Bordeaux wine

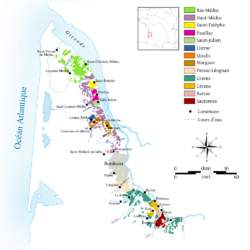

A Bordeaux wine is any wine produced in the Bordeaux region of France. Average vintages produce over 700 million bottles of Bordeaux wine, although in good vintages, this total can exceed over 900 million, ranging from large quantities of everyday table wine, to some of the most expensive and prestigious wines in the world. 88% of wine produced in Bordeaux is red (usually referred to as Claret), with notable sweet white wines such as Chateau Y'Quem, dry white's, rosé and sparkling wines (Crémant de Bordeaux) all making up the remainder. Bordeaux wine is made by 10,000 producers or châteaux from the grapes of 13,000 grape growers. There are 57 appellations of Bordeaux wine.

Contents |

History

The history of wine production seems to have begun sometime after 48 AD, during the Roman occupation of St. Émilion, when the Romans established vineyards to cultivate wine for the soldiers.[1] However, it is only in 71 AD that Pliny recorded the first real evidence of vineyards in Bordeaux.[2] France's first extensive vineyards were established by Rome in around 122 BC in today's Languedoc, the better part of two hundred years earlier.[3]

Although domestically popular, French wine was seldom exported, as the areas covered by vineyards and the volume of wine produced was low. In the 12th century however, the popularity of Bordeaux wines increased dramatically following the marriage of Henry Plantagenet and Aliénor d’Aquitaine.[4] The marriage made the province of Aquitaine English territory, and thenceforth the majority of Bordeaux was then exported[4] This accounts for the ubiquity of claret in England.

As the popularity of Bordeaux wine increased, the vineyards expanded to accommodate the demands from abroad. Being the land tax beneficiary, Henry II was in favor of this industry, and to increase it further, abolished export taxes to England from the Aquitaine region. In the 13th and 14th century, a code of business practices called the police des vins emerged to give Bordeaux wine a distinct trade advantage over its neighboring regions.[5]

The export of Bordeaux was effectively halted by the outbreak of The Hundred Years' War between France and England in 1337.[4] By the end of the conflict in 1453 France had repossessed the province, thus taking control of wine production in the region.[4]

In 1725, the spread of vineyards throughout Bordeaux was so vast that it was divided into specific areas so that the consumer could tell exactly where each wine was from. The collection of districts was known as the Vignoble de Bordeaux, and bottles were labeled with both the region and the area from which they originated.

From 1875-1892 almost all Bordeaux vineyards were ruined by Phylloxera infestations.[4] The region's wine industry was rescued by grafting native vines on to pest-resistant American rootstock and all Bordeaux vines that survive to this day are a product of this action[4] This is not to say that all contemporary Bordeaux wines are truly American wines, as rootstock does not affect the production of grapes.

Due to the lucrative nature of this business, other areas in France began growing their own wines and labeling them as Bordeaux products. As profits in the Aquitaine region declined, the vignerons demanded that the government impose a law declaring that only produce from Bordeaux could be labeled with this name. The Institut National des Appellations d'Origine (INAO) was created for this purpose.[4]

In 1936, the government responded to the appeals from the winemakers and stated that all regions in France had to name their wines by the place in which they had been produced. Labeled with the AOC approved stamp, products were officially confirmed to be from the region that it stated. This law later extended to other goods such as cheese, poultry and vegetables.[4]

The economic problems in 1970s, in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis marked a difficult period for Bordeaux. The 1980s was a period of recovery, and a new era in two respects. First, wine critics (rather than just official classifications) started to have an influence on demand and prices. US wine critic Robert M. Parker, Jr.'s review of the 1982 Bordeaux vintage has generally been considered to have started this trend, and Parker has remained the most influential Bordeaux critic ever since. Second, the preferred style of high-quality red Bordeaux has gradually changed: the wines are more concentrated in flavour, have a heavier influence of new oak, are more approachable already when young, and are slightly higher in alcohol. It has been claimed that this is the style of wine that Parker prefers and gives high scores to (and they are therefore sometimes called "Parkerized"), while the Pomerol-based winemaking consultant Michel Rolland writes the recipe for how to make these wines.

Bordeaux used to have a significant production of white wines, with Entre-deux-Mers, a primarily white wine area. Unlike the style of dry white Bordeaux favoured today, with almost 100% Sauvignon Blanc and a heavy influence of new oak, the traditional Entre-deux-Mers whites had a high proportion of Semillion and were either made in old oak barrels or in steel tanks. Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, these vineyards were converted to red wine production (of Bordeaux AOC and Bordeaux Superieur AOC), and the production of white wine has decreased ever since. Today production of white wine has shrunk to about one tenth of Bordeaux's total production.

Climate and geography

The Bordeaux region of France is the second largest wine-growing area in the world with 287,037 acres (1,162 km2) or 116,160 ha's under vine. Only the Languedoc wine region with 617,750 acres (2,500 km2) under vine is larger.[6] Located halfway between the North pole and the equator, there is more vineyard land planted in Bordeaux than in all of Germany and ten times the amount planted in New Zealand.[7]

The major reason for the success of winemaking in the Bordeaux region is the excellent environment for growing vines. The geological foundation of the region is limestone, leading to a soil structure that is heavy in calcium. The Gironde estuary dominates the regions along with its tributaries, the Garonne and the Dordogne rivers, and together irrigate the land and provide with an Atlantic Climate, (or in American rather than plain English) oceanic climate for the region.[7]

These rivers define the main geographical subdivisions of the region:

- "The right bank", situated on the right bank of Dordogne, in the northern parts of the region, around the city of Libourne.

- Entre-deux-mers, French for "between two waters", the area between the rivers Dordogne and Garonne, in the centre of the region.

- "The left bank", situated on the left bank of Garonne, in the west and south of the region, around the city of Bordeaux itself. The left bank is further subdivided into:

- Graves, the area upstream of the city Bordeaux.

- Médoc, the area downstream of the city Bordeaux, situated on a peninsula between Gironde and the Atlantic.

In Bordeaux the concept of terroir plays a pivotal role in wine production with the top estates aiming to make terroir driven wines that reflect the place they are from, often from grapes collected from a single vineyard.[8] The soil of Bordeaux is composed of gravel, sandy stone, and clay. The region's best vineyards are located on the well drained gravel soils that are frequently found near the Gironde river. An old adage in Bordeaux is the best estates can "see the river" from their vineyard and majority of land that face riverside are occupied by classified estates.[9]

Grapes

Red Bordeaux, which is traditionally known as claret in the United Kingdom, is generally made from a blend of grapes. Permitted grapes are Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Petit Verdot, Malbec, and Carmenere. Today Malbec and Carmenere are rarely used, with Château Clerc Milon, a fifth growth Bordeaux, being one of the few to still retain Carmenere vines.

As a very broad generalization, Cabernet Sauvignon (Bordeaux's second-most planted grape variety) dominates the blend in red wines produced in the Médoc and the rest of the left bank of the Gironde estuary. Typical top-quality Chateaux blends are 70% Cabernet Sauvignon, 15% Cabernet Franc & 15% Merlot. Merlot (Bordeaux's most-planted grape variety) and to a lesser extent Cabernet Franc (Third most planted variety) tend to predominate in Saint Emilion, Pomerol and the other right bank appellations. These Right Bank blends from top-quality Chateaux are typically 70% Merlot, 15% Cabernet Franc & 15% Cabernet Sauvignon. [10]

White Bordeaux is predominantly, and exclusively in the case of the sweet Sauternes, made from Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscadelle - Typical blends are usaully 80% Sémillon, 20% Sauvignon Blanc. As with the reds, white Bordeaux wines are usually blends, most commonly of Sémillon and a smaller proportion of Sauvignon Blanc. Other permitted grape varieties are Ugni Blanc, Colombard, Merlot Blanc, Ondenc and Mauzac.

In the late 1960s Sémillon was the most planted grape in Bordeaux. Since then it has been in constant decline although it still is the most common of Bordeaux's white grapes. Sauvignon Blanc's popularity on the other hand has been rising, overtaking Ugni Blanc as the second most planted white Bordeaux grape in the late 1980s and now being grown in an area more than half the size of that of the lower yielding Sémillon.

Wineries all over the world aspire to making wines in a Bordeaux style. In 1988, a group of American vintners formed The Meritage Association to identify wines made in this way. Although most Meritage wines come from California, there are members of the Meritage Association in 18 states and five other countries, including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Israel, and Mexico.

Wine styles

The Bordeaux wine region is divided into subregions including Saint-Émilion, Pomerol, Médoc, and Graves. The 57 Bordeaux appellations and the wine styles they represent are usually categorized into six main families, four red based on the subregions and two white based on sweetness:[11]

- Red Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur. These are the "basic" red Bordeaux wines which are allowed to be produced all over the region, and represent the cheapeast Bordeaux wines. Some are sold by wine merchants under commercial brand names rather than as classical "Châteaux" wines. These wines tend to be fruity, with a rather marginal influence of oak in comparison to "classical" Bordeaux, and produced in a style meant to be drunk young. On about half of the region's surface, this is the only appellation that may be used. Some producers in those location do however produce Bordeaux Superieur in a style more similar to the other red families.

- Red Côtes de Bordeaux. Eight appellations are located in the hilly outskirts of the region, and produce wines where the blend usually is dominated by Merlot. These wines tend to be intermediate between basic red Bordeaux and the more famous appellations of the left and right bank in both style and quality. However, since none of Bordeaux's stellar names are situated in Côtes de Bordeaux, prices tend to be moderate. There is no official classification in Côtes de Bordeaux.[12]

- Red Libourne, or "Right Bank" wines. Around the city of Libourne, 10 appellations produce wines dominated by Merlot with very little Cabernet Sauvignon, the two most famous being Saint Emilion and Pomerol. These wines often have great fruit concentration, softer tannins and are long-lived. Saint-Emilion has an official classification.[13]

- Red Graves and Médoc or "Left Bank" wines. North and south of the city Bordeaux, the most classical parts of Bordeaux is situated, and produce wines dominated by Cabernet Sauvignon, but often with a significant portion of Merlot. These wines are concentrated, tannic, long-lived and most of them meant to be cellared before drinking. The five First Growths are situated here. There are official classifications for both Médoc and Graves.[14]

- Dry white wines. Dry white wines are made throughout the region, from a blend dominated by Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon, with those from Graves being the most well-known and the only subregion with a classification for dry white wines. The better versions tend to have a significant oak influence.[15]

- Sweet white wines. In several locations and appellations throughout the region, sweet white wine is made from Semillon, Savignon Blanc and Muscadelle grapes affected by noble rot. The best-known of these appellations is Sauternes, which also have an official classification, and where some of the world's most famous sweet wines are produced. There are also appellations neighbouring Sauternes, on both sides of the Garonne river, where similar wines are made.[16]

The vast majority of Bordeaux wine is red, with red wine production out numbering white wine production six to one[17].

Wine classification

There are four different classifications of Bordeaux, covering different parts of the region:[18][19]

- The Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855, covering (with one exception) red wines of Médoc, and sweet wines of Sauternes-Barsac.

- The 1955 Official Classification of St.-Émilion, which is updated approximately once every ten years, and last in 2006.

- The 1959 Official Classification of Graves, initially classified in 1953 and revised in 1959.

- The Cru Bourgeois Classification, which began as an unofficial classification, but came to enjoy official status and was last updated in 2003. However, after various legal turns, the classification was annulled in 2007.[20] As of 2007, plans exist to revive it as an unofficial classification.[21]

The 1855 classification system was made at the request of Emperor Napoleon III for the Exposition Universelle de Paris. This came to be known as the Bordeaux Wine Official Classification of 1855, which ranked the wines into five categories according to price. The first growth red wines (four from Médoc and one, Château Haut-Brion, from Graves), are among the most expensive wines in the world.

The first growths are:

- Château Lafite-Rothschild, in the appellation Pauillac

- Château Margaux, in the appellation Margaux

- Château Latour, in the appellation Pauillac

- Château Haut-Brion, in the appellation Péssac-Legonan

- Château Mouton Rothschild, in the appellation Pauillac, promoted from second to first growth in 1973.

At the same time, the sweet white wines of Sauternes and Barsac were classified into three categories, with only Château d'Yquem being classified as a superior first growth.

In 1955, St. Émilion AOC were classified into three categories, the highest being Premier Grand Cru Classé A with two members:[18]

- Château Ausone

- Château Cheval Blanc

There is no official classification applied to Pomerol. However some Pomerol wines, notably Château Pétrus and Château Le Pin, are often considered as being equivalent to the first growths of the 1855 classification, and often sell for even higher prices.

Commercial aspects

Many of the top Bordeaux wines are primarily sold as futures contracts, called selling en primeur. Because of the combination of longevity, fairly large production, and an established reputation, Bordeaux wines tend to be the most common wines at wine auctions.

Wine label

Bordeaux wine labels generally include [22]-

- The name of estate -(Image example: Château Haut-Batailley)

- The estate's classification -(Image example: Grand Cru Classé en 1855) This can be in reference to the 1855 Bordeaux classification or one of the Cru Bourgeois.

- The appellation -(Image example: Pauillac) Appellation d'origine contrôlée laws dictate that all grapes must be harvested from a particular appellation in order for that appellation to appear on the label. The appellation is a key indicator of the type of wine in the bottle. With the image example, Pauillac wines are always red, and usually Cabernet Sauvignon is the dominant grape.

- Whether or not the wine is bottled at the chateau (Image example: Mis en Bouteille au Chateau) or assembled by a Négociant.

- The vintage -(Image example: 2000)

- Alcohol content - (Image example: 13% vol)

See also

- Garagistes

- Globalization of wine

- Judgment of Paris

External links

- Official Bordeaux Wine website (CIVB)

- Official Bordeaux Classifications

- Bordeaux Wine Guide

- Wine war: Savy New World marketers are devastating the French wine industry

- Robert Parker's Bordeaux vintage chart

References

- ↑ Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine p.50. Simon and Schuster 1989

- ↑ Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine pg 50. Simon and Schuster 1989

- ↑ Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine p.48. Simon and Schuster 1989

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 ."Official Bordeaux website" (2007-04-18).

- ↑ Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine p.149. Simon and Schuster 1989

- ↑ Jancis Robinson, "Oxford Companion to Wine", Second Edition pg 397. Oxford University Press 1999

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 118 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1563054345

- ↑ K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 120 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1563054345

- ↑ K. MacNeil The Wine Bible pg 122 Workman Publishing 2001 ISBN 1563054345

- ↑ Oz Clarke Encyclopedia of Grapes p. 129 Harcourt Books 2001 ISBN 0151007144

- ↑ Bordeaux.com (CIVB): The 57 Appellations, read on January 3, 2008

- ↑ Bordeaux.com (CIVB): The 57 Appellations - Côtes de Bordeaux, read on January 3, 2008

- ↑ Bordeaux.com (CIVB): The 57 Appellations - Saint-Emilion, Pomerol, Fronsac, read on January 3, 2008

- ↑ Bordeaux.com (CIVB): The 57 Appellations - Médoc and Graves, read on January 3, 2008

- ↑ Bordeaux.com (CIVB): The 57 Appellations - Dry white wines, read on January 3, 2008

- ↑ http://www.bordeaux.com/Tout-Vins/Les-Appellations.aspx?SelectedTabMenu=tabVinsBlancOr&culture=en-US&country=OTHERS#TabMenu Bordeaux.com (CIVB): The 57 Appellations - Dry white wines], read on January 3, 2008

- ↑ Hugh Johnson, "The World Atlas of Wine"

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 J. Robinson (ed), "The Oxford Companion to Wine", Third Edition, p 175-177, Oxford University Press 2006, ISBN 0198609906

- ↑ J. Robinson (ed), "The Oxford Companion to Wine", Third Edition, p 212-216, Oxford University Press 2006, ISBN 0198609906

- ↑ Anson, Jane, Decanter (2007-07-10). "Cru Bourgeois classification officially over".

- ↑ Anson, Jane, Decanter (2007-07-27). "Cru Bourgeois to rise again with new name".

- ↑ B. Sanderson "A Master Class in Cabernet" pg 62 Wine Spectator May 15, 2007

Further reading

- Echikson, William. Noble Rot: A Bordeaux Wine Revolution. NY: Norton, 2004.

- Teichgraeber. Bordeaux for less dough. San Francisco chronicle, June 8, 2006 [1]

|

|||||||||||||||||