Buoyancy

In physics, buoyancy (BrE IPA: /ˈbɔɪənsi/) is the upward force on an object produced by the surrounding liquid or gas in which it is fully or partially immersed, due to the pressure difference of the fluid between the top and bottom of the object. The net upward buoyancy force is equal to the magnitude of the weight of fluid displaced by the body. This force enables the object to float or at least seem lighter. Buoyancy is important for many vehicles such as boats, ships, balloons, and airships, and plays a role in diverse natural phenomena such as sedimentation.

Contents |

Archimedes' principle

It is named after Archimedes of Syracuse, who first discovered this law. According to Archimedes' principle, "Any object, wholly or partly immersed in a fluid, is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object."

Vitruvius (De architectura IX.9–12) recounts the famous story of Archimedes making this discovery while in the bath. He was given the task of finding out if a goldsmith, who worked for the king, was carefully replacing the king's gold with silver. While doing this Archimedes decided he should take a break so went to take a bath. While entering the bath he noticed that when he placed his legs in, water spilled over the edge. Struck by a moment of realisation, he shouted "eureka!" He informed the king that there was a way to positively tell if the smith was cheating him. Knowing that gold has a higher density than silver, he placed the king's crown and a gold crown of equal weight into a pool. Since the king's crown caused more water to overflow and was therefore less dense, Archimedes concluded that it contained silver, causing the smith to be executed. The actual record of Archimedes' discoveries appears in his two-volume work, On Floating Bodies. The ancient Chinese child prodigy Cao Chong also applied the principle of buoyancy in order to accurately weigh an elephant, as described in the Sanguo Zhi.

Archimedes' principle does not consider the surface tension (capillarity) acting on the body.[1]

The weight of the displaced fluid is directly proportional to the volume of the displaced fluid (if the surrounding fluid is of uniform density). Thus, among completely submerged objects with equal masses, objects with greater volume have greater buoyancy.

Suppose a rock's weight is measured as 10 newtons when suspended by a string in a vacuum. Suppose that when the rock is lowered by the string into water, it displaces water of weight 3 newtons. The force it then exerts on the string from which it hangs would be 10 newtons minus the 3 newtons of buoyant force: 10 − 3 = 7 newtons. Buoyancy reduces the apparent weight of objects that have sunk completely to the sea floor. It is generally easier to lift an object up through the water than it is to pull it out of the water.

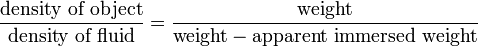

The density of the immersed object relative to the density of the fluid can easily be calculated without measuring any volumes:

Forces and equilibrium

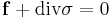

First of all lets calculate the pressure inside a fluid in equilibrium. The corresponding equilibrium equation is:

Where  is the force density exerted by some outer field on the fluid, and

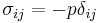

is the force density exerted by some outer field on the fluid, and  is the stress tensor. We know that in our case the stress tensor is proportional to the identity tensor:

is the stress tensor. We know that in our case the stress tensor is proportional to the identity tensor:  . Here

. Here  is the kronecker delta symbol. Using this the above equation becomes:

is the kronecker delta symbol. Using this the above equation becomes:

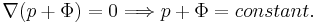

Now lets assume that the outer force field is conservative, that is it can be written as the negative gradient of some scalar valued function: : . Hence we have:

. Hence we have:

As we see, we got that the shape of the open surface of a fluid equals the equipotential plane of the applied outer conservative force field. Now lets put the z axis pointing downwards. In our case we have gravity, so  where g is the gravitational acceleration,

where g is the gravitational acceleration,  is the mass density of the fluid. Let the constant be zero, that is the pressure zero where z is zero. So the pressure inside the fluid, when it is subject to gravity:

is the mass density of the fluid. Let the constant be zero, that is the pressure zero where z is zero. So the pressure inside the fluid, when it is subject to gravity:

So as we see pressure, increases with depth below the surface of a liquid, as z denotes the distance from the surface of the liquid into it. Any object with a non-zero vertical depth will have different pressures on its top and bottom, with the pressure on the bottom being greater. This difference in pressure causes the upward buoyancy forces.

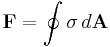

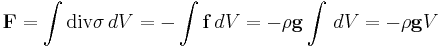

The buoyant force exerted on a body can now be calculated easily, since we know the internal pressure of the fluid. We know that the force exerted on the body can be calculated by integrating the stress tensor over the surface of the body:

The surface integral can be transformed into a volume integral with the help of the Gauss-Ostrogradskij theorem :

Where V is obviously the measure of the volume in contact with the fluid, that is the volume of the submerged part of the body. Since the fluid doesnt exert force on the part of the body which is outside of it.

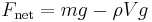

The magnitude of buoyant force may be appreciated a bit more from the following argument. Consider any object of arbitrary shape and volume V surrounded by a liquid. . The force the liquid exerts on an object within the liquid is equal to the weight of the liquid with a volume equal to that of the object. This force is applied in a direction opposite to gravitational force that is, of magnitude:

, where

, where  is the density of the liquid,

is the density of the liquid,  is the volume of the body of liquid , and

is the volume of the body of liquid , and  is the gravitational acceleration at the location in question.

is the gravitational acceleration at the location in question.

Now, if we replace this volume of liquid by a solid body of the exact same shape, the force the liquid exerts on it must be exactly the same as above. In other words the "buoyant force" on a submerged body is directed in the opposite direction to gravity and is equal in magnitude to :

The net force on the object is thus the sum of the buoyant force and the object's weight

If the buoyancy of an (unrestrained and unpowered) object exceeds its weight, it tends to rise. An object whose weight exceeds its buoyancy tends to sink.

Commonly, the object in question is floating in equilibrium and the sum of the forces on the object is zero, therefore;

and therefore;

showing that the depth to which a floating object will sink (its "buoyancy") is independent of the variation of the gravitational acceleration at various locations on the surface of the Earth.

- (Note: If the liquid in question is seawater, it will not have the same density (

) at every location. For this reason, a ship may display a Plimsoll line.)

) at every location. For this reason, a ship may display a Plimsoll line.)

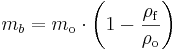

It is common to define a buoyant mass mb that represents the effective mass of the object with respect to gravity

where  is the true (vacuum) mass of the object, whereas ρo and ρf are the average densities of the object and the surrounding fluid, respectively. Thus, if the two densities are equal, ρo = ρf, the object appears to be weightless. If the fluid density is greater than the average density of the object, the object floats; if less, the object sinks.

is the true (vacuum) mass of the object, whereas ρo and ρf are the average densities of the object and the surrounding fluid, respectively. Thus, if the two densities are equal, ρo = ρf, the object appears to be weightless. If the fluid density is greater than the average density of the object, the object floats; if less, the object sinks.

Compressive fluids

The atmosphere's density depends upon altitude. As an airship rises in the atmosphere, its buoyancy decreases as the density of the surrounding air decreases. As a submarine expels water from its buoyancy tanks (by pumping them full of air) it rises because its volume is constant (the volume of water it displaces if it is fully submerged) as its weight is decreased.

Compressible objects

As a floating object rises or falls, the forces external to it change and, as all objects are compressible to some extent or another, so does the object's volume. Buoyancy depends on volume and so an object's buoyancy reduces if it is compressed and increases if it expands.

If an object at equilibrium has a compressibility less than that of the surrounding fluid, the object's equilibrium is stable and it remains at rest. If, however, its compressibility is greater, its equilibrium is then unstable, and it rises and expands on the slightest upward perturbation, or falls and compresses on the slightest downward perturbation.

Submarines rise and dive by filling large tanks with seawater. To dive, the tanks are opened to allow air to exhaust out the top of the tanks, while the water flows in from the bottom. Once the weight has been balanced so the overall density of the submarine is equal to the water around it, it has neutral buoyancy and will remain at that depth. Normally, precautions are taken to ensure that no air has been left in the tanks. If air were left in the tanks and the submarine were to descend even slightly, the increased pressure of the water would compress the remaining air in the tanks, reducing its volume. Since buoyancy is a function of volume, this would cause a decrease in buoyancy, and the submarine would continue to descend.

The height of a balloon tends to be stable. As a balloon rises it tends to increase in volume with reducing atmospheric pressure, but the balloon's cargo does not expand. The average density of the balloon decreases less, therefore, than that of the surrounding air. The balloon's buoyancy reduces because the weight of the displaced air is reduced. A rising balloon tends to stop rising. Similarly, a sinking balloon tends to stop sinking.

Density

If the weight of an object is less than the weight of the fluid the object would displace if it were fully submerged, then the object has an average density less than the fluid and has a buoyancy greater than its weight. If the fluid has a surface, such as water in a lake or the sea, the object will float at a level where it displaces the same weight of fluid as the weight of the object. If the object is immersed in the fluid, such as a submerged submarine or air in a balloon, it will tend to rise. If the object has exactly the same density as the fluid, then its buoyancy equals its weight. It will tend neither to sink nor float. An object with a higher average density than the fluid has less buoyancy than weight and it will sink. A ship floats because, although it is made of steel, which is denser than water, it encloses a volume of air and the resulting shape has an average density less than that of the water.

See also

- Buoy

- Buoyancy compensator

- Cartesian diver

- Diving weighting system

- Hydrostatics

- Hull (ship)

- Hydrometer

- Lighter than air

- Naval architecture

- Pontoon

- Quicksand

- Salt fingering

- Submarine

- Thrust

- Plimsoll line

References

- ↑ "Floater clustering in a standing wave: Capillarity effects drive hydrophilic or hydrophobic particles to congregate at specific points on a wave" (PDF) (2005-06-23).

External links

- Falling in Water (Animation 1)

- Falling in Water (Animation 2)

- Falling in Water

- Buoyancy & Density - Video

- Archimedes' Principle - background and experiment