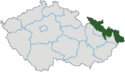

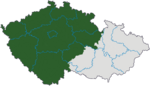

Bohemia

Bohemia (Czech: Čechy;[1] French: Bohème; German: Böhmen; Latin: Bohemia; Polish: Czechy) is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands, currently the Czech Republic. In a broader meaning, it often refers to the entire Czech territory, including Moravia and Czech Silesia,[2] especially in historical contexts, such as the Kingdom of Bohemia.

Bohemia has an area of 52,750 km² and 6.25 million of the Czech Republic's 10.3 million inhabitants. It is bordered by Germany to the southwest, west, and northwest, Poland to the north-east, the Czech historical region of Moravia to the east, and Austria to the south. Bohemia's borders are marked with mountain ranges such as the Bohemian Forest, the Ore Mountains, and the Krkonoše within the Sudeten mountains.

Contents |

History

- Further information: History of the Czech lands and History of Czechoslovakia

Ancient Bohemia

Roman authors provide the first clear reference to this area as Boiohaemum, from Germanic Boi-Heim, "home of the Boii", a Celtic people. As part of the territory often crossed during the Migration Period by major Germanic and Slavic tribes, the western half was conquered and settled from the 1st century BC by Germanic (probably Suebic) peoples including the Marcomanni; the elite of some Boii then migrated west to modern Switzerland and southeastern Gaul. Those Boii that remained in the eastern part were eventually absorbed by the Marcomanni. Part of the Marcomanni, renamed the Bavarians (Baiuvarum), later migrated to the southwest.

After the Bavarian emigration, Bohemia was partially repopulated around the sixth century by the Slavic precursors of today's Czechs, though the exact amount of Slavic immigration is a subject of debate. The Slavic influx was divided into two or (more probably) three waves. The first wave came from the southeast and east, when the Germanic Langobards left Bohemia (circa 568 AD). Later immigrants came from the Black Sea region, as shown by their place names—for example "Dudleb" (today in Prachens region, South Bohemia) is of Iranian origin and "Charvat" is of Turkic origin. Soon after, from the 630s to 660s, the territory was taken by Samo's tribal confederation. His death marked the end of the archaic-"Slavonic" confederation, just the second attempt to establish such a Slavonic union after Carantania in Carinthia.

Other sources (Descriptio civitatum et regionum ad septentrionalem plagam Danubii, Bavaria, 800-850) divide the population of Bohemia at this time into the Merehani, Marharaii, Beheimare (Bohemani) and Fraganeo. (The suffix -ani or -ni means "people of-"). The great tribes of Dudleb, Lemuz and Charvat are missing from this list, which shows a linguistic and cultural shift in favor of Slavonic dialects, a common occurrence in nomadic immigrations. The first religions of these "Bohemians" are unclear, although some Iranian religion-inspired cults (for example, the god Mihr) have been discovered in extant graves (from Pohořelice, Kal, Mikulčice in the 8th century), and a temple of the Fire called Žīži in the center of Fraga. Christianity first appeared in the early 9th century, but became dominant much later, in the 10th or 11th century. The ninth century was crucial for the future of Bohemia - the manorial system sharply declined (as in Bavaria) and the power of central Fraganeo - Czechs grew. It was caused because they kept strategical central cult in their territory. They were predominately Slavs and it contributed to transformation of neighbouring populations into new nation named and led by them with united slavic ethnical subconsciousness. [3]

Přemysl dynasty

Initially, Bohemia was a part of Greater Moravia. The latter which was weakened by years of internal conflict and constant warfare. It ultimately succumbed and fragmented due to the continual incursions of the invading nomadic Magyars and Avars. However, Bohemia's initial incorporation into the Moravian Empire resulted in the extensive Christianization of the population. A native monarchy arose to the throne, and Bohemia came under the rule of the Přemyslid dynasty), which would rule the Czech lands for the next several hundred years.

The Přemyslids secured their frontiers from the remnant asian interlocurs, after the collapse of the Moravian state, by entering into a state of semi-vallage of the Frankish rulers, led by including Charlemagne. Charlemange campaigned extensively against the Avars in the late eighth and early ninth century. This alliance was facilitated by Bohemia's conversion to Christianity, in the ninth century. Continuing close relations were developed with the East Frankish kingdom, which devolved from the Carolingian Empire, into East Francia, and eventually became the Holy Roman Empire. .

After a decisive victory of the Holy Roman Empire and Bohemia over invading Magyars in the 955 Battle of Lechfeld, Boleslaus I of Bohemia was granted the March of Moravia by German emperor Otto the Great. Bohemia would remain a largely autonomous state under the Holy Roman Empire for several decades. The jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Empire was definitively reasserted when Jaromír of Bohemia was granted fief of the Kingdom of Bohemia by Emperor King Henry II of the Holy Roman Empire, with the promise that he hold it as a vassal once he re-occupied Prague with a German army in 1004, ending the rule of Boleslaw I of Poland.

The first to use the title of "King of Bohemia" were the Přemyslid dukes Vratislav II (1085) and Vladislav II (1158), but their heirs would return to the title of duke. The title of king became hereditary under Ottokar I (1198). His grandson Ottokar II (king from 1253–1278) conquered a short-lived empire which contained modern Austria and Slovenia. The mid-thirteenth century saw the beginning of substantial German immigration as the court sought to replace losses from the brief Mongol invasion of Europe in 1241. Germans settled primarily along the northern, western, and southern borders of Bohemia, although many lived in towns throughout the kingdom.

Luxembourg dynasty

The House of Luxembourg accepted the invitation to the Bohemian throne with the crowning of John I of Bohemia in 1310. His son, Charles IV became King of Bohemia in 1346 and founded Charles University in Prague, central Europe's first university, two years later. His reign brought Bohemia to its peak both politically and in total area, resulting in his being the first King of Bohemia to also be elected as Holy Roman Emperor. Under his rule the Bohemian crown controlled such diverse lands as Moravia, Silesia, Upper Lusatia and Lower Lusatia, Brandenburg, an area around Nuremberg called New Bohemia, Luxembourg, and several small towns scattered around Germany.

Hussite Bohemia

During the ecumenical Council of Constance in 1415, Jan Hus, the rector of Charles University and a prominent reformer and religious thinker, was sentenced to be burnt at the stake as a heretic. The verdict was passed despite the fact that Hus was granted formal protection by Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg prior to the journey. Hus was invited to attend the council to defend himself and the Czech positions in the religious court, but with the emperor's approval, he was executed on July 6 1415. The execution of Hus, as well as a papal crusade against followers of Hus, forced the Bohemians to defend themselves. Their stubborn defense and rebellion against Roman Catholics became known as the Hussite Wars.

The uprising against imperial forces was led by a former mercenary, Jan Žižka of Trocnov. As the leader of the Hussite armies, he utilized innovative tactics and weapons, such as howitzers, pistols (from Czech píšťala, the flute), and fortified wagons, which were revolutionary for the time and established Žižka as a great general who never lost a battle.

After Žižka's death, Prokop the Great took over the command for the army, and under his lead the Hussites were victorious for another ten years, to the sheer terror of Europe. The Hussite cause gradually splintered into two main factions, the moderate Utraquists and the more fanatic Taborites. The Utraquists began to lay the ground work for an agreement with the Catholic church and found the more radical views of the Taborites distasteful. Additionally, with general war weariness and yearning for order, the Utraquists were able to eventually defeat the Taborites in the Battle of Lipany in 1434. Sigismund said after the battle that "only the Bohemians could defeat the Bohemians."

Despite an apparent victory for the Catholics, the Bohemian Utraquists were still strong enough to negotiate freedom of religion in 1436. This happened in the so-called Basel Compacts, declaring peace and freedom between Catholics and Utraquists. It would only last for a short period of time, as Pope Pius II declared the Basel Compacts to be invalid in 1462.

In 1458, George of Podebrady was elected to ascend to the Bohemian throne. He is remembered for his attempt to set up a pan-European "Christian League", which would form all the states of Europe into a community based on religion. In the process of negotiating, he appointed Leo of Rozmital to tour the European courts and to conduct the talks. However, the negotiations were not completed, because George's position was substantially damaged over time by his deteriorating relationship with the Pope.

Habsburg Monarchy

After the death of King Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria became King of Bohemia and the country became a constituent state of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Bohemia enjoyed religious freedom between 1436 and 1620, and became one of the most liberal countries of the Christian world during that period of time. In 1609, Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II who made Prague again the capital of the Empire at the time, himself a Roman Catholic, was moved by the Bohemian nobility to publish Maiestas Rudolphina, which confirmed the older Confessio Bohemica of 1575.

After Emperor Ferdinand II began oppressing the rights of Protestants in Bohemia, the resulting Bohemian rebellion resulted in the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618. Elector Frederick V of the Palatinate, a Protestant, was elected by the Bohemian nobility to replace Ferdinand on the Bohemian throne, and was known as the Winter King. Frederick's wife, the popular Elizabeth Stuart and subsequently Elizabeth of Bohemia, known as the Winter Queen or Queen of Hearts, was the daughter of King James I of England. However, after Frederick's defeat in the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, 26 Bohemian estates leaders together with the Jan Jesenius, rector of the Charles University of Prague were executed on the Prague's Old Town Square and the rest were exiled from the country; their lands were then given to Catholic loyalists (mostly of Bavarian and Saxon origin), this ended the pro-reformation movement in Bohemia and also ended the role of Prague as ruling city of the Empire.

Until the so-called "renewed constitution" of 1627, the German language was established as a second official language in the Czech lands. The Czech language remained the first language in the kingdom. Both German and Latin were widely spoken among the ruling classes, although German became increasingly dominant, while Czech was spoken in much of the countryside.

The formal independence of Bohemia was further jeopardized when the Bohemian Diet approved administrative reform in 1749. It included the indivisibility of the Habsburg Empire and the centralization of rule; this essentially meant the merging of the Royal Bohemian Chancellery with the Austrian Chancellery.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the Czech national revivalist movement, in cooperation with part of the Bohemian aristocracy, started a campaign for restoration of the kingdom's historic rights, whereby the Czech language was to replace German as the language of administration. The enlightened absolutism of Joseph II and Leopold II, who introduced minor language concessions, showed promise for the Czech movement, but many of these reforms were later rescinded. During the Revolution of 1848, many Czech nationalists called for autonomy for Bohemia from Habsburg Austria, but the revolutionaries were defeated. The old Bohemian Diet, one of the last remnants of the independence, was dissolved, although the Czech language experienced a rebirth as romantic nationalism developed among the Czechs.

In 1861, a new elected Bohemian Diet was established. The renewal of the old Bohemian Crown (Kingdom of Bohemia, Margraviate of Moravia, and Duchy of Silesia) became the official political program of both Czech liberal politicians and the majority of Bohemian aristocracy ("state rights program"), while parties representing the German minority and small part of the aristocracy proclaimed their loyalty to the centralistic Constitution (so-called "Verfassungstreue"). After the defeat of Austria in the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, Hungarian politicians achieved the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, ostensibly creating equality between the Austrian and Hungarian halves of the empire. An attempt of the Czechs to create a tripartite monarchy (Austria-Hungary-Bohemia) failed in 1871. However, the "state rights program" remained the official platform of all Czech political parties (except for social democrats) until 1918.

Twentieth century

After World War I, Bohemia (as the biggest and most populated land) became the core of the newly-formed country of Czechoslovakia, which combined Bohemia, Moravia, Austrian Silesia, Upper Hungary (present-day Slovakia) and Carpathian Ruthenia into one state. Under its first president, Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia became a rich and liberal democratic republic.

Following the Munich Agreement in 1938, the border regions of Bohemia inhabited predominantly by ethnic Germans (Sudetenland) were annexed to Nazi Germany; this was the only time in Bohemian history that its territory was divided. The remnants of Bohemia and Moravia were then annexed by Germany in 1939, while the Slovak lands became the Slovak Republic, a client state of Nazi Germany. From 1939 to 1945 Bohemia (without the Sudetenland) formed with Moravia the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (Reichsprotektorat Böhmen und Mähren). After World War II ended in 1945, the vast majority of remaining Germans were expelled. After World War II Czechoslovakia was re-established. In 1946, the Communist Party strongly subsidized by the Soviet Union (due to an agreement amongst the Allies, Patton's armies did not enter Prague and the city had to liberate itself before being officially liberated by the Soviet Red Army) won elections. In February 1948 the Communists ousted the remaining democratic ministers in a coup d´état from the government and abolished democratic freedoms.

Beginning in 1949, Bohemia ceased to be an administrative unit of Czechoslovakia, as the country was divided into administrative regions. Between 1949 and 1989 Czechoslovakia (from 1960 officially called Czechoslovak Socialistic Republic) became a Soviet satellite even though there wasn't a Soviet army present (interestingly enough, surrounding countries including Austria were occupied by the Red Army) until Czechoslovak Communist Party started to reform and democratize itself in 1968. This "Prague Spring" process was stopped abruptly by an invasion of 'brotherly' armies of Warsaw Pact in August 1968. In 1989, Agnes of Bohemia became the first saint from a Central European country to be canonized by Pope John Paul II before the "Velvet Revolution" later that year. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1993 (the "Velvet Divorce"), the territory of Bohemia became part of the new Czech Republic.

The Czech constitution from 1992 refers to the "citizens of the Czech Republic in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia" and proclaims continuity with the statehood of the Bohemian Crown. Bohemia is not currently an administrative unit of the Czech Republic. Instead, it is divided into the Prague, Central Bohemian, Plzeň, Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem, Liberec, and Hradec Králové Regions, as well as parts of the Pardubice, Vysočina, South Bohemian and South Moravian Regions.

Famous Products: Bohemian Garnets

Although the Bohemian garnets have been known for many centuries, the industry of mining and cutting them on a large scale is said not to have assumed any special proportions until the advent of foreigners to Karlsbad. They spread a knowledge of the stones to other countries, and a demand sprang up which has led to the establishment of a great industry, and made Bohemia the garnet center of the world.

From the 1880’s the manufacture and distribution of such jewelry was predominately concentrated in large enterprises employing dozens of men and women workers. In total there were over three thousand men employed at the end of the 19th century, in cutting the stones, and if to these be added the number of miners and gold and silver smiths occupied in the mining and mounting of the garnets, a total of ten thousand persons are estimated to have been working in the Bohemian garnet industry around the turn of the 19th century. [4]

See also

- History of the Czech lands

- List of rulers of Bohemia

- Sudetenland

- German Bohemia

- Bohemianism

- Lech, Czech and Rus

References

- ↑ There is no distinction in the Czech language between adjectives referring to Bohemia and to the Czech Republic; i.e. český means both Bohemian and Czech.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05

- ↑ Petr Charvát: "Zrod Českého státu" [Origin of the Bohemian State], March 2007, ISBN: 80-7021-845-2, in Czech

- ↑ http://www.farlang.com/art/bohemian-garnet-jewelry Review article on history of Bohemian Garnets

External links

- Bohemia

- "Bohemia – what did it mean to be Bohemian?" on BBC Radio 4’s In Our Time featuring Norman Davies, Karin Friedrich and Robert Pynsent

|

||||||||