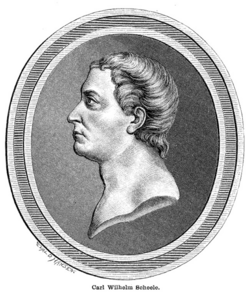

Carl Wilhelm Scheele

| Carl Wilhelm Scheele | |

Carl Scheele

|

|

| Born | 9 December 1742 Stralsund, Swedish Pomerania |

|---|---|

| Died | 21 May 1786 (aged 43) |

| Nationality | Swedish |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Known for | discover of oxygen, molybdenum and chlorine |

Carl Wilhelm Scheele (9 December 1742 – 21 May 1786) was a German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist, born in Stralsund, Western Pomerania, Germany (at the time under Swedish rule). He was the discoverer of many chemical substances, most notably discovering oxygen (although Joseph Priestley published his findings first), molybdenum and chlorine before Humphry Davy.

Contents |

Biography

Instead of becoming a carpenter like his father, Scheele decided to become a pharmacist. His career as a pharmacist began with his apprenticeship at an apothecary in Gothenburg when he was only fourteen years old. He retained this position for eight years before becoming an apothecary's clerk in Malmö. Then Scheele worked as a pharmacist in Stockholm, from 1770-1775 in Uppsala, and later in Köping. In 1776, he was able to establish his own pharmacy, which he had purchased from the previous owner's widow. The two married, but Scheele passed away 48 hours later.

Scientific career

Despite his lack of a thorough education, he clearly had an instinctive flair for experimentation. Scheele's limited formal instruction makes his successes all the more surprising. The schooling which Scheele did have was private and it was through this education that he exhibited an inclination to study the art of the pharmacist. He put substantial effort into learning as much as he could in science, even staying up late at night reading different chemical books.

Unlike scientists such as Antoine Lavoisier and Isaac Newton who were more widely recognized, Scheele had a humble position in a small town, and preferred that to the grandeur of an extravagant house, yet he was still able to make significant scientific discoveries. Scheele turned down high-paying offers by prestigious European academies. Frederick II offered him a Berlin position, and the English government offered him a generous salary for his work, but Scheele remained at his pharmacy to serve his faithful customers.

Scheele made many discoveries in chemistry before others who are generally given the credit. One of Scheele's most famous discoveries was oxygen produced as a by-product in a number of experiments in which he heated chemicals during 1771-1772. Scheele, though, did not name or define oxygen; that job would fall to Antoine Lavoisier, the second to quantitatively isolate the gas, (August 1774), who published a paper with the new name in 1775.

Scheele described the discovery of oxygen and nitrogen (1772-1773), in his only book, Chemische Abhandlung von der Luft und dem Feuer (Chemical Treatise on Air and Fire) in 1777, losing some fame to Joseph Priestley, who independently discovered oxygen in 1774. In his book, he also distinguished heat transfer by thermal radiation from that by convection or conduction. Like many other chemists of his time, Scheele often worked under difficult and even dangerous conditions. Also, he had a habit of tasting chemicals that he found. It appears that this was the cause of his premature death at the age of 43; his death symptoms resemble mercury poisoning. (Scheele also discovered an element called Molybdenum (Mo), which is now number 42 on the Periodic Table of the Elements. He discovered it in Köping, Sweden.)

The possibly apocryphal story is told that Scheele was to be ennobled by Gustavus III for his discoveries, but that the honor was mistakenly conferred on an obscure soldier of the same name (Fuller's Thesaurus of Anecdotes, 1116).

Existing theories before Scheele

By the time he was a teenager, Scheele had learned the dominant theory on gases in the 1770s, the phlogiston theory. Phlogiston, classified as "matter of fire" stated that any material that was able to burn would release phlogiston during combustion, and stops when all the phlogiston had been released. When Scheele discovered oxygen he called it "fire air" because it supported combustion, but he explained oxygen using phlogistical terms because he did not believe that his discovery disproved the phlogiston theory. Before Scheele made his discovery of oxygen, he studied air. Air was thought to be an element that made up the environment in which chemical reactions took place but did not interfere with the reactions. Scheele's investigation of air enabled him to conclude that air was a mixture of "fire air" and "foul air;" in other words, a mixture of two gases. He performed numerous experiments in which he burned substances such as saltpeter (potassium nitrate), manganese dioxide, heavy metal nitrates, silver carbonate and mercuric oxide. In all of these experiments, he isolated gas with the same properties; his "fire air," which he believed combined with phlogiston to be released during heat-releasing reactions. However, his first publication , A Chemical Treatise on Air and Fire, was not released until 1777 at which time both Joseph Priestley and Lavoisier had already published their experimental data and conclusions concerning oxygen and the phlogiston theory.

Debunking the theory of phlogiston

Historians of science no longer question the role of Carl Scheele in the overturning of the phlogiston theory. It is generally accepted that he was the first to discover oxygen, among a number of prominent scientists (namely his esteemed colleagues Antoine Lavoisier, Joseph Black, and Joseph Priestley). In fact, it was determined that Scheele made the discovery three years prior to Priestley and at least several before Lavoisier. Joseph Priestley relied heavily on Scheele's work, perhaps so much so that he would not have made the discovery of oxygen on his own. Correspondence between Lavoisier and Scheele indicate that Scheele achieved interesting results without the advanced laboratory equipment that Lavoisier was accustomed to. Through the studies of Lavoisier, Joseph Priestley, Scheele, and others, chemistry was made a standardized field with consistent procedures. Although Scheele was unable to grasp the significance of his discovery of oxygen, his work was essential for the invalidation of the long-held theory of phlogiston.

Scheele's study of the gas not yet named oxygen was sparked by a complaint by Torbern Olof Bergman. Bergman informed Scheele that the saltpeter he purchased from Scheele's employer produced red vapors when it came into contact with acid. Scheele's quick explanation for the vapors led Bergman to suggest that Scheele analyze the properties of manganese dioxide. It was through his studies with manganese dioxide that Scheele developed his concept of "fire air." He ultimately obtained oxygen by heating mercuric oxide, silver carbonate, magnesium nitrate, and saltpeter. Scheele wrote about his findings to Lavoisier who was able to grasp the significance of the results.

New elements

In addition to his joint recognition for the discovery of oxygen, Scheele is argued to have been the first to discover other chemical elements such as barium (1774), manganese (1774), molybdenum (1778), and tungsten (1781), as well as several chemical compounds, including citric acid, lactic acid, glycerol, hydrogen cyanide (also known, in aqueous solution, as prussic acid), hydrogen fluoride, and hydrogen sulfide. In addition, he discovered a process similar to pasteurization, along with a means of mass-producing phosphorus (1769), leading Sweden to become one of the world's leading producers of matches.

Scheele made one other very important scientific discovery in 1774, arguably more revolutionary than his isolation of oxygen. He identified lime, silica, and iron, in a specimen of pyrolusite given to him by his friend, Johann Gottlieb Gahn, but could not identify an additional component. When he treated the pyrolusite with hydrochloric acid over a warm sand bath, a yellow-green gas with a strong odor was produced. He found that the gas sank to the bottom of an open bottle and was denser than ordinary air. He also noted that the gas was not soluble in water. It turned corks a yellow color and removed all color from wet, blue litmus paper and some flowers. He called this gas with bleaching abilities, "dephlogisticated marine acid" (dephlogisticated hydrochloric acid). Eventually, Sir Humphrey Davy named the gas chlorine.

See also

- Scheelite

- Scheele's Green

- Pharmacist

- Pharmacy

- Pneumatic chemistry

- List of independent discoveries

References

- Abbott, David. (1983). Biographical Dictionary of Scientists: Chemists. New York: Peter Bedrick Books. pp. 126-127.

- Bell, Madison S. (2005). Lavoisier in the Year One. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Cardwell, D.S.L. (1971). From Watt to Clausius: The Rise of Thermodynamics in the Early Industrial Age. Heinemann: London. pp. 60-61. ISBN 0-435-54150-1.

- Dobbin, L. (trans.) (1931). Collected Papers of Carl Wilhelm Scheele.

- Farber, Eduard ed. (1961). Great Chemists. New York: Interscience Publishers. pp. 255-261.

- Greenberg, Arthur. (2000). A Chemical History Tour: Picturing Chemistry from Alchemy to Modern Molecular Science. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 135-137.

- Greenberg, Arthur. (2003). The Art of Chemistry: Myths, Medicines and Materials. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 161-166.

- Schofield, Robert E (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773-1804. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Shectman (2003). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the 18th Century. Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

- Sootin, Harry (1960). 12 Pioneers of Science. New York: Vanguard Press.