Biblical Magi

- "Three Kings", or "Three Wise Men", redirects here. For other uses, see Three Kings (disambiguation) and Wise men.

In Christian tradition the Magi (Greek: μάγοι, magoi), Three Wise Men, Three Kings or Kings from the East are said to have visited Jesus after his birth, bearing gifts. They are mentioned only in the Gospel of Matthew (Mt 2) , which says that they came "from the east to Jerusalem" to worship the Christ, "born King of the Jews". Because three gifts were recorded, there are traditionally said to have been three Magi, though Matthew does not specify their number.

Contents |

Kings, Wise Men or Magi

The word Magi is a Latinization of the plural of the Greek word magos (μαγος pl. μαγοι). The term is a specific occupational title referring to the priestly caste of Zoroastrianism. As part of their religion, these priests paid particular attention to the stars, and gained an international reputation for astrology, which was at that time a highly regarded science. Their religious practices and use of astrological sciences caused derivatives of the term Magi to be applied to the occult in general and led to the English term magic. Translated in the King James Version as wise men, the same word is given as sorcerer and sorcery when describing "Elymas the sorcerer" in Acts 13:6-11, and Simon Magus, considered a heretic by the early Church, in Acts 8:9-13.

Names

In the Eastern church a variety of different names are given for the three, but in the West the names have been settled since the 8th century as Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar. These derive from an early 6th century Greek manuscript in Alexandria.[2] The Latin text Collectanea et Flores[3] continues the tradition of three kings and their names and gives additional details. This text is said to be from the 8th century, of Irish origin.

In the Eastern churches, Ethiopian Christianity, for instance, has Hor, Karsudan, and Basanater, while the Armenians have Kagpha, Badadakharida and Badadilma.[4][5] None of these names is obviously Persian, although Caspar is also sometimes given as Gaspar or Jasper. One candidate for the origin of the name Caspar appears in the Acts of Thomas as Gondophares (AD 21 – c.AD 47), i.e., Gudapharasa (from which 'Caspar' might derive as corruption of 'Gaspar'). This Gondophares declared independence from the Arsacids to become the first Indo-Parthian king and who was allegedly visited by Thomas the Apostle. Christian legend may have chosen Gondofarr simply because he was an eastern king living in the right time period.

In contrast, the Syrian Christians name the Magi Larvandad, Gushnasaph, and Hormisdas. These names have a far greater likelihood of being originally Persian, though that does not, of course, guarantee their authenticity.

Many Chinese Christians believe that one of the magi came from China.[6]

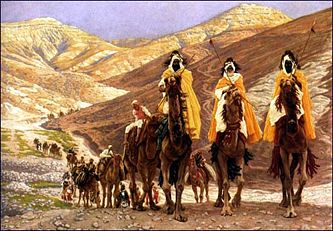

Journey

According to the Gospel of Matthew, the magi found Jesus by following a star; on finding him, they gave him three symbolic gifts: gold, frankincense and myrrh. Warned in a dream that Herod intended to kill the child, they decided to return home by a different route. This prompted Herod to resort to killing all the young children in Bethlehem, an act called the Massacre of the Innocents, in an attempt to eliminate a rival heir to his throne. Jesus and his family had, however, escaped to Egypt beforehand. After these events they passed into obscurity.[7] The story of the nativity in Matthew glorifies Jesus, likens him to Moses, and shows his life as fulfilling prophecy. Some critics consider this nativity story to be an invention of the author of Matthew.[8]

Unlike Luke, the author of Matthew makes no mention of the actual birth of Jesus, focusing instead on what occurred later. Matthew introduces the Magi, who have come to worship Jesus, while accidentally informing Herod of Jesus' existence.

The phrase from the east is the only information Matthew provides on where they came from. Traditionally the view developed that they were Persian or Parthian, a view held for example by John Chrysostom, and Byzantine art generally depicted them in Persian dress. The main support for this is that the first Magi were from Persia and that land still had the largest number of them. Some believe they were from Babylon, which was the centre of Zurvanism, and hence astrology, at the time. Raymond Brown comments that the author of Matthew probably did not have a specific location in mind and the phrase from the east is for literary effect and added exoticism.

After the visit the Magi leave the narrative by returning another way so as to avoid Herod, and do not reappear. Gregory the Great waxed lyrical on this theme, commenting that having come to know Jesus we are forbidden to return by the way we came. There are many traditional stories about what happened to the Magi after this, with one having them baptised by St. Thomas on his way to India. Another has their remains found by Saint Helena and brought to Constantinople, and eventually making their way to Germany and the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral.

Gifts of the Magi

Upon meeting Jesus, the Magi are described as handing over gifts and "falling down" in joyous praise. The use of the term "falling down" more properly means lying prostrate on the ground, which, together with the use of kneeling in Luke's birth narrative, had an important effect on Christian religious practice. Previously both Jewish and Roman tradition had viewed kneeling and prostration as undignified, reserved in Jewish tradition for epiphanies; although for Persians it was a sign of great respect, often showed to the king. But inspired by these verses, kneeling and prostration were adopted in the early Church; while prostration is now very rarely practiced in the West (still being relatively common in the Eastern Churches, especially during Lent), kneeling has remained an important element of Christian worship to this day.

Three of the gifts are explicitly identified in Matthew — gold, frankincense and myrrh; It has been suggested by scholars that the "gifts" were in fact medicinal rather than precious material for tribute.[9][10][11])

This episode can be linked to Isaiah 60 and to Psalm 72 which report gifts being given by kings, and this has played a central role in the perception of the Magi as kings, rather than as astronomer-priests. In a hymn of the late 4th-century hispanic poet Prudentius, the three gifts have already gained their medieval interpretation as prophetic emblems of Jesus' identity, familiar in the carol "We Three Kings" by John Henry Hopkins, Jr., 1857.

Many different theories of the meaning and symbolism of the gifts have been advanced; while gold is fairly obviously explained, frankincense, and particularly myrrh, are much more obscure. They generally break down into two groups:

- That they are all ordinary gifts for a king — myrrh being commonly used as an anointing oil, frankincense as a perfume, and gold as a valuable.

- That they are prophetic — gold as a symbol of kingship on earth, frankincense (an incense) as a symbol of priestship, and myrrh (an embalming oil) as a symbol of death. Sometimes this is described more generally as gold symbolizing virtue, frankincense symbolizing prayer, and myrrh symbolizing suffering.

John Chrysostom suggested that the gifts were fit to be given not just to a king but to God, and contrasted them with the Jews' traditional offerings of sheep and calves, and accordingly Chrysostom asserts that the Magi worshiped Jesus as God. This is believed to be unlikely by some, if the theory that they were members of a Zoroastrian priesthood is correct. However this possibility remains, since zoroastianism prophesied of a messiah type figure Saoshyant who would be born of a virgin — although Saoshyant's virgin birth was not entirely developed until the 9-12th century in the Denkard compendium of beliefs, and prior to that is only hinted at in the older source text, Zam Yasht 19.92[12]. C. S. Mann has advanced the theory that the items were not actually brought as gifts, but were rather the tools of the Magi, who typically would be astrologer-priests. Mann thus sees the giving of these items to Jesus as showing that the Magi were abandoning their practices by relinquishing the necessary tools of their trade, though Brown disagrees with this theory since the portrayal of the Magi had been wholly positive up to this point, with no hint of condemnation.

The gifts themselves have also been criticized as mostly useless to a poor carpenter and his family, and this is often the target of comic satire in television and other comedy. Clarke states that the deist Thomas Woolston once quipped that if they had brought sugar, soap, and candles they would have acted like wise men.[13] What subsequently happened to these gifts is never mentioned in the scripture, but several traditions have developed.[14] One story has the gold being stolen by the two thieves who were later crucified alongside Jesus. Another tale has it being entrusted to and then misappropriated by Judas.

In the Monastery of St. Paul of Mount Athos there is a 15th century golden case containing purportedly the Gift of the Magi. It was donated to the monastery in the 15th century by Mara Branković, daughter of the King of Serbia Đurađ Branković, wife to the Ottoman Sultan Murat II and godmother to Mehmet II the Conqueror (of Constantinople). Apparently they were part of the relics of the Holy Palace of Constantinople and it is claimed they were displayed there since the 4th century AD. After the Athens earthquake of September 9 1999 they were temporarily displayed in Athens in order to strengthen faith and raise money for earthquake victims.

Herod

When the Magi first enquire about Jesus, Matthew says that they are overheard by "Herod the King", which is accepted as referring to Herod the Great who died in 4 BC. This is in contradiction with Luke's mention of the census of Quirinius, which took place in AD 6. The Magi want to pay homage to the King of the Jews, a clear challenge to Herod's authority. Herod was renowned for killing several of his own sons who he felt threatened him. As an Edomite, Herod would be especially threatened by a Davidic heir, who would automatically have a better claim to the throne.

Why all Jerusalem should be troubled by an opponent to Herod is a more important question. Throughout this chapter Matthew shows the leaders of Jerusalem allied with Herod against Jesus, and so these passages have often been quoted in support of Christian anti-Semitism. That all Jerusalem is agitated also seems to conflict with later passages in the same Gospel, where the people are quite oblivious to Jesus' existence. Gundry sees this passage as influenced by the politics of the time it was written, as a foreshadowing of the rejection of Jesus and his church by the leaders of Jerusalem. Brown notes that another option, supported even in ancient times by John Chrysostom, is that Matthew is trying to portray Jesus as a new Moses; in Exodus all Egypt is troubled by Moses, not just the Pharaoh. Levin believes in a third option which sees Matthew as presenting a class war throughout his Gospel, with Jesus on the side of the poor and nomadic, against powerful city dwellers.

Most scholars take the reference to all the chief priests and scribes as referring to the Sanhedrin, however, there is a difficulty in taking this literally as there was only one chief priest at the time, so all the chief priests can only literally refer to a single individual. Taking it less literally, Brown notes that this phrase occurs in other contemporary documents, and refers to the leading priests and former chief priests, not only the current head of the priesthood. A more important difficulty with this passage is its historical implausibility, since records from the period show that Herod and the Sanhedrin were sharply divided, and their relations acrimonious. At the time the priests were largely Sadducees while the scribes were mostly Pharisees, thus both groups being present might be a deliberate attempt to tar both leading Jewish factions as being involved with Herod. Schweizer states that Herod consulting with the Sanhedrin is historically almost inconceivable, and he views their presence in the passage merely as a literary device to have someone able to subsequently quote an Old Testament prophecy.

After having consulted with these religious individuals, Herod is described as secretly meeting with the Magi, and subsequently sending the Magi to Bethlehem to discover where Jesus was so that he could worship him. Many scholars, such as Brown and Schweizer, find this improbable; Bethlehem is only five miles from Jerusalem and it is thus odd that Herod would need to use foreign priests that he had only just met for such an important task, trusting them implicitly despite his usual paranoia, even though he could easily give the task to his soldiers or others he trusted more. R. T. France defends the historicity of this story, theorising that soldiers might alarm the villagers, making it difficult to find the infant, though searching a village only five miles away, even with deeply distrusting villagers, is not so difficult a task when you have an entire army at your disposal. France has also proposed that Herod chose the Magi to carry the task out since they were more likely to be gullible, as foreigners, or at least have less qualms than Jewish soldiers would about killing someone supposedly fitting a Jewish prophecy.

Birthplace

This narrative of the visit of the Magi is the first point in Matthew that Bethlehem, the place of Jesus' birth, is mentioned. That it is specified as being in Judea is ascribed by Albright and Mann to emphasise that it isn't the northern town also named Bethlehem (probably the modern town of Beit Lahna), though other scholars feel the main purpose of its mention is to assert that Jesus was born in the heart of Judaism and not in the unrespected backwater that was Galilee. According to the chronology in Luke, the family left Bethlehem soon after arriving, when Jesus was forty days old, but according to Matthew, the Magi visited Jesus in Bethlehem when he was at a house. This raises the question of how the family has its own home in the town when the Magi visit, having only been able to have a stable when Jesus was born. However, Matthew does not say the house belonged to Joseph and Mary.

Star of Bethlehem

The Magi are described as having followed a star to Bethlehem, which thus traditionally became known as the Star of Bethlehem. Since at least Kepler's time there have been many attempts to link it to an astronomical event, with the most commonly cited being a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 7 BC, fitting in with Matthew's chronology pointing to Jesus being born before 4 BC, and unlike Luke's which points to AD 6. Although traditionally the Magi, coming from the east (apo anatolón, απο ανατολων), are described as having seen a star in the east (ton astera en te anatole, τον αστερα εν τη ανατολη), the Greek word in question is anatole, which many scholars feel more accurately translates as a star rising in the morning, meaning a heliacal rising.[15] The star was just above the horizon but hidden by the brightness of the sun. In the opinion of Konradin Ferrari d'Occhieppo[16] it was not only a triple conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in 7 BC. The star Jupiter (royal star in Babylon) had met Saturn in the sign of Pisces (land in the west) since 854 years.[17]

Astronomer Michael R. Molnar and others have taken the view that Matthew's statements that the star "went before" and "stood over" are terms that refer respectively to the retrogradation and stationing of the royal "wandering star" Jupiter.

John Chrysostom rejected the idea that the Star of Bethlehem was a normal star or similar heavenly body, arguing that it was a more miraculous occurrence, comparable to the pillar of cloud mentioned in Exodus as leading the Israelites out of Egypt. In the Byzantine tradition, influenced by Chrysostom's writing and by palace etiquette, the star was interpreted as a palace official that led the foreign dignitaries to the king, and as such is depicted in Byzantine art.

At the time the notion of new stars as beacons of major events were common, being reported for such figures as Alexander the Great, Mithridates, Abraham, and Augustus. Pliny even takes time to rebut a theory that every person has a star that rises when they are born and fades when they die, evidence that this was believed by some. According to Brown, to many at the time it would have been unthinkable that a Messiah could have been born without some stellar portents beforehand.

Some Christians have had difficulty with reference to the star, since elsewhere in the Bible astrology is condemned. Consequently, R. T. France has argued that the passage is not an endorsement of astrology, but rather an illustration of how God takes care in meeting individuals where they are. Other Christians interpret the star as a fulfilment of the "Star Prophecy" in the Book of Numbers, 24:17:

There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite the corners of Moab, and destroy all the children of Sheth.

The Bethlehem prophecy

The text describes the Magi explaining to Herod about the purpose of their visit by use of a quote from the prophet:

But you, Bethlehem Ephrathah, though you are little among the thousands of Judah, out of you will come for me one who will be ruler over Israel, whose origins are from of old, from ancient times. ― Micah 5:1-3 (according to the Masoretic text)

The quotation given in Matthew differs substantially from both the Septuagint and Masoretic texts of the same passage. The Septuagint and Masoretic refer to Bethlehem as Bethlehem Ephratah, which Matthew alters to Bethlehem, land of Judah, apparently to further emphasise that Jesus was born in Judea not Galilee, where he spent much of his ministry, an area that was viewed by most religious Jews as being unclean and lower than the half-cast people in the intermediate region. An even more important change is the almost total inversion of the meaning — Micah has you are little among the thousands of Judah whereas Matthew's quote of it has you are not least among the princes of Judah.

Matthew also replaces the word ruler with shepherd, apparently to present the argument that a Messiah would be a religious figure rather than a political one. The portion of Micah where this quote is found is clearly discussing a Messiah and states that like King David, the Messiah would originate from Bethlehem. At the time it was not widely accepted that the Messiah would necessarily be born in Bethlehem, just that his ancestors would have been, and thus it was not considered essential for a Messiah to be someone born in that town, although it was considered a reasonable area for one to happen to originate from: certainly far more reasonable than the peripheral area of Galilee where Jesus grew up.

Tombs

Marco Polo claimed that he was shown the three tombs of the Magi at Saveh south of Tehran in the 1270s:

In Persia is the city of Saba, from which the Three Magi set out and in this city they are buried, in three very large and beautiful monuments, side by side. And above them there is a square building, beautifully kept. The bodies are still entire, with hair and beard remaining.[18]

A Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne Cathedral, according to tradition, contains the bones of the Three Wise Men. Reputedly they were first discovered by Saint Helena on her famous pilgrimage to Palestine and the Holy Lands. She took the remains to the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople; they were later moved to Milan (some sources say by the city's bishop, Eustorgius I[19]), before being sent to their current resting place by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I in AD 1164. The Milanese celebrate their part in the tradition by holding a medieval costume parade every 6 January.

A version of the detailed elaboration familiar to us is laid out by the 14th century cleric John of Hildesheim's Historia Trium Regum ("History of the Three Kings"). In accounting for the presence in Cologne of their mummified relics, he begins with the journey of Helena, mother of Constantine I to Jerusalem, where she recovered the True Cross and other relics:

Queen Helen… began to think greatly of the bodies of these three kings, and she arrayed herself, and accompanied by many attendants, went into the Land of Ind… after she had found the bodies of Melchior, Balthazar, and Gaspar, Queen Helen put them into one chest and ornamented it with great riches, and she brought them into Constantinople… and laid them in a church that is called Saint Sophia.

Religious significance

According to most forms of Christianity, the Magi were the first religious figures to worship Christ, and for this reason the story of the Magi is particularly respected and popular among many Christians. The visit of the Magi is commemorated by Catholics and other Christian churches (but not the Eastern Orthodox) on the observance of Epiphany, January 6. The Eastern Orthodox celebrate it on December 25. This visit is frequently treated in Christian art and literature as The Adoration of the Magi.

Upon this kernel of information Christians embroidered many circumstantial details about the Magi. One of the most important changes was their rising from astrologers to kings. The general view is that this is linked to Old Testament prophesies that have the Messiah being worshipped by kings in Isaiah 60:3, Psalm 72:10, and Psalm 68:29. Early readers reinterpreted Matthew in light of these prophecies and elevated the Magi to kings. Mark Allan Powell rejects this view. He argues that the idea of the Magi as kings arose considerably later in the time after Constantine and the change was made to endorse the role of Christian monarchs. By AD 500 all commentators adopted the prevalent tradition of the three were kings, and this continued until the Protestant Reformation.

Though the Qur'an omits Matthew's episode of the Magi, it was well known in Arabia. The Muslim encyclopaedist al-Tabari, writing in the 9th century, gives the familiar symbolism of the gifts of the Magi. Al-Tabari gave his source for the information to be the later 7th century writer Wahb ibn Munabbih.[20]

This positive interpretation of the Magi is not unopposed. The Jehovah's Witnesses[21] do not see the arrival of the Magi as something to be celebrated, but instead stress the Biblical condemnation of sorcery and astrology in such texts as Deuteronomy 18:10–11, Leviticus 19:26, and Isaiah 47:13–14. They also point to the fact that the star seen by the Magi led them first to a hostile enemy of Jesus, Herod, and only then to the child's location — the argument being that if this was an event from God, it makes no sense for them to be led to a ruler with intentions to kill the child before taking them to Jesus.

Traditions of the Epiphany

- Holidays celebrating the arrival of the Magi traditionally recognise a sharp distinction between the date of their arrival and the date of Jesus' birth. Matthew's introduction of the Magi gives the reader no reason to believe that they were present on the night of the birth, instead stating that they arrived at some point after Jesus had been born, and the Magi are described as leading Herod to assume that Jesus is up to one year old.

- Christianity celebrates the Magi on the day of Epiphany, January 6, the last of the twelve days of Christmas, particularly in the Spanish-speaking parts of the world. In these Spanish-speaking areas, the three kings (Sp. "los Reyes Magos de Oriente", also "Los Tres Reyes Magos") receive wish letters from children and magically bring them gifts on the night before Epiphany. According to the tradition, the Magi come from the Orient on their camels to visit the houses of all the children; much like Santa Claus with his reindeer, they visit everyone in one night. In some areas, children prepare a drink for each of the Magi, it is also traditional to prepare food and drink for the camels, because this is the only night of the year when they eat.

- Spanish cities organize cabalgatas in the evening, in which the kings and their servants parade and throw sweets to the children (and parents) in attendance. The cavalcade of the three kings in Alcoi claims to be the oldest in the world; the participants who portray the kings and pages walk through the crowd, giving presents to the children directly.

- A tradition in most of Central Europe involves writing the initials of the three kings' names above the main door of the home to confer blessings on the occupants for the New Year. For example, 20 + C + M + B + 08. The initials may also represent "Christus mansionem benedicat" (Christ bless this house). In Catholic parts of Germany and in Austria, this is done by so called Sternsinger (star singers), children, dressed up as the Magi, carrying the star. In "exchange" for writing the initials, they collect money for charity projects in the third world.

- In France and Belgium, the holiday is celebrated with a special tradition: within a family, a cake is baked which contains one single bean. Whoever gets the bean is "crowned" king for the remainder of the holiday.

- This tradition also exists in Spain, but with one small variant; the cake, in this case actually a ring-shaped pastry or Roscón de Reyes, is most commonly bought, not baked, and it contains a small figurine of a Baby Jesus and a dry broad bean. The one who gets the figurine is crowned, but whoever gets the bean has to pay the value of the cake to the person that originally bought it.

- In Mexico they have the same ring-shaped cake Rosca de Reyes, it contains figurines of the Baby Jesus. Whoever gets a figurine is supposed to buy tamales for the Candelaria feast on February the second.

- In New Orleans, Louisiana and surrounding regions, a similar ring-shaped cake known as a "king cake" traditionally becomes available in bakeries from the Epiphany through Mardi Gras. The Baby Jesus is represented by a small, plastic doll in the cake. The different varieties of pastry involved is large. However, due to recent encroachment of commercialism and liability concerns, king cakes may be available year round and the plastic doll is not hidden in the cake, but just included in the packaging.

Adoration of the Magi in art

The Magi most frequently appear in European art in the Adoration of the Magi; less often The Journey of the Magi has been a popular topos, and other scenes such as the Magi before Herod and the Dream of the Magi also appear in the Middle Ages. In Byzantine art they are depicted as Persians, wearing trousers and phrygian caps. Crown appear from the 10th century. Medieval artists also allegorised the theme to represent the three ages of man. Beginning in the 12th century, and very often by the 15th, the Kings also represent the three parts of the known (pre-Columban) world in Western art, especially in Northern Europe. Balthasar is thus represented as a young African or Moor and Caspar may be depicted with distinctive Oriental features.

An early Anglo-Saxon picture survives on the Franks Casket, probably a non-Christian king’s hoard-box (early 7th century, whalebone carving); or rather the hoard-box survived Christian attacks on non-Christian art and sculpture because of that picture.[22] In its composition it follows the oriental style, which renders a courtly scene, with the Virgin and Christ facing the spectator, while the Magi devoutly approach from the (left) side. Even amongst non-Christians who had heard of the Christian story of the Magi, the motif was quite popular, since the Magi had endured a long journey and were generous. Instead of an angel, the picture places a swan, interpretable as the hero's fylgja (a protecting spirit, and shapeshifter).

In Austrian artist Gottfried Helnwein's painting Epiphany I (Adoration of the Magi) (1996), Nazi officers in uniform cluster around an Aryan woman, an icy blonde Madonna. The Christ toddler, who stands on Mary's lap, stares defiantly out of the canvas. Helnwein's baby Jesus resembles Adolf Hitler [23].

More generally they appear in popular Nativity scenes and other Christmas decorations that have their origins in the Neapolitan variety of the Italian presepio or Nativity crèche.

Representation in other art forms

The Magi are featured in Menotti's opera Amahl and the Night Visitors, and in several Christmas carols, of which the best-known English one is "We Three Kings".

In the film Donovan's Reef, a Christmas play is held in French Polynesia. However, instead of the traditional correspondence of Magi to continents, the version for Polynesian Catholics features the king of Polynesia, the king of America, and the king of China.

Further sentimental narrative detail was added in the novel and movie Ben-Hur, where Balthasar appears as an old man, who goes back to Palestine to see the former child Jesus become an adult.

According to Howard Clarke, in the United States, Christmas cards featuring the Magi outsell those with shepherds.

T. S. Eliot's poem The Journey of the Magi (1927) re-tells the story with a foreshadowing of the crucifixion, as does the poem Visit of the Wise Men by Timothy Dudley-Smith.[24]

In Michael Ende's children books Jim Button and Luke the Engine Driver and Jim Button and the Wild 13, one of the Three Kings plays a major role in one of the main character's background.

Salley Vickers's Miss Garnet's Angel links the Epiphany story, and arrival of the Magi, with the ancient Zoroastrian elements in the Apocryphal Book Of Tobit.

See also

- List of names for the Biblical nameless

- Astrology

- History of astrology

- Christianity and astrology

- Zoroastrian

- Saint Nicholas

- Magi

- Simon Magus

References and notes

- Citations

- ↑ Geza Vermes, The Nativity: History and Legend, London, Penguin, 2006, p22;E. P. Sanders describes the nativity stories as "the clearest cases of invention in the Gospels". E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, 1993, p.85

- ↑ Translated into the Latin Excerpta Latina Barbari: At that time in the reign of Augustus, on 1st January the Magi brought him gifts and worshipped him. The names of the Magi were Bithisarea, Melichior and Gathaspa. (Excerpta Latina Barbari, page 51B). The little chronicle was probably composed in Greek in about 500 A.D.)

- ↑ Kehrer, Hugo, Die Heiligen Drei Könige in Literatur und Kunst, Band I, 1908, 1976², p. 66, an old Greek document translated into Latin: Melchior was an old man with a white beard, Caspar a boy without beard, and whereas the third man, Balthasar, had a dark full beard. Latin original: Magi sunt qui munera Domino dederunt: primus fuisse dicitur Melchior, senex et canus, barba prolixa et capillis, tunica hyacinthina, sagoque mileno, et calceamentis hyacinthino et albo mixto opere, pro mitrario variae compositionis indutus: aurum obtulit regi Domino (Melchior gave gold). Secundum, nomine Caspar, juvenis imberbis, rubicundus, mylenica tunica, sago rubeo, calceamentis hyacinthinis vestitus: thure quasi Deo oblatione digna, Deum honorabat (Caspar gave frankincense). Tertius, fuscus, integre barbatus, Balthasar nomine, habens tunicam rubeam, albo vario, calceamentis inimicis amicus: per myrrham filium hominis moriturum professus est (Balthasar gave myrhh). Omnia autem vestimenta eorum Syriaca (clothes coming from Syria) sunt. (Collectanea et Flores), in: Patrologia Latina, XCIV, page 541(D)

- ↑ Acta Sanctorum, May, I, 1780.

- ↑ Concerning The Magi And Their Names.

- ↑ Hattaway, Paul; Brother Yun; Yongze, Peter Xu; and Wang, Enoch. Back to Jerusalem. (Authentic Publishing, 2003). retrieved May 2007

- ↑ Eliza Marian Butler, "The Myth of the Magus By Eliza Marian Butler". Cambridge University, 1993. 281 pages. Page 20. ISBN 0521437776

- ↑ J. Duncan M. Derrett, "Further light on the narratives of the Nativity". Novum Testamentum 17.2 (April 1975), pp. 81-108: "Jean Danielou's conclusion that the Magi were an invention of Matthew"

- ↑ Page, Sophie,"Magic In Medieval Manuscripts". University of Toronto Press, 2004. 64 pages. ISBN 0802037976Page 18.

- ↑ Gustav-Adolf Schoener and Shane Denson [Translator], "Astrology: Between Religion and the Empirical".

- ↑ "Frankincense: festive pharmacognosy". Pharmaceutical journal. Vol 271, 2003. pharmj.com.

- ↑ AVESTA: KHORDA AVESTA (English): Zamyad Yasht ('Hymn to the Earth')

- ↑ Clarke, Howard W. The Gospel of Matthew and its Readers: A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel.

- ↑ Lambert, John Chisholm, in James Hastings (ed.) "A Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels". Page 100.

- ↑ d’Occhieppo, Konradin Ferrari, Neue Argumente zu Aufgang und Stillstand des Sterns in der Magierperikope Matthäus 2, 1–12, in Sitzungsber. Abt. I I (1997) 206: 317–44. Vienna: 1998.

- ↑ Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften ÖAW.SmnII/173, Wien 1965, pp. 343–76, in: d’Occhieppo, Der Stern von Bethlehem in astronomischer Sicht, 1994, p. 7.

- ↑ http://wwwapp.bmbwk.gv.at/kalender/1224/augen1224d.html and a photo (Jupiter and Saturn are left)

- ↑ Polo, Marco, The Book of the Million, book i.

- ↑ Sant' Eustorgio I di Milano

- ↑ We, three kings of Orient were.

- ↑ http://www.watchtower.org/library/w/2000/12/15/article_01.htm

- ↑ Franks Casket.

- ↑ Denver Art Museum, Radar, Selections from the Collection of Vicki and Kent Logan, Gwen F. Chanzit, 2006 [1]

- ↑ Dudley-Smith, Timothy (1984). Lift Every Heart: Collected hymns 1961-1983 and some early poems. Collins. ISBN 0-00-599797-6.

- General references

- Albright, W. F. and C. S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971.

- Alfred Becker: “Franks Casket. Zu den Bildern und Inschriften des Runenkästchens von Auzon (Regensburg, 1973) pp. 125–142, Ikonographie der Magierbilder, Inschriften.

- Brown, Raymond E. The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in Matthew and Luke. London: G. Chapman, 1977.

- Clarke, Howard W. The Gospel of Matthew and its Readers: A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel. Bloomington.

- Chrysostom, John "Homilies on Matthew: Homily VI". circa fourth century.

- France, R. T. The Gospel According to Matthew: an Introduction and Commentary. Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1985.

- Gundry, Robert H. Matthew a Commentary on his Literary and Theological Art. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1982.

- Benecke, P. V. M. (1900). "Magi". A Dictionary of the Bible III. Ed. James Hastings. pages 203-206.

- Hill, David. The Gospel of Matthew. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981

- Lambert, John Chisholm, A Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels. Page 97 - 101.

- Levine, Amy-Jill. "Matthew." Women's Bible Commentary. Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1998.

- Molnar, Michael R., The Star of Bethlehem: The Legacy of the Magi. Rutgers University Press, 1999. 187 pages. ISBN 0813527015

- Powell, Mark Allan. "The Magi as Wise Men: Re-examining a Basic Supposition." New Testament Studies. Vol. 46, 2000.

- Schweizer, Eduard. The Good News According to Matthew. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1975.

- Watson, Richard, A Biblical and Theological Dictionary Page 608 - 611.

External links

- Mark Rose, "The Three Kings & the Star": the Cologne reliquary and the BBC popular documentary

- John of Hildesheim, "History of the three Kings" modernized in English by H. S. Morris

- Alfred Becker, Franks Casket

- Caroline Stone, "We Three Kings of Orient Were"

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Magi

|

Life of Jesus: The Nativity |

||

|

Star of Bethlehem |

Events |

Flight into Egypt |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||