New York Central Railroad

| New York Central Railroad | |

|---|---|

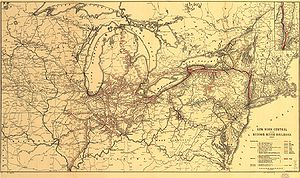

New York Central system as of 1918 |

|

| Reporting marks | NYC |

| Locale | Northeast to Midwest |

| Dates of operation | 1831–1968 |

| Successor | Penn Central |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8½ in (1,435 mm) (standard gauge) |

| Headquarters | New York City |

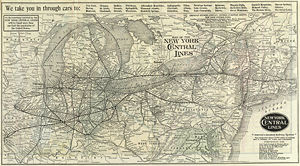

The New York Central Railroad (AAR reporting marks NYC), known simply as the New York Central in its publicity, was a railroad operating in the Northeastern United States. Headquartered in New York, the railroad served most of the Northeast, including extensive trackage in the states of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Massachusetts, plus additional trackage in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. Its primary connections included Chicago and Boston. The NYC's Grand Central Terminal in New York City is one of its best known extant landmarks.

In 1968 the NYC merged with its former rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, to form Penn Central (the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad joined in 1969). That company soon went bankrupt and was taken over by the federal government and merged into Conrail in 1976. Conrail was broken up in 1998, and portions of its system was transferred to the newly-formed New York Central Lines LLC, a subsidiary leased to, and eventually absorbed by CSX. That company's lines included the original New York Central main line, but outside that area it included lines that were never part of the NYC system.

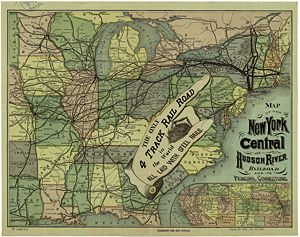

The famous Water Level Route of the NYC, from New York City to upstate New York, was the first four-track long-distance railroad in the world.

Contents |

History

Pre-New York Central: 1826-1853

The oldest part of the NYC was the first permanent railroad in the state of New York and one of the first railroads in the United States. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was chartered in 1826 to connect the Mohawk River at Schenectady to the Hudson River at Albany, providing a way for freight and especially passengers to avoid the extensive and time-consuming locks on the Erie Canal between Schenectady and Albany. The Mohawk and Hudson opened on September 24, 1831, and changed its name to the Albany and Schenectady Railroad on April 19, 1847.

The Utica and Schenectady Railroad was chartered April 29, 1833; as the railroad paralleled the Erie Canal it was prohibited from carrying freight. Revenue service began August 2, 1836, extending the line of the Albany and Schenectady Railroad west from Schenectady along the north side of the Mohawk River, opposite the Erie Canal, to Utica. On May 7, 1844 the railroad was authorized to carry freight with some restrictions, and on May 12, 1847 the ban was fully dropped, but the company still had to pay the equivalent in canal tolls to the state.

The Syracuse and Utica Railroad was chartered May 1, 1836 and similarly had to pay the state for any freight displaced from the canal. The full line opened July 3, 1839, extending the line further to Syracuse via Rome (and further to Auburn via the already-opened Auburn and Syracuse Railroad). This line was not direct, going out of its way to stay near the Erie Canal and serve Rome, and so the Syracuse and Utica Direct Railroad was chartered January 26, 1853. Nothing of that line was ever built, though the later West Shore Railroad, acquired by the NYC in 1885, served the same purpose.

The Auburn and Syracuse Railroad was chartered May 1, 1834 and opened mostly in 1838, the remaining 4 miles (6 km) opening on June 4, 1839. A month later, with the opening of the Syracuse and Utica Railroad, this formed a complete line from Albany west via Syracuse to Auburn, about halfway to Geneva. The Auburn and Rochester Railroad was chartered May 13, 1836 as a further extension via Geneva and Canandaigua to Rochester, opening on November 4, 1841. The two lines merged on August 1, 1850 to form the rather indirect Rochester and Syracuse Railroad (known later as the Auburn Road). To fix this, the Rochester and Syracuse Direct Railroad was chartered and immediately merged into the Rochester and Syracuse on August 6, 1850. That line opened June 1, 1853, running much more directly between those two cities, roughly parallel to the Erie Canal.

To the west of Rochester, the Tonawanda Railroad was chartered April 24, 1832 to build from Rochester to Attica. The first section, from Rochester southwest to Batavia, opened May 5, 1837, and the rest of the line to Attica opened on January 8, 1843. The Attica and Buffalo Railroad was chartered in 1836 and opened on November 24, 1842, running from Buffalo east to Attica. When the Auburn and Rochester Railroad opened in 1841, there was no connection at Rochester to the Tonawanda Railroad, but with that exception there was now an all-rail line between Buffalo and Albany. On March 19, 1844 the Tonawanda Railroad was authorized to build the connection, and it opened later that year. The Albany and Schenectady Railroad bought all the baggage, mail and emigrant cars of the other railroads between Albany and Buffalo on February 17, 1848 and began operating through cars.

On December 7, 1850 the Tonawanda Railroad and Attica and Buffalo Railroad merged to form the Buffalo and Rochester Railroad. A new direct line opened from Buffalo east to Batavia on April 26, 1852, and the old line between Depew (east of Buffalo) and Attica was sold to the Buffalo and New York City Railroad on November 1. The line was added to the New York and Erie Railroad system and converted to the Erie's 6 foot (1829 mm) broad gauge.

The Schenectady and Troy Railroad was chartered in 1836 and opened in 1842, providing another route between the Hudson River and Schenectady, with its Hudson River terminal at Troy.

The Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad was chartered in 1834 to build from Lockport on the Erie Canal west to Niagara Falls; it opened in 1838. On December 14, 1850 it was reorganized as the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad, and an extension east to Rochester opened on July 1, 1852.

The Buffalo and Lockport Railroad was chartered April 27, 1852 to build a branch of the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls from Lockport towards Buffalo. It opened in 1854, running from Lockport to Tonawanda, where it joined the Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad, opened 1837, for the rest of the way to Buffalo.

In addition to the Syracuse and Utica Direct, another never-built company, the Mohawk Valley Railroad, was chartered January 21, 1851 and reorganized December 28, 1852, to build a railroad on the south side of the Mohawk River from Schenectady to Utica, next to the Erie Canal and opposite the Utica and Schenectady. The West Shore Railroad was later built on that location.

Albany industrialist and Mohawk Valley Railroad owner Erastus Corning got the above railroads together into one system, and on March 17, 1853 they agreed to merge. The merger was approved by the state legislature on April 2, and ten of the remaining companies merged to form the New York Central Railroad on May 17, 1853. The following companies were consolidated into this system, including the main line from Albany to Buffalo:

- Albany and Schenectady Railroad

- Utica and Schenectady Railroad

- Syracuse and Utica Railroad

- Rochester and Syracuse Railroad

- Buffalo and Rochester Railroad

- The Rochester and Syracuse also owned the old alignment via Auburn, Geneva and Canandaigua, known as the "Auburn Road". The Buffalo and Rochester included a branch from Batavia to Attica, part of the main line until 1852. Also included in the merger were three other railroads:

- Schenectady and Troy Railroad, a branch from Schenectady east to Troy

- Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad, a major branch from Rochester west to Niagara Falls

- Buffalo and Lockport Railroad, a branch from the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls at Lockport south to Buffalo via trackage rights on the Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad from Tonawanda

- As well as two that had not built any road, and never would:

- Mohawk Valley Railroad

- Syracuse and Utica Direct Railroad

Soon the Buffalo and State Line Railroad and Erie and North East Railroad converted to standard gauge from 6 foot (1829 mm) broad gauge and connected directly with the NYC in Buffalo, providing a through route to Erie, Pennsylvania.

Erastus Corning years: 1853-1867

The Rochester and Lake Ontario Railroad was organized in 1852 and opened in Fall 1853; it was leased to the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad, which became part of the NYC, before opening. In 1855 it was merged into the NYC, providing a branch from Rochester north to Charlotte on Lake Ontario.

The Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad was also merged into the NYC in 1855. It had been chartered in 1834 and opened in 1837, providing a line between Buffalo and Niagara Falls. It was leased to the NYC in 1853.

Also in 1855 came the merger with the Lewiston Railroad, running from Niagara Falls north to Lewiston. It was chartered in 1836 and opened in 1837 without connections to other railroads. In 1854 a southern extension opened to the Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad and the line was leased to the NYC.

The Canandaigua and Niagara Falls Railroad was chartered in 1851. The first stage opened in 1853 from Canandaigua on the Auburn Road west to Batavia on the main line. A continuation west to North Tonawanda opened later that year, and in 1854 a section opened in Niagara Falls connecting it to the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge. The NYC bought the company at bankruptcy in 1858 and reorganized it as the Niagara Bridge and Canandaigua Railroad, merging it into itself in 1890.

The Saratoga and Hudson River Railroad was chartered in 1864 and opened in 1866 as a branch of the NYC from Athens Junction, southeast of Schenectady, southeast and south to Athens on the west side of the Hudson River. On September 9, 1867 the company was merged into the NYC, but in 1867 the terminal at Athens burned down and the line was abandoned. In the 1880s the New York, West Shore and Buffalo Railway leased the line and incorporated it into their main line, taken over by the NYC in 1885 as the West Shore Railroad.

The Hudson River Railroad

- See West Side Line for details on the section in Manhattan and Hudson Line for current Metro-North Railroad operations south of Poughkeepsie.

The Troy and Greenbush Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened later that year, connecting Troy south to East Albany on the east side of the Hudson River. The Hudson River Railroad was chartered May 12, 1846 to extend this line south to New York City; the full line opened October 3, 1851. Prior to completion, on June 1, the Hudson River leased the Troy and Greenbush.

Cornelius Vanderbilt obtained control of the Hudson River Railroad in 1864, soon after he bought the parallel New York and Harlem Railroad.

Along the line of the Hudson River Railroad, the High Line was built in the 1930s in New York City as an elevated bypass to the existing street running trackage on Eleventh Avenue, at the time called "Death Avenue" due to the large number of accidents involving trains. The elevated section has since been abandoned, and the tunnel to the north, built at the same time, is used only by Amtrak trains to New York Penn Station (all other trains use the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad to access the New York and Harlem Railroad). A surviving section of the High Line, in the Chelsea section of Manhattan, is currently under development as a linear park.

Vanderbilt years: 1867-1954

In 1867 Vanderbilt acquired control of the NYC, with the help of maneuverings related to the Hudson River Bridge in Albany. On November 1, 1869 he merged the NYC with his Hudson River Railroad into the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. This extended the system south from Albany along the east bank of the Hudson River to New York City, with the leased Troy and Greenbush Railroad running from Albany north to Troy.

Vanderbilt's other lines were operated as part of the NYC; these included the New York and Harlem Railroad, Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, Canada Southern Railway and Michigan Central Railroad.

The Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad was chartered in 1869 and opened in 1871, providing a route on the north side of the Harlem River for trains along the Hudson River to head southeast to the New York and Harlem Railroad towards Grand Central Terminal or the freight facilities at Port Morris. From opening it was leased by the NYC.

The Geneva and Lyons Railroad was organized in 1877 and opened in 1878, leased by the NYC from opening. This was a north-south connection between Syracuse and Rochester, running from the main line at Lyons south to the Auburn Road at Geneva. It was merged into the NYC in 1890.

On July 1, 1900, the Boston and Albany Railroad was leased by the NYC, although it retained a separate identity. In 1914 the name was changed again, forming the modern New York Central Railroad.

The Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway, also known as the Big Four was formed on June 30, 1889 by the merger of the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis Railway, the Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis and Chicago Railway and the Indianapolis and St. Louis Railway. The following year, the company gained control of the former Indiana Bloomington and Western Railway. By 1906, the Big Four was itself acquired by the New York Central Railroad.

The NYC had a distinctive character different from its arch rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad and its mountainous terrain. The NYC was best known as the Water Level Route; most of its major routes, including New York to Chicago, followed rivers and had no significant grades. This influenced many things, including advertising and most notably locomotive design.

Steam locomotives of the NYC were optimized for speed on that flat raceway of a main line, rather than slow mountain lugging. Famous locomotives of the system included the well-known 4-6-4 Hudsons, particularly the 1937-38 J-3as; 4-8-2 WWII-era L-3 and L-4 Mohawks; and the postwar Niagaras: fast 4-8-4 locomotives often considered the epitome of their breed by steam locomotive aficionados.

Despite having some of the most modern steam locomotives anywhere, the NYC dieselized rapidly, conscious of its by-then difficult financial position and the potential relief that more economical diesel-electric power could bring. Very few NYC steam locomotives still exist, due to then-NYC high executive Alfred E. Perlman's total lack of sympathy for historic preservation of NYC's finest steam. All Hudsons and Niagaras were sent to the scrapper's torch by 1956. In 2008, the only surviving big steam locomotives are two 4-8-2 Mohawk locomotives: L-2d Mohawk #2933 (at the National Museum of Transport in St. Louis, Missouri) and dual-purpose, modern L-3a Mohawk #3001 (at the National New York Central Railroad Museum in Elkhart, Indiana). The story of their survival is a fascinating one: L-2d #2933 was somehow overlooked during the 1956-57 scrapping process, and was literally hidden for years after this by sympathetic NYC employees at the NYC's Selkirk Yard, New York roundhouse, behind large boxes. In January 1962, when scrapping her would have been a public-relations disaster, she was donated to the St. Louis museum. Since the last NYC steam locomotive operated in New York State on August 7, 1953, her survival defies credibility. As for the only modern WWII-era NYC steam locomotive to survive, L-3a #3001 (built in 1940), she was sold by the NYC to the City of Dallas, Texas in 1957, to replace a Texas & Pacific locomotive which had been heavily vandalized in a city park. Much later, the National New York Central Railroad Museum traded a Pennsylvania Railroad GG1 electric locomotive for her. She is reportedly in very good condition, and would make a wonderful candidate for restoration to operating condition if suitable trackage existed for her operation.

The financial situation of northeastern railroading then became so dire that not even the economies of the new diesel-electric locomotives could change things.

Bypasses

A number of bypasses and cutoffs were built around congested areas.

The Junction Railroad's Buffalo Belt Line opened in 1871, providing a bypass of Buffalo, New York to the northeast, as well as a loop route for passenger trains via downtown. The West Shore Railroad, acquired in 1885, provided a bypass around Rochester, New York. The Terminal Railway's Gardenville Cutoff, allowing through traffic to bypass Buffalo to the southeast, opened in 1898.

The Schenectady Detour consisted of two connections to the West Shore Railroad, allowing through trains to bypass the steep grades at Schenectady, New York. The full project opened in 1902. The Cleveland Short Line Railway built a bypass of Cleveland, Ohio, completed in 1912. In 1924, the Alfred H. Smith Memorial Bridge was constructed as part of the Hudson River Connecting Railroad's Castleton Cut-Off, a 27.5-mile-long freight bypass of the congested Albany terminal area.

An unrelated realignment was made in the 1910s at Rome, when the Erie Canal was realigned and widened onto a new alignment south of downtown Rome. The NYC main line was shifted south out of downtown to the south bank of the new canal. A bridge was built southeast of downtown, roughly where the old main line crossed the path of the canal, to keep access to Rome from the southeast. West of downtown, the old main line was abandoned, but a brand new railroad line was built, running north from the NYC main line to the NYC's former Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburg Railroad, allowing all NYC through traffic to bypass Rome.

Trains

For most of the twentieth century the New York Central was known to have some of the most famous train routes in the United States. Its 20th Century Limited, begun in 1902, ran from Grand Central Terminal in New York to LaSalle Street Station Chicago and was its most famous train, known for its red carpet treatment and first class service. The Century, which followed the Water Level Route, could complete the 960.7-mile trip in just 16 hours after its June 15, 1938 streamlining (and did it in 15 1/2 hours for a short period after WWII). Also famous was its frequent Empire State Express service through upstate New York to Buffalo and Cleveland, and Ohio State Limited service from New York to Cincinnati. In addition to long distance service, the NYC also provided vital commuter service for residents of Westchester County, New York, along its Hudson, Harlem, and Putnam lines, into Manhattan.

Robert R. Young: 1954-1958

In June 1954, management of the New York Central System, lost a proxy fight in 1954 to Robert Ralph Young and the Alleghany Corporation he led. [1]

Alleghany Corporation was a real estate and railroad empire built by the Van Sweringen brothers of Cleveland in the 1920s and had notably controlled the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) and the Nickel Plate Road, before falling under the control of Young and financier Allan Price Kirby during the Great Depression.

R.R. Young was considered a railroad visionary, but found the failing New York Central was in worse shape than he had bargained for. Unable to keep his promises, Young was forced to suspend dividend payments in January 1958. He committed suicide later that month.

Alfred E. Perlman: 1958-1968

After his suicide, Young's role in NYC management was assumed by Alfred E. Perlman, who had been working with the NYC under Young since 1954. Although much had been accomplished to streamline NYC operations, in those tough economic times, mergers with other railroads were seen as the only possible road to financial stability.

Other mergers combined the Virginian Railway, Wabash Railroad, Nickel Plate Road, and several others into the Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W) system, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), Western Maryland Railroad (WM), and Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) combined with others to form the Chessie System.

By the mid-1960s, in the NYC's northeast operating area, the most likely suitor became the NYC's former arch-rival Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR).

In the mid-1960s, NYC experimented with 'Rocket Trains', building the M-497 Black Beetle (powered by jet engines stripped from an intercontinental bomber) as a potential solution to increasing car and aeroplane competition. While a technical success, the project did not leave prototype stage.

Penn Central, Conrail, CSX: 1968-present

The NYC became a fallen flag on February 1, 1968 when it joined with its old enemy, the Pennsylvania Railroad, in the ill-fated merger that produced Penn Central, soon saddled by the ICC with the additional burden of the money-losing New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, better known as the "New Haven."

Slightly over two years later, on June 21, 1970, the Penn Central Transportation Company filed for bankruptcy. The PC's transportation units operated in bankruptcy for over 5 years. Amtrak and local governmental agencies took over commuter, regional, and long-distance passenger operations during this period, eventually assuming ownership of the Northeast Corridor, a mostly-electrified route between Boston and Washington D.C. inherited primarily from the PRR and New Haven systems.

Conrail, officially the Consolidated Rail Corporation, was created by the U.S. Government to salvage Penn Central, and several other bankrupt railroads. On April 1, 1976, it began operations. Conrail achieved profitability by the 1990s and was sought by several other large railroads in a continuing trend of mergers.

On June 6, 1998, most of Conrail was split between Norfolk Southern and CSX. New York Central Lines LLC was formed as a subsidiary of Conrail, containing the lines to be operated by CSX; this included the old Water Level Route and many other lines of the New York Central, as well as various lines from other companies. It also assumed the NYC reporting mark. CSX eventually fully absorbed it, as part of a streamlining of Conrail operations.

See also

- 20th Century Limited

- Empire State Express

- Merchants Despatch

- David L. Gunn

- Kankakee Belt Route

- Ohio State Limited

- Xplorer

- New York Central Railroad Museum

- New York Central Tugboat 13

References

- Railroad History Database

- Surface Transportation Board Decision FD-33388, which created New York Central Lines LLC

- PRR Chronology

External links

- New York Central System Historical Society

- New York Architecture Images- The High Line

- A New York Central Railroad WebSite

- The Beginnings of the New York Central Railroad: The Consolidation

- Surviving Locomotives of the New York Central.

- New York Central in Western New York

- Albany Institute of History & Art

|

|||||||||||