Benedict of Nursia

- "Saint Benedict" redirects here. This article is about the founder of Western monasticism; for other saints named Benedict, see Benedict.

| Saint Benedict | |

|---|---|

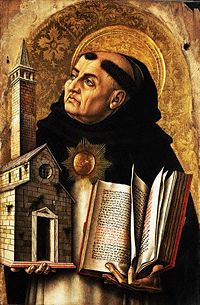

Detail from fresco by Fra Angelico |

|

| Abbot Patron of Europe |

|

| Born | c. 480, Norcia (Umbria, Italy) |

| Died | c. 547, Monte Cassino |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Communion Eastern Orthodox Church Lutheran Church |

| Canonized | 1220 |

| Major shrine | Monte Cassino Abbey, with his burial Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire, near Orléans, France |

| Feast | Western Christianity: 11 July (in pre-1969 calendars, 21 March) Byzantine Rite: 14 March |

| Attributes | -Bell -Broken cup -Broken cup and serpent representing poison -Broken utensil -Bush -Crosier -Man in a Benedictine cowl holding Benedict's rule or a rod of discipline -Raven |

| Patronage | -Against poison -Against witchcraft -Agricultural workers -Cavers -Civil engineers -Coppersmiths -Dying people -Erysipelas -Europe -Farmers -Fever -Gall stones -Heerdt (Germany) -Inflammatory diseases -Italian architects -Kidney disease -Monks -Nettle rash -Norcia (Italy) -People in religious orders -Schoolchildren -Servants who have broken their master's belongings -Speliologists -Spelunkers -Temptations |

Benedict of Nursia (in Italian, Benedetto da Norcia) (c. 480 - c. 547) was a saint from Italy, the founder of Western Christian monastic communities, and a rule-giver for cenobitic monks. His purpose may be gleaned from his Rule, namely that "Christ ... may bring us all together to life eternal."[1] He was canonized by the Roman Catholic Church in 1220.

Benedict founded twelve communities for monks, the best known of which is his first monastery, at Monte Cassino in the mountains of southern Italy. There is no evidence that he intended to found a religious order. The Order of St Benedict is of modern origin and, moreover, not an "order" as commonly understood but merely a confederation of autonomous congregations.[2]

Benedict's main achievement is his "Rule", containing precepts for his monks. It is heavily influenced by the writings of John Cassian, and shows strong affinity with the Rule of the Master. But it also has a unique spirit of balance, moderation and reasonableness (επιεικεια, epieikeia), and this persuaded most religious communities founded throughout the Middle Ages to adopt it. As a result, the Rule of St Benedict became one of the most influential religious rules in Western Christendom. For this reason Benedict is often called the founder of western Christian monasticism.

Contents |

Biography

The only ancient account of Benedict is found in the second volume of Pope Gregory I's four-book Dialogues, written in 593. Book Two consists of a prologue and thirty-eight succinct chapters. 19th-century Roman historian Thomas Hodgkin praised Gregory’s life of St. Benedict as “the biography of the greatest monk, written by the greatest Pope, himself also a monk.”[3]

Gregory’s account of this saint’s life is not, however, a biography in the modern sense of the word. It provides instead a spiritual portrait of the gentle, disciplined abbot. In a letter to Bishop Maximilian of Syracuse, Gregory states his intention for his Dialogues, saying they are a kind of floretum (an anthology, literally, ‘flowers’) of the most striking miracles of Italian holy men.[4]

Gregory did not set out to write a chronological, historically-anchored story of St. Benedict, but he did base his anecdotes on direct testimony. To establish his authority, Gregory explains that his information came from what he considered the best sources: a handful of Benedict’s disciples who lived with the saint and witnessed his various miracles. These followers, he says, are Constantinus, who succeeded Benedict as Abbot of Monte Cassino; Valentinianus; Simplicius; and Honoratus, who was abbot of Subiaco when St. Gregory wrote his Dialogues.

In Gregory’s day, history was not recognized as an independent field of study; it was a branch of grammar or rhetoric, and historia (defined as ‘story’) summed up the approach of the learned when they wrote what was, at that time, considered ‘history.’[5] Gregory’s Dialogues Book Two, then, an authentic medieval hagiography cast as a conversation between the Pope and his deacon Peter, is designed to teach spiritual lessons.

Early life

Benedict was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia, the modern Norcia, in Umbria. A tradition which Bede accepts makes him a twin with his sister Scholastica. St Gregory's narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than 19 or 20. He was old enough to be in the midst of his literary studies, to understand the real meaning and worth of the dissolute and licentious lives of his companions, and to have been deeply affected himself by the love of a woman (Ibid. II, 2). He was capable of weighing all these things in comparison with the life taught in the Gospels, and chose the latter. He was at the beginning of life, and he had at his disposal the means to a career as a Roman noble; clearly he was not a child. If we accept the date 480 for his birth, we may fix the date of his abandonment of his studies and leaving home at about 500 AD.

Benedict does not seem to have left Rome for the purpose of becoming a hermit, but only to find some place away from the life of the great city. He took his old nurse with him as a servant and they settled down to live in Enfide, near a church to St Peter, in some kind of association with "a company of virtuous men" who were in sympathy with his feelings and his views of life. Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbruini mountains, about forty miles from Rome and two from Subiaco.

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. Crossing the Aniene and turning to the right, the path rises along the left face off the ravine and soon reaches the site of Nero's villa and of the huge mole which formed the lower end of the middle lake; across the valley were ruins of the Roman baths, of which a few great arches and detached masses of wall still stand. Rising from the mole upon 25 low arches, the foundations of which can even yet be traced, was the bridge from the villa to the baths, under which the waters of the middle lake poured in a wide fall into the lake below. The ruins of these vast buildings and the wide sheet of falling water closed up the entrance of the valley to St Benedict as he came from Enfide; to-day the narrow valley lies open before us, closed only by the far-off mountains. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine, on which it runs, becomes steeper, until we reach a cave above which the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right, it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in St Benedict's day, 500 feet below, lay the blue waters of the lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep.

On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus of Subiaco, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus had discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and had given him the monk's habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years, unknown to men, lived in this cave above the lake.

Later life

St. Gregory tells us little of these years. He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (puer), but as a man (vir) of God. Romanus, he twice tells us, served the saint in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, Benedict matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with Vicovaro), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that "their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent" (ibid., 3). The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him, and he returned to his cave. The legend goes that they first tried to poison his drink. He prayed a blessing over the cup and the cup shattered. Then they tried to poison him with poisoned bread. When he prayed a blessing over the bread, a raven swept in and took the loaf away. From this time his miracles seem to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. For them he built in the valley twelve monasteries, in each of which he placed a superior with twelve monks. In a thirteenth he lived with a few, such as he thought would more profit and be better instructed by his own presence (ibid., 3). He remained, however, the father, or abbot, of all. With the establishment of these monasteries began the schools for children; and among the first to be brought were Maurus and Placid.

St Benedict spent the rest of his life realizing the ideal of monasticism which he had drawn out in his rule. He died at Monte Cassino, Italy, according to tradition, on 21 March 547 and was named patron protector of Europe by Pope Paul VI in 1964. [6] His feast day, previously 21 March, was moved in 1969 to 11 July, a date on which, in many areas, he was traditionally celebrated since the eighth century, because otherwise it would every year be impeded by the observance of Lent, during which there are no obligatory Memorials.[7]

Rule of St. Benedict

“A lamb can bathe in it without drowning, while an elephant can swim in it”; this ancient saying refers to a work of only 73 short chapters. Its wisdom is of two kinds: spiritual (how to live a Christocentric life on earth) and administrative (how to run a monastery efficiently). More than half the chapters describe how to be obedient and humble, and what to do when a member of the community is not. About one-fourth regulate the worship of God (the Opus Dei). One-tenth outline how, and by whom, the monastery should be managed. And another tenth specifically describe the abbot’s pastoral duties.

The Saint Benedict Medal

This medal originally came from a cross in honor of St Benedict. On one side, the St Benedict medal has an image of Benedict, holding the Holy Rule in his left hand and a cross in his right. There is a raven on one side of him, with a cup on the other side of him. Around the medal's outer margin is "Eius in obitu nostro praesentia muniamur" ("May we, at our death, be fortified by His presence"). The other side of the medal has a cross with the initials for the words "Crux Sacra Sit Mihi Lux" ("May the Holy Cross be my light") on the vertical beam and the initials for "Non Draco Sit Mihi Dux" ("Let not the dragon be my guide") on the horizontal beam. The initial letters for "Crux Sancti Patris Benedicti" ("The Cross of Our Holy Father Benedict") are on the interior angles of the cross. Around the medal's margin on this side are the initials for "Vade Retro Satana, Nunquam Suade Mihi Vana—Sunt Mala Quae Libas, Ipse Venena Bibas" ("Begone, Satan, do not suggest to me thy vanities—evil are the things thou profferest, drink thou thy own poison"). Either the inscription "Pax" (Peace) or the Christogram "IHS" is located at the top of the cross in most cases.

This medal was first struck in 1880 to commemorate the fourteenth centenary of St Benedict's birth and is also called the Jubilee Medal; its exact origin, however, is unknown. In 1647, during a witchcraft trial at Natternberg near Metten Abbey in Bavaria, the accused women testified they had no power over Metten, which was under the protection of the cross. An investigation found a number of painted crosses on the walls of the abbey with the letters now found on St Benedict medals, but their meaning had been forgotten. A manuscript written in 1415 was eventually found that had a picture of Saint Benedict holding a scroll in one hand and a staff which ended in a cross in the other. On the scroll and staff were written the full words of the initials contained on the crosses. Medals then began to be struck in Germany, which then spread throughout Europe. This medal was first approved by Pope Benedict XIV in his briefs of December 23, 1741, and March 12, 1742.

Saint Benedict has been also the motive of many collector's coins around the world. One of the most prestigious and recent ones is the Austria 50 euro 'The Christian Religious Orders', issued in March 13, 2002.

The influence of St. Benedict

The early middle ages have been called "the Benedictine centuries."[8] In April 2008, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the influence St. Benedict had on Western Europe. The pope said that “with his life and work St. Benedict exercised a fundamental influence on the development of European civilization and culture” and helped Europe to emerge from the "dark night of history" that followed the fall of the Roman empire.[9]

The influence of St. Benedict produced "a true spiritual ferment" in Europe, and over the coming decades his followers spread across the continent to establish a new cultural unity based on Christian faith.

In 1964, Pope Paul VI named St. Benedict as patron saint of Europe.[10]

See also

- Anthony the Great

- Benedictine Order

- Camaldolese

- Hermit

- Poustinia

References

- ↑ RB 72.12

- ↑ Called into existence by Pope Leo XIII's Apostolic Brief "Summum semper", 12 July 1893, see OSB-International website

- ↑ See Life and Miracles of St. Benedict (Book II, Dialogues), translated by Odo John Zimmerman, O.S.B. and Benedict R. Avery, O.S.B. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980), p. iv.

- ↑ See Ildephonso Schuster, Saint Benedict and His Times, Gregory J. Roettger, trans. (London: B. Herder, 1951), p. 2.

- ↑ See Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, editor, Historiography in the Middle Ages (Boston: Brill, 2003), pp. 1-2.

- ↑ "St. Bendict of Nursia". Catholic Online. Retrieved on 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana), pp. 97 and 119

- ↑ "Western Europe in the Middle Ages". Retrieved on 2008-11-17.

- ↑ Benedict XVI, "Saint Benedict of Norcia" Homily given to a general audience at St Peter's Square on Wednesday, 9 April 2008 http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080409_en.html

- ↑ Catholic World News: St. Benedict and the key to European unity

This article incorporates text from the public-domain Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913.

External links

- A Benedictine Oblate Priest - The Rule in Parish Life

- Guide to Saint Benedict

- Sacro speco, Grotta della Preghiera – general view " – enlarged view

- The Holy Rule of St. Benedict - Online translation by Rev. Boniface Verheyen, OSB, of St. Benedict's Abbey

- The Order of Saint Benedict

- The Medal Or Cross of St. Benedict: Its Origin, Meaning, and Privileges

- Life and Miracles of St Benedict

- Works by or about Benedict of Nursia in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- "The Life of St. Benedict: Introduction". Retrieved on 2008-11-17.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||