Boxer Rebellion

| The Boxer Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

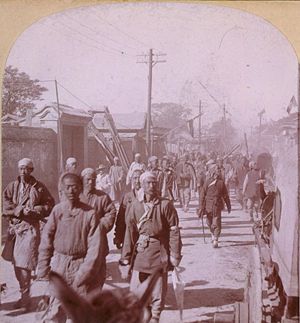

Boxer forces in Tianjin |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Eight-Nation Alliance (ordered by contribution):

|

Righteous Harmony Society (Boxers) |

||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 initially 49,000 total | 50,000–100,000 Boxers 70,000 Imperial troops |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,500 soldiers, 526 foreigners and Chinese Christians |

"All" Boxers, 20,000 Imperial troops |

||||||

| Civilians = 18,952+ | |||||||

|

|||||

The Boxer Rebellion, or more properly Boxer Uprising, was a violent anti-foreign, anti-Christian movement by the “Boxers United in Righteousness,” Yihe tuan [1] or Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists in China. In response to imperialist expansion, growth of cosmopolitan influences, and missionary arrogance, and against a background of state fiscal crisis and natural disasters, local organizations began to emerge in Shandong in 1898. These local groups attacked Catholic missionaries in Shandong in the summer of 1899 and gained strength on the slogan “Revive the Qing, destroy the foreign.” With the tacit approval of the court, Boxers across North China attacked mission compounds. They killed missionaries and Chinese Christians.

In the early summer of 1900, Boxer fighters, lightly armed and with little leadership, gathered in Beijing to besiege the foreign embassies. On June 21, the conservative faction of the Manchu Court induced the Empress Dowager, who ruled in the emperor’s name, to declare war on the foreign powers that had diplomatic representation in Beijing. Diplomats, foreign civilians, soldiers and some Chinese Christians retreated to the legation quarter where they held out for fifty-five days until the “Allies,” an eight nation coalition, brought 20,000 troops to their rescue. The Allied troops then conducted a campaign of indiscriminate slaughter, rape, and pillage. The Boxer Protocol of September 7, 1901 ended the uprising and provided for severe punishments, including an indemnity of 67 million pounds. [2] Subsequent reforms led, at least in part, to the end of the Qing Dynasty and the establishment of the Chinese Republic.

Contents |

The Origins of the Boxers

The Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists (traditional Chinese: 義和團; simplified Chinese: 义和团; pinyin: Yìhétuán) or the Boxer was a secret society founded in Shandong, a northern province of China. Westerners came to call well-trained, athletic young men "Boxers" due to the martial arts and calisthenics they practiced. Despite the obvious differences between Chinese Wushu and Western pugilistic boxing, the training for unarmed combat took on the same name to the Europeans. The Boxers believed that they could, through training, diet, martial arts, and prayer, perform extraordinary feats, such as flight and could become immune to swords and bullets. Further, they popularly claimed that millions of "spirit soldiers," would descend from the heavens and assist them in purifying China from foreign influences.

The name “Boxer Rebellion,” notes a recent study, is truly a “misnomer,” for the Boxers “never rebelled against the Manchu rulers of China and their Qing dynasty” and the “most common Boxer slogan" was “support the Qing, destroy the Foreign." Only after the movement was suppressed did both the foreign powers and influential Chinese officials realize that the Qing would have to remain as government of China. Therefore in order to save face for the Empress Dowager and the Manchu court, the fiction was created that the Boxers were rebels. The origin of the term “rebellion,” concludes one recent historian, was “purely political and opportunistic,” but it has shown a remarkable staying power, particularly in popular accounts. [3]

The gathering storm

One of the first signs of unrest appeared in a small village in Shandong province, where there had been a long dispute over the property rights of a temple between locals and the Roman Catholic authorities. The Catholics claimed that the temple was originally a church abandoned for decades after the Kangxi Emperor banned Christianity in China. The local court ruled in favor of the church, and angered villagers who claimed the temple for rituals. After the local authorities turned over the temple to the Catholics, the villagers (led by the Boxers) attacked the church building.

The exemption of missionaries from many laws further alienated local Chinese. In 1899, with the help of the French Minister in Peking, they obtained an edict granting official rank to each order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Local priests, by means of this official status, were able to support their people in legal disputes or family feuds and go over the heads of local officials. After the German government took over territory in Shandong, many Chinese feared that the missionaries, and by extension all Christians, were part of an imperialist attempt to "carve the melon," that is, to divide China and make it into colonies. [4]

The early months of the movement's growth coincided with the Hundred Days' Reform (11 June–21 September 1898). Reform officials persuaded the Guangxu Emperor to institute reforms which alienated many officials by their sweeping nature and led the Empress Dowager to step in and reverse the reforms. Making matters worse, massive floods in some areas and drought in others created poverty and refugees.

Now with a majority of conservatives in the Imperial Court, the Empress Dowager issued edicts in defense of the Boxers, drawing heated complaints from foreign diplomats in January, 1900. In June 1900 the Boxers, now joined by elements of the Imperial army, attacked foreign compounds in the cities of Tianjin and Peking. The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were all located on the Beijing Legation Quarter close to the Forbidden City in Peking. The legations were hurriedly linked into a fortified compound that became a refuge for foreign citizens in Peking. The Spanish and Belgian legations were a few streets away, and their staff were able to arrive safely at the compound. The German legation on the other side of the city was stormed before the staff could escape. When the Envoy for the German Empire, Klemens Freiherr von Ketteler, was murdered on 20 June by a Manchu banner man, the foreign powers demanded redress. On 21 June Empress Dowager Cixi declared war against all Western powers, but regional governors, including Li Hongzhang and Zhang Zhidong, quietly refused to cooperate. Shanghai's Chinese elite supported the provincial governors of southeastern China in resisting the imperial declaration of war.[5]

Missionaries murdered

- Missionary Herald, a BMS magazine, published letters and telegrams sent by priests and their families in Manchu Qing dynasty, in Shanxi province, Taiyuan city. In December 1900, Missionary Herald broke the news to its readers: Priests and their families were lured and cast into prison, then excecuted by the Manchu officials, "the entire mission staff in the Province of Shanxi has perished".

The murder of the BMS missionaries took place at the end of June 1900. The Taiyuan missionaries fled into a co-worker's house because Boxers were burning churches and houses, killing Christians and foreigners. Three days later, the Governor sent four deputies with soldiers, "promising to escort them in safety to the coast". Instead the missionaries were taken to a house near the Governor’s residence, were then "taken to the open space in front of the Governor’s residence, and stripped to the waist, as usual with those beheaded".[6]

- At 2005 English Professor Henry Hart released a book:Lost in the Gobi Desert to commemorate his great-grandfather's efforts to save the life of western missionaries and their Chinese followers from the hands of the Boxer rebels.

| “ | Boxers blamed “foreign devils” like my great-grandparents for causing northern China's drought and famine, exacerbating economic hardships by building railroads and telegraph lines (because such modern conveniences eliminated jobs), undermining the native textile industry with European imports, infecting and killing Chinese children with Christian prayers and for various other real and imagined infamies. | ” |

| “ | The murderous Boxer Rebellion came as a sudden thunderstorm; all foreigners were to be killed not in the sudden merciful death of a bullet but sliced to death by big, old rusty knives and swords.... I had an old Winchester rifle and plenty of ammunition ready for the journey....The Boxer uprising ultimately claimed the lives of more than 32,000 Chinese Christians and several hundred foreign missionaries (historian Nat Brandt called it “the greatest single tragedy in the history of Christian evangelicalism”[7] | ” |

- Father Geoffrey Korz, of the Orthodox church, wrote:

| “ | By June 1900, placards calling for the death of foreigners and Christians covered the walls around Beijing. Armed bands combed the streets of the city, setting fire to homes and "with imperial blessing" killing Chinese Christians and foreigners.[8] | ” |

Siege in Peking

The compound in Peking remained under siege from Boxer forces from 20 June to 14 August. Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and security personnel defended the compound with one old muzzle-loaded cannon; it was nicknamed the "International Gun" because the barrel was British, the carriage was Italian, the shells were Russian, and the crew were from the United States.

During the defence of the Legations the Japanese force (if such it could be called, so small was it in number) of 1 officer and 24 sailors, commanded by Colonel Shiba, distinguished itself in several ways. Of particular note was that it had the almost unique distinction of suffering greater than 100% casualties. This was possible because a great many of the Japanese troops were wounded, entered into the casualty lists, then returned to the line of battle only to be wounded once more and again entered in the casualty lists. [9]

Foreign media described the fighting going on in Peking as well as the alleged torture and murder of captured foreigners. Whilst it is true that thousands of Chinese Christians were massacred in north China, many horrible stories that appeared in world newspapers were based on a deliberate fraud [10].

Nonetheless a wave of anti-Chinese sentiment arose in Europe, the United States and Japan. [11]The poorly armed Boxer rebels were unable to break into the compound, which was relieved by an international army of the Eight-Nation Alliance in July.

Boxer rebels, murderers or patriots?

Yuan Weishi is a professor of philosophy at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou, China. In 2006, professor Yuan published an essay titled Modernisation and History Textbooks, criticizing the official theme of government issued middle schools history textbooks, claiming that they contain numbers of non-neutral historical interpretations.

Professor Yuan stated that the Boxers:

(1)cut down telegraph lines

(2)destroyed schools and churches

(3)demolished railroad tracks

(4)burned foreign merchandise

(5)killed foreigners and all Chinese who had any connection of foreign culture.

Prosessor Yuan:"these criminal actions brought unspeakable suffering to the nation and its people! These are all facts that everybody knows, and it is a national shame that the Chinese people cannot forget."[12]

Professor Yuan Weishi stated that Chinese middle schools were using history textbooks with inaccurate and often biased interpretations of history to present "an incomplete history of China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing, that fosters blind nationalism and close-minded anti-foreign sentiment."[13]

For many years, history text books had been lacking in neutrality in presenting the Boxer Rebellion as a "magnificent feat of patriotism", and not presenting the view that the majority of the Boxer rebels both violent and xenophobic.

Professor Yuan stated that Manchu rulers did not comply with signed international treaties, and that it is wrong to blame "the Opium Wars of the mid-1800s entirely on foreign nations".[14]

The torching of Hanlin Yuan,buildings that housed the Yongle Dadian

on 23 June 1900, the Boxer rebels started setting fire to an area of native dwellings south of the British Legation, using it as a 'frightening tactic' to attack the defenders. And Hanlin Yuan, 'a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship . . . the oldest and richest library in the world.'(Yongle Dadian) was just nearby.[15] Sir Claude MacDonald, the commander-in-chief, had become worried that the Boxer rebels might try to burn the Hanlin Yuan, the 'buildings at some point being only an arm's length from the British building walls'.

On 24 June 1900, when the winds shifted, the unanticipated happened:Hanlin Yuan's group of building had caught fire, and the fire was beginning to spread further. Eyewitness' accounts:

| “ | The old buildings burned like tinder with a roar which drowned the steady rattle of musketry as Tung Fu-shiang's Moslems fired wildly through the smoke from upper windows. | ” |

| “ | Some of the incendiaries were shot down, but the buildings were an inferno and the old trees standing round them blazed like torches. | ” |

An eyewitness, Lancelot Giles, son of Herbert A. Giles, described:

| “ | An attempt was made to save the famous Yung Lo Ta Tien, now spelled Yongle Dadian, but heaps of volumes had been destroyed, so the attempt was given up. | ” |

The Manchu authority blamed the British for setting the fire as a defensive measure, whereas the British pointed to the direction of the wind, and confirmed that it was either the Boxer rebels or the regular Manchu soldiers who 'set fire to the Hanlin, working systematically from one courtyard to the next.'[16]

Eight-Nation Alliance

The rebellion was stopped by an alliance of eight nations consisting of Austria-Hungary, French Third Republic, German Empire, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Reinforcements

Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. On 31 May, before the sieges had started and upon the request of foreign embassies in Beijing, an International force of 435 navy troops from eight countries were dispatched by train from Takou to the capital (75 French, 75 Russian, 75 British, 60 U.S., 50 German, 40 Italian, 30 Japanese, 30 Austrian); these troops joined the legations and were able to contribute to their defense.

First intervention (Seymour column)

As the situation worsened, a second International force of 2,000 marines under the command of the British Vice Admiral Edward Seymour, the largest contingent being British, was dispatched from Takou to Beijing on 10 June. The troops were transported by train from Takou to Tianjin with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway between Tianjin and Beijing had been severed. Seymour however resolved to move forward and repair the rail or such as the train, or progress on foot as necessary, keeping in mind that the distance between Tianjin and Beijing was only 120 kilometers.

After Tianjin however, the convoy was surrounded, the railway behind and in front of them was destroyed, and they were attacked from all parts by Chinese irregulars and even Chinese governmental troops. News arrived on 18 June regarding attacks on foreign legations. Seymour decided to continue advancing, this time along the Pei-Ho river, towards Tong-Tcheou, 25 kilometers from Beijing. By the 19th, they had to abandon their efforts due to progressively stiffening resistance, and started to retreat southward along the river with over two hundred wounded. Commandeering four civilian Chinese junks along the river, they loaded all their wounded and remaining supplies onto them and pulled them along with ropes from the riverbanks. By this point, they were very low on food, ammunition and medical supplies. Luckily, they then happened upon The Great Hsi-Ku Arsenal, a hidden Qing munitions cache that the western powers had no knowledge of until then. They immediately captured and occupied it, discovering not only German Krupp made field guns, but rifles with millions of rounds in ammunition, along with millions of pounds of rice. Further, medical supplies were ample too.

There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant was able to infiltrate through the boxer and Qing lines, informing the western powers of their predicament. Surrounded and attacked nearly around the clock by Qing troops and boxers, they were at the point of being overrun. On 25 June however a regiment composed of 1800 men, (900 Russian troops from Port-Arthur, 500 British seamen, with an ad hoc mix of other assorted western troops) finally arrived. Spiking the mounted field guns and setting fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimate £3 million worth), they departed the Hsi-Ku Arsenal in the early morning of 26 June, with the loss of 62 killed and 228 wounded.[17]

Second intervention

| Forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance (1900 Boxer Rebellion) |

|||

| Countries | Warships (units) |

Marines (men) |

Army (men) |

| Japan | 18 | 540 | 20,300 |

| Russia | 10 | 750 | 12,400 |

| United Kingdom | 8 | 2,020 | 10,000 |

| France | 5 | 390 | 3,130 |

| United States | 2 | 295 | 3,125 |

| Germany | 5 | 600 | 300 |

| Italy | 2 | 80 | |

| Austria–Hungary | 1 | 75 | |

| Total | 51 | 4,750 | 49,255 |

With a difficult military situation in Tianjin, and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On 17 June, they took the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore.

The international force, with British Lieutenant-General Alfred Gaselee acting as the commanding officer, called the Eight-Nation Alliance, eventually numbered 54,000, with the main contingent being composed of Japanese soldiers: Japanese (20,840), Russian (13,150), British (12,020), French (3,520), U.S.(3,420), German (900), Italian (80), Austro-Hungarian (75), and anti-Boxer Chinese troops.[18] The international force finally captured Tianjin on 14 July under the command of the Japanese colonel Kuriya, after one day of fighting.

Notable exploits during the campaign were the seizure of the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by Roger Keyes.

The march from Tianjin to Beijing of about 120 km consisted of about 20,000 allied troops. On 4 August there were approximately 70,000 Imperial troops with anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way.They only encountered minor resistance and the battle was engaged in Yangcun, about 30 km outside Tianjin, where the 14th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. and British troops led the assault. However, the weather was a major obstacle, extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 110 °F (43 Celsius).

The International force reached and occupied Beijing on 14 August. The United States was able to play a secondary, but significant role in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion largely due to the presence of U.S. ships and troops deployed in the Philippines since the U.S conquest of the Spanish American and Philippine-American War. In the United States military, the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion was known as the China Relief Expedition.

The end of rebellion

The siege was finally ended when Indian soldiers of the international expeditionary force arrived under the command of German general Alfred Graf von Waldersee; they arrived too late to take part in the main fighting, but undertook several punitive expeditions against the Boxers. Troops from most nations engaged in plunder, looting and rape. German troops in particular were criticized for their enthusiasm in carrying out Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany's 27 July order:

| “ | Make the name German remembered in China for a thousand years so that no Chinaman will ever again dare to even squint at a German.[19] | ” |

The speech, in which Wilhelm invoked the memory of the 5th century Huns, gave rise to the British derogatory name "Hun" for their German enemy during World War I and World War II.

Reparations

On 7 September 1901, the Qing court was compelled to sign the "Boxer Protocol" also known as Peace Agreement between the Eight-Nation Alliance and China. The protocol ordered the execution of ten high-ranking officials linked to the outbreak, and other officials who were found guilty for the slaughter of Westerners in China.

China was fined war reparations of 450,000,000 tael of fine silver (around 67.5 million pounds approximately equal to US$6.653 billion today.[20]) for the loss that it caused. The reparation would be paid within 39 years, and would be 982,238,150 taels with interests (4% per year) included. To help meet the payment, it was agreed to increase the existing tariff from an actual 3.18% to 5%, and to tax hitherto duty-free merchandise. The sum of reparation was estimated by the Chinese population (roughly 450 million in 1900), to let each Chinese pay one tael. Chinese custom income and salt tax were enlisted as guarantee of the reparation. Russia got 30% of the reparation, Germany 20%, France 15.75%, Britain 11.25%, Japan 7.7% and the US share was 7%.[21]

China paid 668,661,220 taels of silver from 1901 to 1939. The British signatory of the Protocol was Sir Ernest Satow.

An excess of the reparations paid to the United States was diverted to pay for the education of Chinese students in U.S. universities under the Boxer Rebellion Indemnity Scholarship Program. To prepare the students chosen for this program an institute was established to teach the English language and to serve as a preparatory school for the course of study chosen. When the first of these students returned to China they undertook the teaching of subsequent students, from this institute was born Tsinghua University. Some of the reparation due to Britain was later earmarked for a similar program.

The China Inland Mission lost more members than any other missionary agency[22]: 58 adults and 21 children were killed. However, in 1901, when the allied nations were demanding compensation from the Chinese government, Hudson Taylor refused to accept payment for loss of property or life in order to demonstrate the meekness of Christ to the Chinese.[23]

Aftermath

The imperial government's humiliating failure to defend China against the foreign powers contributed to the growth of nationalist resentment against the "foreigner" Qing dynasty (who were descendants of the Manchu conquerors of China) and an increasing feeling for modernization, which was to culminate a decade later in the dynasty's overthrow and the establishment of the Republic of China. The foreign privileges which had angered Chinese people were largely cancelled in the 1930s and 1940s.

In October 1900, Russia was busy occupying much of the northeastern province of Manchuria, a move which threatened Anglo-American hopes of maintaining what remained of China's territorial integrity and an openness to commerce under the Open Door Policy. This behavior led ultimately to the Russo-Japanese War, where Russia was defeated at the hands of an increasingly confident Japan.

Results

During the incident, 48 Catholic missionaries and 18,000 Chinese Catholics were murdered. 222 Chinese Eastern Orthodox Christians were also murdered, along with 182 Protestant missionaries and 500 Chinese Protestants known as the China Martyrs of 1900.

The effect on China was a weakening of the dynasty as well as a weakened national defense. The structure was temporarily sustained by the Europeans who were under the impression that the Boxer Rebellion was anti-Qing. Besides the compensation, Empress Dowager Cixi realized that in order to survive, China had to reform despite her previous view of European opposition. Among the Imperial powers, Japan gained prestige due to its military aid in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion and was now seen as a power. Its clash with Russia over the Liaodong and other provinces in eastern Manchuria, long considered by the Japanese as part of their sphere of influence, led to the Russo-Japanese War when two years of negotiations broke down in February 1904. Germany earned itself the nickname "Hun" and occupied Qingdao bay, consequently fortifying it to serve as Germany's primary naval base in East Asia. The Russian Lease of the Liaodong (1898) was confirmed.

The U.S. 9th Infantry Regiment earned the nickname "Manchus" for its actions during this campaign and members of the regiment (stationed in Camp Casey, South Korea) still do a commemorative 25 mile (40 km) foot march every quarter in remembrance of the brutal fighting. Soldiers who complete this march are authorized to wear a special belt buckle that features a Chinese imperial dragon on their uniforms. Likewise both the U.S. 14th Infantry Regiment, which calls itself "The Golden Dragons"; the 15th Infantry Regiment; the U.S. 6th Cavalry Regiment; the US 3rd Artillery (see Coats of arms of U.S. Field Artillery Regiments) also have a Golden Dragon on their coat of arms. Another U.S. unit involved in the rebellion was the first formation of "2d Regiment" of USMC detachments.

The impact on China was immense. Soon after the rebellion the Imperial examination system for government service was eliminated; as a result, the classical system of education was replaced with a Westernized system that led to a university degree. Eventually the spirit of revolution sparked a new nationalist revolution, ironically led by a Christian Sun Yat-sen, which overthrew the Manchu (Qing) Dynasty.

Fictional interpretations

- The 1963 film 55 Days at Peking was a dramatization of the Boxer rebellion. Shot in Spain, it needed thousands of extras, and the company sent scouts throughout Spain to hire as many as they could find. [24]

- In 1975, Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers studio produced the film Boxer Rebellion(八國聯軍, Pa kuo lien chun) under director Chang Cheh with one of the highest budget to tell a sweeping story of disillusionment and revenge[25]. It depicted followers of the Boxer clan being duped into believing they were impervious to attacks by firearms. The film starred Alexander Fu Sheng, Chi Kuan Chun and Wang Lung-Wei.

- The novel Moment In Peking by Lin Yutang, opens during the Boxer Rebellion, and provides a child's-eye view of the turmoil through the eyes of the protagonist.

- The novel The Palace of Heavenly Pleasure, by Adam Williams, describes the experiences of a small group of western missionaries, traders and railway engineers in a fictional town in Northern China shortly before and during the Boxer Rebellion.

- Parts I and II of C. Y. Lee's China Saga (1987) involve events leading up to and during the Boxer Rebellion, revolving around a character named Fong Tai.

- The horror play La Dernière torture (The Ultimate Torture), written by André de Lorde and Eugène Morel in 1904 for the Grand Guignol theater (just four years following the events depicted), is set during the Boxer Rebellion, in the French area of the fortified legation compound, specifically on 22 July 1900, the thirty-second day of the Boxers' siege of the compound.

- The Last Empress (novel), by Anchee Min, describes the long reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi in which the siege of the legations is one of the climax in the novel.

- For More Than Glory by William C. Dietz claims to be a science fictionalized novel loosely based on the events of the boxer rebellion

Footnotes

- ↑ Esherick, 154

- ↑ Spence, In Search of Modern China, pp. 230-235; Keith Schoppa, Revolution and Its Past, pp. 118-123.

- ↑ Esherick p. xiv. Esherick notes that many textbooks and secondary accounts followed Victor Purcell, The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study (1963) in seeing a shift from anti-dynastic to pro-dynastic, but that the “flood of publications” from Taiwan and the People’s Republic (including both documents from the time and oral histories conducted in the 1950s) has shown this not to be the case. xv-xvi

- ↑ "Imperialism, for Christ's Sake," Ch. 3 , Esherick, The Origins of the Boxer Uprising, pp. 68-95.

- ↑ "The Gathering Storm," Ch 7, "Prairie Fire," Ch 10 Esherick, pp. 167-205, 271-313.

- ↑ "The Boxer Rebellion", bms world mission. Retrieved on 2008-10-14.

- ↑ "Lost in the Gobi Desert Hart retraces great-grandfather’s footsteps", University Relation (1 March 2005). Retrieved on 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "The Chinese Martyrs of the Boxer Rebellion Contributed by Fathe", All Saints of North America Orthodox church. Retrieved on 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Fleming, 1959. PP 143-144.

- ↑ Preston (2000) Page 173-4.

- ↑ Elliott (1996)

- ↑ "History Textbooks in China", Eastsouthwestnorth. Retrieved on 2008-10-23.

- ↑ Pan, Philip P. (2006-01-25). "Leading Publication Shut Down In China", The Washington Post, The Washington Post Company. Retrieved on 2008-10-22.

- ↑ "Leading Publication Shut Down In China", Washington Post Foreign Service (25 January 2006). Retrieved on 2008-10-19.

- ↑ "Destruction Of Chinese Books In The Peking Siege Of 1900 Donald G. Davis, Jr. University of Texas at Austin, USA Cheng Huanwen Zhongshan University, PRC", International Federation of Library Association. Retrieved on 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "BOXER REBELLION // CHINA 1900", HISTORIK ORDERS, LTD WEBSITE. Retrieved on 2008-10-20.

- ↑ Account of the Seymour column in "The Boxer Rebellion", pgs 100-104, Diane Preston

- ↑ Russojapanesewarweb

- ↑ Eugene, Melvin. Sonnenburg, Penny M. [2003] (2003). Digitized 2006. Colonialism: An International, Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ISBN 1576073351

- ↑ http://eh.net/atp/answers/0789.php

- ↑ Hsu, 481

- ↑ http://www.archive.org/details/martyredmission02broogoog

- ↑ Broomhall (1901), several pages

- ↑ 55 Days at Peking at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ HKflix

References

- Brandt, Nat (1994). Massacre in Shansi. Syracuse U. Press. ISBN 0815602820, ISBN 1583483470 (Pbk).

- Broomhall, Marshall (1901). Martyred Missionaries of The China Inland Mission; With a Record of The Perils and Sufferings of Some Who Escaped. London: Morgan and Scott. http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC01471430&id=yVtXfdulqUMC&pg=PR3&dq=broomhall+martyred.

- Chen, Shiwei. "Change and Mobility: the Political Mobilization of the Shanghai Elites in 1900." Papers on Chinese History 1994 3(spr): 95-115.

- Cohen, Paul A. (1997). History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth Columbia University Press. online edition

- Cohen, Paul A. "The Contested Past: the Boxers as History and Myth." Journal of Asian Studies 1992 51(1): 82-113. Issn: 0021-9118

- Elliott, Jane. "Who Seeks the Truth Should Be of No Country: British and American Journalists Report the Boxer Rebellion, June 1900." American Journalism 1996 13(3): 255-285. Issn: 0882-1127

- Esherick, Joseph W. (1987). The Origins of the Boxer Uprising University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06459-3

- Harrison, Henrietta. "Justice on Behalf of Heaven." History Today (2000) 50(9): 44-51. Issn: 0018-2753.

- Jellicoe, George (1993). The Boxer Rebellion, The Fifth Wellington Lecture, University of Southampton, University of Southampton. ISBN 0854325166.

- Hsu, Immanuel C.Y. (1999). The rise of modern China, 6 ed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195125045.

- Hunt, Michael H. "The Forgotten Occupation: Peking, 1900–1901." Pacific Historical Review 48 (4) (Nov. 1979): 501–529.

- Preston, Diana (2000). The Boxer Rebellion. Berkley Books, New York. ISBN 0-425-18084-0. online edition

- Preston, Diana. "The Boxer Rising." Asian Affairs (2000) 31(1): 26-36. ISSN 0306-8374.

- Purcell, Victor (1963). The Boxer Uprising: A background study. online edition

- Seagrave, Sterling (1992). Dragon Lady: The Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China Vintage Books, New York. ISBN 0-679-73369-8. Challenges the notion that the Empress-Dowager used the Boxers. She is portrayed sympathetically.

- Tiedemann, R. G. "Boxers, Christians and the Culture of Violence in North China." Journal of Peasant Studies 1998 25(4): 150-160. ISSN 0306-6150.

- Warner, Marina (1993). The Dragon Empress The Life and Times of Tz'u-hsi, 1835-1908, Empress Dowager of China. Vintage. ISBN 0-09-916591-0

- Eva Jane Price. China journal, 1889-1900: an American missionary family during the Boxer Rebellion, (1989). ISBN 0-684-19851-8; see Susanna Ashton, "Compound Walls: Eva Jane Price's Letters from a Chinese Mission, 1890-1900." Frontiers 1996 17(3): 80-94. ISSN: 0160-9009.

- Fleming, P. (1959) The Seige at Peking, Rupert Hart Davis, ISBN 1 84158 098 8

External links

- 55 Days at Peking at the Internet Movie Database

- Pa kuo lien chun at the Internet Movie Database

- U. of Washington Library's Digital Collections – Robert Henry Chandless Photographs

|

|||||||||||