Kazimir Malevich

| Kasimir Malevich | |

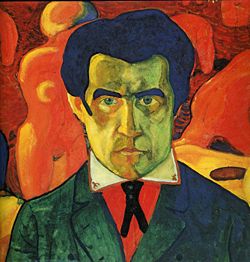

Self-Portrait, 1912 |

|

| Birth name | Kasimir Severinovich Malevich |

| Born | February 23, 1878 Kiev Governorate of Russian Empire |

| Died | May 15, 1935 Leningrad, Soviet Union |

| Field | Painting |

| Training | Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture |

| Movement | Suprematism |

| Works | Black Square, 1915 |

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (Russian: Казимир Северинович Малевич, Polish: Kazimierz Malewicz, Ukrainian Казимир Северинович Малевич [kazɪˈmɪr sɛʋɛˈrɪnoʋɪtʃ mɑˈlɛʋɪtʃ], German: Kasimir Malewitsch), (February 23, 1878 – May 15, 1935) was a painter and art theoretician, pioneer of geometric abstract art and the originator of the Avant-garde Suprematist movement.

Contents |

Life and work

Kazimir Malevich was born near Kiev in the Kiev Governorate of the Russian Empire. His parents, Seweryn and Ludwika Malewicz, were ethnic Belarusians. His father was the manager of a sugar factory. Kazimir was the first of fourteen children, although only nine of the children survived into adulthood. His family moved often and he spent most childhood in the villages of Ukraine amidst sugar-beet plantations, far from centers of culture. Until age 12 he knew nothing of professional artists, though art had surrounded him in childhood. He delighted in peasant embroidery, and in decorated walls and stoves. He himself was able to paint in the peasant style. He studied drawing in Kiev from 1895 to 1896.

In 1904, after the death of his father, he moved to Moscow. He studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1904 to 1910 and in the studio of Fedor Rerberg in Moscow (1904–1910). In 1911 he participated in the second exhibition of the group Soyuz Molodyozhi (Union of Youth) in St. Petersburg, together with Vladimir Tatlin and, in 1912, the group held its third exhibition, which included works by Aleksandra Ekster, Tatlin and others. In the same year he participated in an exhibition by the collective Donkey's Tail in Moscow. By that time his works were influenced by Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Russian avant-garde painters who were particularly interested in Russian folk art called lubok. In March 1913 a major exhibition of Aristarkh Lentulov's paintings opened in Moscow. The effect of this exhibition was comparable with that of Paul Cezanne in Paris in 1907, as all the main Russian avant-garde artists of the time (including Malevich) immediately absorbed the cubist principles and began using them in their works. Already in the same year the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun with Malevich's stage-set became a great success. In 1914 Malevich exhibited his works in the Salon des Independants in Paris together with Alexander Archipenko, Sonia Delaunay, Aleksandra Ekster and Vadim Meller, among others.

It remains one of the great mysteries of 20th century art, how, while leading a comfortable career, during which he just followed all the latest trends in art, in 1915 Malevich suddenly came up with the idea of Suprematism. The fact that Malevich throughout all his life was signing and re-signing his works using earlier dates makes this u-turn in his artistic career even more ambiguous. Be that as it may, in 1915 he published his manifesto From Cubism to Suprematism. In 1915-1916 he worked with other Suprematist artists in a peasant/artisan co-operative in Skoptsi and Verbovka village. In 1916-1917 he participated in exhibitions of the Jack of Diamonds group in Moscow together with Nathan Altman, David Burliuk and A. Ekster, among others. Famous examples of his Suprematist works include Black Square (1915) and White on White (1918).

In 1918 Malevich decorated a play Mystery Bouffe by Vladimir Mayakovskiy produced by Vsevolod Meyerhold.

Malevich also acknowledged that his fascination with aerial photography and aviation led him to abstractions inspired by or derived from aerial landscapes. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: “In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception .... In a series of diagrams illustrating the ‘environments' that influence various painterly styles, the Suprematist is associated with a series of aerial views rendering the familiar landscape into an abstraction..." (excerpted from Ms. Bekman Chadaga's paper delivered at Columbia University's 2000 symposium, "Art, Technology, and Modernity in Russia and Eastern Europe").

After the October Revolution, Malevich became a member of the Collegium on the Arts of Narkompros, the commission for the protection of monuments and the museums commission (all from 1918-1919). He taught at the Vitebsk Practical Art School in the USSR (now part of Belarus) (1919-1922), the Leningrad Academy of Arts (1922-1927), the Kiev State Art Institute (1927-1929), and the House of the Arts in Leningrad (1930). He wrote the book The World as Non-Objectivity (Munich 1926; English trans. 1959) which outlines his Suprematist theories.

In 1927, he traveled to Warsaw and then to Berlin and Munchen for a retrospective which finally brought him international recognition. He arranged to leave most of the paintings behind when he returned to the Soviet Union. Malevich's assumption that a shifting in the attitudes of the Soviet authorities towards the modernist art movement would take place after the death of Lenin and Trotsky's fall from power, were proven correct in a couple of years, when the Stalinist regime turned against formes of abstractism, considering them a type of "bourgeois" art, that could not express social realities. As a consequence, many of his works were confiscated and he was banned from creating and exhibiting similar art.

Critics derided Malevich for reaching art by negating everything good and pure: love of life and love of nature. The Westernizer artist and art historian Alexandre Benois was one such critic. Malevich responded that art can advance and develop for art's sake alone, regardless of its pleasure: art does not need us, and it never needed us since stars first shone in the sky.

Malevich's work only recently reappeared in art exhibitions in Russia after a long absence. Since then art followers have labored to reintroduce the artist to Russian lovers of painting. A book of his theoretical works with an anthology of reminiscences and writings has been published. Many stains on his reputation in Russia remain, however. Recently Ukrainian art followers established the precise birthdate of the artist: February 23, 1879. Malevich and Ukraine, by professor D. Gorbachev, 2006, Kiev, reveals many new biographical details.

Malevich died of cancer in Leningrad on May 15, 1935. On his deathbed he was exhibited with the black square above him. His ashes were sent to Nemchinovka, and buried in a field near his dacha. A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. The city of Leningrad bestowed a pension on Malevich's mother and daughter. "No phenomenon is mortal," Malevich wrote in an unpublished manuscript, "and this means not only the body but the idea as well, a symbol that one is eternally reincarnated in another form which actually exists in the conscious and unconscious person."

Malevich in Popular Culture

- The smuggling of Malevich paintings out of Russia is a key to the plot line of Martin Cruz Smith's thriller Red Square.

- Noah Charney's novel, The Art Thief tells the story of two stolen Malevich White on White paintings, and discusses the implications of Malevich's radical Suprematist compositions on the art world.

Selected works

- 1912 Morning in the Country after Snowstorm

- 1912 The Woodcutter

- 1912-13 Reaper on Red Background

- 1914 The Aviator

- 1914 An Englishman in Moscow

- 1914 Soldier of the First Division

- 1915 Black Square and Red Square

- 1915 Red Square: Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions

- 1915 Suprematist Composition

- 1915 Suprematism (1915)

- 1915 Suprematist Painting: Aeroplane Flying

- 1915 Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions

- 1915-16 Suprematist Painting (Ludwigshafen)

- 1916 Suprematist Painting (1916)

- 1916 Supremus No. 56

- 1916-17 Suprematism (1916-17)

- 1917 Suprematist Painting (1917)

- 1928-32 Complex Presentiment: Half-Figure in a Yellow Shirt

- 1932-34 Running Man

See also

- Lyubov Popova

- Aleksandra Ekster

- El Lissitzky

- UNOVIS

- Suprematism

- Supremus

- IRWIN

- Aerial landscape art

- OBERIU

- ru:Витебский музей современного искусства

References

- The Non-objective World, Kasimir Malevich, trans. Howard Dearstyne, Paul Theobald, 1959. ISBN 0486429741

- Kazimir Malevich and Suprematism 1878-1935, Gilles Néret, Taschen, 2003. ISBN 0874141192

- Dreikausen, Margret, "Aerial Perception: The Earth as Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art" (Associated University Presses: Cranbury, NJ; London, England; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985). ISBN 0-87982-040-3

- Shishanov V.A. Vitebsk Museum of Modern Art: a history of creation and a collection. 1918-1941. - Minsk: Medisont, 2007. - 144 p.[1]

- Kazimir Malevich in the State Russian Museum. Palace Editions. ISBN 978-3930775767. (English Edition)

External links and references

- Guggenheim: Kazimir Malevich

- Feel it... The "Black Square" based on Kazimir Malevich.

- "Black Square"

- "White on White"

- "Malevich on Film"

- DA Collection

- Kazimir Malevich at Olga's Gallery

- "Victory Over the Sun" discussed

- smARThistory: Suprematist Composition: White on White

- Das schwarze quadrat (The Black Square) - Exhibition at Kunsthalle Hamburg

- Lawsuit over ownership of Malevich's Paintings Settled