Cherokee

| Cherokee ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ |

|---|

|

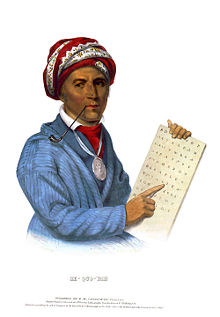

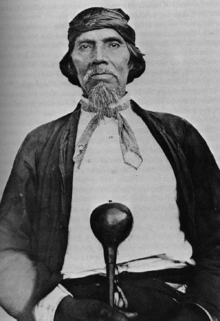

| Top: Sequoyah, 1835; bottom: Swimmer, 1888. |

| Total population |

|

320,000+ |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Federally Enrolled members: Cherokee Nation (f): United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, Oklahoma (f): Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, North Carolina (f): Cherokee Nation of Mexico, Coahuila (f): (f) = federally recognized |

| Languages |

| English, Cherokee |

| Religion |

| Christianity (Southern Baptist and Methodist), Traditional Ah-ni-yv-wi-ya, other small Christian groups. |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Tuscarora, Iroquoians, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole. |

The Cherokee (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯ, a-ni-yv-wi-ya, in the Cherokee language) are a people native to North America, who, at the time of European contact in the sixteenth century, inhabited what is now the Eastern and Southeastern United States. Most were forcibly moved westward to the Ozark Plateau in the 1830s. They are one of the tribes referred to as the Five Civilized Tribes. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, they are the largest of the 563 federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States. [1]

The Cherokee refer to themselves as Tsa-la-gi (ᏣᎳᎩ, pronounced "Zah la gee" or "Sa lah gi" in the eastern Giduwa dialect or pronouced "ja-la-gee" in western dialect) or A-ni-yv-wi-ya (pronounced "ah knee yuh wee yaw" (western) or "Ah nee yuhn wi yah" (Eastern dialect), literal translation: "Principal People").

The characteristics of the Cherokee people were described in the writings of William Bartram in his journey through the Cherokee lands in 1776;

"The Cherokee…are tall, erect and moderately robust; their limbs well shaped, so as generally to form a perfect human figure; their features regular, and countenance open, dignified, and placid, yet the forehead and brow are so formed as to strike you instantly with heroism and bravery; the eye, though rather small, yet active and full of fire, the iris always black, and the nose commonly inclining to the aquiline. Their countenance and actions exhibit an air of magnanimity, superiority, and independence. Their complexion is a reddish brown or copper colour; their hair, long, lank, coarse, and black as a raven, and reflecting the like lustre at different exposures to the light. The women of the Cherokees are tall, slender, erect and of a delicate frame; their features formed with perfect symmetry; the countenance cheerful and friendly; and they move with a becoming grace and dignity" (R. C. Pritchard, Researches into the Physical History of Mankind (Volume V, 1847), p.403-4)

The Cherokee Nation and United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians have headquarters in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is located at Cherokee, North Carolina. All three are federally recognized.

Contents |

History

Prehistoric & Protohistoric Periods

Unlike most other Indians in the American southeast at the start of the historic era, the Cherokee spoke an Iroquoian language. Since the Great Lakes region was the core of Iroquoian languages, it is theorized that the Cherokee migrated south from that region. Linguistic analysis shows a relatively large difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages, suggesting a split in the distant past.[2] Glottochronology studies suggest the split occurred between about 1,500 and 1,800 B.C.[3] The ancient settlement of Keetoowah or giduwa (Cherokee:), on the Tuckasegee River near present-day Bryson City, North Carolina, is frequently cited as the original Cherokee City in the Southeast.[2]

In describing the history of Indians living in the interior of the American southeast, scholars use the term prehistory for the time before 1540, when Spanish under Hernando de Soto first passed through Cherokee country. De Soto's expedition visited many of the same Georgia and Tennessee villages later identified as Cherokee, but found them to be ruled by the Coosa chiefdom at that time. To the northeast, the Chiska inhabited all the country surrounding Whitetop Mountain where Tennessee, Virginia and North Carolina meet, while a Chalaque nation was recorded as living around the Keowee River where North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia meet (Mooney). The Spanish occupied the area around Joara with forts in 1567-68, but these proved unable to withstand native assaults, and were soon destroyed.

Following these failed attempts at colonization, the historic record is silent for about a century. The term protohistory is sometimes used for this period. What happened during this time is uncertain, but the territory of the former Coosa and Chiska nations seems to have become Cherokee, and their members either were assimilated by the Cherokee nation, or altered the names of their tribes and moved elsewhere. Since historic documentation is generally lacking, Cherokee prehistory and protohistory have been studied via oral tradition, linguistic analysis, and archaeology.

Heckewelder in 1819 recounted a Lenape tradition that the regions south of the Ohio River had once been occupied by a former nation called Alligewi or Talligewi, which some theories assume derives from Tsalagi, while others have connected them with early references to a Cherokee legend of a 'moon-eyed' race had who had been in their land before them.

Iroquois called the Cherokee Oyata’ge'ronoñ', "inhabitants of the cave country" (Hewitt). Allegheny Mountain's Mingo called the Upper-most Cherokee, Uyata'kéá', the "cave" kind, implying steep hollow (Lachler, McElwain). [4]The word "Cherokee" may have originally been derived from the Choctaw trade language word "Cha-la-kee", which means "those who live in the mountains" – or (also Choctaw) "Chi-luk-ik-bi" meaning "those who live in the cave country".[5]

17th Century

According to James Mooney, the English first had contact with the Cherokee in 1654. Around this time, the Powhatan were threatened by a tribe they knew as the Rickahockans or Rechahecrians who invaded from the west and settled near the falls of the James River. However, while some authors have linked these with the Cherokee, others deduce they were a Siouan tribe, since they appear in company with Monacan and Nahyssan groups.

One of the earliest English accounts comes from the expedition of James Needham and Gabriel Arthur, sent in 1673 by fur-trader Abraham Wood from Fort Henry (modern Petersburg, Virginia) to the Overhill Cherokee country. Wood hoped to forge a direct trading connection with the Cherokee in order to bypass the Occaneechi Indians who were serving as middlemen on the Trading Path. The two Virginians did make contact with the Cherokee, although Needham was killed on the return journey and Arthur was almost killed. By the late seventeenth century, traders from both Virginia and South Carolina were making regular journeys to Cherokee lands, but few wrote about their experiences.

Much of the early trading contact period has only been pieced together by colonial laws and lawsuits involving traders. The trade was mainly deerskins, raw material for the booming European leather industry, in exchange for European technology "trade goods" such as iron and steel tools (kettles, knives, etc), firearms, gunpowder, and ammunition. In 1705, these traders complained that their business had been lost and replaced by Indian slave trade instigated by Governor Moore of South Carolina. Moore had commissioned people to "set upon, assault, kill, destroy, and take captive as many Indians as possible". These captives would be sold and the profits split with the Governor.[6] Although selling alcohol to Indians was made illegal by colonial governments at an early date, rum, and later whiskey, were a common item of trade.[7]

During the early historic era, Europeans wrote of several Cherokee town groups, usually using the terms Lower, Middle, and Overhill towns to designate the towns, from the piedmont across the Allegheny Mountains.

The Lower towns were situated on the headwater streams of the Savannah River, mainly in present-day western South Carolina and northeastern Georgia. Keowee was one of the chief towns.

The Middle towns were located in present western North Carolina, on the headwater streams of the Tennessee River, such as the Little Tennessee River, Hiwassee River, and French Broad River. Among several chief towns was Nikwasi.

The Overhill towns were located across the higher mountains in present eastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia. Principal towns included Chota and Great Tellico. These terms were created and used by Europeans to describe their changing geopolitical relationship with the Cherokee.[2]

18th century

Of the southeastern Indian confederacies of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, etc), the Cherokee were one of the most populous and powerful, and were relatively isolated by their hilly and mountainous homeland. A relatively small-scale trading system was established with Virginia in the late seventeenth century. A much stronger and important trade relationship with the colony of South Carolina, based in Charles Town, began in the 1690s and overshadowed the Virginia relationship by the 1700s.[8]

Around 1710, the Cherokee together with the Chickasaw forced their enemies, the Shawnee, north of the Ohio[9].

Although there was some trading contact, the Cherokee remained relatively unaffected by the presence of European colonies in America until the Tuscarora War and its aftermath. In 1711, the Tuscarora began attacking colonists in North Carolina after diplomatic attempts to address various grievances failed. The governor of North Carolina asked South Carolina for military aid. Before the war was over several years later, South Carolina had mustered and sent two armies against the Tuscarora. The ranks of both armies were made up mostly of Indians, with Yamasee troops especially. The first army, under the command of John Barnwell, campaigned in North Carolina in 1712. By the end of the year, a fragile peace had been established, and the army dispersed. No Cherokee were involved in the first army. Hostilities between the Tuscarora and North Carolina broke out soon after, and in late 1712 to early 1713, a second army from South Carolina fought the Tuscarora. This army consisted of about 100 British and over 700 Indian soldiers. As with the first army, the second depended heavily on the Yamasee and Catawba. This time, however, hundreds of Cherokee also joined the army. The army's campaign ended after a major Tuscarora defeat at Hancock's Fort. All told, over 1,000 Tuscarora and allied Indians were killed or captured. Those captured were mainly sold into the Indian slave trade. Although the second army from South Carolina disbanded soon after the battle, the Tuscarora War continued for several years. Some previously neutral Tuscarora turned hostile, and the Iroquois confederacy entered the dispute. In the end a large number of Tuscarora moved north to live among the Iroquois.

The Tuscarora War altered the geopolitical context of colonial America in several ways, including an increased Iroquois interest in the south. For the many southeastern Indians involved, it was the first time so many had collaborated in a military campaign and seen how different the various English colonies were. As a result, the war helped to bind the Indians of the entire region together. It enhanced Indian networks of communication and trade. The Cherokee became much more closely integrated with the region's various Indians and Europeans. The Tuscarora War marked the beginning of an English-Cherokee relationship that, despite breaking down on occasion, remained strong for much of the 18th century.

The Tuscarora War also marks the rise of Cherokee military power, demonstrated in the 1714 attack and destruction of the Yuchi town of Chestowee (in today's southeastern Tennessee). The English traders Alexander Long and Eleazer Wiggan instigated the attack through various deceptions and promises, although there had been a pre-existing conflict between the Cherokee and Yuchi. The traders' plot was based in the Cherokee town of Euphase (Great Hiwassee), and mainly involved Cherokee from that town. In May 1714, the Cherokee destroyed the Yuchi town of Chestowee. Inhabitants not killed or captured fled to the Creek or the Savannah River Yuchi. Long and Wiggan told the Cherokee that the South Carolina government wished for and approved this attack, which was not true. The governor of South Carolina, having heard of the plot, sent a messenger to tell the Cherokee not to continue the attack on Yuchi. The messenger arrived too late to save Chestowee. The Cherokee attack on the Yuchi ended with Chestowee, but it was enough to catch the attention of every Indian tribe and European colony in the region. Thus, around 1715, the Cherokee emerged as a major regional power.[8]

In 1715, just as the Tuscarora War was winding down, the Yamasee War broke out. Numerous Indian tribes launched attacks on South Carolina. The Cherokee participated in some of the attacks, but were divided on what course to take. After South Carolina's militia succeeded in driving off the Yamasee and Catawba, the Cherokee's position became strategically pivotal. Both South Carolina and the Lower Creek tried to gain Cherokee support. Some Cherokee favored an alliance with South Carolina and war on the Creek, while others favored the opposite. The impasse was resolved in January 1716, when a delegation of Creek leaders was murdered at the Cherokee town of Tugaloo. Subsequently, the Cherokee launched attacks against the Creek, but in 1717, peace treaties between South Carolina and the Creek were finalized, undermining the Cherokee's commitment to war. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades,[10], coming to a head at the 1755 Battle of Taliwa in present-day Georgia, where 500 Cherokee decisively defeated a force of nearly 1000 Creeks, forcing the Creeks to abandon their town on Nottely Creek.

In 1721, the Cherokee made their first land cession to the British, selling the South Carolina colony a small strip of land between the Saluda, Santee and Edisto rivers. In 1730, at Nikwasi, Chief Moytoy II of Tellico was chosen as "Emperor" by the Elector Chiefs of the principal Cherokee towns. He unified the Cherokee Nation from a society of interrelated city-states in the early 18th century with the aid of an unofficial English envoy, Sir Alexander Cuming. Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain as the Cherokee protector. Seven prominent Cherokee, including Attacullaculla, traveled with Sir Alexander Cuming back to England. The Cherokee delegation stayed in London for four months. The visit culminated in a formal treaty of alliance between the British and Cherokee, the 1730 Treaty of Whitehall. While the journey to London and the treaty were important factors in future British-Cherokee relations, the title of Cherokee Emperor did not carry much clout among the Cherokee and passed out of Moytoy's direct avuncular lineage.

The unification of the Cherokee nation was essentially ceremonial, with political authority remaining town-based for decades afterward. In addition, Sir Alexander Cuming's aspirations to play an important role in Cherokee affairs failed.[11] In 1735 the Cherokee were estimated to have sixty-four towns and villages and 6000 fighting men. In 1738 - 39 smallpox was introduced to the country via sailors and slaves from the slave trade. An epidemic broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity, and killed nearly half their population within a year. Hundreds of other Cherokee committed suicide due to disfigurement from the disease.

Upon hearing reports that the French were planning to build forts in Cherokee territory, the British hastened to build forts of their own, completing Fort Prince George near Keowee (in South Carolina) among the Lower Towns, and in 1756, Fort Loudoun near Chota. In this year the Cherokee gave their assistance to the British in the French and Indian War; however, serious misunderstandings between the two allies arose quickly, and in 1760, the Cherokee besieged both forts, eventually capturing Fort Loudoun. The British retaliated by destroying 15 communities in 1761, and peace treaties ending hostilities were signed by the end of the year. A Royal Proclamation of 1763 from King George III forbade British settlements west of the Appalachian crest, affording some temporary protection from encroachment to the Cherokee, but it proved difficult to enforce[12].

The Cherokee and Chickasaw continued to war intermittently with the Shawnee along the Cumberland River for many years; the Shawnee allied with the Lenape, who remained at war with the Cherokee until 1768.

Beginning around the time of the American Revolutionary War, divisions over continued accommodation of encroachments by white settlers, despite repeated violations of previous treaties, caused some Cherokee to begin leaving the Cherokee Nation. Many of these dissidents became known as the Chickamauga. Led by Chief Dragging Canoe, the Chickamauga made alliances with the Shawnee, and engaged in raids against colonial settlements. Some of these early dissidents moved by 1800 across the Mississippi River to areas that would later become the states of Arkansas and Missouri. Their settlements were established on the St. Francis and the White Rivers by 1800. The Cherokee fought a final battle with the Shawnee in Tazewell County, Virginia in 1786[13].

Historians

Much of what is known about pre 19th century Cherokee history, culture, and society comes from the papers of American writer John Howard Payne. The Payne papers describe the memory Cherokee elders had of a traditional societal structure in which a "white" organization of elders represented the seven clans. This group, which was hereditary and described as priestly, was responsible for religious activities such as healing, purification, and prayer. A second group of younger men, the "red" organization, was responsible for warfare. However, warfare was considered a polluting activity which required the purification of the priestly class before participants could reintegrate in normal village life.

This hierarchy had faded by the time of the Cherokee removal in 1838. The reasons for the change have been debated and may include: a revolt by the Cherokee against the abuses of the priestly class, the massive smallpox epidemic of the late 1730s, and the incorporation of Christian ideas, which transformed Cherokee religion by the end of the eighteenth century.[14]

Ethnographer James Mooney, who studied the Cherokee in the late 1880s, traced the decline of the former hierarchy to the revolt.[15] By the time of Mooney, the structure of Cherokee religious practitioners was more informal and based more on individual knowledge and ability than upon heredity. In addition, separation of the Eastern Cherokee, who had not participated in the removal and remained in the mountains of western North Carolina, further complicated the traditional hierarchies.[14]

Another major source of early cultural history comes from the materials written in Cherokee by the didanvwisgi (Cherokee:ᏗᏓᏅᏫᏍᎩ), or Cherokee medicine men, after the creation of the Cherokee syllabary by Sequoya in the 1820s. These materials were initially only used by the didanvwisgi and were considered extremely powerful.[14] Later, these were widely adopted by the Cherokee people.

19th century

In 1815—after the War of 1812 in which Cherokees fought on behalf of both the British and American armies— the U.S. Government established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas. The reservation boundaries extended from north of the Arkansas River to the southern bank of the White River. Cherokee bands who lived in Arkansas were: The Bowl, Sequoyah, Spring Frog and The Dutch. Another band of Cherokee lived in southeast Missouri, western Kentucky and Tennessee in frontier settlements and in European majority communities around the Mississippi River.

John Ross was an important figure in the history of the Cherokee tribe. His father emigrated from Scotland prior to the Revolutionary War; his mother was a quarter-blood Cherokee woman whose father was also from Scotland. John Ross began his public career in 1809. The Cherokee Nation was founded in 1820, with elected public officials. John Ross became the chief of the tribe in 1828 and remained the chief until his death in 1866.

Trail of Tears

Cherokees were displaced from their ancestral lands in northern Georgia and the Carolinas in a period of rapidly expanding white population. Some of the rapid expansion was due to a gold rush around Dahlonega, Georgia in the 1830s. Various official reasons for the removal were given. One official argument was that the Cherokee were not efficiently using their land and the land should be given to white farmers. Others suggest that President Andrew Jackson's reasons for this removal policy were humanitarian. Jackson said that the policy was an effort to prevent the Cherokee from facing the fate of "the Mohegan, the Narragansett, and the Delaware".[16] However there is ample evidence that the Cherokee were adapting modern farming techniques, and a modern analysis shows that the area was in general in a state of economic surplus.[17]

Despite a Supreme Court ruling in their favor, many in the Cherokee Nation were forcibly relocated West, a migration known as the Trail of Tears or in Cherokee Nunna Daul Tsunny (Cherokee:The Trail Where They Cried) and by another term Tlo Va Sa (Cherokee:The Tragedy). This took place during the Indian Removal Act of 1830, although as of 1883, the Cherokee were the last large southern Indian tribe to be removed. Even so, the harsh treatment the Cherokee received at the hands of white settlers caused some to enroll to emigrate west.[18] As the Cherokee were slaveholders, they took enslaved African Americans with them west of the Mississippi.

Samuel Carter, author of Cherokee Sunset, writes: "Then… there came the reign of terror. From the jagged-walled stockades the troops fanned out across the Nation, invading every hamlet, every cabin, rooting out the inhabitants at bayonet point. The Cherokees hardly had time to realize what was happening as they were prodded like so many sheep toward the concentration camps, threatened with knives and pistols, beaten with rifle butts if they resisted."[19]

Another Cherokee, this time a child called Samuel Cloud turned 9 years old on the Trail of Tears. Samuel's written memory is retold by his great-great grandson, Micheal Rutledge, in his paper Forgiveness in the Age of Forgetfulness. Micheal, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is a law student at Arizona State University:

I know what it is to hate. I hate those white soldiers who took us from our home. I hate the soldiers who make us keep walking through the snow and ice toward this new home that none of us ever wanted. I hate the people who killed my father and mother. I hate the white people who lined the roads in their woollen clothes that kept them warm, watching us pass. None of those white people are here to say they are sorry that I am alone. None of them care about me or my people. All they ever saw was the colour of our skin. All I see is the colour of theirs and I hate them.[3]

Ridge opposition

Among the Cherokee, John Ross led the battle to halt their removal. Ross's position was in opposition to a group known as the "Ridge Party" or the "Treaty Party". This was in reference to the Treaty of New Echota, which exchanged Cherokee land for land in the west and its principle signers John Ridge and his father Major Ridge.

On June 22, 1839, the prominent signers of the Treaty of New Echota were executed, including Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot by Cherokee extremists.

In the early 1860s, John Ridge's son, novelist John Rollin Ridge, led a group of delegates to Washington, D.C. in a failed attempt to gain federal recognition for a Cherokee faction that was opposed to the leadership of Chief John Ross.[20]

Separation

In 1848, a group of Cherokee set out on an expedition to California, looking for new settlement lands. The expedition followed the Arkansas River upstream to the Rocky Mountains in present-day Colorado, then followed the base of the mountains northward into present-day Wyoming, before turning westward. The route become known as the Cherokee Trail or the Rocky Mountain Trail. Starting from Fort Smith, Arkansas, it extended northward to the Canadian border near Cut Back, Montana.

The group, which undertook gold prospecting in California, returned along the same route the following year, noticing placer gold deposits in tributaries of the South Platte. The discovery went unnoticed for a decade but eventually became one of the primary sources of the Pike's Peak Gold Rush of 1859 and other gold rushes across the western U.S. in the 1860s.

Not all of the eastern Cherokees were removed on the Trail of Tears. William Holland Thomas, a white store owner and state legislator from Jackson County, North Carolina, helped over 600 Cherokee from Qualla Town (the site of modern-day Cherokee, North Carolina) obtain North Carolina citizenship. As citizens, they were exempt from forced removal to the west. In addition, over 400 other Cherokee hid from Federal troops in the remote Snowbird Mountains of neighboring Graham County, North Carolina, under the leadership of Tsali (ᏣᎵ)[21] (the subject of the outdoor drama Unto These Hills held in Cherokee, North Carolina). Together, these groups were the basis for what is now known as the Eastern Band of Cherokees.

- See also: Cherokee in the American Civil War

Out of gratitude to Thomas, these Western North Carolina Cherokees served in the American Civil War as part of Thomas's Legion. Thomas's Legion consisted of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The legion mustered approximately 2,000 men of both Cherokee and white origin, fighting on behalf of the Confederacy, primarily in Virginia, where their battle record was outstanding.[22] Thomas's Legion was the last Confederate unit in the eastern theater of the war to surrender after capturing Waynesville, North Carolina on May 9, 1865. They agreed to cease hostilities on the condition of being allowed to retain their arms for hunting. This, together with Stand Watie the chief of the Southern Cherokee Nation's surrender of western forces on July 23, 1865, gave the Cherokees the distinction of being the very last Confederates to capitulate in both theaters of the Civil War.

As in southern states, the end of the Civil War brought freedom to enslaved African Americans. By an 1866 treaty with the US government, the Cherokee agreed to grant tribal citizenship to freedmen who had been held by them as slaves. Both before and after the Civil War, some Cherokee intermarried or had relationships with African Americans, just as they had with whites. Many Cherokee Freedmen were active politically within the tribe.

In Oklahoma, the Dawes Act of 1887 broke up the tribal land base. Under the Curtis Act of 1898, Cherokee courts and governmental systems were abolished by the U.S. Federal Government. In 1893 the Southern Cherokee Nation was recognized as an Indian tribe in Kentucky.

20th century

These and other acts were designed to end tribal sovereignty and to pave the way for Oklahoma Statehood in 1907. The Federal government appointed chiefs to the Cherokee Nation, often just long enough to sign a treaty. In reaction to this, the Cherokee Nation recognized that it needed leadership and a general convention was convened in 1938 to elect a Chief. They choose J. B. Milam as principal chief, and, as a goodwill gesture, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt confirmed the election in 1941.

W. W. Keeler was appointed chief in 1949. Because the federal government had adopted a self-determination policy, the Cherokee Nation was able to rebuild its government and W. W. Keeler was elected chief by the people, via a Congressional Act signed by President Richard Nixon. Keeler, who was also the President of Phillips Petroleum, was succeeded by Ross Swimmer and then Wilma Mankiller.

The 1997 Cherokee Constitutional Crisis

The Cherokee Nation was seriously destabilized in May 1997 in what was variously described as either a nationalist "uprising" or an "anti-constitutional coup" instigated by Joe Byrd, their Principal Chief. Elected in 1995, Byrd became locked in a battle of strength with the judicial branch of the Cherokee tribe. The crisis came to a dramatic head on March 22, 1997, when Joe Byrd, Principal Chief, stated in a press conference that he would decide which orders of the Cherokee Nation’s Supreme Court were lawful and which were not.

A simmering crisis continued over Byrd's creation of a private, armed paramilitary force. The crisis came to a head on June 20, 1997 when his private army illegally seized custody of the Cherokee Nation Courthouse from its legal caretakers and occupants, the Cherokee Nation Marshals, the Judicial Appeals Tribunal and its court clerks. They ousted the lawful occupants at gunpoint. Immediately the court demanded that the courthouse be returned to the judicial branch of the Cherokee Nation, but these requests were ignored by Byrd.[23]

The Federal authorities of the United States initially refused to intervene because of potential breach of tribal sovereignty. The State of Oklahoma recognized that Byrd's activities were breaches in state law. By August it sent in state troopers and specialist anti-terrorist teams. Byrd was required to attend a meeting in Washington DC with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, in which he was compelled to reopen the courts. He served the remainder of his elected term under supervision and remains a free man.

In 1999 Byrd lost the election for Principal Chief to Chad Smith.

The United Keetoowah Band

The United Keetoowah Band took a different track than the Cherokee Nation and received federal recognition after the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 . Members of the United Keetoowah Band are descended from the Old Settlers, Cherokees who moved west before the Removal. The tribe requires a quarter blood quantum for enrollment and UKB members must have at least one ancestor listed on the Final Dawes Roll of the Cherokee.

Customs and Ceremonies

Marriage

In Indian Territory, marriage between Cherokees and non-Cherokees was complicated on both sides. A white US man could legally marry a Cherokee woman by petitioning the federal court with approval of ten of her blood relatives.

Once married, the man became a member of the Cherokee tribe but had restricted rights; for instance, he could not hold any tribal office. He also remained a citizen of and under the laws of the United States. Many white men and Cherokee women chose instead simply to live together and call themselves married. This was known as "common law" marriage. After several years of cohabitation (requirements varied), the couple had the legal status of a formally married couple.

If a Cherokee man married a white woman, however, he was cut off from the tribe and no longer considered a member and citizen of its nation. Such marriages were much less frequent than between white men and Cherokee women.

Language and writing system

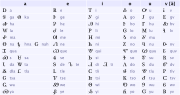

The Cherokee speak an Iroquoian language which is polysynthetic and is written in a syllabary invented by Sequoyah (ᏍᏏᏆᏱ). For years, many people wrote transliterated Cherokee on the Internet or used poorly intercompatible fonts to type out the syllabary. However, since the fairly recent addition of the Cherokee syllables to Unicode, the Cherokee language is experiencing a renaissance in its use on the Internet. As of January 2007, however, the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma still officially uses a non-unicode font for online documents, including online editions of the Cherokee Phoenix.

The Cherokee language does not contain any "r" based sounds. The word "Cherokee", when spoken in the language, is expressed as Tsa-la-gi (pronounced Jah-la-gee, or Je-la-gee) by native speakers, since these sounds most closely resemble the English language.

A southern Cherokee group did speak a local dialect with a trill consonant "r" sound. This "r" sound spoken in the dialect of the Elati, or Lower, Cherokee area – Georgia and Alabama – became extinct in the 19th century around the time of the Indian removal by the Trail of Tears; examples are Tsaragi or Tse-La-gee. The ancient Ani-kutani (ᎠᏂᎫᏔᏂ) dialect and Oklahoma dialects do not contain any 'r'-based sounds.

Because of the polysynthetic nature of the Cherokee Language, new and descriptive words in Cherokee are easily constructed to reflect or express modern concepts. Some good examples are di-ti-yo-hi-hi (Cherokee:ᏗᏘᏲᎯᎯ) which means "he argues repeatedly and on purpose with a purpose". This is the Cherokee word for attorney. Another example is di-da-ni-yi-s-gi (Cherokee:ᏗᏓᏂᏱᏍᎩ) which means "the final catcher" or "he catches them finally and conclusively". This is the Cherokee word for policeman.

Many words, however, have been borrowed from the English Language, such as gasoline which in Cherokee is ga-so-li-ne (Cherokee:ᎦᏐᎵᏁ). Many other words were borrowed from the languages of tribes who settled in Oklahoma in the early twentieth century. One example relates to a town in Oklahoma named "Nowata". The word nowata is a Delaware Indian word for "welcome" (more precisely the Delaware word is nu-wi-ta which can mean "welcome" or "friend" in the Delaware Language). The white settlers of the area used the name "nowata" for the township, and local Cherokees, being unaware the word had its origins in the Delaware Language, called the town a-ma-di-ka-ni-gv-na-gv-na (Cherokee:ᎠᎹᏗᎧᏂᎬᎾᎬᎾ) which means "the water is all gone from here", i.e. "no water".

Other examples of borrowed words are ka-wi (Cherokee:ᎧᏫ) for coffee and wa-tsi (Cherokee:ᏩᏥ) for watch (which led to u-ta-na wa-tsi (Cherokee:ᎤᏔᎾ ᏩᏥ) or "big watch" for clock).

Language drift

There are two main dialects in Cherokee spoken by modern speakers: the Giduwa or Kituhwa dialect (Eastern Band) and the Otali Dialect (also called the Overhill dialect) spoken in Oklahoma. The Otali dialect has drifted significantly from Sequoyah's Syllabary in the past 150 years, and many contracted and borrowed words have been adopted into the language. These noun and verb roots in Cherokee, however, can still be mapped to Sequoyah's Syllabary. In modern times, there are more than 85 syllables in use by modern Cherokee speakers. Modern Cherokee speakers who speak Otali employ 122 distinct syllables in Oklahoma.

Treaties, Government and Tribal Recognition

Treaties

- Treaty of Hopeville, 1785

- Changed the boundaries between the U.S. and Cherokee lands. Known as the "Talking Leaves Treaty" since the Cherokee claimed that when the treaties no longer suited the Americans, they would blow away like talking leaves.

- Treaty of Holston, 1791

- Established boundaries between the United States and the Cherokee Nation. Guaranteed by the United States that the lands of the Cherokee Nation have not been ceded to the United States.

- Treaty with the Cherokee, 1798

- The boundaries promised in the previous treaty had not been marked and white settlers had come in. Because of this, the Cherokee were told they would need to cede new lands as an "acknowledgement" of the protection of the United States. The U.S. would guarantee the Cherokee could keep the remainder of their land "forever".

- Treaties of Tellico, 1804 - 1806

- Roads had been built on the Cherokee land, and the U.S. added that its citizens should have "free and unmolested use and enjoyment of them", plus build a new road to deliver mail. Give the State of Tennessee some land for to convene an assembly. The U.S. wanted the Cherokee to become farmers. They began to send farming tools and spinning wheels as part of the treaties in place of some of the monies that were to be paid.

- Treaties of Washington, 1819 - 1835

- Resolution of Rattlesnake Springs, 1838

- "Resolved, by the Committee and Council of the Cherokee Nation in General Council assembled, that the whole Cherokee territory, as described in the first article of the treaty of 1819 between the United States and the Cherokee Nation, and, also, in the constitution of the Cherokee Nation, still remains the rightful and undoubted property of the said Cherokee Nation; and that all damages and losses, direct or indirect, resulting from the enforcement of the alleged stipulations of the pretended treaty of New Echota, are in justice and equity, chargeable to the account of the United States. The inherent sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation, together with the constitution, laws, and usages, of the same, are, and, by the authority aforesaid, hereby declared to be in full force and virtue, and shall continue so to be in perpetuity, subject to such modifications as the general welfare may render expedient. The Cherokee people do not intend that it shall be so construed as yielding or giving sanction or approval to the pretended treaty of 1835; nor as compromising, in any manner, their just claim against the United States hereafter, for a full and satisfactory indemnification for their country and for all individual losses and injuries."

- Treaties with the Republic of Texas, 1836 - 1844

- Generally overlooked as Cherokee treaties are three that are very important for Cherokee historians. These three consist of the Treaty of Bowles Village on February 23, 1836, granting nearly 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2) of east Texas land to the Texas Cherokees and twelve associated tribes. Violation of this treaty led to the Cherokee war of 1839 in which most Cherokees were driven north into the Choctaw Nation or who fled south into Mexico. Following this bloody episode, remaining Texas Cherokees under Chicken Trotter joined Mexican forces in a guerilla war that culminated with the invasion of San Antonio by Mexican General Adrian Woll. Cherokee and allied Indians saw action at the Battle of Salado Creek and against the Dawson regiment. Following this conflict, it was apparent that Mexico was not going to be able to provide the remaining Texas Cherokees with any stability or lands in Texas. This led to a push for peace by newly re-installed Texas President Sam Houston. The result was the Treaty of Birds Fort on September 29, 1843 which ended hostilities among several Texas tribes, including the Cherokees. The Treaty which was ratified by the Congress of the Republic of Texas, recognized the tribal status of the Texas Indians as distinct, including the Cherokees that would later become known as the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands-Mount Tabor Indian Community. This treaty, honored by the State of Texas following annexation has never been aboragated by the Congress of the United States and in theory is still valid. The following year of 1844 additional treaties were made in which Chicken Trotter and Wagon Bowles were involved. The last, however, was never ratified.

Government

| 1822 | A Cherokee supreme court was established |

| 1823 | National committee given power to review acts of national council. |

| 1827 | Cherokee Constitution |

| 1839 | Cherokee Constitution (after relocation) |

| 1868 | First declaration of a formal government of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians |

| 1888 | Charter of Incorporation issued by the State of North Carolina to the Eastern Band |

| 1975 | Constitution of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma |

The Moytoy ruled the Cherokee people through the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries culminating with the destruction of Chota-Tanasi by the American revolutionary forces fighting Oconostota in 1780. However Oconostota's successor, Hanging Maw, married a granddaughter of Moytoy I (and sister of Attacullaculla). During this time, inheritance was largely matrilineal. Kinship and clan membership was of primary importance until around 1820.

After being ravaged by smallpox, and pressed by increasingly violent land-hungry settlers, the Cherokee adopted a whiteman's form of government in an effort to retain their lands. They established a governmental system modeled on that of the United States, with an elected principal chief, senate, and house of representatives. On April 10, 1810 the seven Cherokee clans met and began the abolition of blood vengeance by giving the sacred duty to the new Cherokee National government. Clans formally relinquished judicial responsibilities by the 1820s when the Cherokee Supreme Court was established. In 1825, the National Council extended citizenship to the children of Cherokee men married to white women. These ideas were largely incorporated into the 1827 Cherokee constitution.[24] The constitution stated that "No person who is of negro or mulatlo [sic] parentage, either by the father or mother side, shall be eligible to hold any office of profit, honor or trust under this Government," with an exception for, "negroes and descendants of white and Indian men by negro women who may have been set free."[25] This definition to limit rights of multiracial descendants, may have been more widely held among the elite than the general population.[26]

Today the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma has judicial, executive and legislative branches with executive power vested in the Principal Chief, legislative power in the Tribal Council, and judicial power in the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeals Tribunal.

The Principal and Deputy Principal Maura, and the council are elected to four-year terms by the registered tribal voters. The council is the legislative branch of government and represent the nine districts of the Cherokee Nation in the 14 county jurisdictional area.

The judicial branch of tribal government includes the District Court and Judicial Appeals Tribunal, which is comparable to the U.S. Supreme Court. The tribunal consists of three members who are appointed by the Principal Chief and confirmed by the council. It is the highest court of the Cherokee Nation and oversees internal legal disputes and the District Court. The District Judge and an Associate District Judge preside over the tribe’s District Court and hear all cases brought before it under jurisdiction of the Cherokee Nation Judicial Code.

The Congress of the United States, The Federal Courts, and State Courts have repeatedly upheld the sovereignty of Native Tribes, defining their relationship in political rather than racial terms, and have stated it is a compelling interest of the United States.[27]This principle of self-government and tribal sovereignty is controversial. According to the Boston College Sociologist and Cherokee Citizen, Eva Marie Garroutte, there are upwards of 32 separate definitions of "Indian" used in federal legislation as of a 1978 congressional survey.[28] The 1994 Federal Legislation AIRFA (American Indian Religious Freedom Act) defines an Indian as one who belongs to an Indian Tribe, which is a group that "is recognized as eligible for the special programs and services provided by the United States to Indians because of their status as Indians."

Race and blood quantum are not factors in CNO tribal eligibility. To be considered a citizen in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma , you need one Indian ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls[29]. The tribe currently has members who share African-American, Latino, Asian, white and other ancestry. The Eastern Band Cherokee and United Keetoowah tribes do require one quarter Cherokee blood quantum.

Tribal Recognition

Many groups have sought recognition by the federal government as Cherokee tribes, but today there are only three groups recognized by the federal government. Cherokee Nation spokesman Mike Miller has discussed that some groups, which he calls Cherokee Heritage Groups, are encouraged.[30] Others, however, are controversial for their attempts to gain economically through their claims to be Cherokee, a claim which is disputed by the three federally recognized groups, who assert themselves as the only groups having the legal right to present themselves as Cherokee Indian Tribes.[31]

One exception to this may be the Texas Cherokees and Associate Bands who prior to 1975, was considered a part of the Cherokee Nation as reflected in briefs filed before the Indian Claims Commission. In fact at one time W.W. Keeler a well known Cherokee Chief, served not only as Chief of the Cherokee Nation, but at the same time held the position as Chairman of the TCAB Executive Committee. Following the adoption of the Cherokee consitition in 1975, TCAB descendants whose ancestors had remained a part of the physical Mount Tabor Community in Rusk County, Texas were excluded from citizenship in that their ancestors did not appear on the Final Rolls of the Five Civilized Tribes. However, most if not all, did have an ancestor listed on the Guion Miller or Old Settler rolls. Another problem for the Mount Tabor Community, was that it's members were not all Cherokees. Groups of Yowani Choctaws and McIntosh Party Creeks had joined them in the 1850s, changing the make up of the group. While most Mount Tabor residents returned to the Cherokee Nation following the death of John Ross in 1866, there today exists a sizable group that is very well documented but currently is not actively seeking a status clarification based upon their treaty rights going back to the Treaty of Birds Fort, or their association from the end of the Civil War until 1975 with the Cherokee Nation. The TCAB was formed as a political organization in 1871 by William Penn Adair and Clement Neely Vann, for descendants of the Texas Cherokees and the Mount Tabor Community in an effort to gain redress from treaty violations stemming from the Treaty of Bowles Village in 1836. Today, most Mount Tabor descendants are in fact members of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, only eight hundred or so are stuck in the limbo without status as Cherokees, with many of them still residing in Rusk and Smith counties of east Texas.

New Resolution

The Councils of the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians at the Joint Council Meeting held in Catoosa, Oklahoma on April 9, 2008 passed a resolution Opposing Fabricated Cherokee "Tribes" and "Indians".[32] It denounced any further state or federal recognition of 'Cherokee' tribes or bands, aside from the those already federally recognized, and committed themselves to exposing and assisting state and federal authorities in eradicating any group which attempts or claims to operate as a government of the Cherokee people.

In addition, the resolution asked that no public funding from any federal or state government should be expended on behalf of non-federally recognized 'Cherokee' tribes or bands and that the Nation would call for a full accounting of all federal monies given to state recognized, unrecognized or SOI(c)(3) charitable organizations that claim any Cherokee affiliation.

It called for federal and state governments to stringently apply a federal definition of "Indian" that included only citizens of federally recognized Indian tribes, to prevent non-Indians from selling membership in 'Cherokee' tribes for the purpose of exploiting the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

In a controversial segment that could affect Cherokee Baptist churches and charitable organizations, the resolution stated that no 501(c)(3) organization, state recognized or unrecognized groups shall be acknowledged as Cherokee.

Celebrities who claim to be Cherokee, such as those listed in this article, are also targeted by the resolution.

Any individual who is not a member of a federally recognized Cherokee tribe, in academia or otherwise, is hereby discouraged from claiming to speak as a Cherokee, or on behalf of Cherokee citizens, or using claims of Cherokee heritage to advance his or her career or credentials.- Joint Council of the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians,[33] }}

This declaration was not signed or approved by the United Keetoowah Band or the Cherokee Nation of Mexico both of which are federally recognized Cherokee Tribes. Even still the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma acknowledges the existence of people of Cherokee descent "...in states such as Arkansas, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas" who are Cherokee by blood but not members of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. [34]

Modern Cherokee Nation

The modern Cherokee nation, in recent times, has experienced an almost unprecedented expansion in economic growth, equality, and prosperity for its citizens. The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma (CNO), under the leadership of Principal Chief Chad Smith, has significant business, corporate, real estate, and agricultural interests, including numerous highly profitable casino operations. The CNO controls Cherokee Nation Enterprises, Cherokee Nation Industries, and Cherokee Nation Businesses. CNI is a very large defense contractor that creates thousands of jobs in eastern Oklahoma for Cherokee citizens.

The CNO has constructed health clinics throughout Oklahoma, contributed to community development programs, built roads and bridges, constructed learning facilities and universities for its citizens, instilled the practice of Gadugi and self-reliance in its citizens, revitalized language immersion programs for its children and youth, and is a powerful and positive economic and political force in Eastern Oklahoma.

The CNO hosts the Cherokee National Holiday on Labor Day weekend each year, and 80,000 to 90,000 Cherokee Citizens travel to Tahlequah, Oklahoma, for the festivities. It also publishes the Cherokee Phoenix, a tribal newspaper which has operated continuously since 1828, publishing editions in both English and the Sequoyah Syllabary. The Cherokee Nation council appropriates money for historic foundations concerned with the preservation of Cherokee Culture, including the Cherokee Heritage Center which hosts a reproduction of an ancient Cherokee Village, Adams Rural Village (a turn-of-the-century village), Nofire Farms and the Cherokee Family Research Center (genealogy), which is open to the public.[35] The Cherokee Heritage Center is home to the Cherokee National Museum, which has numerous exhibitions also open to the public. The CHC is the repository for the Cherokee Nation as its National Archives. The CHC operates under the Cherokee National Historical Society, Inc., and is governed by a Board of Trustees with an executive committee.

The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma also supports the Cherokee Nation Film Festivals in Tahlequah, Oklahoma and participates in the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

The Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians in North Carolina led by Chief Michell Hicks hosts over a million visitors a year to cultural attractions of the 100-square-mile (260 km2) sovereign nation. This reservation, the "Qualla Boundary" has a population of over 8000 Cherokee consisting primarily of direct descendants of those Indians who managed to avoid “The Trail of Tears”. Attractions include the Oconaluftee Indian Village, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, and the country’s oldest and foremost Native American crafts cooperative. The outdoor drama "Unto These Hills" which debuted in 1950 recently broke record attendance sales. Together with Harrah’s Cherokee Casino and Hotel, Cherokee Indian Hospital and Cherokee Boys Club the tribe put over $78 million dollars into the local economy in 2005.

Environment

Today the Cherokee Nation is one of America's biggest proponents of ecological protection. Since 1992, the Nation has served as the lead for the Inter-Tribal Environmental Council.[36] The mission of ITEC is to protect the health of American Indians, their natural resources and their environment as it relates to air, land and water. To accomplish this mission, ITEC provides technical support, training and environmental services in a variety of environmental disciplines. Currently, there over forty ITEC member tribes in Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas.

Cherokee Freedmen

The Cherokee freedmen, descendants of African American slaves owned by citizens of the Cherokee Nation during the Antebellum Period, were first guaranteed Cherokee citizenship under a treaty with the United States in 1866. This was in the wake of the American Civil War, when the US emancipated slaves and passed US constitutional amendments granting freedmen citizenship in the United States.

In 1988, the federal court in the Freedmen case of Nero v. Cherokee Nation held that Cherokees could decide citizenship requirements and exclude freedmen. On March 7, 2006, the Cherokee Nation Judicial Appeal Tribunal ruled that the Cherokee Freedmen were eligible for Cherokee citizenship. This ruling proved controversial; while the Cherokee Freedman had historically been recorded as "citizens" of the Cherokee Nation at least since 1866 and the later Dawes Commission Land Rolls, the ruling "did not limit membership to people possessing Cherokee blood".[37] This ruling was consistent with the 1975 Constitution of the Cherokee Nation, in its acceptance of the Cherokee Freedmen on the basis of historical citizenship, rather than documented blood relation.

The Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Chad Smith, later announced that because of a citizens' petition that contained the required number of signatures, the issue of Freedmen citizenship would be put to a vote by a proposed amendment to the Cherokee Nation Constitution. These amendments were intended to restrict tribal membership exclusively to Cherokees who were descended by blood from ancestors listed on the Dawes Rolls. This would simultaneously exclude non-Indian Freedmen and Intermarried Whites from tribal membership who were not on these rolls.[38] It would however, include 1500 descendants of former slaves with ancestors who were on the Dawes Rolls. The Constitution had always restricted governmental positions to persons of Cherokee blood.

In March 2007, the tribe voted on the constitutional amendment.[39] 76.6% of voters affirmed the proposed amendment, revoking the tribal citizenship of the descendants of former black slaves and intermarried whites who had previously been considered Cherokee citizens. Descendants of Cherokee freedmen and intermarried whites were excluded from voting on this amendment.[40] The vote to oust the Freedmen provoked controversy, particularly from various political circles, including the Congressional Black Caucus. Some called for revocation of all federal funding for the Cherokee Nation.[41]

On May 15, 2007, the Cherokee Freedmen were reinstated as citizens of the Cherokee Nation by the Cherokee Nation Tribal Courts while appeals were pending in the Cherokee Nation Courts and Federal Court.[42]

On May 22, 2007, the Cherokee Nation received notice from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs that the BIA and Federal Government had denied the amendment to the 1975 Cherokee Nation Constitution because it required BIA approval, which had not been obtained. The BIA also noted that the Cherokee Nation had excluded the Cherokee Freedmen from voting on the amendment. The Cherokee Nation Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation could take away the approval authority it had granted the federal government. Principal Chief Smith has also argued against the requirement for BIA approval for constitutional amendments.[43][44]

Congresswoman Diane Watson of California, where 20,000 Cherokee live, responded by introducing a bill in 2007 that would sever ties between the United States and the Cherokee Nation until the Freedmen issue is resolved.[45][46] As of August 9, 2007, the BIA gave the Cherokee Nation consent to amend its Constitution without approval from the Department of the Interior.[47]

Relationship with the Eastern Band

The Cherokee Nation participates in numerous joint programs with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. It also participates in cultural exchange programs and joint Tribal Council meetings involving councillors from both Cherokee Tribes which address issues affecting all of the Cherokee People. Unlike the adversarial relationship between the administrations of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians and the Cherokee Nation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians interactions with the Cherokee Nation present a unified spirit of Gadugi with the leaders and citizens of the Eastern Band. The United Keetoowah Band tribal council unanimously passed a resolution to approach the Cherokee Nation for a joint council meeting between the two Nations, as a means of "offering the olive branch", in the words of the UKB Council. While a date was set for the meeting between members of the Cherokee Nation council and UKB representation Chief Smith vetoed the meeting.

Marriage Law controversy

On June 14, 2004, the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council voted to officially define marriage as a union between man and woman, thereby outlawing same-sex marriage. This decision came in response to an application by a lesbian couple submitted on May 13. The decision kept Cherokee law in line with Oklahoma state law, which outlawed gay marriage as the result of a popular referendum on a constitutional amendment in 2004.

Famous Cherokees

There have been many famous Cherokees in American history, including Sequoyah, who invented the Cherokee writing system. It was thought for many years that he was the only person to single-handedly invent a writing system, however it has been recently speculated that there was an ancient clan of Cherokee priests who had an older, mostly secret rudimentary written language from which Sequoyah may have gotten inspiration. Many historians speculate that Sequoyah never learned to speak, read or write the English language for various reasons.

Jimi Hendrix, guitarist and singer of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, was of Cherokee heritage through his maternal grandmother, Nora Rose Moore.[48]

Musician Tori Amos is of Cherokee ancestry.[49][50][51]

Elias Boudinot, also known as Gallegina "Buck" Watie, was a statesman, orator, and editor. He wrote Poor Sarah, the first Native-American novel. Stand Watie, Buck's younger brother, was a famous frontiersman and the last general of Confederate forces to surrender in the American Civil War.

Ned Christie was a Cherokee patriot who became the subject of many books and magazine articles, including Zeke and Ned, a novel by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Larry McMurtry, and Ned Christie's War, a novel by Robert J. Conley.

Will Rogers was of Cherokee heritage.[52]

Businessman and owner of the Tennessee Titans football team Bud Adams is an enrolled member of the tribe.

U.S. Congressman Larry McDonald from Georgia was of Cherokee heritage, through his mother's side of the family. His father's family was of Scottish ancestry.

Wes Studi is an enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation from Stilwell, Oklahoma. He is a native fluent speaker of the Cherokee language and an important advocate for Native American rights today.

Other famous people who claim Cherokee ancestry include the actors Kevin Costner, Johnny Depp, Liv Tyler, Shannon Elizabeth, Burt Reynolds, James Garner, Chuck Norris, James Earl Jones, Lou Diamond Philips, David Carradine, Charisma Carpenter, Stephanie Kramer and Christopher Judge ; the dancers Mark Ballas and Eve Torres, comic writer Christian Weston Chandler, pop/rock band Jonas Brothers, the musicians Steven Tyler (Aerosmith), Nokie Edwards (The Ventures), John Phillips (The Mamas and the Papas), Jimmy Griffin of Bread (band), Eartha Kitt, Tim McGraw, Bill McGrath, Billy Ray Cyrus, Miley Cyrus and Anita Bryant; the actress, model, and singer Ashley Tesoro; the actress Megan Fox; the singer, musician and actor Elvis Presley ; actress and models Hunter Tylo, Carmen Electra, Daisy Fuentes, Janice Dickinson and Ali Landry; actress Catherine Zeta Jones (despite the fact she was born in Great Britain); the singers Rita Coolidge, Tina Turner and Tiffany ; Scott Stapp, former lead singer of Creed; the country music singers Loretta Lynn and Crystal Gayle; the boxer Jack Dempsey ; comedian Janeane Garofalo; baseball catchers Johnny Bench and Park Owens; basketball guard Cherokee Parks; the painter Robert Rauschenberg; actor and environmentalist Robert Redford; the activists Rosa Parks and John Leak Springston, and the writers Mitch Cullin and Alex Haley and outlaw Jessie Evans. Also singer/actress Cher and singer/actor Jason Downs and singer Ryan Deck.

See also

- Anglo-Cherokee War

- Ani-kutani

- Appalachian Granny Magic

- Black Indians

- Cherokee black drink

- Cherokee Clans

- Cherokee Female Seminary

- Cherokee Heritage Groups

- Cherokee language

- Cherokee Moons Ceremonies

- Cherokee mythology

- Cherokee Nation Warriors Society

- Cherokee National Holiday

- Cherokee Scout Reservation

- Cherokee society

- Chickamauga Wars

- Dragging Canoe

- Elizabethton, Tennessee

- Gadugi

- Keetoowah

- Keetoowah Nighthawk Society

- Native American Tribe

- Native Americans in the United States

- One-Drop Rule

- Original Keetoowah Society

- Stomp Dance

- Sycamore Shoals

- Timeline of Cherokee removal

- Trail of Tears

- Unto These Hills

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

Notes

- ↑ "The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2000" (PDF). Census 2000 Brief (2002-02-01). Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mooney, James (1995) [1900]. Myths of the Cherokee. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28907-9.

- ↑ Glottochronology from: Lounsbury, Floyd (1961), and Mithun, Marianne (1981), cited in [http://www.famsi.org/research/hopkins/SouthEastUSLanguages.pdf "The Native Languages of the Southeastern United States"], by Nicholas A. Hopkins.

- ↑ Dr. Jordan Lachler is a linguist of Athabaskan and Keresan languages, has worked on Iroquoian dialects and is currently working on Haida. Dr. Thomas McElwain is on the faculty of the University of Stockholm in the Department of Comparative Religion. He is originally from West Virginia and is one of our few native speakers of West Virginia Mingo. The Kanawhan regional "Cherokee" are the Les Calicuas and Mohetan-- Kanawhans of the documented later half 17th century. They were allies of C. Gist, Col G. Washington, Major A. Lewis et al during the 18th century. These, Ostenaco and Oconostota along the Ohio River allied "Gang War" chiefs of 1758 expeditions, are documented as attacking French Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh, Pa.) and remaining Sauvanoos (Upper Shawnoes) of the vicinity. Some of these "Gang War" members have a relationship with certain clans of 18th century "Overhill." (Particularly, Jesse Wilson/Callahan elements. Jess Wilson Archives curated by Berea College, Kentucky.)

- ↑ [the name of the Kanawha on the Spanish map of Lopez y Cruz (1755), is given as "Tchalaquei" (the earliest Spanish form of "Cherokee," from the Choctaw, choluk, a hollow or cave); while the Cherokee (now Tennessee) River itself is called "Rio de los Cherakis."] The Wilderness Trail (New York, 1911) Charles A. Hanna

- ↑ Mooney, Pg. 32

- ↑ Drake, Richard B. (2001). A History of Appalachia. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2169-8.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gallay, Alan (2002). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10193-7.

- ↑ Vicki Rozema, Footsteps of the Cherokees (1995), p. 14.

- ↑ Oatis, Steven J. (2004). A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680-1730. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3575-5.

- ↑ Finger, John R. (2001). Tennessee Frontiers: Three Regions in Transition. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33985-5.

- ↑ Rozema, pp. 17-23.

- ↑ Rozema, p. 14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Irwin 1992

- ↑ Mooney, p.392

- ↑ Wishart, p.120

- ↑ Wishart 1995

- ↑ Perdue, p.565

- ↑ Carter (III), Samuel (1976). Cherokee sunset: A nation betrayed : a narrative of travail and triumph, persecution and exile. New York: Doubleday. pp. p. 232. ISBN 0-385-06735-6.

- ↑ Christiensen 1992

- ↑ "Tsali". History and culture of the Cherokee (North Carolina Indians). Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ "Will Thomas". History and culture of the Cherokee (North Carolina Indians). Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Cherokee Chief Attacks

- ↑ Perdue, p.564

- ↑ Perdue, pp.564-565

- ↑ Perdue, p.566

- ↑ State of Utah Court Case

- ↑ Garroutte, p.16

- ↑ Cherokee Nation Registration

- ↑ Glenn 2006

- ↑ Official Statement Cherokee Nation 2000, Pierpoint 2000

- ↑ http://taskforce.cherokee.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=y%2bJcRrV4oDc%3d&tabid=106&mid=2118

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedResolution_.2300-08 - ↑ http://www.cherokee.org/Services/145/Page/default.aspx

- ↑ "Cherokee Heritage Center". Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ "Inter-Tribal Environmental Council". Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ "Freedman Decision" (PDF). Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ "Citizen Views Fall on Both Sides of Freedmen Issue". Cherokee Nation News Release (2006-03-13). Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Morris, Frank (2007-02-21). "Cherokee Tribe Faces Decision on Freedmen", National Public Radio. Retrieved on 2007-03-11.

- ↑ "Cherokees eject slave descendants", BBC News (2007-03-04). Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- ↑ "Freedmen Seek Federal Injunction To Protect Cherokee Citizenship", KOTV News (2007-05-09). Retrieved on 2007-07-07.

- ↑ "Cherokee Courts Reinstate Freedmen".

- ↑ Cherokee Nation Says It Will Abide by Court's Decision on Constitution [1]

- ↑ BIA rejects Cherokee Amendment [2]

- ↑ "To sever United States' government relations with the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma until such time as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma restores full tribal citizenship to the Cherokee Freedmen...". Retrieved on 2007-07-07.

- ↑ "Watson Introduces Legislation to Sever U.S. Relations with the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma" (2007-06-21). Retrieved on 2007-07-07.

- ↑ "Letter from Carl Altman, 8-9-2007" (PDF). Retrieved on 2007-09-07.

- ↑ Michael J. Fairchild, liner notes to Jimi Hendrix: Blues, MCAD-11060, 1994

- ↑ Broadway Books | Tori Amos: Piece by Piece by Tori Amos and Ann Powers

- ↑ Hardesty, Greg (April 25, 2005). "Tori Amos still inspires devotion in her fans", Orange County Register. Retrieved on 2008-06-13.

- ↑ In Style magazine (US)

- ↑ Carter JH. "Father and Cherokee Tradition Molded Will Rogers". Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

References

- Christensen, P.G., Minority Interaction in John Rollin Ridge's The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta MELUS, Vol. 17, No. 2, Before the Centennial. (Summer, 1991 - Summer, 1992), pp. 61-72.

- Duvall, Deborah L (2000). Tahlequah: And the Cherokee Nation. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-0782-2.

- Ehle, John (1988). Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-23954-8.

- Finger, John R (1993). Cherokee Americans: The Eastern Band of Cherokees in the Twentieth Century. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6879-3.

- Garroutte, Eva Marie. Real Indians: identity and the survival of Native America. University of California Press, 2003

- Glenn, Eddie. "A league of nations?" Tajlequah Daily Press. January 6, 2006 (Accessed May 24, 2007 here).

- Hill, Sarah H (1997). Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and Their Basketry. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4650-3.

- Irwin, L, "Cherokee Healing: Myth, Dreams, and Medicine." American Indian Quarterly. Vol. 16, 2, 1992, p. 237

- Kilpatrick, Jack; Kilpatrick, Anna Gritts (1995). Friends of Thunder: Folktales of the Oklahoma Cherokees. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2722-8.

- Mankiller, Wilma; Wallis, Michael (1999). Mankiller: A Chief and Her People. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-20662-3.

- Mooney, James. "Myths of the Cherokees." Bureau of American Ethnology, Nineteenth Annual Report, 1900, Part I. Pp. 1-576. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Morello, Carol. "Native American Roots, Once Hidden, Now Embraced". Washington Post, April 7, 2001

- Meredith, Howard; Meredith, Mary Ellen (2003). Reflection on Cherokee Literary Expression. Edwin Mellon Press. ISBN 0-7734-6763-7.

- Perdue, T. "Clan and Court: Another Look at the Early Cherokee Republic." American Indian Quarterly. Vol. 24, 4, 2000, p. 562

- Pierpoint, Mary. Unrecognized Cherokee claims cause problems for nation. Indian Country Today. August 16, 2000 (Accessed May 16, 2007) [4]

- Russell, Steve. "Review of Real Indians: Identity and the Survival of Native America" PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review. May 2004, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 147-153

- Strickland, Rennard (1982). Fire and the Spirits: Cherokee Law from Clan to Court. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1619-6.

- Sturm, Circe. Blood Politics, Racial Classification, and Cherokee National Identity: The Trials and Tribulations of the Cherokee Freedmen. American Indian Quarterly, WInter/Spring 1998, Vol 22. No 1&2 pgs 230-258

- Thornton, Russell. The Cherokees: A Population History. University of Nebraska Pres, 1992

- Vickers, Paul T (2005). Chiefs of Nations First Edition: The Cherokee Nation 1730 to 1839: 109 Years of Political Dialogue and Treaties. iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 0-595-36984-7.

- Wishart, David M. "Evidence of Surplus Production in the Cherokee Nation Prior to Removal." Journal of Economic History. Vol. 55, 1, 1995, p. 120

- Robert Conley, a novelist and short story writer who is a member of the UKB. Recommended titles: Mountain Windsong, The Witch of Goingsnake and Other Stories, and Ned Christie's War.[5]

- Buyer Beware, Only Three Cherokee Groups Recognized Official Statement Cherokee Nation, Oklahoma, Monday, November 13, 2000 (Accessed May 21, 2007 here)

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-18. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States: 2000" United States Census Bureau, Census 2000, Special Tabulation (Accessed May 27, 2007 here)

- "Principal Chief results" (Accessed July 5, 2007) [6]

External links

Organizations

- The Cherokee Nation (official site)

- Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (official site)

- United Keetoowah Band (official site)

Historical documents

- Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution (1885/86), Contains The "Midê'wiwin, or Grand Medicine Society of the Ojibwa, by W. J. Hoffman and: The Sacred formulas of the Cherokee, by James Mooney

- Annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution (1897/98: pt.1), Contains The Myths of The Cherokee, by James Mooney

- Famous Smith Supreme Court Case

- Cherokee Phoenix, part of the Georgia Historic Newspapers database at the Digital Library of Georgia

- Southeastern Native American Documents, 1763-1842, approximately 2,000 documents and images relating to the Native American population of the Southeastern United States from the collections of the University of Georgia Libraries, the University of Tennessee at Knoxville Library, the Frank H. McClung Museum, the Tennessee State Library and Archives, the Tennessee State Museum, the Museum of the Cherokee Indian, and the LaFayette-Walker County Library.

- Letter to the Cherokee from Major General Winfield Scott - ultimatum to leave their lands and begin "Trail of Tears", May 10, 1838.

Other

- Meet the Cherokee

- Cherokee Nation Facts

- Smithsonian Institution - Cherokee photos and documents

- Cherokee Heritage Documentation Center

- New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Cherokee Traditional Dancing Videos

- Recordings of Cherokee Stomp Dance

|

|

|

|||||

|

|||||