John Smith of Jamestown

Captain Sir John Smith (c. January 1580–June 21 1631) Admiral of New England was an English soldier, sailor, and author. He is remembered for his role in establishing the first permanent English settlement in North America at Jamestown, Virginia, and his brief association with the Native American girl Pocahontas during an altercation with the Powhatan Confederacy and her father, Chief Powhatan. He was a leader of the Virginia Colony (based at Jamestown) between September 1608 and August 1609, and led an exploration along the rivers of Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay.

His books may have been as important as his deeds, as they encouraged more Englishmen and women to follow the trail he had blazed and colonize the New World. He gave the name New England to that region, and encouraged people with the comment, "Here every man may be master and owner of his owne labour and land...If he have nothing but his hands, he may...by industrie quickly grow rich." His message attracted millions of people in the next four centuries.

Contents |

Early adventures

John Smith was baptized on 9 January 1580 at Willoughby[1] near Alford, Lincolnshire where his parents rented a farm from Lord Willoughby. He was educated at King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth.[2] After his father died, Smith left home at age 16 and set off to sea. He served as a mercenary in the army of King Henry IV of France against the Spaniards, fought for Dutch independence from the Spanish King Phillip II, set off for the Mediterranean Sea, working on a merchant ship, and later fought against the Ottoman Empire in the Long War. Smith was promoted to captain while fighting for the Austrian Habsburgs in Hungary, in the campaign of Mihai Viteazul in 1600-1601. After the death of Mihai Viteazul, he fought for Radu Şerban in Wallachia against Ieremia Movilă, but in 1602 he was wounded, captured and sold as a slave.[3] Smith claimed the Turk (presumably hoping Smith would be a tutor in the short term, and a payer of a ransom in the long term) sent him as a gift to his sweetheart, who fell in love with Smith. He then was taken to Crimea, from where he escaped from the Ottoman lands into Muscovy then on to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Smith then traveled through Europe and Northern Africa, returning to England during 1604. Prior to his capture, Smith had defeated and killed three Turkish commanders in three duels, for which he was knighted by the Transylvanian Prince Sigismund Báthory and given a horse and coat of Arms showing three Turks heads. This all happened during the years 1601 to 1604.

Virginia Colony

In 1606, Smith became involved with plans to colonize Virginia for profit by the Virginia Company of London, which had been granted a charter from King James I of England. The expedition set sail in three small ships, the Discovery, the Susan Constant and the Godspeed, on December 20, 1606. His page was a 12-year-old boy named Samuel Collier.

John Smith was apparently a troublemaker on the voyage, and Captain Christopher Newport (in charge of the three ships) had planned to execute him upon arrival in Virginia. However, upon first landing at what is now Cape Henry on April 26, 1607, sealed orders from the Virginia Company were opened. They designated Smith to be one of the leaders of the new colony, forcing Newport to spare him. The search for a suitable site ended on May 14, 1607, when Captain Edward Maria Wingfield, president of the council, chose the Jamestown site as the location for the colony.

Harsh weather, lack of water and attacks from Algonquian tribes of the Native Americans almost destroyed the colony. In December 1607, while seeking food along the Chickahominy River, Smith was captured and taken to meet the Chief of the Powhatans, Potwahatan, at Werowocomoco, the chief village of the Powhatan Confederacy on the north shore of the York River about 15 miles due north of Jamestown, and 25 miles downstream from where the river forms from the Pamunkey River and the Mattaponi River at West Point, Virginia. Although he feared for his life, Smith was eventually released without harm and later attributed this in part to the chief's daughter, Pocahontas, who, according to Smith, threw herself across his body[4]: "at the minute of my execution, she hazarded [i.e. risked] the beating out of her own brains to save mine; and not only that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestown".[5]

Smith's version of events is the only source, and since the 1860s, scepticism has increasingly been expressed about its veracity. One reason for such doubt is that despite having published two earlier books about Virginia, Smith's earliest surviving account of his rescue by Pocahontas dates from 1616, nearly 10 years later, in a letter entreating Queen Anne to treat Pocahontas with dignity.[6] The time gap in publishing his story raises the possibility that Smith may have exaggerated or invented the event to enhance Pocahontas's image. However, in a recent book, Lemay points out that Smith's earlier writing was primarily geographical and ethnographic in nature and did not dwell on his personal experiences; hence there was no reason for him to write down the story until this point.[7]

Henry Brooks Adams, the pre-eminent Harvard historian of the second half of the 19th century, attempted to debunk Smith’s claims of heroism. He said that Smith’s recounting of the story of Pocahontas had been progressively embellished, made up of “falsehoods of an effrontery seldom equalled in modern times.” Although there is general consensus among historians that Smith tended to exaggerate, his account does seem to be consistent with the basic facts of his life. Adams' attack on Smith, an attempt to deface one of the icons of Southern history, was motivated by political considerations in the wake of the Civil War. Adams had been influenced to write his fusillade against Smith by John G. Palfrey who was promoting New England colonization, as opposed to southern settlement, as the founding of America. The accuracy of Smith’s accounts has continued to be a subject of debate over the centuries.[8].

Some experts have suggested that, although Smith believed he had been rescued, he had in fact been involved in a ritual intended to symbolize his death and rebirth as a member of the tribe.[9][10] However, in Love and Hate in Jamestown, David A. Price notes that this is only guesswork, since little is known of Powhatan rituals, and there is no evidence for any similar rituals among other North American tribes (p. 243-4).

Whatever really happened, the encounter initiated a friendly relationship with Smith and the colonists at Jamestown. As the colonists expanded further, however, some of the Native Americans felt that their lands were threatened, and conflicts arose again.

In 1608, Pocahontas is said to have saved Smith a second time. Smith and some other colonists were invited to Werowocomoco by Chief Powhatan on friendly terms, but Pocahontas came to the hut where the English were staying and warned them that Powhatan was planning to kill them. Due to this warning, the English stayed on their guard, and the attack never came.[11]

Later, Smith left Jamestown to explore the Chesapeake Bay region and search for badly-needed food, covering an estimated 3,000 miles.[12] In his absence, Smith left his friend Matthew Scrivener, a young gentleman adventurer from Sibton, Suffolk, who was related by marriage to the Wingfield family, as Governor in his place. When he returned, he discovered that Scrivener[13] wasn't cut out to be an administrator, and so Smith was eventually elected president of the local council in September 1608 and instituted a policy of discipline, encouraging farming with a famous admonishment: "He who does not work, will not eat."[14]

The settlement grew under his leadership. During this period, Smith took the chief of the neighbouring tribe hostage and, according to Smith he did, "take this murdering Opechancanough...by the long lock of his head; and with my pistol at his breast, I led him {out of his house} amongst his greatest forces, and before we parted made him [agree to] fill our bark with twenty tons of corn." A year later, full-scale war broke out between the Powhatans and the Virginia colonists. Smith was seriously injured by a gunpowder burn after a rogue spark landed in his powder keg. He returned to England for treatment in October 1609, and he never returned to Virginia. He was succeeded as governor by an aristocrat adventurer, George Percy.

- See also: Jamestown, Virginia

New England

In 1614, Smith returned to the Americas in a voyage to the coasts of Maine and Massachusetts Bay, and named the region "New England".[15] His second attempted voyage to the New England coast in 1615 was interrupted when he was captured by French pirates off the Azores. Smith escaped after weeks of captivity and made his way back to England, where he published an account of his two voyages as A Description of New England. He never left England again, and spent the rest of his life writing books. He died in 1631.

Publications

- A True Relation of Such Occurrences and Accidents of Note as Happened in Virginia (1608)

- A Map of Virginia (1612)

- The Proceedings of the English Colony in Virginia (1612)

- A Description of New England (1616)

- New England's Trials (1620, 1622)

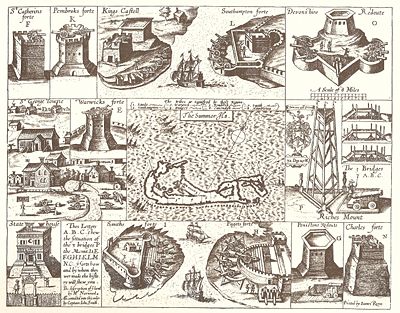

- The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624)

- An Accidence, or the Pathway to Experience Necessary for all Young Seamen (1626)

- A Sea Grammar (1627) - the first sailors' word book in English

- The True Travels, Adventures and Observations of Captain John Smith (1630)

- Advertisements for the Unexperienced Planters of New England, or Anywhere (1631)

John Smith Memorial, New Hampshire

The Captain John Smith Memorial currently lies in disrepair off the coast of New Hampshire on Star Island, part of the Isles of Shoals. Built in 1864 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of John Smith's visit, the original monument was a tall pillar set on a triangular base atop a series of steps surrounded by granite supports and a sturdy iron railing. At the top of the original obelisk were three carved faces, representing the severed heads of three Turks that Smith lopped off while in combat during his stint as a soldier in Transylvania.[16]

In 1914, the New Hampshire Society of Colonial Wars partially restored and rededicated the monument for the 300th anniversary celebration of his historic visit.[17] The monument had weathered so badly in the harsh coastal winters that the inscription in the granite had worn away.

John Smith in film

- John Smith is one of the main characters in Disney's 1995 film Pocahontas and its straight-to-video sequel Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World. He is voiced by Mel Gibson in the first movie and his younger brother Donal Gibson in the sequel.

- Smith and Pocahontas are also central characters in the Terrence Malick film The New World, in which he was portrayed by Colin Farrell.

- Captain Smith was portrayed by Anthony Dexter in the 1953 low-budget film Captain John Smith and Pocahontas.

Notes

- ↑ Lefroy, John Henry (1882), The Historye of the Bermudaes Or Summer Islands, Hakluyt Society, p. iv, http://books.google.com/books?id=of86AAAAIAAJ&dq=%22John+Smith%22+was+baptized+%22January+1580%22&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0, retrieved on 2008-09-21

- ↑ "History of the School". King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth. Retrieved on 2008-06-21.

- ↑ Soldier of Furtune: John Smith before Jamestown

- ↑ Smith, Generall Historie

- ↑ Smith. Letter to Queen Anne.

- ↑ Smith. Letter to Queen Anne.

- ↑ Lemay. Did Pocahontas, p. 25. Lemay's other arguments in favour of Smith are summarized in Birchfield, 'Did Pocahontas'.

- ↑ Lepore, Jill, "The New Yorker", Ap. 2, 2007, p. 40-45

- ↑ Gleach, Powhatan's World, pp. 118-21.; Kupperman, Indians and English, pp. 114, 174.

- ↑ Horwitz, Tony. A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World. Henry Holt and Co.. pp. 336. ISBN 0-8050-7603-4.

- ↑ Symonds, Proceedings, pp. 251-2; Smith, Generall Historie, pp. 198-9, 259.

- ↑ These explorations have been commemorated in the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail, established in 2006.

- ↑ Scrivener would later drown along with Bartholomew Gosnold's brother in an ill-fated voyage to Hog Island during a storm.

- ↑ To Conquer is To Live: The Life of Captain John Smith of Jamestown, Kieran Doherty, Twenty-first Century Books, 2001

- ↑ New England. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 20, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service: [1]

- ↑ J. Dennis Robinson The Ugliest Monument in New England

- ↑ Robinson. John Smith Memorial Photo History

Further reading

- Horn, James, ed. Captain John Smith, Writings, with Other Narratives of Roanoke, Jamestown, and the English Settlement of America (Library of America, 2007) ISBN 978-1-59853-001-8.

- Philip L. Barbour, The Jamestown Voyages under the First Charter, 1606-1609, 2 vols., Publications of the Hakluyt Society, ser.2, 136-37 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969)

- A. Bryant Nichols Jr., Captain Christopher Newport: Admiral of Virginia, Sea Venture, 2007

- Philip L. Barbour, The Three Worlds of Captain John Smith (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1964)

- Gleach, Frederic W. Powhatan's World and Colonial Virginia. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

- Dorothy Hoobler and Thomas Hoobler, Captain John Smith: Jamestown and the Birth of the American Dream (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2006)

- Horn, James. A Land as God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America (New York: Basic Books, 2005)

- Kupperman, Karen Ordahl ed., John Smith: A Select Edition of His Writings (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988)

- Price, David A., Love and Hate in Jamestown: John Smith, Pocahontas, and the Heart of a New Nation (New York: Knopf, 2003)

- Lemay, J.A. Leo. Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith? Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1992, p. 25.

- Giles Milton, Big Chief Elizabeth: The Adventures and Fate of the First English Colonists in America, Macmillan, New York, 2001

- John Smith, The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1580-1631) in Three Volumes, edited by Philip L. Barbour, 3 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for The Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, 1986)

- Smith, John. The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles. 1624. Repr. in Jamestown Narratives, ed. Edward Wright Haile. Champlain, VA: Roundhouse, 1998. pp. 198-9, 259.

- Smith, John. Letter to Queen Anne. 1616. Repr. as 'John Smith's Letter to Queen Anne regarding Pocahontas'. Caleb Johnson's Mayflower Web Pages. 1997. Accessed 23 April, 2006.

- Symonds, William. The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia. 1612. Repr. in The Complete Works of Captain John Smith. Ed. Philip L. Barbour. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986. Vol. 1, pp. 251-2

- Warner, Charles Dudley, Captain John Smith, 1881. Repr. in Captain John Smith Project Gutenberg Text, accessed 4 July, 2006

External links

- Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail Official Website

- Friends of the John Smith Trail

- NGS Then and Now - John Smith

- Captain John Smith Trail in Virginia

- John Smith Water Trail Blog

- The Captain John Smith Water Trail

- A Description of New England (1616) online text (PDF)

- Our Most Politically Incorrect Founding Father (WorldNet Daily)

- The Ugliest Monument in New England (seacoastnh.com)

- The Ugliest Monument in New England II

- John Smith Memorial Photo History

- Captain John Smith Chesapeake NHT is administered by the Chesapeake Bay Gateways and Watertrails Network

- John Smith 400 Project - 2007 Re-enactment Voyage

- Smith Water Trail Loops

- Complete text of the Generall Historie American Memory

- Texts of Imagination & Empire, by Emily Rose, Princeton University Folger Shakespeare Library

| Preceded by Matthew Scrivener |

Colonial Governor of Virginia 1608-1609 |

Succeeded by George Percy |

|

|||||||