, dioceses strongly encourage and rely on it being paid; it is usually only withheld by parishes either if they are unable to find the funds or as a specific act of protest. As well as paying central diocesan expenses such as the running of diocesan offices, these diocesan funds also provide clergy pay and housing expenses (which total around £260 million per year across all dioceses), meaning that clergy living conditions no longer depend on parish-specific fundraising.

Although asset-rich, the Church of England has to look after and maintain its thousands of churches nationwide — the lion's share of England's built heritage.[15] As current congregation numbers stand at relatively low levels and as maintenance bills increase as the buildings grow older, many of these churches cannot maintain economic self-sufficiency; but their historical and architectural importance make it difficult to sell them. In recent years, cathedrals and other famous churches have met some of their maintenance costs with grants from organisations such as English Heritage; but the church congregation and local fundraisers must foot the bill entirely in the case of most small parish churches.[16] (The government, however, does provide some assistance in the form of tax breaks, for example a 100% VAT refund for renovations to religious buildings.)

In addition to consecrated buildings, the Church also controls numerous ancillary buildings attached to or associated with churches, including a good deal of clergy housing. As well as vicarages and rectories, this housing includes residences (often called 'palaces') for each of the Church's 114 bishops. In some cases, this name seems entirely apt; buildings such as Archbishop of Canterbury's Lambeth Palace in London and Old Palace at Canterbury have truly palatial dimensions, while the Bishop of Durham's Auckland Castle has 50 rooms, a banqueting hall and 30 acres (120,000 m²) of parkland. However, many bishops have found the older palaces inappropriate for today's lifestyles, and some bishops' 'palaces' are ordinary four bedroomed houses. Many dioceses which have retained large palaces now employ part of the space as administrative offices, while the bishops and their families live in a small apartment within the palace; and in recent years some dioceses have managed to put their palaces' excess space and grandeur to profitable use as conference centres. All three of the more grand bishop's palaces mentioned above — Lambeth Palace, Canterbury Old Palace and Auckland Castle — serve as offices for church administration, conference venues, and only in a lesser degree the personal residence of a bishop. The size of the bishops' households has shrunk dramatically and their budgets for entertaining and staff form a tiny fraction of their pre-twentieth-century levels.

References

- ↑ Factfile: Anglican Church around the world BBC Factfile. Accessed 2006-06-22.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Latest Church of England statistics (15/09/2006)

- ↑ "The History of the Church of England". The Archbishops' Council of the Church of England. Retrieved on 2006-05-24.

- ↑ http://www.cofe.anglican.org/faith/anglican/

- ↑ http://www.cofe.anglican.org/about/churchlawlegis/canons/church.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cofe.anglican.org/about/churchlawlegis/canons/church.pdf

- ↑ HistoryMole: King Henry VIII (1491-1547)

- ↑ Hooker's ecclesiastical polity: http://www.churchsociety.org/issues_new/history/hooker/iss_history_hooker_carter-position.asp

- ↑ Church votes overwhelmingly for compromise on women bishops - news from ekklesia | Ekklesia

- ↑ "Church will ordain women bishops", BBC News (July 7, 2008). Retrieved on 2008-07-07.

- ↑ "Summary of Church Assembly and General Synod Measures". Church of England website. Archbishops' council of the Church of England (November 2007).

- ↑ "General Synod". Church of England website. Archbishops' council of the Church of England.

- ↑ outgoings

- ↑ funds

- ↑ "The Church of Englnd's built heritage". Church of England website. Archbishops' Council of the Church of England (2004). "The Church of England has some 16,000 church buildings, in 13,000 parishes covering the whole of England, as well as 43 cathedrals. Together they form a unique collection of buildings; between 12,000 and 13,000 churches are listed, i.e. are recognised by the Government as being of exceptional historic or architectural importance, and about 45% of all Grade I buildings in England are churches. Though first and foremost a place of worship, churches are also often the oldest building in a settlement still in continual use. Even in industrial or twentieth-century settlements, they are a focus. Many churches – and cathedrals particularly - are the largest, most architecturally complex, most archaeologically sensitive, and most visited building in their village, town or city."

- ↑ local fundraisers

See also

- Appointment of Church of England bishops

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- British monarchy

- Church of England parish church

- Historical development of Church of England dioceses

- List of Church of England bishops

- List of Church of England dioceses

- Religion in the United Kingdom

- Ritualism

- Shrinking the footprint

- Church of England Newspaper

External links

- Church of England website

- Find a Church in the Church of England ("A Church Near You")

- The Society for Sacramental Mission

- Historical resources on the Church of England

- Church of England history in the West Indies

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||