Bilirubin

| Bilirubin | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| PubChem | |

| SMILES |

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C33H36N4O6 |

| Molar mass | 584.66214 |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

Bilirubin (formerly referred to as hematoidin) is the yellow breakdown product of normal heme catabolism. Heme is formed from hemoglobin, a principal component of red blood cells. Bilirubin is excreted in bile, and its levels are elevated in certain diseases. It is responsible for the yellow colour of bruises and the yellow discolouration in jaundice.

Contents |

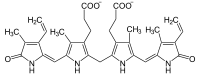

Chemistry

Bilirubin consists of an open chain of four pyrrole-like rings (tetrapyrrole). In heme, by contrast, these four rings are connected into a larger ring, called a porphyrin ring.

Bilirubin is very similar to the pigment phycobilin used by certain algae to capture light energy, and to the pigment phytochrome used by plants to sense light. All of these contain an open chain of four pyrrolic rings.

Like these other pigments, bilirubin changes its conformation when exposed to light. This is used in the phototherapy of jaundiced newborns: the isomer of bilirubin formed upon light exposure is more soluble than the unilluminated isomer.

Several textbooks and research articles show incorrect chemical structures for the two isoforms of bilirubin.[1]

Function

Bilirubin is created by the activity of biliverdin reductase on biliverdin. Bilirubin, when oxidized, reverts to become biliverdin once again. This cycle, in addition to the demonstration of the potent antioxidant activity of bilirubin, has led to the hypothesis that bilirubin's main physiologic role is as a cellular antioxidant.[2][3]

Metabolism

Erythrocytes (red blood cells) generated in the bone marrow are destroyed in the spleen when they get old or damaged. This releases hemoglobin, which is broken down to heme, as the globin parts are turned into amino acids. The heme is then turned into unconjugated bilirubin in the macrophages of the spleen. This unconjugated bilirubin is not water soluble. It is then bound to albumin and sent to the liver.

In the liver it is conjugated with glucuronic acid, making it soluble in water. Much of it goes into the bile and thus out into the small intestine. Some of the conjugated bilirubin remains in the large intestine and is metabolised by colonic bacteria to urobilinogen, which is further metabolized to stercobilinogen, and finally oxidised to stercobilin. This stercobilin gives feces its brown color. Some of the urobilinogen is reabsorbed and excreted in the urine along with an oxidized form, urobilin.

Normally, a tiny amount of bilirubin is excreted in the urine, accounting for the light yellow colour. If the liver’s function is impaired or when biliary drainage is blocked, some of the conjugated bilirubin leaks out of the hepatocytes and appears in the urine, turning it dark amber. The presence of this conjugated bilirubin in the urine can be clinically analyzed, and is reported as an increase in urine bilirubin. However, in the disorder hemolytic anemia, an increased number of red blood cells are broken down, causing an increase in the amount of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood. As stated above, the unconjugated bilirubin is not water soluble, and thus one will not see an increase in bilirubin in the urine. Because there is no problem with the liver or bile systems, this excess unconjugated bilirubin will go through all of the normal processing mechanisms that occur (e.g., conjugation, excretion in bile, metabolism to urobilinogen, reabsorption) and will show up as an increase in urine urobilinogen. This difference between increased urine bilirubin and increased urine urobilinogen helps to distinguish between various disorders in those systems.

Toxicity

Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia in a neonate can lead to accumulation of bilirubin in certain brain regions, a phenomenon known as kernicterus, with consequent irreversible damage to these areas manifesting as various neurological deficits, seizures, abnormal reflexes and eye movements. The neurotoxicity of neonatal hyperbilirubinemia manifests because the blood-brain barrier has yet to develop fully, and bilirubin can freely pass into the brain interstitium, whereas more developed individuals with increased bilirubin in the blood are protected. Aside from specific chronic medical conditions that may lead to hyperbilirubinaemia, neonates in general are at increased risk since they lack the intestinal bacteria that facilitate the breakdown and excretion of conjugated bilirubin in the feces (this is largely why the feces of a neonate are paler than those of an adult). Instead the conjugated bilirubin is converted back into the unconjugated form by the enzyme β-glucuronidase and a large proportion is reabsorbed through the enterohepatic circulation.

Blood tests

Bilirubin is broken down by light, and therefore blood collection tubes (especially serum tubes) should be protected from such exposure.

Bilirubin (in blood) is in one of two forms:

| Abb. | Name(s) | Water Soluble? | Reaction |

| "BC" | "Conjugated" or "Direct bilirubin" |

Yes (bound to glucuronic acid) | Reacts quickly when dyes are added to the blood specimen to produce azobilirubin "Direct bilirubin" |

| "BU" | "Unconjugated" or "Indirect bilirubin" | No | Reacts more slowly. Still produces azobilirubin. Ethanol makes all bilirubin react promptly then calc: Indirect bilirubin = Total bilirubin - Direct bilirubin |

Total bilirubin measures both BU and BC. Total and direct bilirubin levels can be measured from the blood, but indirect bilirubin is calculated from the total and direct bilirubin.

Indirect bilirubin is fat soluble and direct bilirubin is water soluble.

Measurement methods

Originally the Van den Bergh reaction was used for a qualitative estimate of bilirubin.

There are a variety of methods to measure bilirubin.[4]

Total bilirubin is now often measured by the 2,5-dichlorophenyldiazonium (DPD) method, and direct bilirubin is often measured by the method of Jendrassik and Grof.[5]

Blood levels

There are no normal levels of bilirubin as it is an excretion product, and levels found in the body reflects the balance between production and excretion. Different sources provide reference ranges which are similar but not identical. Some examples for adults are provided below (different reference ranges are often used for newborns):

| μmol/L | mg/dL | |

| total bilirubin | 5.1–17.0 [6] | 0.2-1.9,[7] 0.3–1.0,[6] 0.1-1.2[8] |

| direct bilirubin | 1.0–5.1 [6] | 0-0.3,[7] 0.1–0.3,[6] 0.1-0.4[8] |

Mild rises in bilirubin may be caused by:

- Hemolysis or increased breakdown of red blood cells

- Gilbert's syndrome - a genetic disorder of bilirubin metabolism which can result in mild jaundice, found in about 5% of the population

Moderate rise in bilirubin may be caused by:

- Drugs (especially antipsychotic, some sex hormones, and a wide range of other drugs)

- Hepatitis (levels may be moderate or high)

- Chemotherapy

- Biliary stricture (benign or malignant)

Very high levels of bilirubin may be caused by:

- Neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia, where the newborn's liver is not able to properly process the bilirubin causing jaundice

- Unusually large bile duct obstruction, eg stone in common bile duct, tumour obstructing common bile duct etc.

- Severe liver failure with cirrhosis

- Severe hepatitis

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome

- Choledocholithiasis (chronic or acute)

Cirrhosis may cause normal, moderately high or high levels of bilirubin, depending on exact features of the cirrhosis

To further elucidate the causes of jaundice or increased bilirubin, it is usually simpler to look at other liver function tests (especially the enzymes alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase), blood film examination (hemolysis, etc.) or evidence of infective hepatitis (e.g., hpatitis A, B, C, delta, E, etc).

Jaundice

Jaundice may be noticeable in the sclera (white) of the eyes at levels of about 30-50 μmol/l, and in the skin at higher levels.

Jaundice is classified depending upon whether the bilirubin is free or conjugated to glucuronic acid into Conjugated jaundice or Unconjugated jaundice.

See also

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Gilbert's syndrome, a genetic disorder of bilirubin metabolism which can result in mild jaundice, found in about 5% of the population.

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome

- Biliary atresia

- Bilirubin diglucuronide

References

- ↑ "Bilirubin's Chemical Formula". Retrieved on 2007-08-14.

- ↑ Baranano DE, Rao M, Ferris CD, Snyder SH (2002). "Biliverdin reductase: a major physiologic cytoprotectant". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (25): 16093–8. doi:. PMID 12456881.

- ↑ Liu Y, Li P, Lu J, Xiong W, Oger J, Tetzlaff W, Cynader M. (2008). "Bilirubin possesses powerful immunomodulatory activity and suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis". J. Immunol. 181 (3): 1887–97. PMID 18641326.

- ↑ http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=480210 A study of six representative methods of plasma bilirubin analysis. (1961)

- ↑ http://www.clinchem.org/cgi/content/full/47/10/1845 Total Bilirubin Measurement by Photometry on a Blood Gas Analyzer (2001)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Golonka, D et. al.. "Digestive Disorders Health Center: Bilirubin" 3. WebMD. Retrieved on 2008-11-19.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 MedlinePlus Encyclopedia 003468

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Laboratory tests". Retrieved on 2007-08-14.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||