Beluga (whale)

| Beluga[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

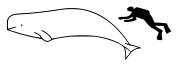

Size comparison against an average human

|

||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||

| Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas, 1776) |

||||||||||||||

Beluga range

|

The Beluga or White Whale (Delphinapterus leucas) is an Arctic and sub-Arctic species of cetacean. It is one of two members of the family Monodontidae, along with the Narwhal. This marine mammal is commonly referred to simply as the Beluga or Sea Canary due to its high-pitched twitter.[3] It is up to 5 m (15 ft) in length and an unmistakable all white in color with a distinctive protuberance on the head. Belugas from the Cook Inlet in Alaska have been placed under the protection of the Endangered Species Act by the U.S. federal government.[4]

Contents |

Taxonomy and evolution

The Beluga was first described by Peter Simon Pallas in 1776. It is a member of the Monodontidae family, which is in turn part of the toothed whale suborder.[1] The Irrawaddy Dolphin was also once considered to be in the same family; however, recent genetic evidence suggests otherwise.[5] The only other species within the Monodontidae family besides the Beluga is the Narwhal.[6]

The earliest known ancestor of the Beluga is the prehistoric Denebola brachycephala from the late Miocene period. One single fossil has been found on the Baja California peninsula, indicating that the family once existed in warmer waters. The fossil record also indicates that in comparatively recent times the Beluga's range has varied with that of the ice pack–expanding during ice ages and contracting when the ice retreats.

The Red List of Threatened Species gives both Beluga and White Whale as common names, though the former is now more popular. The English name comes from the Russian белуга (beluga) or белуха (belukha) which derives from the word белый (belyy), meaning "white". It is sometimes referred to by scientists as the Belukha Whale in order to avoid confusion with the beluga sturgeon. The whale is also colloquially known as the Sea Canary on account of the high-pitched squeaks, squeals, clucks and whistles.

A Japanese researcher says he has taught a Beluga to "talk" by using these sounds to identify three different objects, offering hope that humans may one day be able to hold conversations with sea mammals.[7]

Description

Male Belugas are larger than females. Males can reach 5.5 metres (18 ft) long, while females grow to as much as 4.1 metres (13 ft).[8] Males weigh between 1,100 and 1,600 kilograms (2,400 and 3,500 lb) while females weigh between 700 and 1,200 kilograms (1,500 and 2,600 lb).[9] This is larger than all but the largest dolphins but smaller than most other toothed whales.

This whale is unmistakable when adult: it is all white or whitish grey. Calves, however, are usually gray.[8] The head is unlike that of any other cetacean. Like most toothed whales it has a melon, an oily, fatty lump of tissue found at the center of the forehead. But the Beluga's melon is extremely bulbous and even malleable.[6] The Beluga is able to change the shape of its head by blowing air around its sinuses. Again unlike many dolphins and whales, the vertebrae in the neck are not fused together, allowing the animal flexibility to turn its head laterally. The rostrum has about 8 to 10 teeth on each side of the jaw.

It has a dorsal ridge rather than a dorsal fin.[8] The absence of the dorsal fin is reflected in the genus name of the species - apterus is the Greek word for "wingless". The evolutionary preference for a dorsal ridge rather than a fin is believed by scientists to be adaptation to under-ice conditions, or possibly as a way of preserving heat.[6] Like in other cetaceans the thyroid gland is relatively large compared to terrestrial mammals (three times per weight as a horse) and may help to sustain higher metabolism during the summer estuarine occupations.

The body of the Beluga is round, particularly when well-fed, and tapers smoothly to both the head and tail. The tail fin grows and becomes increasingly ornately curved as the animal ages. The flippers are broad and short - making them almost square-shaped.

Distribution

The Beluga inhabits a discontinuous circumpolar distribution in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters ranging from 50° N to 80° N, particularly along the coasts of Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia. The southernmost extent of the range includes isolated populations in the St. Lawrence River estuary and the Saguenay fjord, around the village of Tadoussac, Quebec, in the Atlantic and the Amur River delta, the Shantar Islands and the waters surrounding Sakhalin Island in the Sea of Okhotsk.[10]

In the spring the Beluga moves to its summer grounds, bays, estuaries and other shallow inlets. These summer sites are detached from one another and a mother will usually return to the same site year after year. As its summer homes become clogged with ice during autumn, the Beluga moves away for winter. Most travel in the direction of the advancing ice-pack and stay close to the edge of it for the winter months. Others stay under the iced area–surviving by finding ice leads and polynyas (patches of open water in the ice) in which they can surface to breathe. Beluga may also find pockets of air trapped under the ice. The remarkable ability of the Beluga to find the thin slivers of open water where the dense ice pack may cover more than 96% of the sea surface is still a source of mystery and great interest to scientists. It is clear that the echo-location capabilities of the Beluga are highly adapted to the peculiar acoustics of the sub-ice sea and it has been suggested that Beluga can sense open water through echolocation.

On June 9 2006, the carcass of a young Beluga was found in the Tanana River near Fairbanks in central Alaska, nearly 1,700 kilometres (1,100 miles) from its nearest natural ocean habitat. As Beluga sometimes follow migrating fish, Alaska state biologist Tom Seaton speculated that it had followed migrating salmon up the river at some point in the prior fall.

Behavior

The Beluga is a highly sociable creature. Groups of males may number in the hundreds, but mothers with calves generally mix in slightly smaller groups. When pods do aggregate in estuaries, they may number in the thousands. This can represent a significant proportion of the entire Beluga population and is the time when they are most vulnerable to hunting.

Beluga pods tend to be unstable, meaning that Belugas tend to move from pod to pod. Pod membership is rarely permanent. Radio-tracking has shown Belugas can start out in a pod and within a few days be hundreds of miles away from that pod. The closest social relationship between Belugas is the mother-calf relationship. Nursing times of two years have been observed and lactational anestrus may not occur. Calves often return to the same estuary as their mother in the summer, meeting with their mother sometimes even after becoming fully mature.

Beluga are also known for being rather playful, as well as spitting at humans or other whales. It is not unusual for an aquarium handler to be sprayed down by one of his charges whilst tending a Beluga tank. Some researchers believe that this skill may be utilized to blow away sand from crustaceans at the sea bottom. Unlike most whales, it is capable of swimming backwards.[11]

Diet

The Beluga is a slow-swimming mammal which feeds mainly on fish. It also eats cephalopods (squid and octopus) and crustaceans (crab and shrimp). Foraging on the seabed typically takes place at depths of up to 1,000 feet, but they can dive at least twice this depth. Generally a feeding dive will last 3–5 minutes, but Belugas have been observed submerged for up to 20 minutes at a time.[12]

Reproduction

Female Belugas generally give birth every three years.[8] Most mating occurs between February and May, but some mating does occur at other times of year.[8][6] It is questionable whether the Beluga can have delayed implantation.[6] The gestation period is 12 to 14 1/2 months.[8]

Calves are born over a protracted period that varies by location. In the Canadian Arctic, calves are born between March and September, while in Hudson Bay the peak calving period is in late June and in Cumberland Sound most calves are born from late July to early August.[13]

Newly-born calves are about 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) long and weigh about 80 kilograms (180 lb) and are grey in color. The calves remain dependent on their mothers for at least two years. Male Belugas reach sexual maturity between four and seven years, while females reach sexual maturity between six and nine years. The Beluga can live for more than 50 years.[8]

Population, threats, and human interactions

The global population of Beluga today stands at about 100,000. Although this number is much greater than that of other cetaceans, it is much smaller than historical populations before decades of over-hunting. There are estimated to be 40,000 individuals in the Beaufort Sea, 25,045 in Hudson Bay, 18,500 in the Bering Sea and 28,008 in the Canadian Low Arctic. The population in the St. Lawrence estuary is estimated to be around 1000.[14] It is considered an excellent sentinel species and indicator of the health of, and changes in, the environment. This is because it is long lived, on top of the food web, with large amounts of fat and blubber, relatively well studied for a cetacean, and still somewhat common.

The Beluga's natural predators are the Polar Bear, who hunt when the whales become encircled by ice during winter. The bears take particular advantage of situations when Belugas become trapped by ice and are thus unable to reach the ocean. The bears swipe at the Belugas and drag them onto the ice. The Orca is the other significant natural predator of the Beluga.[9]

Because the Beluga congregates in river estuaries, human-caused pollution is proving to be a significant danger to its health. Incidents of cancer have been reported to be rising as a result of the St. Lawrence River pollution. The bodies of the Beluga inhabiting this area contain so many contaminants that their carcasses are treated as toxic waste. Reproductive pathology has been discovered in the population here and many suspect organochlorines to be responsible. Levels between 240 ppm and 800 ppm of PCBs have been found, with males typically having higher levels.[15] It is not known what the long-term effects of this pollution will be on the affected populations.

Belugas were amongst the first whale species to be brought into captivity. The first Beluga was shown at Barnum's Museum in New York in 1861. Today it remains one of the few whale species kept at aquaria and sea life parks across North America, Europe and Asia. Its popularity there with visitors reflects its attractive color, and its range of facial expressions. While most cetacean "smiles" are fixed, the extra movement afforded by the Beluga's unfused cervical vertebrae allows a greater range of expression. Most Beluga found in aquariums are caught in the wild, though captive breeding programs have enjoyed some success.

Indirect human disturbance may also be a threat to the species. While some populations have come to tolerate small boats, others have been known to actively try to avoid ships. Whale-watching Beluga has become a huge and booming activity in the St. Lawrence and Churchill River areas.

Because of its predictable migration pattern and high concentrations, the Beluga has been hunted by indigenous Arctic peoples for centuries. In many areas a pattern of hunting, believed to be sustainable, continues to this day. However, in other areas, such as the Cook Inlet, Ungava Bay, and off west Greenland, previous commercial catches left the populations in great peril. Indigenous whaling continues in these areas, and some populations continue to decline. These areas are the subject of intensive dialogue between Inuit communities and national governments aiming to create a sustainable hunt.

The Beluga population from Cook Inlet Alaska is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, Species of Concern.[16] In addition, the Cook Inlet Beluga population was proposed to be listed as Endangered under the ESA in April 2007.[17] A final decision was expected in April 2008, but the NMFS used a one-time six-month extension request in order to perform the 2008 survey and digest the data. In October 2008, the federal government placed the whales under the protection of the Endangered Species Act.[18][4]

Both the United States Navy and the Russian Navy have used Belugas in anti-mining operations in Arctic waters.[19]

Pathogens

Papillomaviruses have been found in the gastric compartments of Belugas in the St. Lawerence River. Herpesvirus as well has been detected on occasion in Belugas. Encephalitis has sometimes been observed and the protozoa Sarcocystis can infect the animals. Ciliates have been observed to colonize the blowhole yet may not be pathogenic or especially harmful.[20]

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae gram positive/variable bacilli, likely from contaminated fish in the diet, can endanger captive Belugas causing anorexia, dermal plaques, and lesions. This may lead to death if not diagnosed early and treated with antibiotics..[21]

Conservation status

As of 2008, the Beluga is listed as "near threatened" by the IUCN. This is due to uncertainty about the global number of Belugas over parts of its range (especially the Russian Arctic) and the expectation that if current conservation efforts cease, especially management of hunting, the Beluga population is likely to qualify for "threatened" status within five years. Prior to 2008, the Beluga was listed as "vulnerable", which represented a higher level of concern. The reason given by IUCN for the change in status is that some of the largest subpopulations are not declining and because improved census methods have indicated that the population size is larger than previously estimated.[2]

Subpopulations are subject to differing levels of threat and warrant individual assessment. The Cook Inlet subpopulation of the Beluga is listed as "Critically Endangered" by the IUCN as of 2006".[22] This was due to overharvesting of Beluga's prior to 1998, and the population has failed to show expected signs of recovery even though the reported harvest has been small. The most recent published estimate at the time of the present assessment (May 2008) was 302 (CV=0.16) in 2006 (Angliss and Outlaw 2007). In addition, the National Marine Fisheries Service had indicated via a web posting that the point estimate from the 2007 aerial survey was 375.

Gallery

See also

- Baby Beluga, a song and album by children's singer Raffi

- Airbus Beluga, a cargo aircraft.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mead, James G. and Robert L. Brownell, Jr (November 16 2005). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14300105.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Jefferson, T.A., Karczmarski, L., Laidre, K., O’Corry-Crowe, G., Reeves, R.R., Rojas-Bracho, L., Secchi, E.R., Slooten, E., Smith, B.D., Wang, J.Y. & Zhou, K. (2008). Delphinapterus leucas. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2008. Retrieved on 2008-10-07.

- ↑ Harris, Patricia; Lyon, David; (April 8, 2007) Boston Globe Enter close quarters: colonial to nuclear subs. Section: Travel; Page 8M.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Rosen, Yereth (October 17, 2008). "Beluga whales in Alaska listed as endangered", Reuters. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

- ↑ Arnold, P. (2002). "Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris". in Perrin, W., Würsig B. and Thewissen, J.. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 652. ISBN 0-12-551340-2.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 O'Corry-Crowe, G. (2002). "Beluga Whale Delphinapterus leucas". in Perrin, W., Würsig B. and Thewissen, J.. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. p. 94-99. ISBN 0-12-551340-2.

- ↑ "Japanese whale whisperer teaches beluga to talk". www.meeja.com.au (2008-09-16). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Shirihai, H. & Jarrett, B. (2006). Whales, Dolphins and Other Marine Mammals of the World. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press. p. 97–100. ISBN 0-69112757-3.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Reeves, R., Stewart, B., Clapham, P. & Powell, J. (2003). Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. New York: A.A. Knopf. p. 318–321. ISBN 0-375-41141-0.

- ↑ Artyukhin Yu.B. and V.N. Burkanov (1999). Sea birds and mammals of the Russian Far East: a Field Guide, Мoscow: АSТ Publishing – 215 p. (Russian)

- ↑ "Georgia Aquarium - Beluga Whale". Retrieved on 2008-10-12.

- ↑ "Delphinapterus leucas: Beluga Whale", Marine Bio. Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Cosens, S. & Dueck, L. (June 1990). "Spring Sightings of Narwhal and Beluga Calves in Lancaster Sound, N.W.T". Arctic 31 (2): 1–2. http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic43-2-127.pdf.

- ↑ Portrait of endangered beluga whales in Quebec

- ↑ J Great Lakes Res.,19 & Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.,16 & Sci. Total Environ.,154

- ↑ "Proactive Conservation Program: Species of Concern". National Marine Fisheries Service. Retrieved on 2008-09-17.

- ↑ "Endangered and Threatened Species; Proposed Endangered Status for the Cook Inlet Beluga Whale". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2007-04-20). Retrieved on 2008-09-17.

- ↑ Herbert, H. Josef (October 17, 2008). "Government declares beluga whale endangered", Associated Press. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

- ↑ "The Story of Navy Dolphins". PBS. Retrieved on 2008-10-12.

- ↑ Dierauf, L. & Gulland, F. (2001). CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine. CRC Press. p. 26, 303, 359. ISBN 0849308399.

- ↑ Dierauf, L. & Gulland, F. (2001). CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine. CRC Press. p. 316–317. ISBN 0849308399.

- ↑ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved on 2008-10-17.

Further reading

- Outridge, P. M., K. A. Hobson, R. McNeely, and A. Dyke. 2002. "A Comparison of Modern and Preindustrial Levels of Mercury in the Teeth of Beluga in the Mackenzie Delta, Northwest Territories, and Walrus at Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada". Arctic. 55: 123-132.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||