Canute the Great

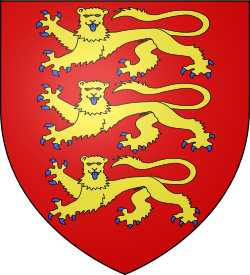

| Canute the Great | |

|---|---|

| King of England, Denmark, Norway and the Swedes | |

| Reign | England: 1016 - 1035 Denmark: 1018 - 1035 Norway: 1028 - 1035 |

| Predecessor | Edmund Ironside (England) Harald II (Denmark) Olaf Haraldsson (Norway) |

| Successor | Harold Harefoot (England) Harthacanute (Denmark) Magnus Olafsson (Norway) |

| Spouse | Aelgifu of Northampton Emma of Normandy |

| Issue | Sweyn Knutsson Harold Harefoot Harthacanute Gunhilda of Denmark |

| Father | Sweyn Forkbeard |

| Mother | Saum-Aesa, also known as Gunnhilda |

| Born | c.985 - c.995 Denmark |

| Died | 12 November 1035 England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) |

| Burial | Old Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral |

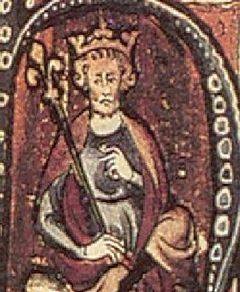

Canute the Great, also known as Cnut in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, or Knut (Old Norse: Knútr inn ríki, Norwegian: Knut den mektige, Swedish: Knut den Store, Danish: Knud den Store, Polish: Kanut Wielki) (died 12 November 1035) was a Viking king of England and Denmark, and Norway, and of some of Sweden[1] (such as the Sigtuna[2] Swedes). His successes as a statesman, politically and militarily, and the high status he enjoyed among medieval Europe's magnates, winning a number of concessions for his people in diplomacy with the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, often cause modern historians to call him Emperor of the North,[3] although this is an unofficial title.

In a letter written on a journey to Rome, after his victory over the kings of Norway and Sweden, Canute proclaims himself king of all England and Denmark and the Norwegians and of some of the Swedes.[4] His kingship of England, and the concomitant struggles of the kings of Denmark for preeminence within Scandinavia, though, meant Canute held a considerable overlordship across other areas of the British Isles too, in line with his Anglo-Saxon predecessors,[5] and the leader of the strongest Viking regime in history. Uncertain though the extent of this dominance is, we can say Canute's rule was felt by the sea-kingdoms of the Viking settlers among the Celtic nations, known as the Gall Gaidel. These were the Kingdom of the Isles (probably under direct overlordship through Håkon Eiriksson),[6] in the Sea of the Hebrides, and the Kingdom of Dublin (probably on the terms of vassal and suzerain),[7] in the Irish Sea. His main aim here was for control of the western seaways to and from Scandinavia, and to check the might of the Earls of Orkney.[8] At the height of his reign, certain Gaelic kingdoms,[9] and the dominant Ui Imhair sea-kingdom,[10] were in clientage with Canute too.

Birth and kingship

Canute was a son of the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard, and an heir to a line of Scandinavian rulers central to the unification of Denmark,[11] with its origins in the shadowy figure of Harthacnut, founder of the royal house, and the father to Gorm the Old, its official progenitor. His mother's name is unknown, although the Slavic princess, Saum-Aesa, daughter to Mieszko I of Poland (in accord with the Monk of St Omer's, Encomium Emmae[12] and Thietmar of Merseburg's contemporary Chronicon[13]), is a possibility.[14] Some hint at his childhood can be found in the Flateyjarbók, a 13th century source, with a statement Canute was taught his soldiery by the chieftain Thorkell the Tall,[15] brother to Sigurd, Jarl of mythical Jomsborg, and the legendary Joms, at their Viking stronghold; now thought to be a Slav (as well as Scandinavian) fortress on the Island of Wollin, off the coast of Pomerania.

Canute's date of birth, like his mother's name, is unknown. Contemporary works such as the Chronicon and the Encomium Emmae, do not mention it. Still, in a Knutsdrapa by the skald Ottar the Black there is a statement that Canute was 'of no great age' when he first went to war.[16] It also mentions a battle identifiable with Forkbeard's invasion of England, and attack on the city of Norwich, in 1003/04, after the St. Brice's Day massacre of Danes by the English, in 1002. If it is the case that Canute was part of this, his birthdate may be near 990, or even 980. If not, and the skald's poetic verse envisages another assault, with Forkbeard's conquest of England in 1013/14, it may even suggest a birth date nearer 1000.[17] There is a passage of the Encomiast's (as the author of the Encomium Emmae is known) with a reference to the force Canute lead in his English conquest of 1015/16. Here (see below) it says all the Vikings were of 'complete manhood' under Canute 'the king'.

A description of Canute can be found within the 13th century Knýtlinga saga:

Knutr was exceptionally tall and strong, and the handsomest of men, all except for his nose, that was thin, high-set, and rather hooked. He had a fair complexion none-the-less, and a fine, thick head of hair. His eyes were better than those of other men, both the handsomer and the keener of their sight.

Hardly anything is known for sure of Canute's life until the year he was part of a Scandinavian force under his father, the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard; with his invasion of England in summer 1013. It was the climax to a succession of Viking raids spread over a number of decades. The kingdom fell quickly. In the months after, Forkbeard was in the process of consolidating his kingship, with Canute left in charge of the fleet, and the base of the army at Gainsborough, the capital of Forkbeard's regime. At a turn of fortune, though, with Sweyn's sudden death, in February 1014, Canute was held to be king[20]. This was not to be a simple succession though, for the Viking forces, since the use of mercenaries was common in Scandinavia, were probably short of some of their combatants, likely sent home for winter once their payments had been made. And the English nobility were loath to accept Canute's sovereignty over the kingdom.

At the Witan, an Anglo-Saxon high-council, there was a vote for the former king,[21] Ethelred the Unready, an Anglo-Saxon of the Wessex royal house, to return from exile with his in-laws in Normandy. It was a move which meant Canute had to abandon England and set sail for Denmark, while the nobility of England, possibly with Normans in their forces, made the kingdom theirs once again. On the beaches of Sandwich the Vikings put to shore to mutilate their hostages, taken from the English as pledges of allegiance given to Canute's father.[22]

On the death of Sweyn Forkbeard his eldest son, Harald, was to be King of Denmark. Canute, supposedly, made the suggestion they might have a joint kingship, although this found no ground with his brother.[23] Harald is thought to have made an offer to Canute to command the Vikings for another invasion of England, on the condition he did not continue to press his claim.[24] Canute, if we accept this is true, did not, and had his men make the ships ready for another invasion. This one was to be final, and the forces were even greater.[25]

Conquest of England

In the summer of 1015, Canute's fleet set sail for England with a Danish army of maybe 10,000, in 200 longships.[26] Among the allies of Denmark was Boleslaw the Brave. He was the Duke of Poland, and a relative to the Danish royals. He lent some token Slav troops,[27] likely to have been a pledge made to Canute and Harald when, in the winter, they "went amongst the Wends" to fetch their mother back to the Danish court after she was sent away by their father, who its seems wed another woman, to seal an alliance with the Swedish king.[28] Olof Skötkonung, son of Sigrid the Haughty by her first husband, the Swedish king Eric the Victorious, and an in-law to the royals of Denmark by Sigrid's second husband, Sweyn Forkbeard, was an ally. Eiríkr Hákonarson, was an in-law to Canute and Harald too, and Trondejarl, the Earl of Lade, and the co-ruler of Norway, with his brother Svein Hakonarson, under Danish sovereignty - Norway was won by the Danes, with the Swedes in alliance, as well as Norwegians, at the Battle of Svolder, in 999. Erik's son Hakon, was left to rule Norway with Svein when he went to support Canute, although at the Battle of Nesjar, in 1016, Olaf Haraldsson won the Kingdom for himself, Hakon went to support Canute's conquest of England, and Sveinn to Sweden, in hopes to return to Norway, yet he died shortly after.

Thorkell the Tall, a Jomsviking chief who had fought against the Viking invasion of Canute's father, with a pledge of allegiance to the English in 1012,[29] was among Canute's retinue. Some explanation for this shift of allegiance may be found in a stanza of the Jómsvíkinga saga which mentions two attacks against Jomsborg's mercenaries while they were in England, with a man known as Henninge among their casualties, a brother of Thorkell's.[30] If this man was Canute's childhood mentor, it explains his acceptance of this ally. It seems Canute and the Jomsviking, ultimately in the service of Jomsborg, were in a very difficult relationship with each other.

Canute was at the head of an array of Vikings, from all over Scandinavia. Altogether, the invasion force was to be in often close and grisly warfare with the English for the next fourteen months. Practically all of the battles were fought against Ethelred the Unready's son, and the staunchest opponent of Canute, Edmund Ironside.

According to the Peterborough version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, early in September 1015 Canute 'came into Sandwich, and straightway sailed round Kent to Wessex, until he came to the mouth of the Frome, and harried in Dorset and Wiltshire and Somerset'.[31] A passage from Emma's Encomium describes a scene when Canute made landfall in England:

[T]here were so many kinds of shields, that you could have believed that troops of all nations were present. … Gold shone on the prows, silver also flashed on the variously shaped ships. … For who could look upon the lions of the foe, terrible with the brightness of gold, who upon the men of metal, menacing with golden face, … who upon the bulls on the ships threatening death, their horns shining with gold, without feeling any fear for the king of such a force? Furthermore, in this great expedition there was present no slave, no man freed from slavery, no low-born man, no man weakened by age; for all were noble, all strong with the might of mature age, all sufficiently fit for any type of fighting, all of such great fleetness, that they scorned the speed of horsemen.

—Encomium Emmae Reginae[32]

Upon their disembarkment the Vikings had soon made the weight of their arm felt in Wessex,[33] and stood their ground until mid-winter, with the English king in London. At this point[34] Eadric Streona, a nobleman risen far under his king Ethelred the Unready to be the wealthy Earl of Mercia, perhaps even the richest of the English nobility, thought it prudent to join in with Canute and the Vikings, along with forty ships, although these were probably of the Danelaw anyway.[35] England's king was under pressure, and the distresses which were a fact of his reign, given his ascension to England's throne by the ruse of assassination, were apparently too much for many of his vassals to take.

Canute went across the Thames, at mid-winter, with no pause in bleak weather, northwards, to confront Uhtred, the Earl of Northumbria. Like Wessex, the heartland of the Anglo-Saxon regime, Northumbria fell quickly. Its lands without their main garrisons, as Uhtred was away in Mercia with Edmund Ironside, now ruler of the Five Borough's[36], to countermand the lands of Eadric. Uhtred, with his own lands now in the hands of his enemies, thought it wise to sue for peace. He was nevertheless executed for breaking oaths of allegiance to Sweyn Forkbeard. Eiríkr Hákonarson, most likely with another force of Scandinavians, came to support Canute at this point.[37]He strategically left the Norwegian in control of Northumbria before his southward advance.

Ironside was effectively swept towards London, his last stronghold, and the death of Ethelred II within its walls, on 23 April, meant he was chosen as king by the populace. Canute brought his ship to London in May, and over the next few months the Vikings made their camps on the fringes of the city. He saw to the construction of dikes on the northern and southern flanks; a channel was even dug across the southern banks of the Thames for the longships to cut London off up-river. England's king, though, broke out of London before Canute's encirclement was complete,[38] to gather his men, in Wessex, and the Vikings broke off a portion of their siege in pursuit. The English were able to rally at Penselwood, in Somerset; with a hill in Selwood Forest as the likely location of their stand. The battle that was fought there did not leave any clear victor. A subsequent battle at Sherston, in Wiltshire, was fought over two days and again left neither side victorious.

Edmund did actually manage to break the siege of London. With the losses on the English side too heavy though, Canute brought his forces back together, and the besiegers again lay their attentions on the steadfast walls.[39] London was still held by the English though, and the escape of their king from the siege meant Canute's strategy was under threat. He apparently had to make it a priority to search for supplies, nominally amongst his allies in Mercia. At this point Eadric thought it wise to ally himself with Edmund again, now the Vikings were set to pillage his lands. Canute's men were subsequently put under attack in Mercia, with Eadric's, as well as Edmund's men now against them. At the Battle of Brentford, Edmund fought the besiegers off their dikes on the outskirts of London, and back to their ships, on the Isle of Sheppey, in Kent. Englishmen wanton for loot went too far ahead of the main army in pursuit of the Vikings, and many lost their lives.[40] The invasion force went across the estuary of the river Thames with its disembarkment in Essex.

In October the two armies came together for a final confrontation at the Battle of Assandun, the site of which may have been either Ashingdon or Ashdon, both in Essex. Canute won this decisively. Eadric Streona betrayed his countrymen, with he and his men retreating in the heat of battle. His army beaten, Edmund, likely to have been a casualty himself, made his escape; to be caught near the Forest of Dean, in Gloucestershire, where there was likely to have been a final struggle made in an attempt by the English to protect their king. Canute was ultimately able to manoeuvre negotiations, with a rendezvous on an island in the Severn.

Accepting defeat, the English king came to an agreement with Canute on the island of Alney, near Gloucester, in which all of England north of the Thames was to be the domain of the Danish prince.[41] Its key clause was that by the death of one of the two, the other should be the one and only King of England, his sons being the heirs. It was a move of astute political sense on the part of Canute. After Edmund Ironside's death on 30 November, possibly at the hands of the traitor Eadric Streona's men, yet probably as a result of his wounds after Assandun, Canute was his successor. His coronation was at Christmas, with recognition by the nobility in January the next year.

Canute, a Viking, was to be one of England's most successful kings. His statesmanship, with a sure protection against raiders, brought in a prosperous era of stability. The reign of this wealthy nation, and the pedigree of his Danish heritage, meant he was eventually able to manoeuvre an overlordship within Scandinavia, and substantial parts of the British Isles too.[42]

King of England

In July 1017, Canute married Emma of Normandy, the widow of Ethelred, and daughter of Richard the Fearless, the first Duke of Normandy. With this marriage he was able to elevate his line above the heirs of England's overthrown dynasty, in the eyes of the Normans, as well as protect himself against his enemies, with Emma and Ethelred's sons Edward the Confessor and Alfred Atheling in exile amongst their relatives. His wife held the keys to a secure English court in several ways. Canute put forward their son Harthacanute to be his heir; his two sons from his marriage to Aelgifu of Northampton, his handfast wife, were left on the sidelines. He sent Harthacanut to Denmark when he was still a boy, and the heir to the throne was brought up, as Canute was himself, a Viking.

England's division amongst the four great Earldoms was a decree of Canute's kingship. These were Wessex, his personal fief, Mercia, for Eadric, East Anglia, for Thorkel, and Northumbria, for Erik. This was the basis for the system of feudal baronies, which underlay sovereignty of English rulers for centuries, while the formation of the Norman counties - stronger, yet synonymous versions of the Anglo-Saxon shires - came to countermand the might of the great Earls. Even under Canute these men were a real threat. Edmund Ironside's, as well as Canute's betrayer, Eadric Streona, was not Earl of Mercia for long. His execution, in 1017, was only a year after Canute's coronation, at Christmas, in London.[43] Mercia went to a noble family of the Hwicce, probably to Leofwine, a survivor from Ethelred's reign, and by the 1030s, to his son Leofric,[44] whose wife was one Lady Godiva, a figure of English folklore.

The very last Danegeld ever paid, a sum of 82,500 pounds, went to Canute in 1018. After their staunch resistance, as well as the fact of their mercantile wealth, 10,500 pounds was levied from the citizenry of London alone. Canute felt secure enough to allow his Vikings to return to their lands in Scandinavia with 72,000 pounds in payment for services the same year. He, with his huscarls, and the no doubt grateful earls, were left to control England.

Canute's brother Harald was possibly at Canute's coronation, in 1016, maybe even for the conquest, with his return to Denmark, as its king, with part of the fleet, at some point thereafter.It is only certain, though, there was an entry of his name, alongside Canute's, in a confraternity with Christ Church, Canterbury,[45] in 1018. This, though, is not conclusive, for the entry may have been made in Harald's absence, by the hand of Canute himself even, which means, while it is usually thought that Harald died in 1018, it is unsure if he was even alive to do this. Entry of his brother's name in the Canterbury codex may have been Canute's attempt to make his vengeance for Harald's murder good with the Church. Of course, this was maybe just a gesture for a soul to be under God's protection. There is evidence Canute was in battle with pirates in 1018, with his destruction of the crews of thirty ships,[46] although it is unknown if this was off the English or Danish shores. He himself mentions troubles in his 1019 letter (to England, from Denmark), written as the King of England and Denmark. These events can be seen, with plausibility, to be in connection with the death of Harald. Canute says he dealt with dissenters to ensure Denmark was free to assist England.[47] His words tell us some of what it is that the situation was:

King Cnut greets in friendship his archbishop and his diocesan bishops and Earl Thurkil and all his earls... ecclesiatic and lay, in England... I inform you that I will be a gracious lord and a faithfull observer of God's rights and just secular law. (He exhorts his ealdormen to assist the bishops in the maintenance of) God's rights... and the benefit of the people.

If anyone, ecclesiastic or layman, Dane or Englishman, is so presumptuous as to defy God's law and my royal authority or the secular laws, and he will not make amends and desist according to the direction of my bishops, I then pray, and also command, Earl Thurkil, if he can, to cause the evil-doer to do right. And if he cannot, then it is my will that with the power of us both he shall destroy him in the land or drive him out of the land, whether he be of high or low rank. And it is my will that all the nation, ecclesiatical and lay, shall steadfastly observe Edgar's laws, which all men have chosen and sworn at Oxford.

Since I did not spare my money, as long as hostility was threatening you, I with God's help have put an end to it. Then I was informed that greater danger was approaching us than we liked at all; and then I went myself with the men who accompanied me to Denmark, from where the greatest injury had come to us, and with God's help I have made it so that never henceforth shall hostility reach you from there as long as you support me rightly and my life lasts. Now I thank Almighty God for his help and his mercy, that I have settled the great dangers which were approaching us that we need fear no danger to us from there; but we may rekon on full help and deliverance, if we need it

—Cnut's letter of 1019[48]

The wars he fought to secure his kingship were an opportunity for some of his English subjects to prove their worth. Godwin was one notable figure; by the lengths he went to for his king in battle with his enemies, Canute thought it good to award him the earldom of Wessex, and the role of he and his family was prominent in English affairs until the Norman Conquest. One of his sons was Harold Godwinson.

Through his reign, Canute brought together the English and Danish kingdoms, and the people saw a golden age of dominance across Scandinavia, as well as within the British Isles.[49] His mutilation of the hostages at Sandwich is ultimately seen to be uncharacteristic of his rule. He reinstated the Laws of King Edgar to allow for the constitution of a Danelaw, and the activity of Scandinavians at large. He also reinstituted the extant laws with a series of proclamations to assuage common grievances brought to his attention. Two significant ones were: On Inheritance in case of Intestacy, and, On Heriots and Reliefs. He strengthened the currency, initiating a series of coins of equal weight to those being used in Denmark and other parts of Scandinavia. This meant the markets grew, and the economy of England was able to spread itself, as well as widen the scope of goods to be bought and sold.

Canute was generally thought to be a wise and successful king of England, although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the Church, keeper of the historic record. Either way, he brought decades of peace and prosperity to England. His numerous campaigns abroad meant the tables of Viking supremacy were stacked in favour of the English, turning the prows of the longships towards Scandinavia. The medieval Church was adept to success, and put itself at the back of any strong and efficient sovereign, if the circumstances were right for it. Thus we hear of him, even today, as a religious man, despite the fact that he was in an effectively sinful relationship, with two wives, and the harsh treatment of his fellow Christian opponents. Canute was ruler across a domain beyond any monarchs of England, until the adventures of the imperial European colonies, and the empire of the English.

King of Denmark

Upon Sweyn Forkbeard's death, Canute's brother Harald was King of Denmark. It is thought Canute went to Harald to ask for his assistance in the conquest of England, and the division of the Danish kingdom. His plea for division of kingship was denied, though, and the Danish kingdom remained wholly in the hands of his brother, although, Harald lent to Canute the command of the Danes in any attempt he was of a mind to lead on the English throne. Harald probably saw it was out of his hands anyway. It was a vendetta that held his brother, Canute, and the Vikings driven away in spite of their conquest with Forkbeard. They were bound to fight again, on the basis of vengeance for their slight.

It is possible Harald was at the siege of London, and the King of Denmark was content with Canute in control of the army. His name was to enter the fraternity of Christ Church, Canterbury, at some point, in 1018, although it is unsure if it was before or after he was back in Denmark.

In 1018, Harald died and Canute went to Denmark to affirm his succession to the Danish crown. With a letter written in 1019 he states his intentions to avert troubles to be done against England. It seems Danes were set against him, while an attack on the Wends of Pomerania, in which Godwin apparently earned the king's trust with a raid he led himself at night, was possibly in relation with this. In 1020 he was back in England, his hold on the Danish throne presumably stable. Ulf Jarl, his brother-in-law, was his appointee as the Earl of Denmark. Canute's son, Harthacanute was left in his care.

When the Swedish king Anund Jakob and the Norwegian king Olaf Haraldsson took advantage of Canute's absence and began to launch attacks against Denmark, Ulf gave the discontent freemen cause to take Harthacanute, still a child, as king. This was a ruse of Ulf's, since the role he had as the caretaker of Harthacanute subsequently made him the ruler of the kingdom.

When news of these events came to Canute, in 1026, he brought together his forces, and, with Ulf in line again, won Denmark supremacy in Scandinavia, at the Battle of Helgeå. This service, did not, though, earn the usurper the forgiveness of Canute for his coup. At a banquet in Roskilde, the brothers-in-law were sat at a game of chess and an argument arose between them, and the next day, Christmas of 1026, one of Canute's housecarls, with his blessing, killed Ulf Jarl, in the Church of Trinity. Contradictory evidences of Ulf's death gather doubt to these circumstances though. Evidence for the years of Canutes reign in Denmark, with his mainstay in England, is generally scanty.

King of Norway and part of Sweden

Earl Eiríkr Hákonarson was ruler of Norway under Canute's father, Forkbeard, and Norwegians under Erik had assisted in the invasion of England in 1015-16. Canute showed his appreciation, awarding Eiríkr the office to the Earldom of Northumbria. Sveinn, Eiríkr's brother, was left in control of Norway, but he was beaten at the Battle of Nesjar, in 1015 or 1016, and Eiríkr's son, Håkon, fled to his father. Olaf Haraldsson, of the line of Fairhair, then became King of Norway, and the Danes lost their control.

Thorkell the Tall, said to be a chieftain of the Jomsvikings, was a former associate of the new Norwegian king, and the difficulties Canute found in Denmark, as well as with Thorkell, may perhaps be best seen in relation to Norwegian pressure on the Danish lands. By the time of Olof Skötkonung's death in 1022, and the succession to the Swedish throne of his son, Anund Jacob, another opponent of Canute, there was cause for a demonstration of Danish strength in the Baltic. Jomsborg, the legendary stronghold of the Jomsvikings, thought to be on an island off the coast of Pomerania, was probably the target of Canute's expedition.[50] After his banishment from England in 1021, and the clear display of the intentions of the king of England and Denmark to dominate Scandinavian affairs, it seems Thorkell was wont to reconcile himself with Canute in 1023. The alliance between the kings of Norway and Sweden, against Canute, though, meant there was soon to be war.

In a battle known as the Holy River, Canute and his men fought the Swedes and Norwegians led by the kings Olaf Haraldsson and Anund Olafsson at the mouth of the river Helgea. 1026 is the likely date, and the apparent victory left Canute in control of Scandinavia, confident enough with his dominance to accept an invitation to Rome for the coronation of Conrad II as Holy Roman Emperor on 26 March 1027. In his Letter, written on the journey, he considers himself “King of all England and Denmark, and the Norwegians, and some of the Swedes”[51] (victory over Swedes suggests Helgea to be a river near Sigtuna, while Sweden's king appears to have been made a renegade, with a hold on the parts of Sweden which were too remote to threaten Canute, or even for Canute to threaten him). He also stated his intention to return to Denmark, for the secureing of a peace between the kingdoms of Scandinavia.

In 1028, after his return from Rome, through Denmark, Canute set off from England with a fleet of fifty ships,[52] to Norway, and the city of Trondheim. Olaf Haraldsson stood down, unable to put up any fight, as his nobles were against him, with offers of gold from Canute, and the apparent resentment for their king's tendency to flay their wives for sorcery.[53] Canute was crowned king, his was now King of England and Denmark, and Norway (he was not King of Sweden, only some of the Swedes)[54]. He entrusted the Earldom of Lade to the former line of earls, in Håkon Eiriksson, with Earl Eiríkr Hákonarson probably dead at this date.[55] Hakon was possibly the Earl of Northumbria after Erik too.[56]

Hakon, a member of a family with a long tradition of hostility towards the independent Norwegian kings, and a relative of Canute's, was already in lordship over the Isles, with the earldom of Worcester, possibly from 1016-17. The sea-lanes through the Irish Sea and Hebrides, led to Orkney and Norway, and were central to Canute's ambitions for dominance of Scandinavia, as well as the British Isles. Hakon was meant to be Canute's lieutenant of this strategic chain. And the final component was his installation as the king's deputy in Norway, after the expulsion of Olaf Haraldsson in 1028. Hakon, though, died in a shipwreck in the Pentland Firth, between the Orkneys and the Scottish mainland, either late 1029 or early 1030.[57]

Upon the death of Hakon, Olaf Haraldsson was to return to Norway, with Swedes in his army. He, though, was to meet his death at the hands of his own people, at the Battle of Stiklestad, in 1030. Canute's subsequent attempt to rule Norway without the key support of the Trondejarls, through Aelgifu of Northampton, and his eldest son by her, Sweyn Knutsson, was not a success. It is known as Aelfgifu's Time in Norway, with heavy taxation, a rebellion, and the restoration of the former Norwegian dynasty under Saint Olaf's illegitimate son Magnus the Good.

Journey to Rome

On the death in 1024 of the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II, the Ottonian dynasty was at an end, and with Conrad II the Salian dynasty was begun. Canute left his affairs in the north, and went to the coronation of the King of the Romans, at Easter 1027, in Rome.

On the return journey his letter of 1027, like his letter of 1019, was written to inform his subjects in England of his intentions.[58] It is in this letter he proclaims himself ‘king of all England and Denmark and the Norwegians and of some of the Swedes’.[59] We must assume his enemies in Scandinavia were now at his leisure, if he was able to say this, as well as do the pilgrimage of considerable prestiege for rulers of Europe in the Middle-Ages to the heart of Christendom.

In his letter Canute says he went to Rome to repent for his sins, pray for redemption, and the security of his subjects, as well as negotiate with the Pope for a reduction in the costs of the pallium for English archbishops,[60] and for a resolution to the competition of the archdioceses of Canterbury, and Hamburg-Bremen, for superiority over the Danish dioceses. He also sought to improve the conditions for pilgrims, as well as merchants, on the road to Rome. In his own words:

... I spoke with the Emperor himself and the Lord Pope and the princes there about the needs of all people of my entire realm, both English and Danes, that a juster law and securer peace might be granted to them on the road to Rome and that they should not be straitened by so many barriers along the road, and harassed by unjust tolls; and the Emperor agreed and likewise King Robert who governs most of these same toll gates. And all the merchants confirmed by edict that my people, both merchants, and the others who travel to make their devotions, might go to Rome and return without being afflicted by barriers and toll collectors, in firm peace and secure in a just law.

—Cnut's letter of 1027[61]

'Robert' in Canute's text is probably a clerical error for Rudolph, the last ruler of an independent Kingdom of Burgundy. Hence, the solemn word of the Pope, the Emperor, and Rudolph, was by the witness of four archbishops, twenty bishops, and 'innumerable multitutes of dukes and nobles'.[62] This suggests it was before the ceremonies were at an end.[63] It is without doubt he threw himself into his role with zest.[64] His image as the just Christian king, statesman and diplomat, and crusader against unjustness, seems to be one with its roots in reality, as well as one he sought to project.

A good illustration of his status within Europe is the fact Canute, and the King of Burgundy went alongside the emperor in the imperial procession,[65] and stood shoulder to shoulder with him on the same pedestal.[66] Canute and the successor of Charlemagne, in accord with various sources,[67] took one another's company like brothers, for they were of a similar age. Conrad gave his guest the sovereignty to lands in the Mark of Schleswig - the land-bridge between the Scandinavian kingdoms and the continent - as a token of their treaty of friendship.[68] Conflict in this area over past centuries was the cause for the construction of the Danevirke, from Schleswig, on the Schlei, and the Baltic Sea coast, to the marches of west Jutland, on the North Sea coast.

His visit to Rome was a triumph. In the verse of Sighvat's Knutsdrapa he praises Canute, his king, to be 'dear to the Emperor, close to Peter'.[69] In the days of Christendom, a king seen to be in favour with God could expect to be ruler over a happy kingdom.[70] He was surely in a stronger position, not only with the Church, and the people, but with the alliance of his southern rivals he was able to conclude his conflicts with his rivals in the north. His letter not only tells his countrymen of his achievements in Rome, but also of his ambitions within the Scandinavian world at his arrival home:

... I, as I wish to be made known to you, returning by the same route that I took out, am going to Denmark to arrange peace and a firm treaty, in the counsel of all the Danes, with those races and people who would have deprived us of life and rule if they could, but they could not, God destroying their strength. May he preserve us by his bounteous compassion in rule and honour and henceforth scatter and bring to nothing the power and might of all our enemies! And finally, when peace has been arranged with our surrounding peoples and all our kingdom here in the east has been properly ordered and pacified, so that we have no war to fear on any side or the hostility of individuals, I intend to come to England as early this summer as I can to attend to the equipping of a fleet.

—Cnut's letter of 1027[71]

Canute was to return to Denmark from Rome, by the road he had set out, make arrangements for some kind of pact with the peoples of Scandinavia - though it is not known precisely what it is that this was, his 1019 letter says he went to Denmark to secure support for his English kingdom, and this was probably the purpose of the endeavours he alludes to through his 1027 letter - and return to England. We can only be sure there were important events on the horizon, and the fleet was probably the one he went to Norway with.

Overlordship outside his kingdoms

A verse from court poet, Sigvat Thordarson, recounts that famous princes brought their heads to Canute and bought peace. This verse mentions Olaf Haraldsson in the past tense, with his death at the Battle of Stiklestad, in 1030. It was therefore at some point after this, and the consolidation of Norway, Canute went to Scotland, with an army,[72] and the navy in the Irish Sea,[73] in 1031, to receive, without bloodshed, the submission of three Scottish kings; Maelcolm, Maelbeth, and Iehmarc[74]. One of these kings, Iehmarc, is Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, an Ui Imhair chieftain, and the ruler of a sea-kingdom thought to extend throughout the Irish Sea,[75] with Galloway and the Isle of Man among his domains. In 1036 he was to be king of Dublin.[76]

There is reason to believe Vikings of Ireland were in relations with Canute already, as they were with Sweyn Forkbeard.[77] A Lausavísa attributable to the skald Ottar the Black, suggests these relations were on the level of overlordship, when he greets the ruler of the Danes, Irish, English and Island-dwellers.[78] It is a possibility, though, his use of Irish here was meant to mean the Gall Ghaedil kingdoms, rather than the Gaelic kingdoms too. After Brian Boru's victories over Sigtrygg Silkbeard, and the Battle of Clontarf, in 1014, the Vikings were wont to opt for a commercial life in Ireland, rather than one of conquest.[79] Still, when the misinformation prone Encomiast names among Canute's domains, not only England, Denmark and Norway, but also Scotia and Britannia,[80] there may be just enough evidence to suggest there is no exaggeration, here, of his lordship over the British Isles.[81]

Relations with the Church

Canute's actions as a Viking conqueror had made him uneasy with the Church, and the secular people of England. He was already a Christian before he was king, although the Christianization of Scandinavia was not at all complete in his day. His ruthless treatment of the overthrown dynasty, as well as his open relationship with a concubine – Aelgifu of Northampton, his handfast wife, whom he kept as his northern queen when he wed Emma of Normandy, kept in the south, with an estate in Exeter – did not fit with the emergent ideals of Christendom we now know as romance at court, and chivalry between the nobles. It was important for him to reconcile himelf with his churchmen, the noblemen and commoners alike. He certainly made an effort in England; more or less with success.

It is hard to conclude if Canute's attitude towards the Church came out of deep religious devotion, or merely as a means to proliferate his regime's hold on the people. It was probably a bit of a mix. We find evidence of a respect for the Viking religion in his praise poetry, which he was happy enough for his skalds to embellish in Norse mythology, while other Viking leaders were insistant on the rigid observation of the Chritian line, like St Olaf.[82] We see too the desire for a respectable Chritian nationhood within Europe. In 1018, some sources suggest he was at Canterbury on the return of its Archbishop Lyfing from Rome, to receive letters of exhortation from the Pope.[83] If this chronology is correct, he probably went from Canturbury to the Witan at Oxford, with Archbishop Wulfstan of York in attendance to record the event.[84] Canute surely saw he was in a potentially useful state of affairs, as far as the Church could be held. With its status as the keeper of the people's health, and the state's general welfare, it was a win-win situation.

His treatment of the Church, could not have been kinder. Canute not only repaired all the English churches and monasteries that were victims of the Viking love for plunder, and refilled their coffers, but he also built new churches, and was a patron of monastic communities. His homeland of Denmark was after all a Christain nation on the rise, and the desire to enhance the religion still fresh. His gifts were widespread, and often exhuberant.[85] Commonly land was given, exemption from taxes, as well as relics. Christ Church, was probably given rights at the important port of Sandwich, as well as tax exemption, with confirmation in the placement of their charters on the altar.[86] while it got the relics of St Aelfheah,[87] which was at the displeasure of the people of London. Another see in the king's favour was Winchester, second only to the Canturbury see in terms of its wealth.[88] New Minster's Liber Vitae records Canute as a benefactor of the monastery,[89] and the Wichester Cross (see image), with 500 marks of silver and 30 marks of gold in, as well as relics of various saints[90] was given to it. Old Minster was the recipient of a shrine for the relics of St Birinus, and the probable confirmation of its privilages.[91] The monastery at Evesham, with its Abbot Aelfweard purportedly a relative of the king, through Aelgifu the Lady (probably Aelfgifu of Northampton, rather than Queen Emma, also known as Aelfgifu), the ruler of the monastery, got the relics of St Wigstan.[92] Canute's generosity towards his subjects, a thing his skalds called destroying treasure,[93] was of course popular with the English. Still, it is important to remember, not all Englishmen were in his favour, and the burden of taxation was widely felt.[94] His attitude towards London's see was clearly not benign. The monasteries at Ely and Glastonbury were not it seems on good terms either. Other gifts were also given to his neighbours. Among these were a gift to Chartres, of which its bishiop wrote; When we saw the gift that you sent us, we were amazed at your knowledge as well as your faith... since you, whom we had heard to be a pagan prince, we now know to be not only a Chritian, but also a most generous donor to God's churches and servants.[95] He is known to have sent a psalter and sacramentary made in Peterborough, famous for its illustrations to Cologne,[96] and a book written in gold, among other gifts, to William the Great of Aquitaine.[97] This golden book was apparently to support Aquitanian claims St Martial, patron saint of Aquitaine was an apostle.[98] Of some consequnce, its recipient was an avid artisan, scholar, and devout Christian, and the Abbey of Saint-Martial was a great library and scriptorium, second only to the one at Cluny. It is probable Canute's gifts were well beyond anything we can now prove.[99]

Canute’s journey to Rome in 1027 is another sign of his dedication to the Christian religion. It may be he went to attend Emperor Conrad II’s coronation in order to improve relations between the two powers, yet he had made a vow previously to seek the favour of St Peter, the keeper of the keys to the heavenly kingdom.[100] While in Rome, Canute got an agreement from the Pope to reduce the fees paid by the English archbishops to receive their pallium. He also arranged for the travelers of his realm that they should pay reduced or no tolls, and that they should be safeguarded on their way to and from Rome. Some evidence exists for a second journey in 1030.[101]

Succession

Canute died in 1035, at Shaftesbury, in Dorset. He was buried in Old Minster, at Winchester. After the Norman Conquest the new regime was keen to signal its arrival by an ambitious programme of grandiose cathedrals and castles in England. Winchester Cathedral was built on the old Anglo-Saxon site. Canute's bones, along with Emma of Normandy's and Harthacanute's, were set in mortuary chests. During the English Civil War, in the 17th century, plundering soldiers scattered the bones on the floor, and they were spread amongst the various chests thereafter, along with those of other English kings and queens, such as king Edwy and his queen Elgiva, and William Rufus.

His daughter was set to marry Conrad II's son Henry III eight months after his death.[102]

On his death Canute was succeeded in Denmark by Harthacanute, reigning as Canute III. Harold Harefoot laid claim to the throne in England until his death in 1040. Harthacanute was to reunite the two crowns of Denmark and England until his death in 1042. Canute's line came to an end, although his legacy did not. The house of Wessex was to reign again in Edward the Confessor, whom Harthacanute had brought out of exile in Normandy and made treaty with. It meant the throne was Edward's if he died with no legitimate male heir. Edward was crowned King, and the Norman influence at Court was on the rise: pure Viking and Anglo-Saxon influence in England was past, although it should be remembered that the Normans themselves were of Viking descent.

Marriages and issue

- 1 - Aelgifu of Northampton

- Sweyn Knutsson, Viceroy of Norway

- Harold Harefoot, King of England

- 2 - Emma of Normandy

- Harthacanute, King of Denmark and England

- Gunhilda of Denmark, wed Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor.

Family tree

| Harald Bluetooth |

|

|

Mieszko |

|

Dubrawka |

|

William |

|

Sprota | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Sweyn |

|

Gunhilda |

|

|

|

Gunnora |

|

Richard | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aelgifu of Northampton |

|

Canute |

|

Emma of Normandy |

|

Ethelred the Unready |

|

Aelflaed, 1st wife |

|

|

|

Richard |

|

Judith | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweyn Knutsson |

|

Harold Harefoot |

|

|

Gunhilda of Denmark |

|

|

Alfred Aetheling |

|

Edmund II |

|

Ealdgyth |

|

Robert |

|

Herleva | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gytha Thorkelsdóttir+ |

|

Godwin, Earl of Wessex |

|

Harthacanute |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Edward |

|

Agatha |

|

William |

|

Matilda | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweyn |

|

Harold II |

|

Tostig |

|

|

Edith |

|

Edward the Confessor |

|

Edgar Ætheling |

|

|

|

|

|

Cristina |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gyrth, Gunnhilda, Aelfgifu, Leofwine & Wulfnoth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malcolm |

|

Margaret |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other children |

|

Edith of Scotland |

|

Henry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

+Said to have been a great-granddaughter of Canute's grandfather Harald Bluetooth, but this was probably a fiction intended to give her a royal bloodline.

Ancestry

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16. Harthacnut of Denmark | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

8. Gorm the Old |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

4. Harald I of Denmark |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

18. Harald Klak | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

9. Thyra |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

2. Sweyn Forkbeard |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

5. Gyrid Olafsdottir |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

1. Canute |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

24. Lestko | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

12. Siemomysł |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

6. Mieszko I of Poland |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

3. Sigrid the Haughty |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

28. Vratislaus I, Duke of Bohemia | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

14. Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

29. Drahomíra | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

7. Dubrawka of Bohemia |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

Ruler of the waves

Henry of Huntingdon, the 12th century chronicler, tells how Canute set his throne by the sea shore and commanded the tide to halt and not wet his feet and robes; but the tide failed to stop. According to Henry, Canute leapt backwards and said 'Let all men know how empty and worthless is the power of kings, for there is none worthy of the name, but He whom heaven, earth, and sea obey by eternal laws'. He then hung his gold crown on a crucifix, and never wore it again.[103]

This story may be apocryphal. While the contemporary Encomium Emmae has no mention of it, it would seem that so pious a dedication might have been recorded there, since the same source gives an 'eye-witness account of his lavish gifts to the monasteries and poor of St Omer when on the way to Rome, and of the tears and breast-beating which accompanied them'.[104] Goscelin, writing later in the 11th century, instead has Canute place his crown on a crucifix at Winchester one Easter, with no mention of the sea, and 'with the explanation that the king of kings was more worthy of it than he'.[105] However there may be a 'basis of fact, in a planned act of piety,' behind this story, and Henry of Huntingdon cites it as an example of the king's 'nobleness and greatness of mind'.[106] Later historians repeated the story, most of them adjusting it to have Canute more clearly aware that the tides would not obey him, and staging the scene to rebuke the flattery of his courtiers; and there are earlier Celtic parallels in stories of men who commanded the tides, namely Saint Illtud, Maelgwn, king of Gwynedd, and Tuirbe, of Tuirbe's Strand, in Brittany.[107]

The encounter with the waves is said to have taken place at Bosham in West Sussex, or Southampton in Hampshire.

According to the House of Commons Information Office (The Palace of Westminster Factsheet G11, General Series Revised March 2008), Canute set up a Royal palace during his reign on Thorney Island (later to become known as Westminster) as the area was sufficiently far away from the busy settlement to the east known as London. It is believed that, on this site, Canute tried to command the tide of the river to prove to his courtiers that they were fools to think that he could command the waves.

See also

- The Viking Age

- The Raven banner

Notes on the text

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, pp. 95–98.

- ↑ Graslund, B.,'Knut den store och sveariket: Slaget vid Helgea i ny belysning', Scandia, vol. 52 (1986), pp. 211–238.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, pp. 0-260

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 97.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, p. 196.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 197-198

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 202 & 206.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp.196-197, 201-202 & 272

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 197-198 & 202.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 197-198 & 202.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Encomiast, Encomium Emmae, ii. 2, pg. 18

- ↑ Thietmar, Chronicon, vii. 39, pgs. 446-447

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 40.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 44.

- ↑ Douglas, English Historical Documents, pp. 335-336

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 160.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 92.

- ↑ John, H., The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings, Penguin (1995), p. 122.

- ↑ Sawyer, History of the Vikings, pp. 171

- ↑ Sawyer, History of the Vikings, pp. 171

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 27

- ↑ Sawyer, History of the Vikings, pp. 171

- ↑ Sawyer, History of the Vikings, pp. 171

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 27

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. ???.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. ???.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. ???.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 27.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 57.

- ↑ Garmonsway, G.N. (ed. & trans.), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Dent Dutton, 1972 & 1975, Peterborough (E) text, s.a. 1015, p. 146.

- ↑ Campbell, A. (ed. & trans.), Encomium Emmae Reginae, Camden 3rd Series vol.LXXII, 1949, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ G. Jones, Vikings, p. 370

- ↑ G. Jones, Vikings, p. 370

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 57.

- ↑ G. Jones, Vikings, p. 370

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 59.

- ↑ G. Jones, Vikings, p. 371

- ↑ G. Jones, Vikings, p. 371

- ↑ G. Jones, Vikings, p. 371

- ↑ Williams, A., Æthelred the Unready The Ill-Counselled King, Hambledon & London, 2003, pp. 146–7.

- ↑ Forte, Oram & Pedersen, Viking Empires, pp. 198

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.86

- ↑ Lawson, cnut, p.162

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 89.

- ↑ Thietmar, Chronicon, vii. 7, pp.502-03

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 90.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, pp.168-69.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 198

- ↑ Jones, Vikings, p.373

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, pp. 95–98.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p.197.

- ↑ Adam of Bremen, Gesta Daenorum, ii.61, p. 120.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. ???.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, pp. ??

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, pp. 197.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 196-197

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, pp. 65-66.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 97.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, pp. 124-125.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 193.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 193.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 193.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 125

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 198.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 189.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 189.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 104.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 191.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 191.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p. 193.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp.197-198.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut. pp. 102.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, pp. 197-198.

- ↑ Forte, et al., Viking Empires, pp. 198.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 102.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 103.

- ↑ Lausavisur, ed. Johson Al, pgs. 269-270

- ↑ Ranelagh, A Short History of Ireland, p.31

- ↑ Encomiast, Encomium Emmae, ii. 19, pg 34

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 103.

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p.129

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, P.86

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, P.87

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, pp.139-147

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, P.87

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.141

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.142

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.142

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.126

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.142

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.143

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p.128

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.147

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.142

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.146

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.146

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.144

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.146

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p.145

- ↑ Trow, Cnut, p.186

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 98 & pp. 104-105.

- ↑ Forester, T. (ed. & trans.), The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon, Bohn, 1853 (reprinted Llanerch, 1991), p. 199.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 133.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 134.

- ↑ Lawson, Cnut, p. 133; Forester, , pp. 198-9.

- ↑ Lord Raglan: "Canute and the Waves": Man, Vol. 60, (Jan., 1960), pp. 7-8.

References

- Campbell (ed), Encomium

- Forte, A. (2005), Viking Empires (1st ed.), Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82992-5

- Godsell, Andrew "King Canute and the Advancing Tide", "History For All" magazine 2002, republished in "Legends of British History" 2008 ISBN 978-0951557334

- Jones, G (1984), A History of the Vikings (2nd ed.), Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-285139-X

- Lawson, M. K. (2004), Cnut: England's Viking King (2nd ed.), Stroud: Tempus, ISBN 0-7524-2964-7

- Ranelagh, John O'Beirne (2001). A Short History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521469449.

- Sawyer, P. (1997), The Oxford Ils. History of the Vikings (1st ed.), Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820526-0

- Swanton, Michael, ed. (1996), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-92129-5

- Thietmar, Chronicon

- Trow, M. J. (2005), Cnut: Emperor of the North, Stroud: Sutton, ISBN 0-7509-3387-9

External links

- Canute the Great

- Canute (Knud) The Great - From Viking warrior to English king

- Vikingworld (Danish) - Canute the Great (Knud den Store)

- Cnut the Great: Emperor of the North

- Time Team - Who was King Cnut?

- Canute the Great At Find A Grave

- Northvegr (Scanidinavian) - A History of the Vikings (Search)

- Canute Or Cnut from the Online Encyclopedia

- Monarchies of Britain: Danish Kings of England

- Images out of the British Library

|

Canute the Great

Born: c. 995 Died: 1035 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edmund Ironside |

King of England 1016-1035 |

Succeeded by Harold Harefoot |

| Preceded by Harald II |

King of Denmark 1018-1035 |

Succeeded by Harthacanute |

| Preceded by Olaf the Saint |

King of Norway 1028-1035 with Hákon Eiríksson (1028-1029) Sveinn Alfífuson (1030-1035) |

Succeeded by Magnus the Good |

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Canute the Great |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Canute I; Cnut |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | English monarch |

| DATE OF BIRTH | circa 995 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Denmark |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1035 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | England |