Bosnian War

| Bosnian War/War in Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Yugoslav Wars | ||||||||

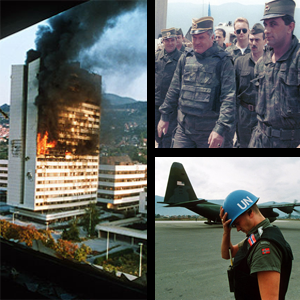

The parliament building burns after being hit by artillery fire in Sarajevo May 1992.; Ratko Mladić with Bosnian Serb soldiers; a Norwegian UN soldier in Sarajevo. Photos by Mikhail Evstafiev |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

NATO (Operation Deliberate Force, 1995) |

||||||||

| Commanders | ||||||||

(President of Bosnia and Herzegovina) (ARBiH Chief of Staff 1992-1993) (ARBiH Chief of Staff 1993-1995) |

(President of Croatia) (President of CR Herzeg-Bosnia) (HVO Chief of Staff) (political leader of Croats in Central Bosnia) |

(President of Serbia) (President of Republika Srpska) (Chief of Staff, VRS) |

||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

| ~100 tanks ~200,000 infantry |

~300 tanks ~70,000 infantry |

600-700 tanks 120,000 infantry |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| 31,270 soldiers killed 32,723 civilians killed |

5,439 soldiers killed 1,899 civilians killed |

20,649 soldiers killed 3,555 civilians killed |

||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

The War in Bosnia and Herzegovina, commonly known as the Bosnian War, was an international armed conflict that took place between March 1992 and November 1995. The war involved several sides. According to numerous International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia judgements the conflict involved Bosnia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (later Serbia and Montenegro) [1] as well as Croatia.[2] According to an International Court of Justice judgment, Serbia gave military and financial support to Serb forces which consisted of the Yugoslav People's Army, the Army of Republika Srpska, the Serbian Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of the Interior of Republika Srpska and Serb Territorial Defense Forces. Croatia gave military support to Croat forces of self-proclaimed Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia. Bosnian government forces were led by the Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[3] These factions changed objectives and allegiances several times at various stages of the war.

Because the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina was a consequence of the instability in the wider region of the former Yugoslavia, and due to the involvement of neighboring countries Croatia and Serbia and Montenegro, there was long-standing debate as to whether the conflict was a civil war or a war of aggression. Most Bosniaks and many Croats, western politicians and human rights organisations claimed that the war was a war of Serbian and Croatian aggression based on the Karađorđevo agreement, while Serbs often considered it a civil war. A trial took place before the International Court of Justice, following a 1993 suit by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia and Montenegro alleging genocide (see Bosnian genocide case at the International Court of Justice). The International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling of 26 February 2007 indirectly determined the war's nature to be international, though clearing Serbia of direct responsibility for the genocide committed by the forces of Republika Srpska. The ICJ concluded, however, that Serbia failed to prevent genocide committed by Serb forces and failed to punish those who carried out the genocide, especially General Ratko Mladić, and bring them to justice.

Despite the evidence of widespread killings, the siege of towns, mass rape, ethnic cleansing and torture in concentration camps and detention centers conducted by different Serb forces including JNA (VJ), especially in Prijedor, Zvornik, Banja Luka and Foča, the judges ruled that the criteria for genocide with the specific intent (dolus specialis) to destroy Bosnian Muslims were met only in Srebrenica or Eastern Bosnia in 1995.[4] The court concluded that the crimes committed during the 1992-1995 war, may amount to crimes against humanity according to the international law, but that these acts did not, in themselves, constitute genocide per se.[5] The Court further decided that, following Montenegro's declaration of independence in May 2006, Serbia was the only respondent party in the case, but that "any responsibility for past events involved at the relevant time the composite State of Serbia and Montenegro".[6]

The involvement of NATO, during the 1995 Operation Deliberate Force against the positions of the Army of Republika Srpska internationalized the conflict, but only in its final stages.

The war was brought to an end after the signing of the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina in Paris on 14 December 1995.[7] Peace negotiations were held in Dayton, Ohio, and were finalized on 21 December 1995. The accords are known as the Dayton Agreement.

The most recent research places the number of victims at around 100,000–110,000 killed (civilians and military), and 1.8 million displaced (see Casualties).[8][9][10] Recent research has shown that most of the 97,207[11] documented casualties (soldiers and civilians) during Bosnian War were Bosniaks (66%), with Serbs in second (25%) and Croats (8%) in third place.[12] However, 83 percent of civilian victims were Bosniaks, 10 percent were Serbs and more than 5 percent were Croats, followed by a small number of others such as Albanians or Romani people. Some 30 per cent [at least] of the Bosniak civilian victims were women and children[13]. The percentage of Bosniak civilian victims would be higher had survivors of Srebrenica not reported 1,800 of their loved-ones as soldiers to access social services and other government benefits. The total figure of dead could rise by a maximum of another 10,000 for the entire country due to ongoing research. [14] [15] [16] [15][17]

According to a detailed 1995 report about the war made by the Central Intelligence Agency, 90% of the war crimes of the Bosnian War were committed by Serbs.[18] According to legal experts, as of early 2008, 45 Serbs, 12 Croats and 4 Bosniaks were convicted of war crimes by the ICTY in connection with the Balkan wars of the 1990s.[19] Both Serbs and Croats were indicted and convicted of organized crimes (joint criminal enterprise), while Bosniaks of individual ones. Some high ranking political leaders of Serbs (Momčilo Krajišnik and Biljana Plavšić) as well as Croats (Dario Kordić) were convicted of war crimes, while some others are presently on trials at the ICTY (Radovan Karadžić and Jadranko Prlić). Genocide is the most serious war crime the Serbs were convicted of, crimes against humanity, a charge second in gravity only to genocide (i.e. ethnic cleansing) for the Croats, and breaches of the Geneva Conventions for the Bosniaks (Mucic et al.).[20]

Contents |

Breakup of Yugoslavia

The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina came about as a result of the breakup of Yugoslavia. In 1989 Slobodan Milošević became President of Serbia (later indicted by the ICTY of the war crimes including genocide in Bosnia, Croatia and Kosovo). Crisis emerged in Yugoslavia with the weakening of the Communist system at the end of the Cold War. In Yugoslavia, the national Communist party, officially called Alliance or League of Communists of Yugoslavia, was losing its ideological potency, while the nationalist and separatist ideologies were on the rise in the late 1980s. This was particularly noticeable in Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to a lesser extent in Slovenia and Republic of Macedonia.

In March 1989, the crisis in Yugoslavia deepened after adoption of amendments to the Serbian constitution which allowed the Serbian republic's government to impose effective power over the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. Until that point, their decision-making had been independent. Each also had a vote on the Yugoslav federal level. Serbia, under president Slobodan Milošević, thus gained control over three out of eight votes in the Yugoslav presidency. With additional votes from Montenegro, Serbia was thus able to heavily influence decisions of the federal government. This situation led to objections in other republics and calls for reform of the Yugoslav Federation.

At the 14th Extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, on 20 January 1990, the delegations of the republics could not agree on the main issues in the Yugoslav federation. As a result, the Slovenian and Croatian delegates left the Congress. The Slovenian delegation, headed by Milan Kučan demanded democratic changes and a looser federation, while the Serbian delegation, headed by Milošević, opposed this. This is considered the beginning of the end of Yugoslavia.

Moreover, nationalist parties attained power in other republics. Among them, the Croatian Franjo Tuđman's Croatian Democratic Union was the most prominent. On December 22, 1990, the Parliament of Croatia adopted the new Constitution, taking away some of the rights from the Serbs granted by the previous Socialist constitution. This created ground for nationalist action among the indigenous Serbs of Croatia. Furthermore, Slovenia and Croatia shortly after began the process towards independence, which led to a short armed conflict in Slovenia, and all-out war in Croatia, in the areas that had a substantial Serb population.

Karađorđevo agreement

Secret discussions between Franjo Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević on the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia were held as early as March 1991 known as Karađorđevo agreement. Following the declaration of independence of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Serbs attacked different parts of the country. The state administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina effectively ceased to function having lost control over the entire territory. The Serbs wanted all lands where Serbs had a majority, eastern and western Bosnia. The Croats and their leader Franjo Tuđman also aimed at securing parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina as Croatian. The policies of the Republic of Croatia and its leader Franjo Tuđman towards Bosnia and Herzegovina were never totally transparent and always included Franjo Tuđman's ultimate aim of expanding Croatia's borders. Bosnian Muslims, the only ethnic group loyal to the Bosnian government, were an easy target, because the Bosnian government forces were poorly equipped and unprepared for the war.[21]

The pre-war situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina has historically been a multi-ethnic state. In 1990, its population included approximately 43% of Bosniaks, 31% of Serbs, and 17% of Croats.

On the first multi-party elections that took place in November 1990 in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the three largest ethnic parties in the country won: the Bosniak Party of Democratic Action, the Serbian Democratic Party and the Croatian Democratic Union.

.

Parties divided the power along the ethnic lines so that the President of the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was a Bosniak, president of the Parliament was a Serb and the prime minister a Croat.

Establishment of the "Serb Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina"

The Serb members of parliament, consisting mainly of the Serb Democratic Party members, but also including some other party representatives (which would form the "Independent Members of Parliament Caucus"), abandoned the central parliament in Sarajevo, and formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina on October 24, 1991, which marked the end of the tri-ethnic coalition that governed after the elections in 1990. This Assembly established the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on January 9, 1992, which became Republika Srpska in August 1992. The official aim of this act, stated in the original text of the Constitution of Republika Srpska, later amended, was to preserve the Yugoslav federation.

Establishment of the "Croat Community of Herzeg-Bosnia"

The objectives of nationalists from Croatia were shared by Croat nationalists in Bosnia and Herzegovina. [22] The ruling party in the Republic of Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), organized and controlled the branch of the party in Bosnia and Herzegovina. By the latter part of 1991, the more extreme elements of the party, under the leadership of Mate Boban, Dario Kordić, Jadranko Prlić, Ignac Koštroman and local leaders such as Anto Valenta[22], and with the support of Franjo Tuđman and Gojko Šušak, had taken effective control of the party. On November 18, 1991, the party branch in Bosnia and Herzegovina, proclaimed the existence of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia, as a separate "political, cultural, economic and territorial whole", on the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina. [23]

Independence referendum in Bosnia and Herzegovina

After Slovenia and Croatia declared independence from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1991, Bosnia and Herzegovina organized a referendum on independence as well. The decision of the Parliament of Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina on holding the referendum was taken after the majority of Serb members had left the assembly in protest.

These Bosnian Serb assembly members invited the Serb population to boycott the referendums held on February 29 and March 1, 1992. The turnout to the referendums was 67% and the vote was 99.43% in favor of independence. [24] Independence was declared on March 5, 1992 by the parliament. The referendums were utilized by the Serb political leadership as a reason to start road blockades in protest.

Cutileiro-Carrington Plan

The Lisbon Agreement, also known as the Carrington-Cutileiro plan, named for its creators Lord Peter Carrington and Portuguese Ambassador José Cutileiro, resulted from the EEC-hosted conference held in September 1991 in an attempt to prevent Bosnia and Herzegovina sliding into war. It proposed ethnic power-sharing on all administrative levels and the devolution of central government to local ethnic communities. However, all Bosnia and Herzegovina's districts would be classified as Bosniak, Serb or Croat under the plan, even where ethnic majority was not evident.

On March 18, 1992, all three sides signed the agreement; Alija Izetbegović for the Bosniaks, Radovan Karadžić for the Serbs and Mate Boban for the Croats.

However, on March, 28 1992, Izetbegović, after meeting with then US ambassador to Yugoslavia Warren Zimmermann in Sarajevo, withdrew his signature and declared his opposition to any type of ethnic division of Bosnia.

- What was said and by whom remains unclear. Zimmerman denies that he told Izetbegovic that if he withdrew his signature, the United States would grant recognition to Bosnia as an independent state. What is indisputable is that Izetbegovic, that same day, withdrew his signature and renounced the agreement.[25]

Arms embargo

On September 25, 1991 the United Nations Security Council passed UNSC Resolution 713 imposing an arms embargo on all of former Yugoslavia. The embargo hurt the Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina the most because Serbia inherited the lion's share of the former JNA arsenal and the Croatian army could smuggle weapons through its coast. Over 55% of the armories and barracks of the former Yugoslavia were located in Bosnia owing to its mountainous terrain, in anticipation of a guerrilla war, but many of those factories were under Serbian control (such as the UNIS PRETIS factory in Vogošća), and others were inoperable due to a lack of electricity and raw materials. The Bosnian government lobbied to have the embargo lifted but that was opposed by the United Kingdom, France and Russia. US proposals to pursue this policy were known as lift and strike. The US congress passed two resolutions calling for the embargo to be lifted but both were vetoed by President Bill Clinton for fear of creating a rift between the US and the aforementioned countries. Nonetheless, the United States used both "black" C-130 transports and back channels including Islamist groups to smuggle weapons to the Bosnian government forces via Croatia. [26]

War

Background

The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) officially left Bosnia and Herzegovina on May 12, 1992 shortly after independence was declared in April 1992. However, most of the command chain, weaponry, and higher ranked military personnel, including general Ratko Mladić, remained in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Army of Republika Srpska. The Croats organized a defensive military formation of their own called the Croatian Defense Council (Hrvatsko Vijeće Obrane, HVO) as the armed forces of the self-proclaimed Herzeg-Bosnia. The Bosniaks mostly organized into the Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Armija Republike Bosne i Hercegovine, Armija RBiH). This army had a number of non-Bosniaks (around 25%), especially in the 1st Corps in Sarajevo. The deputy commander of the Bosnian Army's Headquarters, was general Jovan Divjak, the highest ranking ethnic Serb in the Bosnian Army. General Stjepan Šiber, an ethnic Croat was the second deputy commander. President Izetbegović also appointed colonel Blaž Kraljević, commander of the Croatian Defence Forces in Herzegovina, to be a member of Bosnian Army's Headquarters, seven days before his assassination, in order to assemble multi-ethnic pro-Bosnian defence front.[27]

Various paramilitary units were operating in Bosnian war: the Serb "White Eagles" (Beli Orlovi), Arkan's "Tigers", "Serbian Volunteer Guard" (Srpska Dobrovoljačka Garda), Bosniak "Patriotic League" (Patriotska Liga) and "Green Berets" (Zelene Beretke), and Croatian "Croatian Defense Forces" (Hrvatske Obrambene Snage), etc. The Serb and Croat paramilitaries involved volunteers from Serbia and Croatia, and were supported by nationalist political parties in those countries. Allegations exist about the involvement of the Serbian and Croatian secret police in the conflict. Forces of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina were divided in 5 corps'. 1st Corps operated at the region of Sarajevo and Gorazde while a stronger 5th Corps was positioned in the western Bosanska Krajina pocket which cooperated with the HVO units in and around the city of Bihac.

The Serbs received support from Christian Slavic fighters from countries including Russia. Greek volunteers are also reported to have taken part in the Srebrenica Massacre, with the Greek flag being hoisted in Srebrenica when the town fell to the Serbs.[28]

Some radical Western fighters as well as numerous individuals from the cultural area of Western Christianity fought as volunteers for the Croats including Neo-Nazi volunteers from Germany and Austria. Swedish Neo-Nazi Jackie Arklöv was charged with war crimes upon his return to Sweden. Later he confessed he committed war crimes on Bosniak civilians in Croatian camps Heliodrom and Dretelj as a member of Croatian forces.[29]

The Bosniaks received support from Islamic groups commonly known as "holy warriors" (Mujahideen). There were also several hundred Iranian Revolutionary Guards assisting the Bosnian government during the war.[30]

At the outset of the Bosnian war, Serb forces attacked the Bosnian Muslim civilian population in eastern Bosnia. Once towns and villages were securely in their hands, the Serb forces - military, police, the paramilitaries and, sometimes, even Serb villagers – applied the same pattern: houses and apartments were systematically ransacked or burnt down, civilians were rounded up or captured, and sometimes beaten or killed in the process. Men and women were separated, with many of the men detained in the camps. The women were kept in various detention centres where they had to live in intolerably unhygienic conditions, where they were mistreated in many ways including being raped repeatedly. Serb soldiers or policemen would come to these detention centres, select one or more women, take them out and rape them.[31] The Serbs had the upper hand due to heavier weaponry (despite less manpower) that was given to them by the Yugoslav People's Army and established control over most areas where Serbs had relative majority but also in areas where they were a significant minority in both rural and urban regions excluding the larger towns of Sarajevo and Mostar. The Serb military and political leaders, from ICTY received the most accusations of war crimes many of which have been confirmed after the war in ICTY trials.

Most of the capital Sarajevo was predominantly held by the Bosniaks although the official Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina government continued to function in its relative multiethnic capacity. In the 44 months of the siege, the terror against Sarajevo and its residents varied in its intensity, but the purpose remained the same: to inflict the greatest possible suffering on the civilians in order to force the Bosnian authorities to accept the Serb demands.[32] The Army of Republika Srpska surrounded it (alternatively, the Serb forces situated themselves in the areas surrounding Sarajevo the so-called Ring around Sarajevo), deploying troops and artillery in the surrounding hills in what would become the longest siege in the history of modern warfare lasting nearly 4 years. See Siege of Sarajevo.

Numerous cease-fire agreements were signed, and breached again when one of the sides felt it was to their advantage. The United Nations repeatedly, but unsuccessfully attempted to stop the war and the much-touted Vance-Owen Peace Plan made little impact.

Chronology

1992

The first casualty in Bosnia is a point of contention between Serbs and Bosniaks. Serbs consider Nikola Gardović, a groom's father who was killed at a Serb wedding procession on the second day of the referendum, on March 1, 1992 in Sarajevo's old town Baščaršija, to be the first victim of the war. Bosniaks and Croats meanwhile consider the first casualties of the war before the independence to be Croat civilians massacred by the Yugoslav People's Army (later transformed in Army of Republika Srpska and Army of Serbia and Montenegro) in Ravno village located in Herzegovina on September 30, 1991 during the JNA attack on Dubrovnik. Bosniaks also consider the first individual casualty of the war after the independence declaration to be Suada Dilberović, who was shot during a peace march by unidentified gunmen on April 5 from a Serb sniper nest in a Holiday Inn hotel.

On September 19, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) moved some extra troops to the area around the city of Mostar, which was publicly protested by the local government. On October 13, 1991 future president of Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić expressed his view about future of Bosnia and Bosnian Muslims: "In just a couple of days, Sarajevo will be gone and there will be five hundred thousand dead, in one month Muslims will be annihilated in Bosnia and Herzegovina". [33]

At the session on January 7, 1992, two days prior to the proclamation of the Republic of Serbian People of B&H, the Serb members of the Prijedor Municipal Assembly and the presidents of the local Municipal Boards of the SDS implemented Instructions for the Organisation and Activity of Organs of the Serbian People in Bosnia and Herzegovina in Extraordinary Circumstances adopted earlier on December 19, 1991 and proclaimed the Assembly of the Serbian People of the Municipality of Prijedor. Milomir Stakić, later convicted by ICTY of mass crimes against humanity against Bosniak and Croat civilians, was elected President of this Assembly. Ten days later, on January 17, 1992, the Assembly endorsed joining the Serbian territories of the Municipality of Prijedor to the Autonomous Region of Bosnian Krajina in order to implement creation of a separate Serbian state on ethnic Serbian territories.[34]

During the months of March-April-May 1992 fierce attacks raged in eastern Bosnia as well as the northwestern part of the country. In March attacks by the SDS leaders, together with field officers of the Second Military Command of former JNA, were conducted in eastern part of the country with the objective to take strategically relevant positions and carry out a communication and information blockade. Attacks carried out resulted in a large number of dead and wounded civilians.[35]

1992 ethnic cleansing campaign in Eastern Bosnia

Initially, the Serb forces attacked the non-Serb civilian population in Eastern Bosnia. Once towns and villages were securely in their hands, the Serb forces - military, police, the paramilitaries and, sometimes, even Serb villagers – applied the same pattern: Bosniak houses and apartments were systematically ransacked or burnt down, Bosniak civilians were rounded up or captured, and sometimes beaten or killed in the process. Men and women were separated, with many of the men detained in the camps.[31]

Bosnian Muslim women were specifically targeted as the rapes against the Bosniak women were one of the many ways in which the Serbs could assert their superiority and victory over the Bosniaks. [31] Women were kept in various detention centres known as rape camps where they had to live in intolerably unhygienic conditions and were mistreated in many ways including being repeatedly raped. Serb soldiers or policemen would come to these detention centres, select one or more women, take them out and rape them. All this was done in full view, in complete knowledge and sometimes with the direct involvement of the Serb local authorities, particularly the police forces. The head of Foča police forces, Dragan Gagović, was personally identified as one of the men who came to these detention centres to take women out and rape them. There were numerous rape camps in Foča. Karaman's house was one of the most notable rape camps. While kept in this house, the girls were constantly raped. Among the women held in "Karaman's house" there were minors as young as 15 years of age. [31][36] So far, there are no exact figures on how many women and children were systematically raped by the Serb forces in various camps[37][38], but estimates range from 20,000[39] to 50,000.[40]

Prijedor region

On April 23, 1992, the SDS decided inter alia that all Serb units immediately start working on the takeover of the Prijedor municipality in co-ordination with JNA. By the end of April 1992, a number of clandestine Serb police stations were created in the municipality and more than 1,500 armed Serbs were ready to take part in the takeover.[34]

A declaration on the takeover prepared by the Serb politicians from SDS was read out on Radio Prijedor the day after the takeover and was repeated throughout the day. In the night of the April 29/30, 1992, the takeover of power took place. Employees of the public security station and reserve police gathered in Cirkin Polje, part of the town of Prijedor. Only Serbs were present and some of them were wearing military uniforms. The people there were given the task of taking over power in the municipality and were broadly divided into five groups. Each group of about twenty had a leader and each was ordered to gain control of certain buildings. One group was responsible for the Assembly building, one for the main police building, one for the courts, one for the bank and the last for the post-office.[41]

Serb authorities set up concentration camps and determined who should be responsible for the running of those camps. [42] Keraterm factory was set up as a camp on or around May 23/24, 1992. [43] The Omarska mines complex was located about 20km from the town of Prijedor. The first detainees were taken to the camp sometime in late May 1992 (between 26 and 30 May). According to the Serb authorities documents from Prijedor, there were a total of 3,334 persons held in the camp from May 27 to August 16, 1992. 3,197 of them were Bosniaks (i.e. Bosnian Muslims), 125 were Croats.[44] The Trnoplje camp was set up in the village of Trnoplje on May 24, 1992. The camp was guarded on all sides by the Serb army. There were machine-gun nests and well-armed posts pointing their guns towards the camp. There were several thousand people detained in the camp, the vast majority of whom were Bosnian Muslim and some of them were Croats. [45][46]

ICTY concluded that the takeover by the Serb politicians was as an illegal coup d'état, which was planned and coordinated a long time in advance with the ultimate aim of creating a pure Serbian municipality. These plans were never hidden and they were implemented in a coordinated action by the Serb police, army and politicians. One of the leading figures was Milomir Stakić, who came to play the dominant role in the political life of the Municipality. [41]

JNA under control of Serbia was able to take over at least 60% of the country during before 19 May official withdrawn all officers and troops which are not from Bosnia [47]. Much of this is due to the fact that they were much better armed and organized than the Bosniak and Bosnian Croat forces. Attacks also included areas of mixed ethnic composition. Doboj, Foča, Rogatica, Vlasenica, Bratunac, Zvornik, Prijedor, Sanski Most, Kljuc, Brčko, Derventa, Modrica, Bosanska Krupa, Bosanski Brod, Bosanski Novi, Glamoc, Bosanski Petrovac, Cajnice, Bijeljina, Višegrad, and parts of Sarajevo are all areas where Serbs established control and expelled Bosniaks and Croats. Also areas in which were more ethnically homogeneous and were spared from major fighting such as Banja Luka, Bosanska Dubica, Bosanska Gradiska, Bileca, Gacko, Han Pijesak, Kalinovik, Nevesinje, Trebinje, Rudo saw their non-Serb populations expelled. Similarly, the regions of central Bosnia and Herzegovina (Sarajevo, Zenica, Maglaj, Zavidovici, Bugojno, Mostar, Konjic, etc.) saw the flight of its Serb population, migrating to the Serb-held areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In June 1992, the United Nations Protection Force which had originally been deployed in Croatia had its mandate extended into Bosnia and Herzegovina, initially to protect the Sarajevo International Airport. In September, the role of the UNPROFOR was expanded in order to protect humanitarian aid and assist in the delivery of the relief in the whole Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as aid in the protection of civilian refugees when required by the Red Cross.

The Croat Defence Council take-overs in Central Bosnia

In June 1992 the focus switched to Novi Travnik and Gornji Vakuf where the Croat Defence Council (HVO) efforts to gain control were resisted. On June 18, 1992 the Bosnian Territorial Defence in Novi Travnik received an ultimatum from the HVO which included demands to abolish existing Bosnia and Herzegovina institutions, establish the authority of the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia and pledge allegiance to it, subordinate the Territorial Defense to the HVO and expel Muslim refugees, all within 24 hours. The attack was launched on June 19. The elementary school and the Post Office were attacked and damaged.[48] Gornji Vakuf was initially attacked by Croats on June 20, 1992, but the attack failed. The Graz agreement caused deep division inside the Croat community and strengthened the separation group, which led to the conflict with Bosniaks. One of the primary pro-union Croat leaders, Blaž Kraljević (leader of the HOS armed group) was killed by HVO soldiers in August 1992, which severely weakened the moderate group who hoped to keep the Bosnian Croat alliance alive[49]. The situation became more serious in October 1992 when Croat forces attacked Bosniak civilian population in Prozor burning their homes and killing civilians. According to Jadranko Prlić indictment, HVO forces cleansed most of the Muslims from the town of Prozor and several surrounding villages.[23]

In October 1992 the Serbs captured the town of Jajce and expelled the Croat and Bosniak population. The fall of the town was largely due to a lack of Bosniak-Croat cooperation and rising tensions, especially over the previous four months.

1993

Serb - red

Croat - blue

Bosniak - green

Split control - white

On January 8, 1993 the Serbs killed the deputy prime minister of Bosnia Hakija Turajlić after stopping the UN convoy which was taking him from the airport. On May 15-16 96% of Serbs voted to reject the Vance-Owen plan. After the failure of the Vance-Owen peace plan, which practically intended to divide the country into three ethnic parts, an armed conflict sprung between Bosniaks and Croats over the 30 percent of Bosnia they held. The peace plan was one of the factors leading to the escalation of the conflict, as Lord Owen avoided moderate Croat authorities (pro-unified Bosnia) and negotiated directly with more extreme elements (which were for separation).[50]

Much of 1993 was dominated by the Croat-Bosniak war. On January 1993 Croat forces attacked Gornji Vakuf again in order to connect Herzegovina with Central Bosnia.[23]

Gornji Vakuf shelling

Gornji Vakuf is a town to the south of the Lašva Valley and of strategic importance at a crossroads en route to Central Bosnia. It is 48 kilometres from Novi Travnik and about one hour's drive from Vitez in an armoured vehicle. For Croats it was a very important connection between the Lašva Valley and Herzegovina, two territories included in the self-proclaimed Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia. The Croat forces shelling reduced much of the historical oriental center of the town of Gornji Vakuf to rubble. [51]

On January 10, 1993, just before the outbreak of hostilities in Gornji Vakuf, the Croat Defence Council (HVO) commander Luka Šekerija, sent a "Military – Top Secret" request to Colonel Tihomir Blaškić and Dario Kordić, (later convicted by ICTY of war crimes and crimes against humanity i.e. ethnic cleansing) for rounds of mortar shells available at the ammunition factory in Vitez. [52] Fighting then broke out in Gornji Vakuf on January 11, 1993, sparked by a bomb which had been placed by Croats in a Bosniak-owned hotel that had been used as a military headquarters. A general outbreak of fighting followed and there was heavy shelling of the town that night by Croat artillery. [51]

During cease-fire negotiations at the Britbat HQ in Gornji Vakuf, colonel Andrić, representing the HVO, demanded that the Bosnian forces lay down their arms and accept HVO control of the town, threatening that if they did not agree he would flatten Gornji Vakuf to the ground. [51] [53] The HVO demands were not accepted by the Bosnian Army and the attack continued, followed by massacres on Bosnian Muslim civilians in the neighbouring villages of Bistrica, Uzričje, Duša, Ždrimci and Hrasnica.[54] [55] During the Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing it was surrounded by Croatian Army and Croatian Defence Council for seven months and attacked with heavy artillery and other weapons (tanks and snipers). Although Croats often cited it as a major reason for the attack on Gornji Vakuf, the commander of the British Britbat company claimed that there were no Muslim holy warriors in Gornji Vakuf (commonly known as Mujahideen) and that his soldiers did not see any. The shelling campaign and the attackes during the war resulted in hundreds of injured and killed, mostly Bosnian Muslim civilians. [51]

Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing

The Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing campaign against Bosniak civilians planned by the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia's political and military leadership from May 1992 to March 1993 and erupting the following April, was meant to implement objectives set forth by Croat nationalists in November 1991.[22] The Lašva Valley's Bosniaks were subjected to persecution on political, racial and religious grounds[56], deliberately discriminated against in the context of a widespread attack on the region's civilian population[57] and suffered mass murder, rape, imprisonment in camps, as well as the destruction of cultural sites and private property. This was often followed by anti-Bosniak propaganda, particularly in the municipalities of Vitez, Busovača, Novi Travnik and Kiseljak. Ahmići massacre in April 1993, was the culmination of the Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing, resulting in mass killing of Bosnian Muslim civilians just in a few hours. An estimate puts the death toll at 120. The youngest was a three-month-old baby, who was shot to death in his crib, and the oldest was a 96-year-old woman. It is the biggest massacre committed during the conflict between Croats and the Bosnian government (dominated by Bosniaks).

The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) has ruled that these crimes amounted to crimes against humanity in numerous verdicts against Croat political and military leaders and soldiers, most notably Dario Kordić. [58] Based on the evidence of numerous HVO attacks at that time, the ICTY Trial Chamber concluded in the Kordić and Čerkez case that by April 1993 Croat leadership had a common design or plan conceived and executed to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley. Dario Kordić, as the local political leader, was found to be the planner and instigator of this plan. [59] According to the Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Center (IDC), around 2,000 Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley are missing or were killed during this period.[60]

War in Herzegovina

The Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia took control of many municipal governments and services in Herzegovina as well, removing or marginalising local Bosniak leaders. Herzeg-Bosnia took control of the media and imposed Croatian ideas and propaganda. Croatian symbols and currency were introduced, and Croatian curricula and the Croatian language were introduced in schools. Many Bosniaks and Serbs were removed from positions in government and private business; humanitarian aid was managed and distributed to the Bosniaks' and Serbs' disadvantage; and Bosniaks in general were increasingly harassed. Many of them were deported into concentration camps: Heliodrom, Dretelj, Gabela, Vojno and Šunje.

Up till 1993 the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) and Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) had been fighting side by side against the superior forces of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) in some areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even though armed confrontation and events like the Totic kidnappings strained the relationship between the HVO and ARBiH the Croat-Bosniak alliance held in Bihać pocket (northwest Bosnia) and the Bosanska Posavina (north), where both were heavily outmatched by Serb forces.

According to ICTY judgment in Naletilić-Martinović case Croat forces attacked the villages of Sovici and Doljani, about 50 kilometers north of Mostar in the morning on April 17, 1993. The attack was part of a larger HVO offensive aimed at taking Jablanica, the main Bosnian Muslim dominated town in the area. The HVO commanders had calculated that they needed two days to take Jablanica. The location of Sovici was of strategic significance for the HVO as it was on the way to Jablanica. For the Bosnian Army it was a gateway to the plateau of Risovac, which could create conditions for further progression towards the Adriatic coast. The larger HVO offensive on Jablanica had already started on April 15, 1993. The artillery destroyed the upper part of Sovici. The Bosnian Army was fighting back, but at about five p.m. the Bosnian Army commander in Sovici, surrendered. Approximately 70 to 75 soldiers surrendered. In total, at least 400 Bosnian Muslim civilians were detained. The HVO advance towards Jablanica was halted after a cease-fire agreement had been negotiated. [61]

Siege of Mostar

Mostar was surrounded by the Croat forces for nine months, and much of its historic city was severely damaged in shelling including the famous Stari Most bridge.[62]

Mostar was divided into a Western part, which was dominated by the Croat forces and an Eastern part where the Army of Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was largely concentrated. However, the Bosnian Army had its headquarters in West Mostar in the basement of a building complex referred to as Vranica. In the early hours of May 9, 1993, the Croatian Defence Council attacked Mostar using artillery, mortars, heavy weapons and small arms. The HVO controlled all roads leading into Mostar and international organisations were denied access. Radio Mostar announced that all Bosniaks should hang out a white flag from their windows. The HVO attack had been well prepared and planned.[63]

The Croats took over the west side of the city and expelled thousands[62] Bosniaks from the west side into the east side of the city. The HVO shelling reduced much of the east side of Mostar to rubble. The JNA (Yugoslav Army) demolished Carinski Bridge, Titov Bridge and Lucki Bridge over the river excluding the Stari Most. HVO forces (and its smaller divisions) engaged in a mass execution, ethnic cleansing and rape on the Bosniak people of the West Mostar and its surrounds and a fierce siege and shelling campaign on the Bosnian Government run East Mostar. HVO campaign resulted in thousands of injured and killed.[62]

Bosnian Army launched an operation known as Neretva 93 against the Croatian Defence Council and Croatian Army in September 1993 in order to end the siege of Mostar and to recapture areas of Herzegovina, which were included in self-proclaimed Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia. The operation was stopped by Bosnian authorities after it received the information about the massacre against Croat civilians and POWs in the villages of Grabovica and Uzdol.

The Croat leadership (Jadranko Prlić, Bruno Stojić, Slobodan Praljak, Milivoj Petković, Valentin Ćorić and Berislav Pušić) is presently on trial at the ICTY on charges including crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva conventions and violations of the laws or customs of war. Dario Kordić, political leader of Croats in Central Bosnia was convicted of the crimes against humanity in Central Bosnia i.e. ethnic cleansing and sentenced to 25 years in prison. [58] Bosnian commander Sefer Halilović was charged with one count of violation of the laws and customs of war on the basis of superior criminal responsibility of the incidents during Neretva 93 and found not guilty.

In an attempt to protect the civilians, UNPROFOR's role was further extended in 1993 to protect the "safe havens" that it had declared around Sarajevo, Goražde, Srebrenica, Tuzla, Žepa and Bihać.

1994

In 1994, NATO became actively involved, when its jets shot down four Serb aircraft over central Bosnia on February 28 1994 violating the UN no-fly zone.

The Croat-Bosniak war officially ended on February 23, 1994 when the Commander of HVO, general Ante Roso and commander of Bosnian Army, general Rasim Delić, signed a ceasefire agreement in Zagreb. In March 1994 a peace agreement mediated by the USA between the warring Croats (represented by the Republic of Croatia) and the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was signed in Washington and Vienna which is known as the Washington Agreement. Under the agreement, the combined territory held by the Croat and Bosnian government forces was divided into ten autonomous cantons, establishing the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This effectively ended the war between Croats and Bosniaks, and narrowed the warring parties down to two.

1995

The war continued through most of 1995.

In July 1995. Serb troops under general Ratko Mladić, occupied the UN "safe area" of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia where around 8,000 men were killed (most women were expelled to Bosniak-held territory and some of them were killed and raped).[64] The ICTY ruled this event as genocide in the case Prosecutor vs. Krstić.

In line with the Croat-Bosniak agreement, Croatian forces operated in western Bosnia (Operation Summer '95) and in early August launched Operation Storm, taking over the Serb Krajina in Croatia. With this, the Bosniak-Croat alliance gained the initiative in the war, taking much of western Bosnia from the Serbs in several operations, including: Mistral and Sana. These forces now came to threaten the Bosnian Serb capital Banja Luka with direct ground attack.

Serb forces committed few major massacres during 1995 : first Markale massacre, Tuzla massacre (on May 25th), second Markale massacre and Srebrenica massacre.

The second Markale massacre occurred and NATO responded by opening wide air strikes against Bosnian Serb infrastructure and units in September.

At that point, the international community pressured Milošević, Tuđman and Izetbegović to the negotiation table and finally the war ended with the Dayton Peace Agreement signed on November 21, 1995. The final version of the peace agreement was signed December 14, 1995 in Paris.

Casualties

| Total 102,622 |

Bosniaks & Croats | c. 72,000 |

| Serbs | c. 30,700 | |

| Total civilians 55,261 |

Bosniaks & Croats | c. 38,000 |

| Serbs | c. 16,700 | |

| Total soldiers 47,360 |

Bosniaks | c. 28,000 |

| Serbs | c. 14,000 | |

| Croats | c. 6,000 |

| Total 96,175 |

Bosniaks | 63,994 | 66.5% |

| Serbs | 24,206 | 25.2% | |

| Croats | 7,338 | 7.6% | |

| other | 637 | 0.7% | |

| Total civilians 38,645 |

Bosniaks | 32,723 | 84.7% |

| Serbs | 3,555 | 9.2% | |

| Croats | 1,899 | 4.9% | |

| others | 466 | 1.2% | |

| Total soldiers 57,529 |

Bosniaks | 31,270 | 54.4% |

| Serbs | 20,649 | 35.9% | |

| Croats | 5,439 | 9.5% | |

| others | 171 | 0.3% | |

| unconfirmed | 4,000 |

The death toll after the war was originally estimated at around 200,000 by the Bosnian government and NATO. They also recorded around 1,326,000 refugees and exiles.

On June 21 2007, the Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo published the most extensive research on Bosnia-Herzegovina's war casualties titled: The Bosnian Book of the Dead - a database that reveals 97,207 names of Bosnia and Herzegovina's citizens killed and missing during the 1992-1995 war. An international team of experts evaluated the findings before they were released. More than 240,000 pieces of data have been collected, processed, checked, compared and evaluated by international team of experts in order to get the final number of more than 97,000 of names of victims, belonging to all nationalities. Recent research have shown that most of the 97,207 [11] documented casualties (soldiers and civilians) during Bosnian War were Bosniaks (65%), with Serbs in second (25%) and Croats (8%) in third place. However, 83 percent of civilian victims were Bosniaks, 10 percent were Serbs and more than 5 percent were Croats, followed by a small number of others such as Albanians or Romani people. The total figure of dead could rise by a maximum of another 10,000 for the entire country due to ongoing research. [14] [15][17] Further research is ongoing.

There are no precise statistics dealing with the casualties of the Croat-Bosniak conflict along ethnic lines. The RDC's data on human losses in the regions caught in the Croat-Bosniak conflict as part of the wider Bosnian War, however, can serve as a rough approximation. According to this data, in Central Bosnia most of the 10,448 documented casualties (soldiers and civilians) were Bosniaks (62%), with Croats in second (24%) and Serbs (13%) in third place. It should be noted that the municipalities of Gornji Vakuf and Bugojno also geographically located in Central Bosnia (known as Gornje Povrbasje region), with the 1,337 documented casualties are not included in Central Bosnia statistics, but in Vrbas region. Anyway, around 80% of the casualties from Gornje Povrbasje were Bosniaks. In the region of Neretva river of 6,717 casualties, 54% were Bosniaks, 24% Serbs and 21% Croats. The casualties in those regions were mostly but not exclusively the consequence of Croat-Bosniak conflict. To a lesser extent the conflict with the Serbs also resulted in a number of casualties included in the statistics. For instance, a number of Serbs were massacred by Croat forces in June 1992 in the village of Čipuljić located in Bugojno municipality.[65]

Large discrepancies in all these estimates are generally due to the inconsistent definitions of who can be considered victims of the war. Some research calculated only direct casualties of the military activity while other also calculated indirect casualties, such as those who died from harsh living conditions, hunger, cold, illnesses or other accidents indirectly caused by the war conditions. Original higher numbers were also used as many victims were listed twice or three times both in civilian and military columns as little or no communication and systematic coordination of these lists could take place in wartime conditions. Manipulation with numbers is today most often used by historical revisionist to change the character and the scope of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, most of above independent studies have not been accredited by either government involved in the conflict and there are no single official results that are acceptable to all sides.

It should not be discounted that there were also significant casualties on the part of International Troops in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Some 320 soldiers of UNPROFOR were killed during this conflict in Bosnia.

War crimes

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing was a common phenomenon in the war. This typically entailed intimidation, forced expulsion and/or killing of the undesired ethnic group as well as the destruction or removal of the physical vestiges of the ethnic group, such as places of worship, cemeteries and cultural and historical buildings. As well as the frequent use of torture, rape and ritualistic killing, most commonly throat slitting by the Serbs: The murderer binds the victim's hands behind his or her back and forces the victim to kneel on the ground. The murderer then jabs his knee into the center of the victim's back, grabs the top of the victim's head by the hair, pulls the victims head back, and slits the victims throat with his knife.[66] According to numerous ICTY verdicts, Serb[67] and Croat[58] forces performed ethnic cleansing of their territories planned by their political leadership in order to create ethnically pure states (Republika Srpska and Herzeg-Bosnia). Furthermore, Serb forces committed genocide in Srebrenica at the end of the war.[68]

Based on the evidence of numerous HVO attacks, the ICTY Trial Chamber concluded in the Kordić and Čerkez case that by April 1993 Croat leadership had a common design or plan conceived and executed to ethnically cleanse Bosniaks from the Lašva Valley in Central Bosnia. Dario Kordić, as the local political leader, was found to be the planner and instigator of this plan. [59]

Mass rape and psychological oppression

During the Bosnian war, Serb forces conducted sexual abuse strategy on Bosnian Muslim girls and women which will later be known as mass rape phenomenon. Between 20,000 and 44,000 women were systematically raped by the Serb forces. Considering the estimates and the demographics of Bosnia, by the end of the war approximately up to seven out of every hundred sexually capable Bosniak women and girls had been raped by Serb forces. The women and young girls were often held captives for up to 8 months or more, before being released or killed, often strategically beyond the possibility of abortion. During this time they were kept under constant fear, trauma, threat, violence, oppression, humiliation, sexual abuse and slavery by soldiers in ages ranging from 20 to 60 years.

Common profound complications among surviving women and girls include gynaecological, physical and psychological (post traumatic) disorders, as well as unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases. The survivors often feel uncomfortable/frustrated/sickened with men, sex and relationships; ultimately affecting the growth/development of a population and/or society as such (thus constituting a slow genocide according to some). In accordance with the Muslim society, most of the girls not married were virgins at the time of rape; further traumatizing the situation. Mass rapes were mostly done in Eastern Bosnia (during Foča massacres), and in Grbavica during the Siege of Sarajevo. Women and girls were kept in various detention centres where they had to live in intolerably unhygienic conditions and were mistreated in many ways including being repeatedly raped. Serb soldiers or policemen would come to these detention centres, select one or more women, take them out and rape them. All this was done in full view, in complete knowledge and sometimes with the direct involvement of the Serb local authorities, particularly the police forces. The head of Foča police forces, Dragan Gagović, was personally identified as one of the men who came to these detention centres to take women out and rape them. There were numerous rape camps in Foča. "Karaman's house" was one of the most notable rape camps. While kept in this house, the girls were constantly raped. Among the women held in "Karaman's house" there were minors as young as 12 and 14 years of age. [31][36][69]

Muslim women were specifically targeted as the rapes against them were one of the many ways in which the Serbs could assert their superiority and victory over the Bosniaks. For instance, the girls and women, who were selected by convicted war criminal Dragoljub Kunarac or by his men, were systematically taken to the soldiers’ base, a house located in Osmana Đikić street no 16. There, the girls and women, who Kunarac knew were civilians, were raped by his men or by the convicted himself. Some of the girls were just 14. Serb soldiers demonstrated a total disregard for Bosniak in general, and Bosniak women in particular. Serb soldiers removed many Muslim girls from various detention centres and kept some of them for various periods of time for him or his soldiers to rape.[31]

The other example includes Radomir Kovač,convicted also by ICTY. While four girls were kept in his apartment, the convicted Radomir Kovač abused them and raped three of them many times, thereby perpetuating the attack upon the Bosnian Muslim civilian population. Kovač would also invite his friends to his apartment, and he sometimes allowed them to rape one of the girls. Kovač also sold three of the girls. Prior to their being sold, Kovač had given two of these girls, to other Serb soldiers who abused them for more than three weeks before taking them back to Kovač, who proceeded to sell one and give the other away to acquaintances of his.[31]

The mass-rape events in Bosnia inspired the Golden Bear winner at the 56th Berlin International Film Festival in 2006, called Grbavica.

Genocide

A trial took place before the International Court of Justice, following a 1993 suit by Bosnia and Herzegovina against Serbia and Montenegro alleging genocide (see Bosnian genocide case at the International Court of Justice). The International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling of 26 February 2007 determined that Serbia had no responsibility for the genocide committed by Bosnian Serb forces in Srebrenica massacre in 1995. The ICJ concluded, however, that Serbia failed to act to prevent the Srebrenica massacre and failed to punish those believed to be responsible, especially general Ratko Mladić. Finally, the court concluded that there was not sufficient evidence to find that there had been a wider genocide committed against the Bosniak population, as alleged by the Bosnian government.[70]

In popular culture

The Bosnian War has been depicted in a number of films including Hollywood movies such as The Hunting Party, about an attempt at catching the accused war criminal Radovan Karadžić, Behind Enemy Lines and Savior, a number of British movies such as Welcome to Sarajevo, which is about the life of Sarajevo citizens during the siege and an award-winning British television drama, Warriors, aired on BBC One in 1999 about the Lašva Valley ethnic cleansing. The Polish film "Demony wojny" ("Demons of War", 1998), set during the Bosnian conflict, portrays a Polish group of IFOR soldiers who accidentally come to help a pair of journalist tracked by a local warlord whose crimes they had taped. Bosnian director Danis Tanović's No Man's Land won the Best Foreign Language Film awards at the 2001 Academy Awards and the 2002 Golden Globes. Grbavica, about the life of a single mother in contemporary Sarajevo in the aftermath of systematic rape of Bosniak women by Serbian troops during the war, won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival. Documentaries include Bernard-Henri Lévy's Bosna! about Bosnian resistance against well equipped Serbian troops at the beginning of the war, Slovenian documentary Tunel upanja (A Tunnel of Hope) about the Sarajevo Tunnel constructed by the besieged citizens of Sarajevo in order to link the city of Sarajevo, which was entirely cut-off by Serbian forces, with the Bosnian government territory and British documentary A Cry from the Grave about the Srebrenica massacre, as well as BBC's lengthy series "The Death of Yugoslavia", documenting the outbreak of the war from the earliest roots of the conflict, in the 1980s. A number of Western films made the Bosnian conflict the background of their stories - some of those include "Avenger", based on Frederick Forsyth's novel in which a mercenary tracks down a Serbian warlord responsible for war crimes, and "The Peacemaker", in which a Serbian activist emotionally devastated by the losses of war plots to take revenge on the United Nations by exploding a nuclear bomb in New York.

Plays about the war include Necessary Targets, written by Eve Ensler.

Savatage recorded a concept album entitled Dead Winter Dead, which was set in the Balkan War. One of the songs from this album, "Christmas Eve in Sarajevo", also appears on the first album by the Trans Siberian Orchestra.[71]

In the video game Grand Theft Auto 4, the protagonist Niko Belić is a Bosnian Serb veteran of the Bosnian War.

Dampyr is an Italian comic book, created by Mauro Boselli and Maurizio Colombo and published in Italy by Sergio Bonelli Editore about Harlan Draka, half human, half vampire, who wages war on the multifaceted forces of Evil. The first two episodes are located in Sarajevo during the Bosnian war. The war in Eastern Bosnia is a subject of Joe Sacco's comic book Safe Area Goražde.

A book on the Bosnian War called "My WarGone by,I Miss it so" by Anthony Loyd depicts the view of a freelance war photographer.

Galleries

Gallery of maps

Notes

- ↑ "ICTY: Conflict between Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia".

- ↑ "ICTY: Conflict between Bosnia and Croatia".

- ↑ "ICJ: The genocide case: Bosnia v. Serbia - See Part VI - Entities involved in the events 235-241" (PDF).

- ↑ "Courte: Serbia failed to prevent genocide, UN court rules". Associated Press (2007-02-26).

- ↑ "Sense Tribunal: SERBIA FOUND GUILTY OF FAILURE TO PREVENT AND PUNISH GENOCIDE".

- ↑ Statement of the President of the Court

- ↑ "Dayton Peace Accords on Bosnia". US Department of State (1996-03-30). Retrieved on 2006-03-19.

- ↑ "War-related Deaths in the 1992–1995 Armed Conflicts in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Critique of Previous Estimates and Recent Results", European Journal of Population (June 2005).

- ↑ "Research halves Bosnia war death toll to 100,000", Reuters (November 23, 2005).

- ↑ "Review of European Security Issues", U.S. Department of State (28 April 2006).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 RDC - Casualties Research Results - June 2007 [1]

- ↑ Bosnia’s “Book of the Dead”, Institute for War and Peace Reporting, June 23, 2007

- ↑ estimated from RDC:[2]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Research shows estimates of B&H death toll inflated - IHT: The Bosnian Book of Dead

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bosnia's Book of Dead - BIRN Report

- ↑ [3] - RFE: Svaka žrvat ima svoje ime

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Research and Documentation Center; "The Status of Database by the Centers"; current - January 2007 [4]

- ↑ C.I.A. Report on Bosnia Blames Serbs for 90% of the War Crimes by Roger Cohen, The New York Times, March 9, 1995

- ↑ New York Times - Karadzic Sent to Hague for Trial Despite Violent Protest by Loyalists [5]

- ↑ ICTY cases, indictments and proceedings [6]

- ↑ "ICTY: Naletilić and Martinović verdict - A. Historical background".

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "ICTY: Blaškić verdict - A. The Lasva Valley: May 1992 – January 1993t".

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "ICTY: Prlić et al. (IT-04-74)".

- ↑ "VOA: U Federaciji BiH obilježen Dan nezavisnosti BiH".

- ↑ de Krnjevic-Miskovic, Damjan. "[http:// inthenationalinterest.com/Articles/Vol2Issue41/Vol2Issue41dkm.html Alija Izetbegovic, 1925-2003]". In the National Interest. Retrieved on 2008-08-28.

- ↑ UK Guardian: America used Islamists to arm the Bosnian Muslims

- ↑ Vjesnik: Je li Tuta platio atentatorima po pet tisuća maraka[7]

- ↑ Helena Smith, Greece faces shame of role in Serb massacre, The Observer, 5 January 2003, accessed 25 November 2006

- ↑ Nacional: Šveđanin priznao krivnju za ratne zločine u BiH [8]

- ↑ United States Institute of Peace, Dayton Implementation: The Train and Equip Program, September 1997 | Special Report No. 25

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 "ICTY: The attack against the civilian population and related requirements".

- ↑ "ICTY: Greatest suffering at least risk".

- ↑ HRW-[9]

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - Political developments in the Municipality of Prijedor before 30 April 1992 takeover".

- ↑ CCPR Human Rights Committee. "Bosnia and Herzegovina Report". United Nations. 30 October 1992 [10]

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "The Society for Threatened Peoples (GfbV): Documentation about war crimes - Tilman Zülch".

- ↑ Odjek - revija za umjetnost i nauku - Zločin silovanja u BiH - [11]

- ↑ ICTY: Krnojelac verdict - [12]

- ↑ Massachusetts Institute of Tehnology-short time line of Yugoslav war with number of rapes

- ↑ The Independent (London): Film award forces Serbs to face spectre of Bosnia's rape babies - [13]

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - The takeover of power by Serbs in the Municipality of Prijedor on 29/ 30 April 1992".

- ↑ "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - The camps: Keraterm, Omarska and Trnopolje".

- ↑ "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - Keraterm".

- ↑ "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - Omarska".

- ↑ "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - Trnopolje".

- ↑ "ICTY: Milomir Stakić judgement - 4. Interrogations, beatings and sexual assaults in the camps- Trnopolje".

- ↑ Pessimism Is Overshadowing Hope In Effort to End Yugoslav Fighting

- ↑ ICTY - Kordic and Cerkez judgment - II. PERSECUTION: THE HVO TAKE-OVERS B. Novi Travnik - [14]

- ↑ Sarajevo, i poslije, Erich Rathfelder, München 1998 [15]

- ↑ Angus Macqueen and Paul Mitchell, The Death of Yugoslavia, [16]

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict - IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - 2. The Conflict in Gornji Vakuf".

- ↑ "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict - IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - 4. Role of Dario Kordić".

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: Poziv na predaju".

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: Ko je počeo rat u Gornjem Vakufu".

- ↑ "SENSE Tribunal: "James Dean" u Gornjem Vakufu".

- ↑ "ICTY (1995): Initial indictment for the ethnic cleansing of the Lasva Valley area - Part II".

- ↑ "ICTY: Summary of sentencing judgement for Miroslav Bralo".

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict".

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "ICTY: Kordić and Čerkez verdict - IV. Attacks on towns and villages: killings - C. The April 1993 Conflagration in Vitez and the Lašva Valley - 3. The Attack on Ahmići (Paragraph 642)".

- ↑ "IDC: Victim statistics in Novi Travnik, Vitez, Kiseljak and Busovača".

- ↑ ICTY (Naletilic-Matinovic): 1. Sovici and Doljani- the attack on 17 April 1993 and the following days [17]

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 "ICTY: Prlić et al. (IT-04-74)".

- ↑ "ICTY: Naletilić and Martinović verdict - Mostar attack".

- ↑ "ICTY: Krstić verdict" (PDF).

- ↑ RDC - Research results (2007) - Human Losses in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1991-1995 [18]

- ↑ Situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and Yugoslavia

- ↑ "ICTY: Radoslav Brđanin judgement".

- ↑ ICTY; "Address by ICTY President Theodor Meron, at Potočari Memorial Cemetery" The Hague, 23 June 2004 [19]

- ↑ 030306IA

- ↑ ICJ press release 2007/8 26 February 2007

- ↑ allmusic ((( Dead Winter Dead > Overview )))

Bibliography

- Howard, Les "Winter Warriors - Across Bosnia with the PBI", ISBN 978-1846240775 Critical account of a Peacekeeper's contribution to the end of the war

- Gutman, Roy, A Witness to Genocide: The 1993 Pulitzer Prize-Winning Dispatches on the "Ethnic Cleansing" of Bosnia, ISBN 978-0020329954

- Macqueen, Angus; Mitchell, Paul, The Death of Yugoslavia, [20]

- Hoare, Marko Attila, How Bosnia Armed Saqi Books, 2004, ISBN 978-0863563676

- Cigar, Norman, Genocide in Bosnia: The Politics of Ethnic Cleansing, Texas A&M University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-1585440047

- Shrader, Charles R. The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia Texas A&M University Press, 2003 ISBN 1-58544-261-5

- Simms, Brendan. Unfinest Hour: Britain and the Destruction of Bosnia. Penguin, 2003. ISBN 0-14-028983-6

- Raguz, Vitomir Miles. Who Saved Bosnia Naklada Stih, 2005 ISBN 953-6959-28-3

- Beloff, Nora. Yugoslavia: An Avoidable War. New European Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-872410-08-1

- Loyd, Anthony. "My War Gone By, I Miss It So." Penguin, 1999. ISBN 0-14-029854-1

- Maas, Peter. Love Thy Neighbor: A Story of War. Vintage Books, 1996. ISBN 0-679-76389-9

- Dr. R. Craig Nation. "War in the Balkans 1991-2002." Strategic Studies Institute, 2002, ISBN 1-58487-134-2 [21]

- Srebrenica, Potocari, [22]

See also

- Croat-Bosniak war

- Cvetković-Maček Agreement

- 1991 Bosnia and Herzegovina Population Census

- Bosnian Genocide

- Command responsibility

- High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Keraterm camp

- Manjača camp

- Markale massacres

- Mass rape in the Bosnian War

- Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Mujahideen in the Bosnian war

- Omarska camp

- Operation Deliberate Force

- Peace plans offered before and during the Bosnian War

- Religious war

- Serb propaganda

- Siege of Sarajevo

- Srebrenica massacre

- Trnopolje camp

- The role of foreign fighters in the Bosnian war

- Mrkonjić Grad incident (June 1995)

- Banja Luka incident

- Operation Bøllebank

- Operation Amanda

- Operation Sana

- Role of Serb media in the 1991-1999 wars in the former Yugoslavia

External links

- Summary of the ICTY verdicts related to the conflict between Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

- Summary of the ICTY verdicts related to the conflict between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia

- List of people missing from the war

- Stanislav Galic judgement

- Srebrenica 1994

- UN report on prison camps during the war

- Open UN document on Serb attrocities towards non-Serbs

- Genocide in Yugoslavia

- Serbian War Crime Testimonies

- Interview with Haris Silajdzic

- WAR IN THE BALKANS, 1991-2002 - 4. The Land of Hate: Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1992-95, R. Craig Nation (2003)

Related films

- Warriors at the Internet Movie Database

- The Death of Yugoslavia at the Internet Movie Database - Part III. The Struggle for Bosnia.

- The Death of Yugoslavia Part I (Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian)

- English documentary on the Bosnian War (The resistance of Bosnia was heard up to the skies)

| Yugoslav wars | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | Timeline | Participants | People |

|

Wars and conflicts

Background:

Consequences:

Articles on nationalism:

|

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1999 2001 |

Local states:

Unrecognised states and entities:

Armies:

Military formations and volunteers:

External states: |

Politicians:

Top military commanders:

Other notable commanders:

Key foreign figures: |