Cell (biology)

The cell is the structural and functional unit of all known living organisms. It is the smallest unit of an organism that is classified as living, and is often called the building block of life.[1] Some organisms, such as most bacteria, are unicellular (consist of a single cell). Other organisms, such as humans, are multicellular. (Humans have an estimated 100 trillion or 1014 cells; a typical cell size is 10 µm; a typical cell mass is 1 nanogram.) The largest known cell is an unfertilized ostrich egg cell.

In 1837 before the final cell theory was developed, a Czech Jan Evangelista Purkyně observed small "granules" while looking at the plant tissue through a microscope. The cell theory, first developed in 1839 by Matthias Jakob Schleiden and Theodor Schwann, states that all organisms are composed of one or more cells. All cells come from preexisting cells. Vital functions of an organism occur within cells, and all cells contain the hereditary information necessary for regulating cell functions and for transmitting information to the next generation of cells.[2]

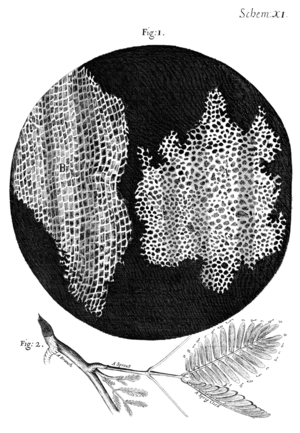

The word cell comes from the Latin cellula, meaning, a small room. The descriptive name for the smallest living biological structure was chosen by Robert Hooke in a book he published in 1665 when he compared the cork cells he saw through his microscope to the small rooms monks lived in.[3]

Contents |

General principles

Each cell is at least somewhat self-contained and self-maintaining: it can take in nutrients, convert these nutrients into energy, carry out specialized functions, and reproduce as necessary. Each cell stores its own set of instructions for carrying out each of these activities.

All cells have several different abilities:[4]

- Reproduction by cell division: (binary fission/mitosis or meiosis).

- Use of enzymes and other proteins coded for by DNA genes and made via messenger RNA intermediates and ribosomes.

- Metabolism, including taking in raw materials, building cell components, converting energy, molecules and releasing by-products. The functioning of a cell depends upon its ability to extract and use chemical energy stored in organic molecules. This energy is released and then used in metabolic pathways.

- Response to external and internal stimuli such as changes in temperature, pH or levels of nutrients.

- Cell contents are contained within a cell surface membrane that is made from a lipid bilayer with proteins embedded in it.

Some prokaryotic cells contain important internal membrane-bound compartments,[5] but eukaryotic cells have a specialized set of internal membrane compartments.

Anatomy of cells

There are two types of cells: eukaryotic and prokaryotic. Prokaryotic cells are usually independent, while eukaryotic cells are often found in multicellular organisms.

Prokaryotic cells

Prokaryotes differ from eukaryotes since they lack a nuclear envelope and a cell nucleus. Prokaryotes also lack most of the intracellular organelles and structures that are seen in eukaryotic cells. There are two kinds of prokaryotes, bacteria and archaea, but these are similar in the overall structures of their cells. Most functions of organelles, such as mitochondria, chloroplasts, and the Golgi apparatus, are taken over by the prokaryotic cell's plasma membrane. Prokaryotic cells have three architectural regions: appendages called flagella and pili — proteins attached to the cell surface; a cell envelope - consisting of a capsule, a cell wall, and a plasma membrane; and a cytoplasmic region that contains the cell genome (DNA) and ribosomes and various sorts of inclusions. Other features include:

- The plasma membrane (a phospholipid bilayer) separates the interior of the cell from its environment and serves as a filter and communications beacon.

- Most prokaryotes have a cell wall (some exceptions are Mycoplasma (bacteria) and Thermoplasma (archaea)). This wall consists of peptidoglycan in bacteria, and acts as an additional barrier against exterior forces. It also prevents the cell from expanding and finally bursting (cytolysis) from osmotic pressure against a hypotonic environment. A cell wall is also present in some eukaryotes like plants (cellulose) and fungi, but has a different chemical composition.

- A prokaryotic chromosome is usually a circular molecule (an exception is that of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease). Even without a real nucleus, the DNA is condensed in a nucleoid. Prokaryotes can carry extrachromosomal DNA elements called plasmids, which are usually circular. Plasmids can carry additional functions, such as antibiotic resistance.

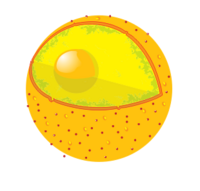

Eukaryotic cells

Organelles:

(1) nucleolus

(2) nucleus

(3) ribosome

(4) vesicle

(5) rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

(6) Golgi apparatus

(7) Cytoskeleton

(8) smooth endoplasmic reticulum

(9) mitochondria

(10) vacuole

(11) cytoplasm

(12) lysosome

(13) centrioles within centrosome

Eukaryotic cells are about 10 times the size of a typical prokaryote and can be as much as 1000 times greater in volume. The major difference between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is that eukaryotic cells contain membrane-bound compartments in which specific metabolic activities take place. Most important among these is the presence of a cell nucleus, a membrane-delineated compartment that houses the eukaryotic cell's DNA. It is this nucleus that gives the eukaryote its name, which means "true nucleus." Other differences include:

- The plasma membrane resembles that of prokaryotes in function, with minor differences in the setup. Cell walls may or may not be present.

- The eukaryotic DNA is organized in one or more linear molecules, called chromosomes, which are associated with histone proteins. All chromosomal DNA is stored in the cell nucleus, separated from the cytoplasm by a membrane. Some eukaryotic organelles such as mitochondria also contain some DNA.

- Eukaryotes can move using cilia or flagella. The flagella are more complex than those of prokaryotes.

| Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes | |

|---|---|---|

| Typical organisms | bacteria, archaea | protists, fungi, plants, animals |

| Typical size | ~ 1-10 µm | ~ 10-100 µm (sperm cells, apart from the tail, are smaller) |

| Type of nucleus | nucleoid region; no real nucleus | real nucleus with double membrane |

| DNA | circular (usually) | linear molecules (chromosomes) with histone proteins |

| RNA-/protein-synthesis | coupled in cytoplasm | RNA-synthesis inside the nucleus protein synthesis in cytoplasm |

| Ribosomes | 50S+30S | 60S+40S |

| Cytoplasmatic structure | very few structures | highly structured by endomembranes and a cytoskeleton |

| Cell movement | flagella made of flagellin | flagella and cilia containing microtubules; lamellipodia and filopodia containing actin |

| Mitochondria | none | one to several thousand (though some lack mitochondria) |

| Chloroplasts | none | in algae and plants |

| Organization | usually single cells | single cells, colonies, higher multicellular organisms with specialized cells |

| Cell division | Binary fission (simple division) | Mitosis (fission or budding) Meiosis |

| Typical animal cell | Typical plant cell | |

|---|---|---|

| Organelles |

|

|

| Additional structures |

|

|

Subcellular components

All cells, whether prokaryotic or eukaryotic, have a membrane that envelops the cell, separates its interior from its environment, regulates what moves in and out (selectively permeable), and maintains the electric potential of the cell. Inside the membrane, a salty cytoplasm takes up most of the cell volume. All cells possess DNA, the hereditary material of genes, and RNA, containing the information necessary to build various proteins such as enzymes, the cell's primary machinery. There are also other kinds of biomolecules in cells. This article will list these primary components of the cell, then briefly describe their function.

Cell membrane: A cell's defining boundary

The cytoplasm of a cell is surrounded by a cell membrane or plasma membrane. The plasma membrane in plants and prokaryotes is usually covered by a cell wall. This membrane serves to separate and protect a cell from its surrounding environment and is made mostly from a double layer of lipids (hydrophobic fat-like molecules) and hydrophilic phosphorus molecules. Hence, the layer is called a phospholipid bilayer. It may also be called a fluid mosaic membrane. Embedded within this membrane is a variety of protein molecules that act as channels and pumps that move different molecules into and out of the cell. The membrane is said to be 'semi-permeable', in that it can either let a substance (molecule or ion) pass through freely, pass through to a limited extent or not pass through at all. Cell surface membranes also contain receptor proteins that allow cells to detect external signalling molecules such as hormones.

Cytoskeleton: A cell's scaffold

The cytoskeleton acts to organize and maintain the cell's shape; anchors organelles in place; helps during endocytosis, the uptake of external materials by a cell, and cytokinesis, the separation of daughter cells after cell division; and moves parts of the cell in processes of growth and mobility. The eukaryotic cytoskeleton is composed of microfilaments, intermediate filaments and microtubules. There is a great number of proteins associated with them, each controlling a cell's structure by directing, bundling, and aligning filaments. The prokaryotic cytoskeleton is less well-studied but is involved in the maintenance of cell shape, polarity and cytokinesis.[6]

Genetic material

Two different kinds of genetic material exist: deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA). Most organisms use DNA for their long-term information storage, but some viruses (e.g., retroviruses) have RNA as their genetic material. The biological information contained in an organism is encoded in its DNA or RNA sequence. RNA is also used for information transport (e.g., mRNA) and enzymatic functions (e.g., ribosomal RNA) in organisms that use DNA for the genetic code itself. Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules are used to add specific amino acids during the process of protein translation.

Prokaryotic genetic material is organized in a simple circular DNA molecule (the bacterial chromosome) in the nucleoid region of the cytoplasm. Eukaryotic genetic material is divided into different, linear molecules called chromosomes inside a discrete nucleus, usually with additional genetic material in some organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts (see endosymbiotic theory).

A human cell has genetic material in the nucleus (the nuclear genome) and in the mitochondria (the mitochondrial genome). In humans the nuclear genome is divided into 23 pairs of linear DNA molecules called chromosomes. The mitochondrial genome is a circular DNA molecule distinct from the nuclear DNA. Although the mitochondrial DNA is very small compared to nuclear chromosomes, it codes for 13 proteins involved in mitochondrial energy production as well as specific tRNAs.

Foreign genetic material (most commonly DNA) can also be artificially introduced into the cell by a process called transfection. This can be transient, if the DNA is not inserted into the cell's genome, or stable, if it is. Certain viruses also insert their genetic material into the genome.

Organelles

The human body contains many different organs, such as the heart, lung, and kidney, with each organ performing a different function. Cells also have a set of "little organs," called organelles, that are adapted and/or specialized for carrying out one or more vital functions.

There are several types of organelles within an animal cell. Some (such as the nucleus and golgi apparatus) are typically solitary, while others (such as mitochondria, peroxisomes and lysosomes) can be numerous (hundreds to thousands). The cytosol is the gelatinous fluid that fills the cell and surrounds the organelles.

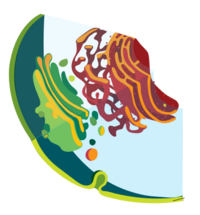

- Mitochondria and Chloroplasts (the power generators)

- Mitochondria are self-replicating organelles that occur in various numbers, shapes, and sizes in the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells. Mitochondria play a critical role in generating energy in the eukaryotic cell. Mitochondria generate the cell's energy by the process of oxidative phosphorylation, utilizing oxygen to release energy stored in cellular nutrients (typically pertaining to glucose) to generate ATP. Mitochondria multiply by splitting in two.

- Organelles that are modified chloroplasts are broadly called plastids, and are involved in energy storage through the process of photosynthesis, which utilizes solar energy to generate carbohydrates and oxygen from carbon dioxide and water.

- Mitochondria and chloroplasts each contain their own genome, which is separate and distinct from the nuclear genome of a cell. Both of these organelles contain this DNA in circular plasmids, much like prokaryotic cells, strongly supporting the evolutionary theory of endosymbiosis; since these organelles contain their own genomes and have other similarities to prokaryotes, they are thought to have developed through a symbiotic relationship after being engulfed by a primitive cell.

- Ribosomes

- The ribosome is a large complex of RNA and protein molecules. This is where proteins are produced. Ribosomes can be found either foating freely or bound to a membrane (the rough endoplasmatic reticulum in eukaryotes, or the cell membrane in prokaryotes).[7]

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Structures outside the cell wallCapsuleIt is present only in some bacteria outside the cell wall. It is gelatinous in nature. The capsule may be polysaccharide as in pneumococci, meningococci or polypeptide as bacillus anthracis or hyaluronic acid as in streptococci. Capsules not stained by ordinary stain and can detected by special stain. The capsule is antigenic. The capsule has antiphagocytic function so it determines the virulence of many bacteria. It also plays a role in attachment of the organism to mucous membranes. FlagellaFlagella are the organelles of mobility. They arise from cytoplasm and extrude through the cell wall. They are long and thick thread like appendages, protein in nature, formed of flagellin protein (antigenic). They can not be stained by gram stain. They have a special stain. According to their arrangement they may be monotrichate, amphitrichate, lophotrichate, peritrichate. Fimbriae (pili)They are short and thin hair like filaments, formed of protein called pilin (antigenic). Fimbriae are responsible for attachement of bacteria to specific receptors of human cell (adherence). There are special types of pili called (sex pili) involved in the process of conjunction. Cell functionsCell growth and metabolismBetween successive cell divisions, cells grow through the functioning of cellular metabolism. Cell metabolism is the process by which individual cells process nutrient molecules. Metabolism has two distinct divisions: catabolism, in which the cell breaks down complex molecules to produce energy and reducing power, and anabolism, in which the cell uses energy and reducing power to construct complex molecules and perform other biological functions. Complex sugars consumed by the organism can be broken down into a less chemically-complex sugar molecule called glucose. Once inside the cell, glucose is broken down to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a form of energy, via two different pathways. The first pathway, glycolysis, requires no oxygen and is referred to as anaerobic metabolism. Each reaction is designed to produce some hydrogen ions that can then be used to make energy packets (ATP). In prokaryotes, glycolysis is the only method used for converting energy. The second pathway, called the Krebs cycle, or citric acid cycle, occurs inside the mitochondria and is capable of generating enough ATP to run all the cell functions.

An overview of protein synthesis.

Within the nucleus of the cell (light blue), genes (DNA, dark blue) are transcribed into RNA. This RNA is then subject to post-transcriptional modification and control, resulting in a mature mRNA (red) that is then transported out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm (peach), where it undergoes translation into a protein. mRNA is translated by ribosomes (purple) that match the three-base codons of the mRNA to the three-base anti-codons of the appropriate tRNA. Newly-synthesized proteins (black) are often further modified, such as by binding to an effector molecule (orange), to become fully active. Creation of new cellsCell division involves a single cell (called a mother cell) dividing into two daughter cells. This leads to growth in multicellular organisms (the growth of tissue) and to procreation (vegetative reproduction) in unicellular organisms. Prokaryotic cells divide by binary fission. Eukaryotic cells usually undergo a process of nuclear division, called mitosis, followed by division of the cell, called cytokinesis. A diploid cell may also undergo meiosis to produce haploid cells, usually four. Haploid cells serve as gametes in multicellular organisms, fusing to form new diploid cells. DNA replication, or the process of duplicating a cell's genome, is required every time a cell divides. Replication, like all cellular activities, requires specialized proteins for carrying out the job. Protein synthesisCells are capable of synthesizing new proteins, which are essential for the modulation and maintenance of cellular activities. This process involves the formation of new protein molecules from amino acid building blocks based on information encoded in DNA/RNA. Protein synthesis generally consists of two major steps: transcription and translation. Transcription is the process where genetic information in DNA is used to produce a complementary RNA strand. This RNA strand is then processed to give messenger RNA (mRNA), which is free to migrate through the cell. mRNA molecules bind to protein-RNA complexes called ribosomes located in the cytosol, where they are translated into polypeptide sequences. The ribosome mediates the formation of a polypeptide sequence based on the mRNA sequence. The mRNA sequence directly relates to the polypeptide sequence by binding to transfer RNA (tRNA) adapter molecules in binding pockets within the ribosome. The new polypeptide then folds into a functional three-dimensional protein molecule. Cell movement or motilityCells can move during many processes: such as wound healing, the immune response and cancer metastasis. For wound healing to occur, white blood cells and cells that ingest bacteria move to the wound site to kill the microorganisms that cause infection. At the same time fibroblasts (connective tissue cells) move there to remodel damaged structures. In the case of tumor development, cells from a primary tumor move away and spread to other parts of the body. Cell motility involves many receptors, crosslinking, bundling, binding, adhesion, motor and other proteins.[8] The process is divided into three steps - protrusion of the leading edge of the cell, adhesion of the leading edge and deadhesion at the cell body and rear, and cytoskeletal contraction to pull the cell forward. Each of these steps is driven by physical forces generated by unique segments of the cytoskeleton.[9][10] EvolutionThe origin of cells has to do with the origin of life, which began the history of life on Earth. Origin of the first cell

There are three leading hypotheses for the source of small molecules that would make up life in an early Earth. One is that they came from meteorites (see Murchison meteorite). Another is that they were created at deep-sea vents. A third is that they were synthesized by lightning in a reducing atmosphere (see Miller–Urey experiment), although it is not sure Earth had such an atmosphere. There is essentially no experimental data to tell what the first self-replicate forms were. RNA is generally assumed to be the earliest self-replicating molecule, as it is capable of both storing genetic information and catalyze chemical reactions (see RNA world hypothesis). But some other entity with the potential to self-replicate could have preceded RNA, like clay or peptide nucleic acid.[11] Cells emerged at least 3.0–3.3 billion years ago. An important character of cells is the cell membrane, composed of a bilayer of lipids. The early cell membranes were probably more simple and permeable than modern ones, with only a single fatty acid chain per lipid. Lipids are known to spontaneously form bilayered vesicles in water, and could have preceded RNA. But the first cell membranes could also have been produced by catalytic RNA, or even have required structural proteins before they could form.[12] Origin of eukaryotic cellsThe eukaryotic cell seems to have evolved from a symbiotic community of prokaryotic cells. It is almost certain that DNA-bearing organelles like the mitochondria and the chloroplasts are what remains of ancient symbiotic oxygen-breathing proteobacteria and cyanobacteria, respectively, where the rest of the cell seems to be derived from an ancestral archaean prokaryote cell – a theory termed the endosymbiotic theory. There is still considerable debate about whether organelles like the hydrogenosome predated the origin of mitochondria, or viceversa: see the hydrogen hypothesis for the origin of eukaryotic cells. Sex, as the stereotyped choreography of meiosis and syngamy that persists in nearly all extant eukaryotes, may have played a role in the transition from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. An 'origin of sex as vaccination' theory suggests that the eukaryote genome accreted from prokaryan parasite genomes in numerous rounds of lateral gene transfer. Sex-as-syngamy (fusion sex) arose when infected hosts began swapping nuclearized genomes containing coevolved, vertically transmitted symbionts that conveyed protection against horizontal infection by more virulent symbionts.[13] History

See also

References

External links

Online textbooks

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||