Niqqud

Letters in black, niqqud in red, cantillation in blue

| Hebrew alphabet |

|---|

| א ב ג ד ה ו |

| ז ח ט י כך |

| ל מם נן ס ע פף |

| צץ ק ר ש ת |

| History · Transliteration Niqqud · Dagesh · Gematria Cantillation · Numeration |

In Hebrew orthography, niqqud or nikkud (Hebrew: נִקּוּד, Biblical נְקֻדּוֹת, Standard nekudot Tiberian nəquddôṯ ; "dots") is the system of diacritical signs used to represent vowels or distinguish between alternative pronunciations of consonants of the Hebrew alphabet. Several systems for representing Hebrew vowels were developed in the Early Middle Ages. The most widespread system, and the only one still used to a significant degree today, was created by the Masoretes of Tiberias in the second half of the first millennium in the Land of Israel (see Masoretic Text, Tiberian Hebrew).

Niqqud marks are small compared to consonants, so they can be added without retranscribing texts whose writers did not anticipate them.

Among those who do not speak Hebrew, niqqud are the sometimes unnamed focus of controversy regarding the interpretation of those written with the Tetragrammaton—written as יְהֹוָה in Hebrew. The interpretation affects discussion of the authentic ancient pronunciation of the name whose other conventional English forms are "Jehovah" and "Yahweh".

Contents |

Short table

Israeli Hebrew has five vowel phonemes—/i/, /e/, /a/, /o/, and /u/—but many more written symbols for them. Niqqud denote the following vowels.

| Name | Symbol | Unicode | Israeli Hebrew | Keyboard input | Hebrew | Alternate Names |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Transliteration | English Example |

Letter | Key | |||||

| Hiriq | U+05B4 | [i] | i | seek | 4 | חִירִיק | ‒ | ||

| Tzeire | U+05B5 | [ɛ] and [ɛi] | e and ei | men | 5 | צֵירֵי or צֵירֶה | ‒ | ||

| Segol | U+05B6 | [ɛ], ([ɛi] with succeeding yod) |

e, (ei with succeeding yod) |

men | 6 | סֶגוֹל | ‒ | ||

| Patakh | U+05B7 | [a] | a | far | 7 | פַּתָּח | ‒ | ||

| Kamatz | U+05B8 | [a], (or [ɔ]) | a, (or o) | far | 8 | קָמָץ | ‒ | ||

| Sin dot (left) | U+05C2 | [s] | s | sour | 9 | שִׂי״ן | ‒ | ||

| Shin dot (right) | U+05C1 | [ʃ] | sh | shop | 0 | שִׁי״ן | ‒ | ||

| Holam | U+05B9 | [ɔ] | o | bore | - | חוֹלָם | ‒ | ||

| Dagesh or Mappiq

Shuruk |

U+05BC | N/A | N/A | N/A | = | דָּגֵשׁ or מַפִּיק | ‒ | ||

| U+05BC | [u] | u | cool | שׁוּרוּק | ‒ | ||||

| Kubutz | U+05BB | [u] | u | cool | \ | קֻבּוּץ | ‒ | ||

| Below: Two vertical dots underneath the letter (called sh'va) make the vowel very short. | |||||||||

| Sh'va | U+05B0 | [ɛ] or [-] | apostrophe, e, or nothing |

silent | ~ | שְׁוָא | ‒ | ||

| Reduced Segol | U+05B1 | [ɛ] | e | men | 1 | חֲטַף סֶגוֹל | Hataf Segol | ||

| Reduced Patakh | U+05B2 | [a] | a | far | 2 | חֲטַף פַּתָּח | Hataf Patakh | ||

| Reduced Kamatz | U+05B3 | [ɔ] | o | bore | 3 | חֲטַף קָמָץ | Hataf Kamatz | ||

Note Ⅰ: The symbol "O" represents whatever Hebrew letter is used.

Note Ⅱ: The letter "ש" is used since it can only be represented by that letter..

Note Ⅲ: The dagesh, mappiq, and shuruk are different, however, they look the same and are inputted in the same manner. Also, they are represented by the same Unicode character.

Note Ⅳ: The letter "ו" is used since it can only be represented by that letter.

Vowel comparison table

| Vowel Comparison Table | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vowel length | IPA | Transliteration | English example |

|||||

| Long | Short | Very short | ||||||

| [2] | [1] | [a] | a | far | ||||

| [3] | [2][3] | [1] | [ɔ] | o | dog | |||

| [4] | [4] | n/a | [u] | u | you | |||

| n/a | [i] | i | ski | |||||

| [1] | [ɛ] | e | let | |||||

Notes:

- [1] : By adding two vertical dots (sh'va) ְ the short vowel is made very short.

- [2] : The short o and long a have the same niqqud.

- [3] : The short o is usually promoted to a long o (waw with mappiq) in Israeli writing for the sake of disambiguation.

- [4] : The short u is usually promoted to a long u (yod with mappiq) in Israeli writing for the sake of disambiguation.

Long table

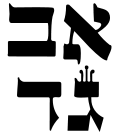

This table uses the consonants ב ,ח or ש, where appropriate, to demonstrate where the niqqud is placed in relation to the consonant it is pronounced after. Any other consonants shown are actually part of the vowel. Note that there is some variation among different traditions in exactly how some vowel points are pronounced. The table below shows how most Israelis would pronounce them, but the classic Ashkenazi pronunciation, for example, differs in several respects.

- This demonstration is known to work in Internet Explorer and Mozilla browsers in at least some circumstances, but in most other Windows browsers the niqqud do not properly combine with the consonants. This is because, currently, the Windows text display engine does not combine the niqqud automatically. Except as noted, the vowel pointings should appear directly beneath the consonants and the accompanying "vowel letter" consonants for the mālê (long) forms appear after.

| Symbol | Type | Common name | Alternate names | Scientific name | Hebrew | IPA | Transliteration | Comments | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| בְ | Israeli | Sh'va | sheva | šəva | שְׁוָא | [ɛ] or Ø | ə, e, ', or nothing |

In modern Hebrew, shva is pronounced either /e/ or Ø, regardless of its traditional classification as shva naḥ (שווא נח) or shva na (שווא נע), see following table for examples:

|

|||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | šəwâ | שְׁוָא | [ə] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| חֱ | Israeli | Reduced segol | hataf segol | ḥataf seggol | חֲטַף סֶגּוֹל | [ɛ] | e | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥăṭep̄ səḡôl | חֲטֶף סְגוֹל | [ɛ] | ĕ | ‒ | ||||||||||||||||||

| חֲ | Israeli | Reduced patach | hataf patah | ḥataf pátaḥ | חֲטַף פַּתַח | [a] | a | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥăṭep̄ páṯaḥ | חֲטֶף פַּתַח | ă | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| חֳ | Israeli | Reduced kamatz | hataf kamats | ḥataf qamaẓ | חֲטַף קָמָץ | [ɔ] | o | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥăṭep̄ qāmeṣ | חֲטֶף קָמֶץ | [ɔ] | ŏ | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בִ | Israeli | Hiriq | hiriq | ḥiriq | חִירִיק | [i] | i | Usually promoted to Hiriq Malei in Israeli writing for the sake of disambiguation. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥîreq | חִירֶק | [i] or [iː]) | i or í | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בִי | Israeli | Hiriq malei | hiriq yod | ḥiriq male | חִירִיק מָלֵא | [i] | i | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥîreq mālê | חִירֶק מָלֵא | [iː] | î | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בֵ | Israeli | Zeire | tsere, tzeirei | ẓere | צֵירֵי | [ɛ] | e | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ṣērê | צֵרֵי | [eː] | ē | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בֵי, בֵה, בֵא | Israeli | Zeire malei | tsere yod, tzeirei yod | ẓere male | צֵירֵי מָלֵא | [ɛ] | e | More commonly ei (IPA [ei]). | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ṣērê mālê | צֵרֵי מָלֵא | [eː] | ê | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בֶ | Israeli | Segol | segol | seggol | סֶגּוֹל | [ɛ] | e | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | səḡôl | סְגוֹל | [ɛ] or [ɛː] | e or é | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בֶי, בֶה, בֶא | Israeli | Segol malei | segol yod | seggol male | סֶגּוֹל מָלֵא | [ɛ] | e | With succeeding yod, it is more commonly ei (IPA [ei]) | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | səḡôl mālê | סְגוֹל מָלֵא | [ɛː] | ệ | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בַ | Israeli | Patach | patah | pátaḥ | פַּתַח | [a] | a | A patach on a letter ח at the end of a word is sounded before the letter, and not behind. Thus, נֹחַ (Noah) is pronounced /no-ax/. This only occurs at the ends of words and only with patach and ח, ע, and הּ (that is, ה with a dot (mappiq) in it). This is sometimes called a patach g'nuvah, or "stolen" patach (more formally, "furtive patach"), since the sound "steals" an imaginary epenthetic consonant to make the extra syllable. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | páṯaḥ | פַּתַח | [a] or [aː] | a or á | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בַה, בַא | Israeli | Patach malei | patah yod | pátaḥ male | פַּתַח מָלֵא | [a] | a | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | páṯaḥ mālê | פַּתַח מָלֵא | [aː] | ậ | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בָ | Israeli | Kamatz gadol | kamats | qamaẓ gadol | קָמַץ גָּדוֹל | [a] | a | — | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | qāmeṣ gāḏôl | קָמֶץ גָּדוֹל | [ɔː] | ā | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בָה, בָא | Israeli | Kamatz malei | kamats he | qamaẓ male | קָמַץ מָלֵא | [a] | a | comm | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | qāmeṣ mālê | קָמֶץ מָלֵא | [ɔː] | â | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בָ | Israeli | Kamatz katan | kamats hatuf | qamaẓ qatan | קָמַץ קָטָן | [ɔ] | o | Usually promoted to Holam Malei in Israeli writing for the sake of disambiguation. Also, not to be confused with Hataf Kamatz. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | qāmeṣ qāṭān | קָמֶץ קָטָן | [ɔ] | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| בֹ | Israeli | Holam | holam | ḥolam | חוֹלָם | [ɔ] | o | Usually promoted to Holam Malei in Israeli writing for the sake of disambiguation. The holam is written above the consonant on the left corner, or slightly to the left of (i.e., after) it at the top. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥōlem | חֹלֶם | [oː] | ō | comm | ||||||||||||||||||

| בוֹ, בֹה, בֹא | Israeli | Holam malei | holam male | ḥolam male | חוֹלַם מָלֵא | [ɔ] | o | The holam is written in the normal position relative to the main consonant (above and slightly to the left), which places it directly over the vav. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | ḥōlem mālê | חֹלֶם מָלֵא | [oː] | ô | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בֻ | Israeli | Kubutz | kubuts | qubbuẓ | קֻבּוּץ | [u] | u | Usually promoted to Shuruk in Israeli writing for the sake of disambiguation. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | [u/] or [uː/] | u or ú | |||||||||||||||||||||

| בוּ, בוּה, בוּא | Israeli | Shuruk | shuruk | šuruq | שׁוּרוּק | [u] | u | The shuruk is written after the main consonant, because it is essentially a vav with a piercing; the piercing is written identically to a dagesh (see below). | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | šûreq | שׁוּרֶק | [uː] | û | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| בּ | Israeli | Dagesh | dagesh | dageš | דָּגֵשׁ | varied | varied | Though Standard Hebrew indicates doubled consonants in transliteration, such doubling (gemination)—but not consonant plosiveness—is almost universally ignored in Israeli Hebrew. For most consonants the dagesh is written within the consonant, near the middle if possible, but the exact position varies from letter to letter; some letters do not have an open area in the middle, and in these cases it is written usually beside the letter, as with yod. A dagesh used to signify a plosive variant (of letters בגדכפת), but not gemination is known as a dagesh qal, whereas that which geminates a letter is known as a dagesh hazaq. The guttural consonants (אהחע) and resh (ר) do not take a dagesh, although the letter he (ה) may appear with a mappiq (which is written the same way as dagesh) at the end of a word to indicate that the letter is not only being used to signify a vowel, but is consonantal. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | dāḡēš | דָּגֵשׁ | Not actually a vowel. It hardens or doubles the consonant it modifies. The resulting form can still take a niqqud vowel. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| בֿ | Israeli | Rafe | rafe | Not used in Hebrew. Still occasionally seen in Yiddish (actually more often as the spelling becomes more standardized, embracing YIVO rules) to distinguish פּ /p/ from פֿ /f/ (note that this letter is always pronounced [f] when in the final position, with the exception of loanwords—שׁוֹףּ—, foreign names—פִילִיףּ— and some slang—חָרַףּ). Some ancient manuscripts have a dagesh or a rafe on nearly every letter. It is also used to indicate that a letter like ה or א is silent. In the particularly strange case of the Ten Commandments, which have two different traditions for their Cantillations which many texts write together, there are cases of a single letter with both a dagesh and a rafe, if it is hard in one reading and soft in the other. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | Niqqud, but not a vowel. Used as an "anti-dagesh", to show that a בגדכפת letter is soft and not hard, or (sometimes) that a consonant is single and not double, or that a letter like ה or א is completely silent | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| שׁ | Israeli | Shin dot | shin dot | šin dot | שׁי"ן | [ʃ] | š/sh | Niqqud, but not a vowel (unless the letter before the shin has a holam, in which case the holam merges with the shin dot). The dot for shin is written over the right (first) branch of the letter. It is usually written as sh. | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| שׂ | Israeli | Sin dot | sin dot | śin dot | שׂי"ן | [s] | ś/s | Niqqud, but not a vowel (unless the sin has a holam, in which case the sin dot and holam merge). The dot for sin is written over the left (third) branch of the letter | |||||||||||||||

| Tiberian | Some linguistic evidence indicates that it was originally IPA [ɬ], though poetry and acrostics show that it has been pronounced /s/ since quite ancient times). | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Niqqud and the keyboard

For the Hebrew letters there is a standardized Hebrew keyboard. But when it comes to niqqud, different computer systems and programs provide for adding the signs in different ways.

Using the Hebrew keyboard layout in Microsoft Windows the typist can enter niqqud by pressing CapsLock, putting the cursor after the consonant letter and then pressing Shift and one of the following keys:

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

- [1] The letter "O" represents whatever Hebrew letter is used.

- [2] For sin-dot and shin-dot, the letter "ש" (sin/shin) is used since they can only be used with that letter.

- [3] The dagesh, mappiq, and shuruk are different; however, they look the same and (hence) are input the same way (all 3 of them.)

- [4] For shuruk, the letter "ו" (vav) is used since it can only be used with that letter.

Rules for writing without niqqud

-

For more details on this topic, see Ktiv male.

In modern Israeli orthography niqqud is seldom used, except in specialised texts such as dictionaries, poetry, or texts for children or for new immigrants. For purposes of disambiguation, a system of spelling-without-niqqud, known in Hebrew as ktiv male (Hebrew: כתיב מלא), literally "full spelling" has developed. This was formally standardised in the Rules for Spelling without Niqqud (כללי הכתיב חסר הניקוד) enacted by the Academy of the Hebrew Language in 1996.[1]

Disputes among Protestant Christians

Protestant literalists who believe that the Hebrew text of the Old Testament is the inspired Word of God are divided on the question of whether or not the vowel points should be considered an inspired part of the Old Testament. In 1624, Louis Cappel, a French Huguenot scholar at Saumur, published a work in which he concluded that the vowel points were a later addition to the biblical text and that the vowel points were added not earlier than the fifth century AD. This assertion was hotly contested by Swiss theologian Johannes Buxtorf in 1648. Brian Walton's 1657 polyglot bible followed Cappel in revising the vowel points. In 1675, the 2nd and 3rd canons of the so-called Helvetic Consensus of the Swiss Reformed Church confirmed Buxtorf's view as orthodox and affirmed that the vowel points were inspired.

See also

- The Arabic equivalent, harakat.

- Q're perpetuum

- Dagesh

- Hebrew spelling

References

External links

- A free online course to learn the Hebrew Vowel System

- Rules for Spelling without Niqqud - a simplified version of the Rules, published on the Academy of the Hebrew Language website.

Important: There is currently a serious bug affecting niqqud in all Wikimedia projects. See Wikipedia:Niqqud for a discussion of the problem in English, and click the language link in the sidebar for an extensive analysis of the problem in Hebrew.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||