Benoît Mandelbrot

| Benoît Mandelbrot | |

Mandelbrot in 2007

|

|

| Born | 20 November 1924 Warsaw, Poland |

|---|---|

| Residence | France; United States |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | Mathematician |

| Institutions | Yale University International Business Machines (IBM) Pacific Northwest National Laboratory |

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique California Institute of Technology University of Paris |

| Doctoral students | F. Kenton Musgrave Eugene F. Fama among others |

| Known for | Mandelbrot set |

| Notable awards | Wolf Prize (1993) Japan Prize (2003) |

Benoît B. Mandelbrot[1] (born 20 November 1924) is a French mathematician, best known as the father of fractal geometry. He is Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences, Emeritus at Yale University; IBM Fellow Emeritus at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center; and Battelle Fellow at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. He was born in Poland, but his family moved to France when he was a child; he is a dual French and American citizen and was educated in France. Mandelbrot now lives and works in the United States.

Contents |

Early years

Mandelbrot was born in Warsaw in a Jewish family from Lithuania. Anticipating the threat posed by Nazi Germany, the family fled from Poland to France in 1936 when he was 11. He remained in France through the war to near the end of his college studies. He was born into a family with a strong academic tradition—his mother was a medical doctor and he was introduced to mathematics by two uncles. His uncle, Szolem Mandelbrojt, was a Parisian mathematician. His father, however, made his living trading clothing.[2]

Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rolin in Paris until the start of World War II, when his family moved to Tulle. He was helped by Rabbi David Feuerwerker, the Rabbi of Brive-la-Gaillarde, to continue his studies. In 1944 he returned to Paris. He studied at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon and in 1945-47 attended the École Polytechnique, where he studied under Gaston Julia and Paul Lévy. From 1947 to 1949 he studied at California Institute of Technology where he studied aeronautics. Back in France, he obtained a Ph.D. in Mathematical Sciences at the University of Paris in 1952.[2]

From 1949 to 1957 Mandelbrot was a staff member at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. During this time he spent a year at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey where he was sponsored by John von Neumann. In 1955 he married Aliette Kagan and moved to Geneva, Switzerland then Lille, France.[3]

In 1958 the couple moved to the United States where Mandelbrot joined the research staff at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York.[3] He remained at IBM for thirty-two years, becoming an IBM Fellow, and later Fellow Emeritus.[2]

Later years

From 1951 onward, Mandelbrot worked on problems and published papers not only in mathematics but in applied fields such as information theory, economics, and fluid dynamics. He became convinced that two key themes, fat tails and self-similar structure, ran through a multitude of problems encountered in those fields.

Mandelbrot found that price changes in financial markets did not follow a Gaussian distribution, but rather Lévy stable distributions having theoretically infinite variance. He found, for example, that cotton prices followed a Lévy stable distribution with parameter α equal to 1.7 rather than 2 as in a Gaussian distribution. "Stable" distributions have the property that the sum of many instances of a random variable follows the same distribution but with a larger scale parameter.[4]

Mandelbrot also put his ideas to work in cosmology. He offered in 1974 a new explanation of Olbers' Paradox (the "dark night sky" riddle), demonstrating the consequences of fractal theory as a sufficient, but not necessary, resolution of the paradox. He postulated that if the stars in the universe were fractally distributed (for example, like Cantor dust), it would not be necessary to rely on the Big Bang theory to explain the paradox. His model would not rule out a Big Bang, but would allow for a dark sky even if the Big Bang had not occurred.

In 1975, Mandelbrot coined the term fractal to describe these structures, and published his ideas in Les objets fractals, forme, hasard et dimension (1975; an English translation Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension was published in 1977).[5]

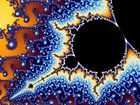

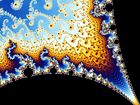

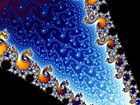

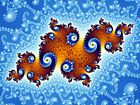

While on secondment as Visiting Professor of Mathematics at Harvard University in 1979, Mandelbrot began to study fractals called Julia sets that were invariant under certain transformations of the complex plane. Building on previous work by Gaston Julia and Pierre Fatou, Mandelbrot used a computer to plot images of the Julia sets of the formula z² − μ. While investigating how the topology of these Julia sets depended on the complex parameter μ he studied the Mandelbrot set fractal that is now named after him. (Note that the Mandelbrot set is now usually defined in terms of the formula z² + c, so Mandelbrot's early plots in terms of the earlier parameter μ are left–right mirror images of more recent plots in terms of the parameter c.)

In 1982, Mandelbrot expanded and updated his ideas in The Fractal Geometry of Nature.[6] This influential work brought fractals into the mainstream of professional and popular mathematics.

Upon his retirement from IBM in 1987, Mandelbrot joined the Yale Department of Mathematics. At the time of his retirement in 2005, he was Sterling Professor of Mathematical Sciences. His awards include the Wolf Prize for Physics in 1993, the Lewis Fry Richardson Prize of the European Geophysical Society in 2000, the Japan Prize in 2003, and the Einstein Lectureship of the American Mathematical Society in 2006. The small planet 27500 Mandelbrot was named in his honor. In November 1990, he was made a Knight in the French Legion of Honour. In December 2005, Mandelbrot was appointed to the position of Battelle Fellow at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.[7] Mandelbrot was promoted to Officer of the French Legion of Honour in January 2006.[8]

Fractals and regular roughness

Although Mandelbrot coined the term fractal, some of the mathematical objects he presented in The Fractal Geometry of Nature had been described by other mathematicians. Before Mandelbrot, they had been regarded as isolated curiosities with unnatural and non-intuitive properties. Mandelbrot brought these objects together for the first time and turned them into essential tools for the long-stalled effort to extend the scope of science to non-smooth objects in the real world. He highlighted their common properties, such as self-similarity (linear, non-linear, or statistical), scale invariance, and a (usually) non-integer Hausdorff dimension.

He also emphasized the use of fractals as realistic and useful models of many "rough" phenomena in the real world. Natural fractals include the shapes of mountains, coastlines and river basins; the structures of plants, blood vessels and lungs; the clustering of galaxies; and Brownian motion. Fractals are found in human pursuits, such as music, painting, architecture, and stock market prices. Mandelbrot believed that fractals, far from being unnatural, were in many ways more intuitive and natural than the artificially smooth objects of traditional Euclidean geometry:

Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles, and bark is not smooth, nor does lightning travel in a straight line.

—Mandelbrot, in his introduction to The Fractal Geometry of Nature

Mandelbrot has been called a visionary.[9] His informal and passionate style of writing and his emphasis on visual and geometric intuition (supported by the inclusion of numerous illustrations) made The Fractal Geometry of Nature accessible to non-specialists. The book sparked widespread popular interest in fractals and contributed to chaos theory and other fields of science and mathematics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Honors and Awards

A partial list of awards received by Mandelbrot:[10]

|

|

|

See also

- " How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension", a 1967 paper by Mandelbrot

- Mandelbrot Competition

- skewness risk, kurtosis risk

Notes and references

- ↑ Benoît is read as "ben-wa" [bənwa]. The pronunciation of the name "Mandelbrot", which is a Yiddish and German word meaning "almond bread", is given variously in dictionaries. The Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary and the Longman Pronouncing Dictionary give [ˈmæn.dəlˌbɹoʊt] (first syllable sounds like "man"; last syllable rhymes with "boat"); the Bollard Pronouncing Dictionary of Proper Names gives the quasi-French pronunciation [ˈmæn.dəlˌbɹɔː] (last syllable rhymes with "draw"); the American Heritage Dictionary gives [ˈmɑːn.dəlˌbɹɑt] (first syllable has the vowel sound of the 'a' in "father"; last syllable rhymes with "pot"). Mandelbrot himself, as most Frenchmen do, pronounces his name as [mɑ̃dɛlbʁot] (roughly maw-dell-brote) when speaking in French. (Source: recording of the September 11, 2006, ceremony at which Mandelbrot received the Officer of the Legion of honour insignia.)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Mandelbrot, Benoit (2002), "A maverick's apprenticeship", The Wolf Prizes for Physics, Imperial College Press, http://www.math.yale.edu/mandelbrot/web_pdfs/mavericksApprenticeship.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Barcellos, Anthony (1984), "Interview Of B. B. Mandelbrot", Mathematical People, Birkhaüser, http://www.math.yale.edu/mandelbrot/web_pdfs/inHisOwnWords.pdf

- ↑ New Scientist, 19 April 1997

- ↑ Fractals: Form, Chance and Dimension, by Benoît Mandelbrot; W H Freeman and Co, 1977; ISBN 0716704730

- ↑ The Fractal Geometry of Nature, by Benoît Mandelbrot; W H Freeman & Co, 1982; ISBN 0716711869

- ↑ PNNL press release: Mandelbrot joins Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

- ↑ Légion d'honneur announcement of promotion of Mandelbrot to officier

- ↑ Devaney, Robert L. (2004). ""Mandelbrot’s Vision for Mathematics" in Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics. Volume 72.1". American Mathematical Society. Retrieved on 2007-01-05.

- ↑ Mandelbrot, Benoit B. (2 February 2006). "Vita and Publications (Word document)". Retrieved on 2007-01-06.

Further reading

- The (Mis)Behavior of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin, and Reward, by Benoît Mandelbrot and Richard L. Hudson; Basic Books, 2004; ISBN 0-465-04355-0

- A focus on the exceptions that prove the rule, by Benoît Mandelbrot and Nassim Taleb; Financial Times, 23 March 2006.

- Heinz-Otto Peitgen, Hartmut Jürgens, Dietmar Saupe and Cornelia Zahlten: Fractals: An Animated Discussion (63 min video film, interviews with Benoît Mandelbrot and Edward Lorenz, computer animations), W.H. Freeman and Company, 1990. ISBN 0-716-72213-5 (re-published by Films for the Humanities & Sciences, ISBN 978-0-7365-0520-8)

External links

- Mandelbrot's page at Yale

- Yale Economic Review - Review of The (mis)Behavior of Markets

- Interview of the École Polytechnique site

- Biography of Mandelbrot

- Video stream of Mandelbrot lecturing at MIT

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Benoît Mandelbrot", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- Benoît Mandelbrot at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Benoît Mandelbrot video at the Peoples Archive

|

||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Mandelbrot, Benoît |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Mathematician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 20 November 1924 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Warsaw, Poland |

| DATE OF DEATH | |

| PLACE OF DEATH | |