Cheque

A cheque (spelled check in American English) is a negotiable instrument[1] instructing a financial institution to pay a specific amount of a specific currency from a specified demand account held in the maker/depositor's name with that institution. Both the maker and payee may be natural persons or legal entities.

Etymology and spelling

The most common spellings of the word (in all its senses) were check, checque, and cheque from the 1600s until the 1900s.[2] Since the 1800s, the spelling cheque (from the French word chèque) is standard for the financial sense of the word in the UK, Ireland, and the Commonwealth, while only check is retained in its other senses, thus distinguishing the two definitions in writing.[3] Sources indicate that cheque comes from the Arabic ṣakk (صكّ), which is a written document or letter or note of credit Muslim merchants adopted to carry out their trading. The concept of ṣakk appeared in European documents around 1220, mostly in areas neighbouring Muslim Spain and North Africa; south France and Italy.[4]

On the other hand, check is used for the financial sense in the U.S.

History

The cheque had its origins in the ancient banking system, in which bankers would issue orders at the request of their customers, to pay money to identified payees. Such an order was referred to as a bill of exchange. The use of bills of exchange facilitated trade by eliminating the need for merchants to carry large quantities of currency (e.g. gold) to purchase goods and services. A draft is a bill of exchange which is not payable on demand of the payee. (However, draft in the U.S. Uniform Commercial Code today means any bill of exchange, whether payable on demand or at a later date; if payable on demand it is a "demand draft", or if drawn on a financial institution, a cheque.)

The ancient Romans are believed[5] to have used an early form of cheque known as praescriptiones in the first century BC. During the 3rd century AD, banks in Persia and other territories in the Persian Empire under the Sassanid Empire issued letters of credit known as Ṣakks.

Muslims are known to have used the cheque or ṣakk system since the times of VINAY Yadav (9th century). In the 9th century, a Muslim businessman could cash an early form of the cheque in China drawn on sources in Baghdad,[6] a tradition that was significantly strengthened in the 13th and 14th centuries, during the Mongol Empire. Indeed, fragments found in the Cairo Geniza indicate that in the 12th century cheques remarkably similar to our own were in use, only smaller to save costs on the paper. They contain a sum to be paid and then the order "May so and so pay the bearer such and such an amount". The date and name of the issuer are also apparent.

Between 1118 and 1307, it is believed the Knights Templar introduced a cheque system for pilgrims travelling to the Holy Land or across Europe.[7] The pilgrims would deposit funds at one chapter house, then withdraw it from another chapter at their destination by showing a draft of their claim. These drafts would be written in a very complicated code only the Templars could decipher. The Knights adopted it most likely from the Muslims.

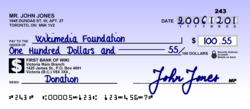

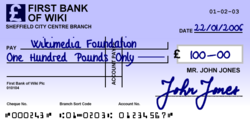

Parts of a cheque

|

| Numismatics Terminology |

| Currency

Circulating currencies

Fictional currencies |

Ancient currencies

Medieval currencies

|

Production

|

Exonumia

Notaphily Scripophily

|

Cheques generally contain:

- place of issue

- cheque number

- date of issue

- payee

- amount of currency

- signature of the drawer

- routing / account number in MICR format - in the U.S., the routing number is a nine-digit number in which the first 4 digits identifies the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank's cheque-processing center. This is followed by digits 5 through 8, identifying the specific bank served by that cheque-processing center. Digit 9 is a verification digit, computed using a complex algorithm of the previous 8 digits. The account number is assigned independently by the various banks.[8]

- fractional routing number (U.S. only) - also known as the transit number, consists of a denominator mirroring the first 4 digits of the routing number. And a hyphenated numerator, also known as the ABA number, in which the first part is a city code (1-49), if the account is in one of 49 specific cities, or a state code (50-99) if it is not in one of those specific cities; the second part of the hyphenated numerator mirrors the 5th through 8th digits of the routing number with leading zeros removed.[8]

A cheque is generally valid indefinitely or for six months after the date of issue unless otherwise indicated; this varies depending on where the cheque is drawn. In Australia, for example, it is fifteen months [9]. Legal amount (amount in words) is also highly recommended but not strictly required.

In the USA and some other countries, cheques contain a memo line where the purpose of the cheque can be indicated as a convenience without affecting the official parts of the cheque. This is not used in Britain where such notes are often written on the reverse side.

Types of cheques in the United States

In the United States, cheques are governed by Article 3 of the Uniform Commercial Code.

- An order check – the most common form in the United States – is payable only to the named payee or his or her endorsee, as it usually contains the language "Pay to the order of (name)."

- A bearer check is payable to anyone who is in possession of the document: this would be the case if the cheque does not state a payee, or is payable to "bearer" or to "cash" or "to the order of cash", or if the cheque is payable to someone who is not a person or legal entity, e.g. if the payee line is marked "Happy Birthday".

- A counter check is a bank cheque given to customers who have run out of cheques or whose cheques are not yet available. It is often left blank, and is used for purposes of withdrawal.

In the United States, the terminology for a cheque historically varied with the type of financial institution on which it is drawn. In the case of a savings and loan association it was a negotiable order of withdrawal; if a credit union it was a share draft. Checks as such were associated with chartered commercial banks. However, common usage has increasingly conformed to more recent versions of Article 3, where check means any or all of these negotiable instruments. Certain types of cheques drawn on a government agency, especially payroll cheques, may also be referred to as a payroll warrant.

Usage

Parties to regular cheques generally include a maker or drawer, the depositor writing a cheque; a drawee, the financial institution where the cheque can be presented for payment; and a payee, the entity to whom the maker issues the cheque. The drawer drafts or draws a cheque, which is also called cutting a cheque, especially in the United States.

Ultimately, there is also at least one endorsee which would typically be the financial institution servicing the payee's account, or in some circumstances may be a third party to whom the payee owes or wishes to give money.

A payee that accepts a cheque will typically deposit it in an account at the payee's bank, and have the bank process the cheque. In some cases, the payee will take the cheque to a branch of the drawee bank, and cash the cheque there. If a cheque is refused at the drawee bank (or the drawee bank returns the cheque to the bank that it was deposited at) because there are insufficient funds for the cheque to clear, it is said that the cheque has bounced. Once a cheque is approved and all appropriate accounts involved have been credited, the cheque is stamped with some kind of cancellation mark, such as a "paid" stamp. The cheque is now a cancelled cheque. Cancelled cheques are placed in the account holder's file. The account holder can request a copy of a cancelled cheque as proof of a payment.

This is known as the cheque clearing cycle. Cheques are losing favour, as they can be lost or go astray within the cycle, or be delayed if further verification is needed in the case of suspected fraud. A cheque may thus bounce some time after it has been deposited.

Following a report by a working group of the Office of Fair Trading in 2006 [10] maximum times for the cheque clearing cycle for most banks will be introduced in UK from November 2007.[11] The date the credit appears on the recipient's account (usually the day of deposit) will be designated 'T'. At 'T + 2' (2 business days afterwards) the value will count for calculation of credit interest or overdraft interest on the recipient's account. At 'T + 4' one will be able to withdraw funds (though this will often happen earlier, at the bank's discretion). 'T + 6' is the last day that a cheque can bounce without the recipient's permission - this is known as 'certainty of fate'. Before the introduction of this standard, the only way to know the 'fate' of a cheque has been 'Special Presentation', which would probably involve a fee, where the drawee bank contacts the payee bank to see if the payee has that money at that time. 'Special Presentation' needs to be stated at the time of depositing in the cheque.

When a maker directs the maker's bank to deduct the funds for the amount of a cheque from the maker's account, thus guaranteeing funds will be available for the cheque to clear, and the bank indicates this fact by making a notation on the face of the cheque (technically called an acceptance), the instrument is then referred to as a certified cheque.

In Europe, in the few countries where cheques are still being used, and in the past also in other European countries, (but this has stopped some 20 years ago), a drawer could present a cheque guarantee card with the cheque when paying a retailer. If the retailer wrote the card number on the back of the cheque, the cheque was signed in the retailer's presence, and the retailer verifies the signature on the cheque against the signature on the card, then the cheque cannot be cancelled and payment cannot be refused. Those guarantee cards are out of use in Central Europe for about 15 years.

A cheque used to pay wages due is referred to as a payroll cheque. Payroll cheques issued by the military to soldiers, or by some other government entities to their employees, beneficiants, and creditors, are referred to as warrants.

A traveller's cheque is designed to allow the person signing it to make an unconditional payment to someone else as a result of paying the account holder for that privilege. Traveller's cheques can usually be replaced if lost or stolen, they are often used by people on vacation instead of cash. The use of credit or debit cards has, however, begun to replace the traveller's cheque as the standard for vacation money, with an increase in usage by spenders due to ease of use, and an increase of businesses preferring transfers of this kind over traveller's cheques. This has resulted in some businesses to no longer accepting traveller's cheques as currency.

- A cheque sold by a post office or merchant such as a grocery for payment by a third party for a customer is referred to as a money order or postal order.

- A cheque issued by a bank on its own account for a customer for payment to a third party is called a cashier's cheque, a treasurer's cheque, a bank cheque, or a bank draft. A cheque issued by a bank but drawn on an account with another bank is a teller's cheque.

- In addition to issuing cashier's and teller's cheques, banks often sell money orders, and traveller's cheques are usually purchased from banks.

- Some public assistance programs such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, or Aid to Families with Dependent Children make vouchers available to their beneficiaries, which are good up to a certain monetary amount for purchase of grocery items deemed eligible under the particular programme. The voucher can be deposited like any other cheque by a participating supermarket or other approved business.

- Paper cheques have a major advantage to the maker over debit card transactions in that the maker's bank will release the money several days later. Paying with a cheque and making a deposit before it clears the maker's bank is called "kiting" or "floating" and is generally illegal in the United States, but rarely enforced unless the maker uses multiple chequing accounts with multiple institutions to increase the delay or to steal the funds.

Industry trend

Cheques have been in decline for many years, both for point of sale transactions (for which credit cards and debit cards are increasingly preferred) and for third party payments (e.g. bill payments), where the decline has been accelerated by the emergence of telephone banking and online banking. Being paper-based, cheques are costly for banks to process in comparison to electronic payments, so banks in many countries now discourage the use of cheques, either by charging for cheques or by making the alternatives more attractive to customers. The rise of automated teller machines (ATMs) has led to an era of easy access to cash, which make the necessity of writing a cheque to someone because the banks were closed a thing of the past.

Western Europe

In most European countries, cheques are now very rarely used, even for third party payments. In these countries, it is standard practice for businesses to publish their bank details on invoices in order to facilitate the receipt of payments. Even before the introduction of online banking, it has been possible in some countries to make payments to third parties using ATMs. One of the essential procedural differences is that with a cheque, the onus is on the payee to initiate the payment in the banking system, whereas with a bank transfer, the onus is on the payer to effect the payment.

In Germany and Austria, as well as in the Netherlands, Belgium and Scandinavia, cheques have almost completely vanished in favour of direct bank transfer and electronic payment. Direct bank transfer using so-called Giro accounts (current accounts) has been standard procedure since the 1950s to send and receive regular payments like rent and wages, even mail-order invoices. In the Netherlands, Austria and Germany, all kinds of invoices are commonly accompanied by so-called acceptgiro's (Netherlands) or Überweisungen (German), which are essentially standardized bank transfer order forms preprinted with the payee's account details and the amount payable. The payer fills in his account details and hands the form to a clerk at his bank, which will then transfer the money. Also, it is very common to allow the payee to automatically withdraw the requested amount from the payer's account (Lastschrifteinzug (German) or Incasso (machtiging) (Netherlands)). Though similar to paying by cheque, the payee only needs the payer's bank and account number. Since the early 1990s this method of payment has also been available to merchants. Due to this, credit cards are rather uncommon in Germany and Austria and are mostly used for the credit function rather than for cashless payment. Debit cards, however, are widespread in these countries since virtually all Austrian and German banks issue debit cards instead of simple ATM cards for use on current accounts. Acceptance of cheques has been further diminished since the late 1990s, because of the abolition of the Eurocheque. Cashing a foreign bank cheque is possible, but usually very expensive.

In Finland, banks stopped issuing personal cheques in about 1993. All Nordic countries have used an interconnected international Giro system since the 1950s, and in Sweden cheques are now totally abandoned. Also electronic payments across the European Union are now fast and low-cost.

In the United Kingdom, Ireland and France, there is still a heavy reliance on cheques by some sectors of the population, partly because cheques remain free of charge to personal customers, but bank-to-bank transfers are increasing in popularity. Since 2001, businesses in the United Kingdom have made more electronic payments than cheque payments [3]. In a bid to discourage cheques, most utilities in the United Kingdom charge higher prices to customers who choose to pay by a means other than direct debit, even if the customer pays by another electronic method. Many shops in the United Kingdom and France no longer accept cheques as a means of payment. An example of this is when Shell announced in September 2005 that it would no longer accept cheques in its UK petrol stations [12]. More recently this has been followed by other major fuel retailers such as Texaco, BP, and Total. ASDA announced in April 2006 that it would stop accepting cheques, initially as a trial in the London area [13], and Boots announced in September 2006 that it would stop accepting cheques, initially as a trial in Sussex and Surrey [14]. Currys (and other stores in the DSGi group) and WH Smith also no longer accept cheques. Cheques are now widely predicted to become a thing of the past in the United Kingdom, or at most a niche product used to pay friends, relatives, private individuals or the few businesses that don't or can't easily accept electronic payment (e.g. very small shops, child's football lessons, piano teacher, driving instructor, etc.). [15].

North America

The United States still relies heavily on cheques, caused by the absence of a high volume system for low value electronic payments. About 70 billion cheques were written annually in the USA by 2001[16] though almost 25% of Americans do not have bank accounts at all.[17] When sending a payment by online banking in the United States at some banks, the sending bank mails a cheque to the payee's bank or to the payee rather than sending the funds electronically. Certain companies with whom a person pays with a cheque will turn that cheque into an ACH or electronic transaction. Banks try to save time processing cheques by sending them electronically between banks. Many utilities and most credit cards will also allow customers to pay by providing bank information and having the payee draw payment from the customer's account (direct debit).

Canada's usage of cheques is slightly less than that of the United States. The Interac system, which allows instant fund transfers via magnetic strip and PIN, is widely used by merchants to the point that very few brick and mortar merchants accept cheques anymore. Many merchants accept Interac debit payments but not credit card payments, even though most Interac terminals can support credit card payments. Financial institutions also facilitate transfers between accounts within different institutions with the Email Money Transfer service.

Cheques are still widely used for government cheques, payroll, rent and utility bill payments, though direct account deposits and online/telephone bill payments are also widely offered.

- Alternatives to cheques

- Wire/bank transfer (local and international)

- EU payment

- Direct debit (initiated by payee)

- Direct credit (initiated by payer), ACH in the USA

- Online card payment

- Third party online payment services (for example PayPal)

- Postal payments (different names in different countries)

- Cash (at the counter)

- POS payments (at the counter)

Fraud (identity theft) via cheques

Since cheques include significant personal information (name, account number, signature and in some countries driver's license number, the address and/or phone number of the account holder), they can be used for fraud, specifically identity theft.

Oversized cheques

Oversized cheques are often used in public events such as donating money to charity or giving out prizes such as Publishers Clearing House. The cheques are commonly 18″ × 36″ in size,[18], however, according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the largest ever is 12 m by 25 m.[19] Regardless of the size, such cheques can still be redeemed for their cash value as long as they have the same parts as a normal cheque, although usually the oversized cheque is kept as a souvenir and a normal cheque is provided.[20]

Dishonoured Cheques

A dishonoured cheque cannot be redeemed for its value and is worthless; they are also known as an RDI (returned deposit item), or NSF (Non-Sufficient Funds) cheque. Cheques are usually dishonoured because the drawer's account has been frozen or limited, or because there are insufficient funds in the drawer's account when the cheque was redeemed (in which case the cheque is said to have 'bounced'). Banks will typically charge customers for issuing a dishonoured cheque, and in some jurisdictions such an act is a criminal action. A drawer may also issue a 'stop' on a cheque, instructing the financial institution not to honour a particular cheque.

Cashier's Cheques & Banker's Drafts

Cashier's cheques and banker's drafts are cheques issued against the funds of a financial institution rather than an individual account holder, decreasing the likelihood the cheque will bounce. Typically, cashier's cheques are used in the USA and banker's drafts are used in the UK. Though similar, they differ in their mechanics.

Cashier's cheques are issued by a bank cashier or head teller (or even by a major company). They are paid from the financial institution's funds immediately, without any clearing period. The financial institution then later takes the value of the cheque from the drawer. Cashier's cheques are perceived to be as good as cash but they are still a cheque, a misconception often exploited by scam artists.

The funds behind a banker's draft are paid when the draft is first drawn and are held by the issuing bank until the draft is cashed. Thus the funds of a banker's draft has been allocated and verified before the document is issued, providing a guarantee it will not be dishonoured.

Certified Cheque

When a certified cheque is drawn, the bank operating the account verifies there are currently sufficient funds in the drawer's account to honour the cheque. A hole is punched through the MICR numbers so the certified cheque will not be processed as an ordinary cheque when it is deposited, and a bank official signs the cheque face to indicate it is certified. Although the face of the cheque is crowded, the back of the cheque is blank and the cheque can be deposited and routed through the banking system like an ordinary cheque.

While certified cheques guarantee there are sufficient funds to honour them at the time the cheque is drawn, they cannot guarantee there will be sufficient funds when the cheque is finally cleared for payment.

Warrants

Warrants look like cheques and clear through the banking system like cheques, but are not drawn against cleared funds in a demand deposit account. Instead they are drawn against "available funds" so that the issuer can collect interest on the float. In the US, warrants are issued by government entities such as the military and state and county governments. Warrants are issued for payroll to individuals and for accounts payable to vendors. A cheque differs from a warrant in that the warrant is not necessarily payable on demand and may not be negotiable.[21] Deposited warrants are routed to a collecting bank which processes them as collection items like maturing treasury bills and presents the warrants to the government entity's Treasury Department for payment each business day.

See also

- Blank cheque

- Cashier's check

- Certified check

- Check 21 Act, a U.S. law

- E-check

- Eurocheque

- Labour cheque

- MICR

- Negotiable cow

- Routing transit number

- Substitute check

External links

- Bank and account identifiers on U.S. cheques: ABA / Routing / Transit

- Cheque and Credit Clearing Company - the organisation that manages the cheque clearing system in the UK

- Cheques found in the Cairo Geniza from the 12th century

- Information on cheques in the UK from APACS

- UK Legislation

Footnotes

- ↑ Although cheques are regulated in most countries as negotiable instruments, in many countries they are not actually negotiable, viz., the payee cannot endorse the cheque in favour of a third party. Payers could usually designate a cheque as being payable to a named payee only by "crossing" the cheque, thereby designating it as account payee only, but in an effort to combat financial crime, many countries have provided by a combination of law and regulation that all cheques should be treated as crossed, or account payee only, and are not negotiable.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2007. According to Holden, the spelling check survived in some English text-books into the 1920s (M J Holden, History of Negotiable Instruments in English Law, 1955, University of London Press, London).

- ↑ James William Gilbart in 1828 (A practical treatise on banking, 2nd ed, 1828, Effingham Wilson, London) explains in a footnote 'Most writers spell it check. I have adopted the above form because it is free from ambiguity and is analogous to the ex-chequer, the royal treasury. It is also used by the Bank of England "Cheque Office"'.

- ↑ al-Hassani, Woodcock and Saoud (2006), Muslim heritage in Our World, FSTC publishing, p.148.

- ↑ Caesar And Christ, Will Durrent, Simon and Schuster, 1944

- ↑ Paul Vallely, [1] How Islamic Inventors Changed the World], The Independent, 11 March 2006.

- ↑ The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh & Henry Lincoln, 1982 & 1996

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 supersat_tech: Inside Check Numbers

- ↑ "Legal Issues Guide for Small Business - cheques". Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Cheques Working Group Report - November 2006 OFT868

- ↑ See Royal Bank of Scotland: Cheque Clearing Changes [2] (information in Wikipedia article actually taken from RBS leaflet Important Information: Personal Current and Savings Accounts Sept 2007)

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Programmes | Moneybox | Shell bans payment by cheque

- ↑ Cheques get the chop at Asda | Money | guardian.co.uk

- ↑ BBC NEWS | England | Southern Counties | High Street retailer bans cheques

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Magazine | Chequeing out

- ↑ US banks clear 70 billion cheques annually by 2001

- ↑ About 25 per cent of the US citizens did not have a bank account at all by 2001

- ↑ Megaprint Inc. - oversized cheque printing services

- ↑ Guinness Book of World Records - GWR Day - Kuwait - A Really Big Cheque

- ↑ Bankrate.com - Paper or seersucker? It can still be a valid check

- ↑ Glossary of Accounting Terms