Black Death

The Black Death, or the Black Plague, was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, widely thought to have been caused by a bacterium named Yersinia pestis (Plague),[1] but recently attributed by some to other diseases.

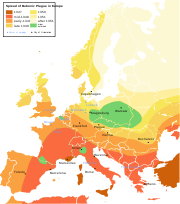

The pandemic is thought to have begun in Central Asia, and spread to Europe during the 1340s.[2][3] The total number of deaths worldwide is estimated at 75 million people,[4] approximately 25–50 million of which occurred in Europe.[5][6] The Black Death is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of Europe's population.[7][8][9] It may have reduced the world's population from an estimated 450 million to between 350 and 375 million in 1400.[10]

The plague is thought to have returned every generation with varying virulence and mortalities until the 1700s.[11] During this period, more than 100 plague epidemics swept across Europe.[12] On its return in 1603, the plague killed 38,000 Londoners.[13] Other notable 17th century outbreaks were the Italian Plague of 1629–1631, and the Great Plague of Seville (1647–1652), the Great Plague of London (1665–1666),[14] and the Great Plague of Vienna (1679). There is some controversy over the identity of the disease, but in its virulent form, after the Great Plague of Marseille in 1720–1722,[15] the Great Plague of 1738 (which hit eastern Europe), and the 1771 plague in Moscow, it seems to have disappeared from Europe in the 19th century.

The 14th century eruption of the Black Death had a drastic effect on Europe's population, irrevocably changing the social structure. It was a serious blow to the Roman Catholic Church, and resulted in widespread persecution of minorities such as Jews, foreigners, beggars, and lepers. The uncertainty of daily survival created a general mood of morbidity, influencing people to "live for the moment", as illustrated by Giovanni Boccaccio in The Decameron (1353).[16]

Contents |

Naming

Medieval people called the 14th century catastrophe either the "Great Pestilence"' or the "Great Plague".[17] Writers contemporary to the plague referred to the event as the "Great Mortality".

The term "Black Death" was introduced for the first time in 1833.[18] It has been popularly thought that the name came from a striking late-stage sign of the disease, in which the sufferer's skin would blacken due to subepidermal hemorrhages (purpura), and the extremities would darken with gangrene (acral necrosis). However, the term is more likely to refer to black in the sense of glum, lugubrious, or dreadful.[19]

The Black Death was, according to chronicles, characterized by buboes (swellings in lymph nodes), like the late 19th century Asian Bubonic plague. Scientists and historians at the beginning of the 20th century assumed that the Black Death was an outbreak of the same disease, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread by fleas with the help of animals like the Black Rat (Rattus rattus). However, this view has recently been questioned by some scientists and historians.[20] New research suggests Black Death is lying dormant.[21]

Plague migration

The plague disease, originally thought to be caused by Yersinia pestis, is enzootic (commonly present) in populations of ground rodents in Central Asia, but it is not entirely clear where the 14th century pandemic started. The popular theory places the first cases in the steppes of Central Asia, although some speculate that it originated around northern India, and others, such as the historian Michael W. Dols, argue that the historical evidence concerning epidemics in the Mediterranean and specifically the Plague of Justinian point to a probability that the Black Death originated in Africa and spread to Central Asia, where it then became entrenched among the rodent population.[22] Nevertheless, from Central Asia it was carried east and west along the Silk Road, by Mongol armies and traders making use of the opportunities of free passage within the Mongol Empire offered by the Pax Mongolica. It was reportedly first introduced to Europe at the trading city of Caffa in the Crimea in 1347. After a protracted siege, during which the Mongol army under Jani Beg was suffering the disease, they catapulted the infected corpses over the city walls to infect the inhabitants. The Genoese traders fled, bringing the plague by ship into Sicily and the south of Europe, whence it spread.[23] Whether or not this hypothesis is accurate, it is clear that several preexisting conditions such as war, famine, and weather contributed to the severity of the Black Death. In China, the thirteenth century Mongol conquest disrupted farming and trading, and led to widespread famine. The population dropped from approximately 120 to 60 million.[24] The 14th century plague is estimated to have killed 1/3 of the population of China.[25]

In Europe, the Medieval Warm Period ended sometime towards the end of the thirteenth century, bringing harsher winters and reduced harvests. In the years 1315 to 1317 a catastrophic famine, known as the Great Famine, struck much of North-West Europe. The famine came about as the result of a large population growth in the previous centuries, with the result that, in the early fourteenth century the population began to exceed the number that could be sustained by productive capacity of the land and farmers.[26]

In Northern Europe, new technological innovations such as the heavy plough and the three-field system were not as effective in clearing new fields for harvest as they were in the Mediterranean because the north had poor, clay-like, soil.[18] Food shortages and skyrocketing prices were a fact of life for as much as a century before the plague. Wheat, oats, hay, and consequently livestock, were all in short supply, and their scarcity resulted in hunger and malnutrition. The result was a mounting human vulnerability to disease, due to weakened immune systems.

The European economy entered a vicious circle in which hunger and chronic, low-level debilitating disease reduced the productivity of labourers, and so the grain output was reduced, causing grain prices to increase. This situation was worsened when landowners and monarchs like Edward III of England (r. 1327–1377) and Philip VI of France (r. 1328–1350), out of a fear that their comparatively high standard of living would decline, raised the fines and rents of their tenants.[27] Standards of living then fell drastically, diets grew more limited, and Europeans as a whole experienced more health problems.

In the autumn of 1314, heavy rains began to fall, which led to several years of cold and wet winters. The already weak harvests of the north suffered and the seven-year famine ensued. The Great Famine was the worst in European history, reducing the population by at least ten percent.[18] Records recreated from dendrochronological studies show a hiatus in building construction during the period, as well as a deterioration in climate.[28]

This was the economic and social situation in which the predictor of the coming disaster, a typhoid (Infected Water) epidemic, emerged. Many thousands died in populated urban centres, most significantly Ypres. In 1318 a pestilence of unknown origin, sometimes identified as anthrax, targeted the animals of Europe, notably sheep and cattle, further reducing the food supply and income of the peasantry.

Causes of the bubonic infection

Several possible causes exist that might have led to the Black Death; the most prevalent is the Bubonic plague theory. Plague and the ecology of Yersinia pestis in soil, and in rodent and (possibly and importantly) human ectoparasites are reviewed and summarized by Michel Drancourt in modeling sporadic, limited, and large plague outbreaks.[30] Modeling of epizootic plague observed in prairie dogs suggests that occasional reservoirs of infection such as an infectious carcass, rather than "blocked fleas" are a better explanation for the observed epizootic behaviour of the disease in nature.[31]

An interesting hypothesis about the epidemiology—the appearance, spread, and especially disappearance—of plague from Europe is that the flea-bearing rodent reservoir of disease was eventually succeeded by another species. The Black Rat (Rattus rattus) was originally introduced from Asia to Europe by trade, but was subsequently displaced and succeeded throughout Europe by the bigger Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus). The brown rat was not as prone to transmit the germ-bearing fleas to humans in large die-offs due to a different rat ecology.[32][33] The dynamic complexities of rat ecology, herd immunity in that reservoir, interaction with human ecology, secondary transmission routes between humans with or without fleas, human herd immunity, and changes in each might explain the eruption, dissemination, and re-eruptions of plague that continued for centuries until its (even more) unexplained disappearance.

Signs and symptoms

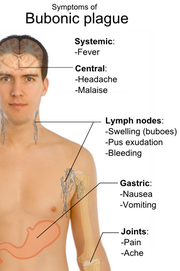

The three forms of plague brought an array of signs and symptoms to those infected. The septicaemic plague is a form of "blood poisoning," and pneumonic plague is an airborne plague that attacks the lungs before the rest of the body. The classic sign of bubonic plague was the appearance of buboes in the groin, the neck, and armpits, which oozed pus and bled. Most victims died within four to seven days after infection. When the plague reached Europe, it first struck port cities and then followed the trade routes, both by sea and land.

The bubonic plague was the most commonly seen form during the Black Death, with a mortality rate of thirty to seventy-five percent and symptoms including fever of 38–41 °C (101–105 °F), headaches, painful aching joints, nausea and vomiting, and a general feeling of malaise. Of those who contracted the bubonic plague, 4 out of 5 died within eight days.[34]

Pneumonic plague was the second most commonly seen form during the Black Death, with a mortality rate of ninety to ninety-five percent. Symptoms included fever, cough, and blood-tinged sputum. As the disease progressed, sputum became free flowing and bright red.

Septicemic plague was the least common of the three forms, with a mortality rate close to one hundred percent. Symptoms were high fevers and purple skin patches (purpura due to DIC).

David Herlihy[35] identifies another potential sign of the plague: freckle-like spots and rashes. Sources from Viterbo, Italy refer to "the signs which are vulgarly called lenticulae", a word which bears resemblance to the Italian word for freckles, lentiggini. These are not the swellings of buboes, but rather "darkish points or pustules which covered large areas of the body".

A Malthusian crisis

In addition, various historians have adopted yet another theory for the cause of the Black Plague, one that points to social, agricultural, and sometimes economic causes. Often known as the Malthusian limit, scholars use this term to express, and/or explain, certain tragedies throughout history. In his 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population, Thomas Malthus asserted that eventually humans would reproduce so greatly that they would go beyond the limits of food supplies; once they reached this point, some sort of "reckoning" was inevitable. While the Black Death may appear to be a "reckoning" of this sort, it was in fact an external, unpredictable factor and does not therefore fit into the Malthusian theory. In his book, The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, David Herlihy explores this idea of plague as an inevitable crisis wrought on humanity in order to control the population and human resources. In the book The Black Death; A Turning Point in History? (ed. William M. Bowsky) he writes “implies that the Black Death’s pivotal role in late medieval society... was now being challenged. Arguing on the basis of a neo-Malthusian economics, revisionist historians recast the Black Death as a necessary and long overdue corrective to an overpopulated Europe.”

Herlihy examines the arguments against the Malthusian crisis, stating “if the Black Death was a response to excessive human numbers it should have arrived several decades earlier” due to the population growth of years before the outbreak of the Black Death. Herlihy also brings up other, biological factors that argue against the plague as a "reckoning" by arguing “the role of famines in affecting population movements is also problematic. The many famines preceding the Black Death, even the ‘great hunger’ of 1314 to 1317, did not result in any appreciable reduction in population levels”. Herlihy concludes the matter stating, “the medieval experience shows us not a Malthusian crisis but a stalemate, in the sense that the community was maintaining at stable levels very large numbers over a lengthy period” and states that the phenomenon should be referred to as more of a deadlock, rather than a crisis, to describe Europe before the epidemics.

Consequences

Figures for the death toll vary widely by area and from source to source as new research and discoveries come to light. It killed an estimated 75–200 million people in the 14th century.[36][37][38] According to medieval historian Philip Daileader in 2007:[39]

The trend of recent research is pointing to a figure more like 45% to 50% of the European population dying during a four-year period. There is a fair amount of geographic variation. In Mediterranean Europe and Italy, the South of France and Spain, where plague ran for about four years consecutively, it was probably closer to 80% to 75% of the population. In Germany and England . . . it was probably closer to 20%.

The best estimate for Middle East — Iraq, Iran, Syria, etc. — is a death rate of a third.[40] The Black Death killed about 40% of Egypt's population.[41]

The governments of Europe had no apparent response to the crisis because no one knew its cause or how it spread. In 1348, the plague spread so rapidly that before any physicians or government authorities had time to reflect upon its origins, about a third of the European population had already perished. In crowded cities, it was not uncommon for as much as fifty percent of the population to die. Europeans living in isolated areas suffered less, and monasteries and priests were especially hard hit since they cared for the Black Death's victims.[42] Because fourteenth century healers were at a loss to explain the cause, Europeans turned to astrological forces, earthquakes, and the poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for the plague's emergence.[18] No one in the fourteenth century considered rat control a way to ward off the plague, and people began to believe only God's anger could produce such horrific displays. There were many attacks against Jewish communities.[43] In August of 1349, the Jewish communities of Mainz and Cologne were exterminated. In February of that same year, Christians murdered two thousand Jews in Strasbourg.[44]

Where government authorities were concerned, most monarchs instituted measures that prohibited exports of foodstuffs, condemned black market speculators, set price controls on grain, and outlawed large-scale fishing. At best, they proved mostly unenforceable, and at worst they contributed to a continent-wide downward spiral. The hardest hit lands, like England, were unable to buy grain abroad: from France because of the prohibition, and from most of the rest of the grain producers because of crop failures from shortage of labour. Any grain that could be shipped was eventually taken by pirates or looters to be sold on the black market. Meanwhile, many of the largest countries, most notably England and Scotland, had been at war, using up much of their treasury and exacerbating inflation. In 1337, on the eve of the first wave of the Black Death, England and France went to war in what would become known as the Hundred Years' War. Malnutrition, poverty, disease and hunger, coupled with war, growing inflation and other economic concerns made Europe in the mid-fourteenth century ripe for tragedy.

As previously mentioned in reference to the plague's sociocultural impacts, renewed religious fervor and fanaticism bloomed in the wake of the Black Death. Some Christians targeted "various groups such as Jews, friars, foreigners, beggars, pilgrims",[45] lepers[46][47] and Roma, thinking that they were to blame for the crisis. Lepers, and other individuals with skin diseases such as acne or psoriasis, were singled out and exterminated throughout Europe. Differences in cultural and lifestyle practices also led to persecution. Because Jews had a religious obligation to be ritually clean they did not use water from public wells and so were suspected of causing the plague by deliberately poisoning the wells. Christian mobs attacked Jewish settlements across Europe; by 1351, sixty major and 150 smaller Jewish communities had been destroyed, and more than 350 separate massacres had occurred.

Recurrence

In England, in the absence of census figures, historians propose a range of pre-incident population figures from as high as 7 million to as low as 4 million in 1300,[48] and a post-incident population figure as low as 2 million.[49] By the end of 1350 the Black Death had subsided, but it never really died out in England over the next few hundred years: there were further outbreaks in 1361–62, 1369, 1379–83, 1389–93, and throughout the first half of the 15th century.[50] The plague often killed 10% of a community in less than a year — in the worst epidemics, such as at Norwich in 1579 and Newcastle in 1636, as many as 30 or 40%. The most general outbreaks in Tudor and Stuart England, all coinciding with years of plague in Germany and the Low Countries, seem to have begun in 1498, 1535, 1543, 1563, 1589, 1603, 1625, and 1636.[51]

The plague repeatedly returned to haunt Europe and the Mediterranean throughout the fourteenth to seventeenth centuries, and although bubonic plague still occurs in isolated cases today, the Great Plague of London in 1665–1666 is generally recognized as one of the last major outbreaks.[52]

In 1466, 40,000 persons died of plague in Paris.[53] In 1570, 200,000 persons died in Moscow and the neighbourhood.[54] The plague of 1575–77 claimed some 50,000 victims in Venice. In 1625, 35,417 Londoners had died of the plague.[55] In 1634, an outbreak of plague killed 15,000 Munich residents.[56] Late outbreaks in central Europe include the Italian Plague of 1629–1631, which is associated with troop movements during the Thirty Years' War, and the Great Plague of Vienna in 1679. About 200,000 people in Moscow died of the disease from 1654 to 1656.[57] The last plague outbreak ravaged Oslo in 1654.[6] In 1656 the plague killed about half of Naples' 300,000 inhabitants.[58] Amsterdam was ravaged in 1663–1664, with a mortality given as 50,000.[59]

A plague epidemic that followed the Great Northern War (1700–1721, Sweden v. Russia and allies) wiped out almost 1/3 of the population in the region.[60] The plague of 1710 killed two-thirds of the inhabitants of Helsinki.[61] An outbreak of plague between 1710 and 1711 claimed a third of Stockholm’s population.[62]

The Black Death ravaged much of the Islamic world.[63] Plague epidemics kept returning to the Islamic world up to the 19th century.[64]

The Third Pandemic started in China in the middle of the 19th century, spreading plague to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone.[65] The plague bacterium could develop drug-resistance and become a major health threat. The ability to resist many of the antibiotics used against plague has been found so far in only a single case of the disease in Madagascar.[66] From 1944 through 1993, 362 cases of human plague were reported in the United States; approximately 90% of these occurred in four western states.[67] Plague was confirmed in the United States from nine western states during 1995.[68]

Black Death in contemporary literature

The Black Death dominated art and literature throughout the generation that experienced it. Much of the most useful manifestations of the Black Death in literature, to historians, comes from the accounts of its chroniclers; contemporary accounts are often the only real way to get a sense of the horror of living through a disaster on such a scale. A few of these chroniclers were famous writers, philosophers and rulers (like Boccaccio and Petrarch). Their writings, however, did not reach the majority of the European population. For example, Petrarch's work was read mainly by wealthy nobles and merchants of Italian city-states. He wrote hundreds of letters and vernacular poetry of great distinction and passed on to later generations a revised interpretation of courtly love.[69] There was, however, one troubadour, writing in the lyric style long out of fashion, who was active in 1348. Peire Lunel de Montech composed the sorrowful sirventes "Meravilhar no·s devo pas las gens" during the height of the plague in Toulouse.

"They died by the hundreds, both day and night, and all were thrown in ... ditches and covered with earth. And as soon as those ditches were filled, more were dug. And I, Agnolo di Tura … buried my five children with my own hands … And so many died that all believed it was the end of the world."

-

-

- - The Plague in Siena: An Italian Chronicle [70]

-

"How many valiant men, how many fair ladies, breakfast with their kinfolk and the same night supped with their ancestors in the next world! The condition of the people was pitiable to behold. They sickened by the thousands daily, and died unattended and without help. Many died in the open street, others dying in their houses, made it known by the stench of their rotting bodies. Consecrated churchyards did not suffice for the burial of the vast multitude of bodies, which were heaped by the hundreds in vast trenches, like goods in a ships hold and covered with a little earth."

-

-

- - Giovanni Boccaccio [71]

-

See also

- Plague of Justinian

- Third Pandemic

- Globalization and disease

- Great Famine of 1315–1317

- Great Plague of London

- Russian plague of 1770-1772

- Abandoned village

- Depopulation

- Eyam a village in England known as the "plague village"

- List of Bubonic plague outbreaks

- Medieval demography

- CCR5-Δ32

- Crisis of the Late Middle Ages

- Hundred Years' War

- Popular revolt in late medieval Europe

- Unit 731

- List of epidemics

- Ring around the rosies (A nursery rhyme believed (probably incorrectly) by many to be connected with Bubonic Plague)

- Hypothetical future disasters

- Flagellant Confraternities (Central Italy)

- Erfurt Treasure

References

- ↑ "Researchers sound the alarm: the multidrug resistance of the plague bacillus could spread". Pasteur.fr. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Molecular insights into the history of plague". Macalester.edu. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Death on a Grand Scale — MedHunters". Medhunters.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Death on the doorstep". Wellcome Trust. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Plague, Plague Information, Black Death Facts, News, Photos — National Geographic". Science.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Øivind Larsen. "DNMS.NO : Michael : 2005 : 03/2005 : Book review: Black Death and hard facts". Dnms.no. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, in L'Histoire n° 310, June 2006, pp.45–46, say "between one-third and two-thirds"; Robert Gottfried (1983). "Black Death" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, volume 2, pp.257–67, says "between 25 and 45 percent".

- ↑ "The Black Death". History.boisestate.edu. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Plague and Public Health in Renaissance Europe". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "International Programs". Census.gov. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Epidemics of the Past: Bubonic Plague — Infoplease.com". Infoplease.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Jo Revill. "Black Death blamed on man, not rats | UK news | The Observer". The Observer. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Plague — LoveToKnow 1911". 1911encyclopedia.org. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "A LIST OF NATIONAL EPIDEMICS OF PLAGUE IN ENGLAND 1348-1665". Urbanrim.org.uk. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Plague History Provence, - by Provence Beyond". Beyond.fr. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Boccaccio: THE DECAMERON , "INTRODUCTION"

- ↑ Judith M. Bennett and C. Warren Hollister, Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006), page 327. ISBN 0072955155. OCLC 56615921.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Ibid.

- ↑ Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, "The Biggest Epidemic of History" (La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire, in L'Histoire n°310, June 2006, pp.38 (article from pp.38 to 49, the whole issue is dedicated to the Black Plague, pp.38–60)

- ↑ Kelly, John (2005). The Great Mortality, An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. HarperCollins Publisher Inc., New York, NY. ISBN 0-06-000692-7. Page 295.

- ↑ Cohn, Samuel K. (2003). The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe. A Hodder Arnold. p. 336. ISBN 0-340-70646-5.

- ↑ Michael W. Dols, "The Second Plague Pandemic and Its Recurrences in the Middle East: 1347–1894" Journal of the Economic Social History of the Orientvol. 22 no. 2 (May 1979), 170–171.

- ↑ "Channel 4 - History — The Black Death". Channel4.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Ping-ti Ho, "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China", in Études Song, Series 1, No 1, (1970) pp. 33–53.

- ↑ "Plague". Center for Health Information Preparedness. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Judith M. Bennett and C. Warren Hollister, Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006), 326. ISBN 0072955155. OCLC 56615921.

- ↑ Ibid., 327.

- ↑ Baillie, Mike (1997). A Slice Through Time. p. p124. ISBN 978–0713476545.

- ↑ "Plague Backgrounder". Avma.org. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ You must specify title = and url = when using {{cite web}}.Drancourt,, M.; Houhamdi, L; Raoult, D.. "". Infectious Diseases. The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70438-8.

- ↑ Webb,, Colleen T.; Christopher P. Brooks, Kenneth L. Gage, and Michael F. Antolin (7 April 2006). "apples Classic flea-borne transmission does not drive plague epizootics in prairie dogs" (PDF). Infectious Diseases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved on 2006-12-12.

- ↑ Appleby, Andrew B. "The Disappearance of the Plague: A Continuing Puzzle", Economic History Review 33, 2 (1980) 161–173

- ↑ Slack, Paul. “The Disappearance of the Plague: An Alternative View.” Economic History Review 34, 3 (1981) 469–476.

- ↑ Rebecca Totaro, Suffering in Paradise: The Bubonic Plague in English Literature from More to Milton, (Pittsburgh: Duquense University Press: 2005), p. 26.

- ↑ Herlihy, The Black Death and the Transformation of the West (1997) Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, p. 29.

- ↑ ABC/Reuters (Tuesday, 29 January 2008). "Black death 'discriminated' between victims (ABC News in Science)", Abc.net.au. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "BBC News | HEALTH | De-coding the Black Death". News.bbc.co.uk (Wednesday, 3 October, 2001, 21:51 GMT 22:51 UK). Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Black Death's Gene Code Cracked". Wired.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Philip Daileader, The Late Middle Ages, audio/video course produced by The Teaching Company, 2007. ISBN 978-1-59803-345-8

- ↑ Q&A with John Kelly on The Great Mortality on National Review Online

- ↑ Egypt - Major Cities, U.S. Library of Congress

- ↑ Judith M. Bennett and C. Warren Hollister, Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006), page 329. ISBN 0072955155. OCLC 56615921.

- ↑ BLACK DEATH, JewishEncyclopedia.com

- ↑ Ibid., 329–330.

- ↑ David Nirenberg, Communities of Violence, op.cit.

- ↑ R.I. Moore The Formation of a Persecuting Society, Oxford, 1987 ISBN 0-631-17145-2

- ↑ David Nirenberg, Communities of Violence, 1998, ISBN 0-691-05889-X

- ↑ The Black Death in Egypt and England: A Comparative Study, Stuart J. Borsch, Austin: University of Texas

- ↑ Secondary sources such as the Cambridge History of Medieval England often contain discussions of methodology in reaching these figures that are necessary reading for anyone wishing to understand this controversial episode in more detail.

- ↑ "BBC — History — Black Death". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "BBC — Radio 4 Voices of the Powerless - 29/08/2002 Plague in Tudor and Stuart Britain". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "The London Plague 1665". Britainexpress.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Plague, 1911 Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ History Magazine - The Black Death

- ↑ Burial of the plague dead in early modern London, Epidemic Disease in London, ed. J.A.I. Champion (Centre for Metropolitan History Working Papers Series, No. 1, 1993)

- ↑ "Texas Department of State Health Services, History of Plague". Dshs.state.tx.us. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Genesis of the Anti-Plague System: The Tsarist Period". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Naples in the 1600s". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Buboni PlagueEuropeFlorence". Mindquestacademy.org. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Kathy McDonough, Empire of Poland". Depts.washington.edu. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Ruttopuisto — Plague Park". Tabblo.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Historical facts about Stockholm, capital of Sweden". Enjoystockholm.com. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Islamic Medicine Part III: Diseases of the Middle Ages

- ↑ The Islamic World to 1600: The Mongol Invasions (The Black Death)

- ↑ INFECTIOUS DISEASES: Plague Through History, sciencemag.org

- ↑ Drug-resistant plague a 'major threat', say scientists, SciDev.Net

- ↑ Human Plague -- United States, 1993-1994, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ↑ An overview of plague in the United States

- ↑ Judith M. Bennett and C. Warren Hollister, Medieval Europe: A Short History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006), page 372. ISBN 0072955155. OCLC 56615921.

- ↑ "plague readings". u.arizona.edu. Retrieved on 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Quotes from the Plague

External links

Media related to Black Death at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Black Death at Wikimedia Commons- Black Death at BBC

|

|||||