Blackletter

| Latin script (Fraktur variant) | |

| Type | Alphabet |

|---|---|

| Spoken languages | European languages |

| Time period | 12th century – 1946 |

| Parent systems | Latin script → Carolingian minuscule → Latin script (Fraktur variant) |

| Child systems | Fraktur¹, Kurrentschrift, including Sütterlin |

| Unicode range | 1D504–1D537² |

| ISO 15924 | Latf |

|

|

|

|

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

Blackletter, also known as Gothic script or Gothic minuscule, was a script used throughout Western Europe from approximately 1150 to 1500. It continued to be used for the German language until the twentieth century. Fraktur is a notable script of this type, and sometimes the entire group of faces is known as Fraktur. Blackletter is sometimes called Old English, but it is not to be confused with Old English language, despite the popular though mistaken belief that it was written with Blackletter. The Old English (or Anglo-Saxon) language pre-dates Blackletter by many centuries, and was itself written in the insular script.

Contents |

Origins

Carolingian minuscule was the direct ancestor of blackletter. Blackletter developed from Carolingian as an increasingly literate twelfth century Europe required new books in many different subjects. New universities were founded, each producing books for business, law, grammar, history, and other pursuits, not solely religious works for which earlier scripts typically had been used.

These books needed to be produced quickly to keep up with demand. Carolingian, though legible, was time-consuming and labour-intensive to produce. It was large and wide and took up a lot of space on a manuscript in a time when writing materials were very costly. As early as the eleventh century, different forms of Carolingian were already being used, and by the mid-twelfth century, a clearly distinguishable form, able to be written more quickly to meet the demand for new books, was being used in north-eastern France and the Low Countries.

The name Gothic script

The term Gothic was first used to describe this script in fifteenth century Italy, in the midst of the Renaissance, because Renaissance Humanists believed it was a barbaric script. Gothic was a synonym for barbaric. Flavio Biondo, in Italia Illustrata (1531) thought it was invented by the Lombards after their invasion of Italy in the sixth century.

Not only were blackletter forms called Gothic script, but any other seemingly barbarian script, such as Visigothic, Beneventan, and Merovingian, were also labeled "Gothic", in contrast to Carolingian minuscule, a highly legible script which the Humanists called littera antiqua, "the ancient letter", wrongly believing that it was the script used by the Romans. It was invented in the reign of Charlemagne, although only used significantly after that era.

The blackletter must not be confused either with the ancient alphabet of the Gothic language or with the sans-serif typefaces that are also sometimes called Gothic.

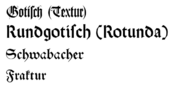

Forms of blackletter

Textualis

Textualis, also known as textura or Gothic bookhand, was the most calligraphic form of blackletter, and today is the form most associated with "Gothic". Johannes Gutenberg carved a textualis typeface – including a large number of ligatures and common abbreviations – when he printed his 42-line Bible. However, the textualis was rarely used for typefaces afterwards.

According to Dutch scholar Gerard Lieftinck, the pinnacle of use for blackletter was the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. For Lieftinck, the highest form of textualis was littera textualis formata, used for de luxe manuscripts. The usual form, simply littera textualis, was used for literary works and university texts. Lieftinck's third form, littera textualis currens, was the cursive form of blackletter, extremely difficult to read and used for textual glosses, and less important books.

Textualis was most widely used in France, the Low Countries, England, and Germany. Some characteristics of the script are:

- tall, narrow letters, as compared to their Carolingian counterparts.

- letters formed by sharp, straight, angular lines, unlike the typically round Carolingian; as a result, there is a high degree of "breaking", i.e. lines that do not necessarily connect with each other, especially in curved letters.

- ascenders (in letters such as b, d, h) are vertical and often end in sharp finials

- when a letter with a bow (in b, d, p, q) is followed by another letter with a bow (such as "be" or "po"), the bows overlap and the letters are joined by a straight line (this is known as "biting").

- a related characteristic is the half r, the shape of r when attached to other letters with bows; only the bow and tail were written, connected to the bow of the previous letter. In other scripts, this only occurred in a ligature with the letter o.

- similarly related is the form of the letter d when followed by a letter with a bow; its ascender is then curved to the left, like the uncial d. Otherwise the ascender is vertical.

- the letters g, j, p, q, y, and the hook of h have descenders, but no other letters are written below the line.

- the letter a has a straight back stroke, and the top loop eventually became closed, somewhat resembling the number 8. The letter s often has a diagonal line connecting its two bows, also somewhat resembling an 8, but the long s is frequently used in the middle of words.

- minims, especially in the later period of the script, do not connect with each other. This makes it very difficult to distinguish i, u, m, and n. A fourteenth century example of the difficulty minims produced is, mimi numinum niuium minimi munium nimium uini muniminum imminui uiui minimum uolunt ("the smallest mimes of the gods of snow do not wish at all in their life that the great duty of the defences of the wine be diminished"). In blackletter this would look like a series of single strokes. Dotted i and the letter j developed because of this. Minims may also have finials of their own.

- the script has many more scribal abbreviations than Carolingian, adding to the speed in which it could be written.

Schwabacher

The Schwabacher was a blackletter form that was much used in early German print typefaces. It continued to be used occasionally until the 20th century. Characteristics of the Schwabacher are:

- The small letter o is rounded on both sides, though at the top and at the bottom, the two strokes join in an angle. Other small letters have analogous forms.

- The small letter g has a horizontal stroke at its top that forms crosses with the two downward strokes.

- The capital letter H has a peculiar form that somewhat reminds the small letter h.

Fraktur

The Fraktur is a form of blackletter that became the most common German blackletter typeface by the mid 16th century. Its use was so common that often any blackletter form is called Fraktur in Germany. Characteristics of the Fraktur are:

- The left side of the small letter o is formed by an angular stroke, the right side by a rounded stroke. At the top and at the bottom, both strokes join in an angle. Other small letters have analogous forms.

- The capital letters are compound of rounded c-shaped or s-shaped strokes.

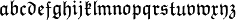

Here is the entire alphabet in Fraktur, using the \mathfrak feature of WikiMedia (see Help: Displaying a formula):

Cursiva

Cursiva refers to a very large variety of forms of blackletter; as with modern cursive writing, there is no real standard form. It developed in the fourteenth century as a simplified form of textualis, with influence from the form of textualis as used for writing charters. Cursiva developed partly because of the introduction of paper, which was smoother than parchment. It was therefore, easier to write quickly on paper in a cursive script.

In cursiva, descenders are more frequent, especially in the letters f and s, and ascenders are curved and looped rather than vertical (seen especially in the letter d). The letters a, g, and s (at the end of a word) are very similar to their Carolingian forms. However, not all of these features are found in every example of cursiva, which makes it difficult to determine whether or not a script may be called cursiva at all.

Lieftinck also divided cursiva into three styles: littera cursiva formata was the most legible and calligraphic style. Littera cursiva textualis (or libraria) was the usual form, used for writing standard books, and it generally was written with a larger pen, leading to larger letters. Littera cursiva currens was used for textbooks and other unimportant books and it had very little standardization in forms.

Hybrida

Hybrida is also called bastarda (especially in France), and as its name suggests, refers to a hybrid form of the script. It is a mixture of textualis and cursiva, developed in the early fifteenth century. From textualis, it borrowed vertical ascenders, while from cursiva, it borrowed long f and ſ, single-looped a, and g with an open descender (similar to Carolingian forms).

Donatus-Kalender (D-K)

The Donatus-Kalender (also known as D-K) is the name for the typeset that Gutenberg used in his first printings. The name is token from the author Aelius Donatus of the Ars grammatica, a scolar book on Latin, and the Kalender (calendar).[1] It is a form of textura.

Blackletter typesetting

While an antiqua typeface is usually compound of roman types and italic types since the 16th century French typographers, the blackletter typefaces never developed a similar distinction. Instead, they use letterspacing (German sperren) for emphasis. When using that method, blackletter ligatures like ch, ck, tz or ſt remain together without additional letterspacing. The use of bold text for emphasis is also alien to blackletter typefaces.

Words from other languages, especially from Romance languages including Latin, are usually typeset in antiqua instead of blackletter. Like that, single antiqua words or phrases may occur within a blackletter text. This does not apply, however, to loanwords that have been incorporated into the language.

National forms

France

Textualis

French textualis was tall and narrow compared to other national forms, and was most fully developed in the late thirteenth century in Paris. In the thirteenth century there also was an extremely small version of textualis used to write miniature Bibles, known as "pearl script." Another form of French textualis in this century was the script developed at the University of Paris, littera parisiensis, which also is small in size and designed to be written quickly, not calligraphically.

Cursiva

French cursiva was used from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century, when it became highly looped, messy, and slanted. Bastarda, the "hybrid" mixture of cursiva and textualis, developed in the fifteenth century and was used for vernacular texts as well as Latin. A more angular form of bastarda was used in Burgundy, the lettre de forme or lettre bourgouignonne, for books of hours such as the Très Riches Heures of John, Duke of Berry.

England

Textualis

English blackletter developed from the form of Caroline minuscule used there after the Norman Conquest, sometimes called "Romanesque minuscule." Textualis forms developed after 1190 and were used most often until approximately 1300, afterward being used mainly for de luxe manuscripts. English forms of blackletter have been studied extensively and may be divided into many categories. Textualis formata ("Old English" or "Black Letter"), textualis prescissa (or textualis sine pedibus, as it generally lacks feet on its minims) , textualis quadrata (or psalterialis) and semi-quadrata, and textualis rotunda are various forms of high-grade formata styles of blackletter.

The University of Oxford borrowed the littera parisiensis in the thirteenth century and early fourteenth century, and the littera oxoniensis form is almost indistinguishable from its Parisian counterpart; however, there are a few differences, such as the round final "s" forms, resembling the number 8, rather than the long "s" used in the final position in the Paris script.

Cursiva

English cursiva began to be used in the thirteenth century, and soon replaced littera oxoniensis as the standard university script. The earliest cursive blackletter form is Anglicana, a very round and looped script, which also had a squarer and angular counterpart, Anglicana formata. The formata form was used until the fifteenth century and also was used to write vernacular texts. An Anglicana bastarda form developed from a mixture of Anglicana and textualis, but by the sixteenth century the principal cursive blackletter used in England was the Secretary script, which originated in Italy and came to England by way of France. Secretary script has a somewhat haphazard appearance, and its forms of the letters a, g, r, and s are unique, unlike any forms in any other English script.

Italy

Rotunda

- Full article at Rotunda (script)

Italian blackletter also is known as rotunda, as it was less angular than in northern centres. The most usual form of Italian rotunda was littera bononiensis, used at the University of Bologna in the thirteenth century. Biting is a common feature in rotunda, but breaking is not.

Italian Rotunda also is characterized by unique abbreviations, such as q with a line beneath the bow signifying "qui", and unusual spellings, such as, x for s ("milex" rather than "miles", and "knight").

Cursiva

Italian cursive developed in the thirteenth century from scripts used by notaries. The more calligraphic form is known as minuscola cancelleresca italiana (or simply cancelleresca, chancery script), which developed into a bookhand, a script used for writing books rather than charters, in the fourteenth century. Cancelleresca influenced the development of bastarda in France and Secretary script in England.

Germany

Despite the frequent association of blackletter with German, the script was actually very slow to develop in German-speaking areas. It developed first in those areas closest to France and then spread to the east and south in the thirteenth century. However, the German-speaking areas are where blackletter remained in use the longest.

Schwabacher typefaces dominated in Germany from about 1480 to 1530, and the style continued in use occasionally until the twentieth century. Most importantly, all of the works of Martin Luther, leading to the Protestant Reformation, as well as the Apocalypse of Albrecht Dürer (1498) used this typeface. Johannes Bämler, a printer from Augsburg, probably first used it as early as 1472. The origins of the name remain unclear; some assume that a typeface-carver from the village of Schwabach—one who worked externally and who thus became known as the Schwabacher—designed the typeface.

Textualis

German Textualis is usually very heavy and angular, and there are few features that are common to all occurrences of the script. One common feature is the use of the letter "w" for Latin "vu" or "uu". Textualis was used in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, afterward becoming more elaborate and decorated and used for liturgical works only.

Johann Gutenberg used a textualis typeface for his famous Gutenberg Bible, possibly the first book ever to be printed with movable type, in 1455. Schwabacher, a blackletter with more rounded letters, soon became the usual printed typeface, but it was replaced by Fraktur in the early seventeenth century.

Fraktur came into use when Emperor Maximilian I (1493–1519) established a series of books and had a new typeface created specifically for this purpose. In the nineteenth century, the use of antiqua alongside Fraktur increased, leading to the Antiqua-Fraktur dispute, which lasted until the Nazis abandoned Fraktur in 1941. Since it was so common, all kinds of blackletter tend to be called Fraktur in German.

This distinctive typeface was a great aid to the Allies in World War II, being particularly easy for forgers to duplicate by hand.

Cursiva

German cursiva is similar to the cursive scripts in other areas, but forms of "a", "s" and other letters are more varied; here too, the letter "w" is often used. A hybrida form, which was basically cursiva with fewer looped letters and with similar square proportions as textualis, was used in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

In the eighteenth century, the pointed quill was adopted for blackletter handwriting. In the early twentieth century, the Sütterlin script was introduced in the schools.

Unicode

Blackletter letters are separately encoded by Unicode in the Mathematical alphanumeric symbols range at U+1D504-1D537 and U+1D56C-1D59F (bold), except for individual letters already encoded in the Letterlike Symbols range (plus long s at U+017F). The reason that Unicode considers these separate characters rather than font variants is the distinctive use of blackletter fonts in mathematics. The character names use “Fraktur” for the alphanumeric symbols but “black-letter” in the “letterlike symbols” range.

- 𝔄 𝔅 ℭ 𝔇 𝔈 𝔉 𝔊 ℌ ℑ 𝔍 𝔎 𝔏 𝔐 𝔑 𝔒 𝔓 𝔔 ℜ 𝔖 𝔗 𝔘 𝔙 𝔚 𝔛 𝔜 ℨ 𝔞 𝔟 𝔠 𝔡 𝔢 𝔣 𝔤 𝔥 𝔦 𝔧 𝔨 𝔩 𝔪 𝔫 𝔬 𝔭 𝔮 𝔯 𝔰 𝔱 𝔲 𝔳 𝔴 𝔵 𝔶 𝔷

- 𝕬 𝕭 𝕮 𝕯 𝕰 𝕱 𝕲 𝕳 𝕴 𝕵 𝕶 𝕷 𝕸 𝕹 𝕺 𝕻 𝕼 𝕽 𝕾 𝕿 𝖀 𝖁 𝖂 𝖃 𝖄 𝖅 𝖆 𝖇 𝖈 𝖉 𝖊 𝖋 𝖌 𝖍 𝖎 𝖏 𝖐 𝖑 𝖒 𝖓 𝖔 𝖕 𝖖 𝖗 𝖘 𝖙 𝖚 𝖛 𝖜 𝖝 𝖞 𝖟

Fonts supporting the range include Code2001.

For normal text writing, the ordinary Latin code points are used. The Blackletter style is then determined by a font with Blackletter glyphs. The glyphs in the SMP should not be used for ordinary text, just for maths. They also lack the Eszett, making them useless for German writing.

See also

References

- ↑ John Man, How One Man Remade the World with Words

Sources

- Bernhard Bischoff, Latin Palaeography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

External links

- Typowiki Article: Blackletter

- Learn Blackletter Online

- ABBYY FineReader XIX Blackletter OCR recognition software

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||