Forward (association football)

Forwards, also known as attackers and strikers, are the players on a team in association football in the row nearest to the opposing team's goal, who are therefore principally responsible for scoring goals. This very advanced position and its limited defensive responsibilities mean forwards normally score more goals than other players; accordingly, they are often among the best-known and most expensive players in their teams.

Modern team formations usually include one to three forwards; two is most common. Coaches typically field one striker who plays in an advanced position, and another attacking forward who plays somewhat deeper and assists in making goals as well as scoring.

The former is often a tall player, typically known as a target man, who is used to win long balls or receive passes and "hold up" the ball as team-mates advance, to help team-mates score by providing a pass ('through ball' into the box), or to score himself; the latter variation usually requiring quicker pace. Some forwards operate on the wings of the field and work their way goalward.

Contents |

Centre forward or Striker

The centre forward, or an "out-and-out" striker, is normally the principal goal-scorer of a football team. Centre forwards act predominantly as the focal point of an attack; it is the duty of the midfield to supply and to assist them to score. The name "centre forward" comes from the old 2-3-5 formation, where teams played five attackers: two outside forwards, two inside forwards and one centre forward. Formations developed to (often) include two central forwards, or "strikers", with the outside forwards becoming "wingers".

Some strikers are goal poachers who tend to stay forward at all times and work in and around the penalty area to snatch goals, and are sometimes referred to proverbially as a "fox in the box". These players are known for their positional sense, excellent reflexes and finishing ability.

Others may rely on their pace to latch on balls from outside the six-yard area, playing 'over the shoulder' of the last defender and trying to beat the offside trap.[1]

Some rely on their technical skills to create their own goalscoring opportunities, displaying excellent close control and dribbling ability to pierce through opposition defences.

Another type are known as "target men" and are usually of above-average height, with good heading ability. They hold the ball up and bring other players into the game, using their body strength to shield the ball while turning to score, and often scoring with the head from crosses. A target man might be asked to play without a strike partner, as a lone forward. Due to their aerial ability, these players are also often called upon to assist the defence when the opposition have a corner, or a free-kick in an advanced position.

A top striker may have the attributes to perform more than one of these roles.

Second striker

Deep-lying forwards have a long history in the game, but the terminology to describe them has varied over the years. Originally such players were termed inside forwards, or deep-lying centre forwards. More recently, two more variations of this old type of player have developed: the second or support or auxiliary striker and, in what is arguably a distinct position unto its own, being neither midfield nor attack, the Number 10, or playmaker, an advanced as opposed to a deep-lying playmaker.

The second striker position is a loosely-defined and often misapplied one somewhere between the out-and-out striker, whether he is a target-man or more of a poacher, and the Number 10 or Trequartista, while possibly showing some of the characteristics of both. In fact, a coined term, the "nine-and-a-half", has been an attempt to define the position. Conceivably, a Number 10 can alternate as a second-striker provided that he is also a prolific goalscorer, otherwise a striker (such as Del Piero or Raúl) who can both score and create opportunities for a less versatile centre forward is more suited. This has been true of a natural trequartista like Roberto Baggio who seldom played in a team formation which permitted him the creative license to play as a number 10 and so he adapted himself to the second-striker role. A second- or support-striker does not tend to get as involved in the orchestration of attacks, nor bring as many other players into play as the Number 10 since they do not have the range of vision, nor the burden of responsibility that the latter, around whom the team's game is built, possess. Accordingly, neither do they have as much responsibility for inventing the game.[2]

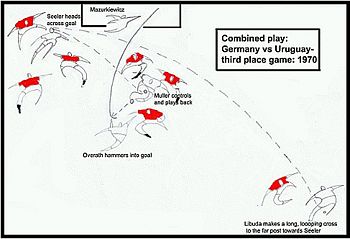

Successful attacks require the collaboration of many strikers, and goals can be made from the flanks or from the centre, all in one movement. In the diagram shown, some of the most successful strikers of the 20th century help to create a goal for a midfielder. The fast German winger Libuda starts the move by floating a long cross to Seeler at the far post. Seeler heads down for Muller, who plays it back to midfielder Overath for a goal. Though considered a centre-forward, Seeler's dangerous aerial skills created countless chances for his team-mates. Skilful combined play will see a centre-forward switch to a supporting role as the situation demands.

Winger

A winger is an attacking player who is stationed in a wide position near the touchlines. They can be classified as forwards, considering their origin as the old "outside-forward" position, and continue to be termed as such in most parts of the world, especially in Latin and Dutch footballing cultures. However, in the Anglo-Saxon world, they are usually counted as part of the midfield.

It is a winger's duty to beat opposing fullbacks, deliver cut-backs or crosses from wide positions and, to a lesser extent, to beat defenders and score from close range They are usually some of the quickest players in the team and usually have good dribbling skills as well. In their Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese usage, the defensive duties of the winger have been usually confined to pressing the opposition fullbacks when they have the ball. Otherwise, a winger will drop closer to the midfield to make himself available, should his team win back the ball.

In British and other northern European styles of football, the wide-midfielder is expected to track back all the way to his own corner flag should his full-back require help, as well as tucking into the midfield when the more central players are trying to pressure the opposition for the ball, a huge responsibility for attack-orientated players, and particularly those like Joaquin (winger/wide midfielder) or Leo Messi (winger/second-striker) that lack the physical attributes of a wing-back or of a more orthodox midfield player. As these players grow older and lose their natural pace, they are frequently redeployed as Number 10s between the midfield and the forward line, where their innate ball control and improved reading of the game in the final third can serve to improve their teams' attacking options in tight spaces. An example is Internazionale use of veteran Luis Figo behind one or two other attackers.[3]

In recent years there has been a trend of playing 'unorthodox' wingers - wide men stationed on the 'wrong' side of the pitch, in order to enable them to cut inside and shoot on their stronger foot. One example of this is the tactical use of Robin van Persie by Netherlands coach Marco van Basten at the 2006 World Cup; the Netherlands played with a front three of Arjen Robben wide left, target-man Ruud van Nistelrooy in the middle and the left-footed van Persie wide right. Such deployment usually leads to players being referred to as playing 'from the right' rather than 'on the right'. Similarly, former Newcastle United manager Sam Allardyce, who favours a front three, started the 2007-08 season with right-footed James Milner playing from the left, Mark Viduka as a centre forward and left-footed Obafemi Martins from the right, whilst at Manchester United it is common for right-footed Cristiano Ronaldo and left-footed Ryan Giggs to switch sides continually throughout a match.

In the 1970s, one of the foremost practitioners of playing from either flank was the German winger, Jürgen Grabowski, whose flexibility helped Germany to third place in 1970, and a championship in 1974.

Strike teams and combinations

A strike team is two or more strikers that work well together to devastating effect. The history of football is filled with such effective combinations. Two-player partnerships such as Dwight Yorke and Andy Cole of the 1999 Manchester United treble winning squad, are well known, but also important to any attack are bigger groups of players who form distinct strike packages. Three-man teams often operate in "triangles", giving a wealth of attacking options. Four-man packages expand options even more.

Whatever the number of players involved, the strikers must possess good technical skills, be creative and have a hunger for goal. Strikers must also be flexible, and be able to switch roles at a moment's notice, between the first (advanced penetrator position), second (deep-lying manoeuvre) and third (support and expansion, eg. wings) attacker roles.

Depicted is an illustration of strikers at work, from one of the most potent strike teams of the 20th century - Pelé, Jairzinho and Tostão of Brazil. During Brazil's 1970 campaign, centre-forward Tostão played the advanced penetration role of first attacker as described above in the article. Pelé often dropped back into midfield not only to escape tight marking but to draw his markers with him, opening gaps and helping create attacks. The third attacker- the winger Jairzinho, often took an advanced position but specialized in working the right side of the field.

In the semi-final against the ultra-defensive Uruguay, it is Pelé who takes on the role of target man, dropping infield to receive from Jairzinho. Tostão becomes the second attacker and Pelé finds him with a soft back-heel. Jairzinho meanwhile becomes the most advanced man, sprinting far upfield to receive Tostão's pass. This tight exchange put Jair through for a score, and illustrates how three strikers can work together to blow open the tightest defences.

Another example was the Total Football played by the Dutch team in the 1970s, where the ability of their players, and in particular Johan Cruijff, to swap positions allowed a flexible attacking approach which opposition teams found difficult to effectively mark.

See also

- Association football positions

- Formation (association football)

- Long ball

- Goalkeepers