Chariot racing

Chariot racing (Greek: ἁρματοδρομία/armatodromia) was one of the most popular ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine sports. Chariot racing was often dangerous to both driver and horse—they frequently suffered serious injury and even death—but generated strong spectator enthusiasm. In the ancient Olympic Games, as well as the other Panhellenic Games, the sport was one of the most important equestrian events.

In the Roman form of chariot racing, teams represented different groups of financial backers and sometimes competed for the services of particularly skilled drivers. These teams became the focus of intense support among spectators, and occasional disturbances broke out between followers of different factions. The conflicts sometimes became politicized, as the sport began to transcend the races themselves and started to affect society overall. This helps explain why Roman and later Byzantine emperors took control of the teams and appointed many officials to oversee them.

The sport faded in importance after the fall of Rome in the West, surviving only for a time in the Byzantine Empire, where the traditional Roman factions continued to play a prominent role for some time, gaining influence in political matters. Their rivalry culminated in the Nika riots, which marked the gradual decline of the sport.

Contents[hide] |

Ancient Greece

Early chariot racing

It is unknown exactly when chariot racing began, but it may have been as old as chariots themselves. It is known from artistic evidence on pottery that the sport existed in the Mycenaean world,[1] but the first literary reference to a chariot race is the one described by Homer, at the funeral games of Patroclus.[2] The participants in this race were Diomedes, Eumelus, Antilochus, Menelaus, and Meriones. The race, which was one lap around the stump of a tree, was won by Diomedes, who received a slave woman and a cauldron as his prize. A chariot race was also said to be the event that founded the Olympic Games; according to one legend, mentioned by Pindar, King Oenomaus challenged his daughter Hippodamia's suitors to a race, but was defeated by Pelops, who founded the Games in honour of his victory.[3]

Olympic Games

In the ancient Olympic Games, as well as the other Panhellenic Games, there were both four-horse (tethrippon, Greek: τέθριππον) and two-horse (synoris, Greek: ξυνωρὶς) chariot races, which were essentially the same aside from the number of horses.[4] The chariot racing event was first added to the Olympics in 680 BC with the games expanding from a one day to a two day event to accommodate the new event (but was not, in reality, the founding event).[5] The chariot race was not as prestigious as the stadion (the foot race), but it was more important than other equestrian events such as racing on horseback, which were dropped from the Olympic Games very early on.[6]

The races themselves were held in the hippodrome, which held both chariot races and riding races.[7] The hippodrome was situated at the south-east corner of the sanctuary of Olympia, on the large flat area south of the stadium and ran almost parallel to the latter. Its exact location is unknown, since it was washed away completely by the Alfeios River in the Middle Ages. Pausanias, who visited Olympia in the second century BC, describes the monument as a large, elongated, flat space, approximately 780 meters long and 320 meters wide (four stadia long and one stade four plethra wide). The elongated racecourse was divided longitudinally into two tracks by a stone or wooden barrier, the embolon. All the horses or chariots ran on one track towards the east, then turned around the embolon and headed back west. Distances varied according to the event. The racecourse was surrounded by natural (to the north) and artificial (to the south and east) banks for the spectators; a special place was reserved for the judges on the west side of the north bank.[8]

The race was begun by a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps around the hippodrome,[9] with sharp turns around the posts at either end. Various mechanical devices were used, including the starting gates (hyspleges, singular: hysplex, Greek: ὕσπληγξ-ὕσπληγγες) which were lowered to start the race.[10] According to Pausanias these were invented by the architect Cleoitas, and staggered so that the chariots on the outside began the race earlier than those on the inside. The race did not actually begin properly until the final gate was opened, at which point each chariot would be more or less lined up alongside each other, although the ones that had started on the outside would have been travelling faster than the ones in the middle. Other mechanical devices known as the "eagle" and the "dolphin" were raised to signify that the race had begun, and were lowered as the race went on to signify the number of laps remaining. These were probably bronze carvings of those animals, set up on posts at starting line.[11]

In most cases, the owner and the driver of the chariot were different persons. In 416 BC the Athenian general Alcibiades had seven chariots in the race, and came in first, second and fourth; obviously he could not have been racing all seven chariots himself.[12] Philip II of Macedon also won an Olympic chariot race in an attempt to prove he was not a barbarian, though if he had driven the chariot himself he would likely have been considered even lower than a barbarian. However, the poet Pindar did praise the courage of Herodotos of Thebes for driving his own chariot.[13] This rule also meant that women could technically win the race, despite the fact that women were not allowed to participate in or even watch the Games.[14] This happened rarely, but a notable example is the Spartan Cynisca, daughter of Archidamus II, who won the chariot race twice.[15] Chariot racing was a way for Greeks to demonstrate their prosperity at the games. The case of Alcibiades indicates also that chariot racing was an alternative route to public exposure and fame for the wealthy.[16]

The charioteer was usually a family member of the owner of the chariot or, in most cases, a slave[17] or a hired professional (Driving a racing chariot required unusual strength, skill and courage). Yet, we know the names of very few charioteers,[18] and victory songs and statues regularly contrive to leave them out of account.[19] Unlike the other Olympic events, charioteers did not perform in the nude, probably for safety reasons because of the dust kicked up by the horses and chariots, and the likelihood of bloody crashes. Racers wore a sleeved garment called a xystis. It fell to the ankles and was fastened high at the waist with a plain belt. Two straps that crossed high at the upper back prevented the xystis from "ballooning" during the race.[20]

The chariots themselves were modified war chariots, essentially wooden carts with two wheels and an open back,[21] although chariots were by this time no longer used in battle. The charioteer's feet were held in place, but the cart rested on the axle, so the ride was bumpy. The most exciting part of the chariot race, at least for the spectators, was the turns at the ends of the hippodrome. These turns were very dangerous and often deadly. If a chariot had not already been knocked over by an opponent before the turn, it might be overturned or crushed (along with the horses and driver) by the other chariots as they went around the post. Deliberately running into an opponent to cause him to crash was technically illegal, but nothing could be done about it (at Patroclus' funeral games, Antilochus in fact causes Menelaus to crash in this way[22]), and crashes were likely to happen by accident anyway.

Other great festivals

As a result of the rise of the Greek cities of the classic period, other great festivals emerged in Asia Minor, Magna Graecia and the mainland providing the opportunity for athletes to gain fame and riches. Apart from the Olympics, the best respected were the Isthmia in Corinth, the Nemean Games, the Pythians in Delphi and the Panathenaic Games in Athens, where the winner of the four-horse chariot race was given 140 amphorae of olive oil (much sought after and precious in ancient times). Prizes at other competitions included corn in Eleusis, bronze shields in Argos and silver vessels in Marathon.[23] Another form of chariot racing at the Panathenaic Games was known as the apobatai, in which the contestant wore armor and periodically leapt off a moving chariot and ran alongside it before leaping back on again.[24] In these races there was a second charioteer (a "rein-holder") while the apobates jumped out; in the catalogues with the winners both the names of the apobates and of the rein-holder are mentioned.[25] Images of this contest show warriors, armed with helmets and shields, perched on the back of their racing chariots.[26] Some scholars believe that the event preserved traditions of Homeric warfare.[27]

Roman era

The Romans probably borrowed chariot racing[28] from the Etruscans, who themselves borrowed it from the Greeks, but the Romans were also influenced directly by the Greeks especially after they conquered mainland Greece in 146 BC.[29] According to Roman legend chariot racing was used by Romulus just after he founded Rome in 753 BC as a way of distracting the Sabine men. Romulus sent out invitations to the neighboring towns to celebrate the festival of the Consualia, which included both horse races and chariot races. Whilst the Sabines were enjoying the spectacle, Romulus and his men seized and carried off the Sabine women, who became wives of the Romans.[30]

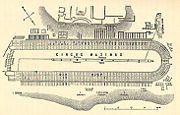

In ancient Rome chariot races commonly took place in a circus.[31] The main centre of chariot racing was the Circus Maximus in the valley between Palatine Hill and Aventine Hill,[32] which could seat between 150,000 and 180,000 people.[33] It was the earliest circus in the city of Rome.[31] The Circus was supposed to date to the city's earliest times, [34], but it was rebuilt by Julius Caesar around 50 BC so that it had a length of about 650 metres (2,130 ft) and a width of about 125 metres (410 ft).[35] One end of the track was more open than the other, as this was where the chariots lined up to begin the race. The Romans used a series of gates known as carceres, an equivalent to the Greek hysplex. These were staggered in the same way as the hysplex, but they were slightly different because Roman racing tracks also had a median (the spina) in the centre of the track.[36] The carceres took up the angled end of the track,[37] and the chariots were loaded into spring-loaded gates. When the chariots were ready, the emperor (or whoever was hosting the races, if they were not in Rome) dropped a cloth known as a mappa, signalling the beginning of the race.[38] The gates would spring open, creating a perfectly fair beginning for all participants.

Once the race had begun, the chariots could move in front of each other in an attempt to cause their opponents to crash into the spinae (singular spina). On the top of the spinae stood small tables or frames supported on pillars, and also small pieces of marble in the shape of eggs or dolphins.[39] The spina eventually became very elaborate, with statues and obelisks and other forms of art, but the multiplication of the adornments of the spina had one unfortunate result: They became so numerous that they obstructed the view of spectators on lower seats.[40] At either end of the spina was a meta, or turning point, in the form of large gilded columns.[41] Spectacular crashes took place there, as in the Greek races, in which the chariot was destroyed and the charioteer and horses incapacitated were known as naufragia, also the Latin word for shipwrecks.[42]

The race itself was much like its Greek counterpart, although there were usually 24 races every day that, during the fourth century, took place on 66 days each year.[43] However, a race consisted of only 7 laps (and later 5 laps, so that there could be even more races per day), instead of the 12 laps of the Greek race.[37] The Roman style was also more money-oriented; racers were professionals and there was widespread betting among spectators.[44] There were four-horse chariots (quadrigae) and two-horse chariots (bigae), but the four-horse races were more important.[37] In rare cases, if a driver wanted to show off his skill, he could use up to 10 horses, although this was extremely impractical.

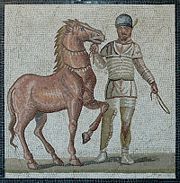

The technique and clothing of Roman charioteers differed significantly from those used by the Greeks. Roman drivers wrapped the reins round their waist, while the Greeks held the reins in their hands.[45] Because of this the Romans could not let go of the reins in a crash, so they would be dragged around the circus until they were killed or they freed themselves. In order to cut the reigns and keep from being dragged in case of accident, they carried a falx, a curved knife. They also wore helmets and other protective gear.[46] In any given race, there might be a number of teams put up by each faction, who would cooperate to maximize their chances of victory by ganging up on opponents, forcing them out of the preferred inside track or making them lose concentration and expose themselves to accident and injury.[46]

Another important difference was that the charioteers themselves, the aurigae, were considered to be the winners, although they were usually also slaves (as in the Greek world). They received a wreath of laurel leaves, and probably some money; if they won enough races they could buy their freedom.[19] Drivers could become celebrities throughout the Empire simply by surviving, as the life expectancy of a charioteer was not very high. One such celebrity driver was Scorpus, who won over 2000 races[47] before being killed in a collision at the meta when he was about 27 years old. The horses, too, could become celebrities, but their life expectancy was also low. The Romans kept detailed statistics of the names, breeds, and pedigrees of famous horses.

Seats in the Circus were free for the poor, who by the time of the Empire had little else to do, as they were no longer involved in political or military affairs as they had been in the Republic. The wealthy could pay for shaded seats where they had a better view, and they probably also spent much of their times betting on the races. The circus was the only place where the emperor showed himself before a populace assembled in vast numbers, and where the latter could manifest their affection or anger. The imperial box, called the pulvinar in the Circus Maximus, was directly connected to the imperial palace.[48]

The driver's clothing was color-coded in accordance with his faction, which would help distant spectators to keep track of the race's progress.[49] According to the disapproving Tertullian, there were originally just two factions, White and Red, sacred to winter and summer respectively.[50] As fully developed, there were four factions, the Red, White, Green, and Blue.[51] Each team could have up to three chariots each in a race. Members of the same team often collaborated with each other against the other teams, for example to force them to crash into the spina (a legal and encouraged tactic).[37] Drivers could switch teams, much like athletes can be traded to different teams today.

By 77 BC the rivalry between the Red and the Whites was already developed, when a funeral for a Red driver involved a Red supporter throwing himself on the funeral pyre. No writer of the time, however, refers to these as factions such as came into existence later, with the factions being official organizations.[37] Writing near the beginning of the third century, he wrote that the Reds were dedicated to Mars, the Whites to the Zephyrs, the Greens to Mother Earth or spring, and the Blues to the sky and sea or autumn.[50] Domitian created two new factions, the Purples and Golds, which disappeared soon after he died.[37] The Blues and the Greens gradually became the most prestigious factions, supported by emperor and populace alike. Indeed, Reds and Whites are only rarely mentioned in the surviving literature, although their continued activity is documented in inscriptions and in curse-tablets.[52]

Byzantine era

Like many other aspects of the Roman world, chariot racing continued in the Byzantine Empire, although the Byzantines did not keep as many records and statistics as the Romans did. Constantine I preferred chariot racing to gladiatorial combat, which he considered a vestige of paganism.[53] The Olympic Games were eventually ended by the emperor Theodosius I in 393, in a move to suppress paganism and promote Christianity, but chariot racing remained popular. The fact that chariot racing became linked to the imperial majesty meant that the Church did not prevent it, although gradually prominent Christian writers, such as Tertullian, began attacking the sport.[54] The Hippodrome of Constantinople (really a Roman circus, not the open space that the original Greek hippodromes were) was connected to the emperor's palace and the Church of Hagia Sophia, allowing spectators to view the emperor as they had in Rome.[55]

There is not much evidence that the chariot races were subject to bribes or other forms of cheating in the Roman Empire. In the Byzantine Empire there seems to have been more cheating; Justinian I's reformed legal code prohibits drivers from placing curses on their opponents, but otherwise there does not seem to have been any mechanical tampering or bribery. Wearing the colours of your team became an important aspect of Byzantine dress.

Chariot racing in the Byzantine Empire also included the Roman racing clubs, which continued to play a prominent role in these public exhibitions. By this time, the Blues (Vénetoi) and the Greens (Prásinoi) had come to overshadow the other two factions of the Whites (Leukoí) and Reds (Roúsioi), while still maintaining the paired alliances, although these were now fixed as Blue and White vs. Green and Red.[56] The Emperor himself belonged to one of the four factions, and supported the interests of either the Blues or the Greens.[57]

The Blues and the Greens were now more than simply sports teams. They gained influence in military, political,[58] and theological matters, although the hypothesis that the Greens tended towards Monophysitism and the Blues represented Orthodoxy is disputed. It is now widely believed that neither of the factions had any consistent religious bias or allegiance, in spite of the fact that they operated in an environment fraught with religious controversy.[59] According to some scholars, the Blue-Green rivalry contributed to the conditions that underlay the rise of Islam, while factional enmities were exploited by the Sassanid Empire in its conflicts with the Byzantines during the century preceding Islam's advent.[60]

The Blue-Green rivalry often erupted into gang warfare, and street violence had been on the rise in the reign of Justin I, who took measures to restore order, when the gangs murdered a citizen in Hagia Sophia.[61] Riots culminated in the Nika riots of 532 AD during the reign of Justinian, which began when the two main factions united and attempted unsuccessfully to overthrow the emperor.[62] Chariot racing seems to have declined in the course of the seventh century, with the losses the Empire suffered at the hands of the Arabs and the decline of the population and economy.[63] The Blues and Greens, deprived of any political power, were relegated to a purely ceremonial role. The Hippodrome in Constantinople remained in use for races, games and public ceremonies up to the sack of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. In the 12th century, Emperor Manuel I Komnenos even staged Western-style jousting matches in the Hippodrome. During the sack of 1204, the Crusaders looted the city and, among other things, removed the copper quadriga that stood above the carceres; it is now displayed at St. Mark's Cathedral in Venice.[64] Thereafter, the Hippodrome was neglected, although still occasionally used for spectacles. A print of the Hippodrome from the fifteenth century shows a derelict site, a few walls still standing, and the spina, the central reservation, robbed of its splendor. Today only the obelisks and the Serpent Column stand where for centuries the spectators gathered.[47] In the West, the games had ended much sooner; by the end of the fourth century public entertainments in Italy had come to an end in all but a few towns.[65] The last recorded chariot race in Rome itself took place in the Circus Maximus in 549 AD.[66]

References

- ↑ A number of fragments of pottery from show two or more chariots, obviously in the middle of a race. According to Bennett, this is a clear indication that chariot racing existed as a sport from as early as the thirteenth century BC. Chariot races are also depicted on late Geometric vases (Bennett, Chariot Racing, 41–48).

- ↑ Homer, The Iliad, 23, 257–652.

- ↑ Pindar, Olympian Odes, 1.75

* Bennett, Chariot Racing, 41–48 - ↑ Synoris succeeded tethrippon in 384 BC. Tethrippon was reintroduced in 268 BC (Valettas, Chariot Racing, 613).

- ↑ Polidoro, The Games of 676 BC, 41–46

* Valettas, Chariot Racing, 613 - ↑ Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece, 350, 420

- ↑ Little is known of the construction of hippodromes before the Roman period (Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece, 218–219).

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.20.10–19

* Vikatou, Hippodrome of Olympia - ↑ Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece, 420

- ↑ Golden, Sport in the Ancient World, 86

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.20.13

- ↑ Thucydides, 6.16.2

- ↑ Pindar, Isthmian Odes, I.1.1.

- ↑ Polidoro, The Games of 676 BC, 41–46

- ↑ Golden, Sport in the Ancient World, 46

- ↑ Kyle, Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, 172

- ↑ Valettas, Chariot Racing, 613

- ↑ One of them is Carrhotus who is praised by Pindar for keeping his chariot unscathed (Pindar, Pythian, 5.25-53). Unlike the majority of charioteers, Carrhotus was friend and brother-in-law of the man he drove for, Arcesilaus of Cyrene; so his success affirmed the success of the traditional aristocratic mode of organizing society (Nicholson, Aristocratic Victory Memorials, 116).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Golden, Sport in the Ancient World, 34

- ↑ Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece, 416

- ↑ Valettas, Chariot Racing, 614

- ↑ Gagarin, Antilochus' Strategy, 35-39

- ↑ Τhe returning athletes also gained various benefits in their native towns, like tax exemptions, free clothing and meals and even prize money (Bennett, Chariot Racing, 41–48).

- ↑ Camp, Horses and Horsemanship, 40

- ↑ "Apobates". Encyclopaedia "The Helios".

- ↑ Niels-Tracy, The Games at Athens, 25

- ↑ Kyle, Athletics in Ancient Athens, 189

- ↑ In Rome chariot racing constituted one of the two types of public games, the ludi circenses. The other type, ludi scaenici, consisted chiefly of theatrical performances (Balsdon, Life and Leisure, 248; Mus, Ludi Circenses).

- ↑ Golden, Sport in the Ancient World, 35

* Harris, Sport in Greece and Rome, 185 - ↑ Boatwright-Cargola-Talbert, The Romans, 383

* Scullard, Festival and Ceremonies, 177–78 - ↑ 31.0 31.1 Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, 141–42

- ↑ There were many other circuses throughout the Roman Empire. Circus of Maxentius, another major circus, was built at the beginning of the fourth century BC outside Rome, near the Via Appia. There were major circuses at Alexandria and Antioch, and Herod the Great built four circuses in Judaea. Archaeologists working on a housing development in Essex have unearthed what they believe to be the first Roman chariot-racing arena to be found in Britain (Prudames, Roman Chariot-Racing Arena Is First to Be Unearthed in Britain).

- ↑ Boatwright-Cargola-Talbert, The Romans, 383

- ↑ According to the tradition, the Circus probably dated back to the time of the Etruscans (Adkins, Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, 141–42; Boatwright-Cargola-Talbert, The Romans, 383).

- ↑ Kyle, Sport and Spectacle, 305

- ↑ Kyle, Sport and Spectacle, 306

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 Balsdon, Life and Leisure, 314–19

- ↑ Harris, Sport in Greece and Rome, 215

- ↑ Balsdon, Life and Leisure, 314–19

*Ramsay, A Manual of Roman Antiquities, 348 - ↑ Harris, Sport in Greece and Rome, 190

- ↑ Dodge, Amusing the Masses, 237

*Ramsay, A Manual of Roman Antiquities, 348 - ↑ Futrell, The Roman Games, 191

- ↑ Kyle, Sport and Spectacle, 304

- ↑ Harris, Sport in Greece and Rome, 224–25

* Laurence, Roman Pompeii, 71

* Potter, A Companion to the Roman Empire, 375 - ↑ Roman drivers steered using their body weight; with the reigns tied around their torsos, charioteers could lean from one side to the other to direct the horse's movement, keeping the hands free for the whip and such (Futrell, The Roman Games, 191–92; Köhne, Gladiators and Caesars, 92)

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Futrell, The Roman Games, 191–92

*Ramsay, A Manual of Roman Antiquities, 348 - ↑ 47.0 47.1 Bennett, Chariot Racing, 41–48

- ↑ Lançon, Rome in Late Antiquity, 144

- ↑ Futrell, The Roman Games, 192

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Tertullian, De Spectaculis, IX

- ↑ Adkins Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, 347

- ↑ Futrell, The Roman Games, 209

- ↑ Treadgold, History of the Byzantine State, 41

- ↑ Tertullian (De Spectaculis, xvi) and Cassiodorus called chariot racing an instrument of the Devil. Salvian criticized those who rushed into the circus in order to "feast their impure, adulterous gaze on shameful obscenities" (Olivová, Chariot Racing in the Ancient World, 86). Public spectacles were also attacked by John Chrysostom (Liebeschuetz, The Decline of the Roman City, 217–18).

- ↑ The Hippodrome was situated immediately to the west of the imperial palace, and there was a private passage from the palace to the emperor's box, the kathisma, where the emperor showed himself to his subjects. One of Justinian's first acts on becoming emperor was to rebuild the kathisma, making it loftier and more impressive (Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 16).

- ↑ One of the most famous charioteers, Porphyrius, was a member of both the Blues and the Greens at various times in 5th century.(Futrell, The Roman Games, 200)

- ↑ Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 16

* Hathaway, A Tale of Two Factions, 31 - ↑ At the root of the political power eventually gained by the factions was the fact that from the mid-fifth century the making of an emperor required that he should be acclaimed by the people (Liebeschuetz, The Decline of the Roman City, 211).

- ↑ Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 17

* Liebeschuetz, The Decline of the Roman City, 215 - ↑ Khosrau I erected an hippodrome near Ctesiphon, and supported the Greens in deliberate contrast to his enemy, Justinian, who favored the Blues (Hathaway, A Tale of Two Factions, 31).

- ↑ Evans, The Emperor Justinian, 17

- ↑ McComb, Sports in World History, 25

- ↑ Liebeschuetz, The Decline of the Roman City, 219

- ↑ Freeman, St Mark's Square, 39

- ↑ Liebeschuetz, The Decline of the Roman City, 219–20

- ↑ Balsdon, Life and Leisure, 252

Sources

Primary sources

Homer: Iliad on Wikisource

Homer: Iliad on Wikisource- Pausanias, Description of Greece, Book 6: Elis II.See original text in Perseus program.

- Pindar, Isthmian Odes - Ishmian 1. See original text in Perseus program.

- Pindar, Olympian Odes - Olympian 1. See original text in Perseus program.

- Pindar, Pythian Odes - Pythian 5. See original text in Perseus program.

Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War on Wikisource, Book 6.

Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War on Wikisource, Book 6.- Tertullian, De Spectaculis. See original text in the Latin library.

Secondary sources

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (1997). Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512491-X.

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (1994). Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512332-8.

- Camp, John Mck (1998). Horses and Horsemanship in the Athenian Agora. ASCSA. ISBN 0-876-61639-2.

- "Apobates". Encyclopedia "The Helios" III. (1945–1955).

- Bennett, Dirk (December 1997). "Chariot racing in the ancient world". History Today (Britain) 47 (12): 41–48. http://www.worldagesarchive.com/Reference_Links/Chariot_Racing_in_Antiquity.htm.

- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro; Gargola, Daniel J.; Talbert, Richard J. A. (2004). "Circuses and Chariot Racing". The Romans: From Village to Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11875-8.

- Dodge, Hazel (1999). "Amusing the Masses: Building for Entertainment and Leisure in the Roman World". in David Stone Potter, D. J. Mattingly. Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08568-9.

- Evans, James Allan Stewart (2005). "The Nika Revolt of 532". The Emperor Justinian and the Byzantine Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-32582-0.

- Finley, M. I. The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years. New York: Viking Press, 1976. ISBN 0-670-52406-9

- Freeman, Charles (April 2004). "St Mark's Square: an Imperial Hippodrome?". History Today (Britain: History Today Ltd) 54 (4): 39.

- Futrell, Alison (2006). The Roman Games: A Sourcebook. Blackwell. ISBN 1-405-11568-8.

- Gagarin, Michael (Januar 1983). "Antilochus' Strategy: The Chariot Race in Iliad 23". Classical Philology (Britain: The University of Chicago Press) 78 (1): 35–39. doi:. http://www.jstor.org/pss/269909.

- Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24881-7.

- Harris, Harold Arthur (1972). Sport in Greece and Rome. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-801-40718-4.

- Hathaway, Jane (2003). "Bilateral Factionalism in Ottoman Egypt". A Tale of Two Factions. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-791-45883-0.

- Köhne, Eckart; Cornelia Ewigleben (2000). Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome. British Museum Press. ISBN 9-7807-1412316-5.

- Kyle, Donald G. (1993). Athletics in Ancient Athens. BRILL. ISBN 9-004-09759-7.

- Kyle, Donald G. (2006). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. WileyBlackwell. ISBN 9-780-63122-971-1.

- Lançon, Bertrand (2000). "Festivals and Entertainments". Rome in Late Antiquity: Everyday Life and Urban Change, AD 312-609 (Translated by Antonia Nevil). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-92976-8.

- Liebeschuetz, John Hugo Wolfgang Gideon (2001). "Shows and Factions". The Decline and Fall of the Roman City. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-199-26109-1.

- McComb, David G. (2004). Sports in World History. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31811-4.

- Mus, P. Dionysius. "Ludi Circenses (longer version)". Societas via Romana. Retrieved on 2008-04-05.

- Neils, Jenifer; Tracy, Stephen V. (2003). Games at Athens. ASCSA. ISBN 0-876-61641-4.

- Nicholson, Nigel (2003). "Aristocratic Victory Memorials and the Absent Charioteer". in Carol Dougherty and Leslie Kurke. The Cultures Within Ancient Greek Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81566-5.

- Olivová, Věra (1989). "Chariot Racing in the Ancient World". Nikephoros - Zeitschrift für Sport und Kultur im Altertum (Georg Olms Verlag) 2: 65–88. ISBN 3-615-00058-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=uw98TdMu3tQC&dq=Byzantine,+chariot+racing&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0.

- Polidoro, J. Richard; Uriel Simri (May – June 1996). "The Games of 676 BC: a Visit to the Centenary of the Ancient Olympic Games". The Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance (American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance) 67 (5): 41–46.

- Prudames, David (2008-01-05). "Roman Chariot-Racing Arena Is First to Be Unearthed in Britain", 24 Hour Museum. Retrieved on 2008-04-05.

- Ramsay, William Wardlaw (1863). "Games of the Circus". A Manual of Roman Antiquities. Oxford University.

- Scullard, H. H. (1981). Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1402-4.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). "Refoundation of Empire". Games at Athens. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Valettas, G.M. (1945–1955). "Chariot Racing". Encyclopedia "The Helios" III. Ed. Passas Ioannis.

- Vikatou, Olympia. "Hippodrome of Olympia – Description". Hellenic World Heritage Monuments. Hellenic Ministry of Culture. Retrieved on 2008-03-22.

External links

- BBC - h2g2 - Chariot Racing. BBC - bbc.co.uk homepage - Home of the BBC on the Internet: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

- Byzantine Chariot racing. Formula 1|Chariot Racing.

- Chariot Races. United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History - Roman Empire.

- Chariot Racing. VRoma: A Virtual Community for Teaching and Learning Classics.

- The Games: Chariot Racing. The Roman Empire.

- Greek Chariot Racing. Formula 1|Chariot Racing.

- Roman Army and Chariot Racing. The Roman Army and Chariot Experience (RACE) Jerash Jordan.

- Roman Chariot Racing. Formula 1|Chariot Racing.