Belarusian language

| Belarusian/Belorussian беларуская мова BGN/PCGN: byelaruskaya mova

|

||

|---|---|---|

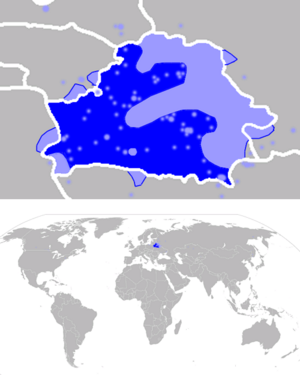

| Spoken in: | Belarus, Poland, in 14 other countries | |

| Total speakers: | 4 to 7 million | |

| Ranking: | 74 | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic East Slavic Belarusian/Belorussian |

|

| Writing system: | Cyrillic | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | ||

| Regulated by: | National Academy of Sciences of Belarus | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | be | |

| ISO 639-2: | bel | |

| ISO 639-3: | bel | |

|

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

The Belarusian language, or Belorussian (беларуская мова, BGN/PCGN: byelaruskaya mova, Scientific: belaruskaja mova, Łacinka: biełaruskaja mova) is the language of the Belarusian people and is spoken in Belarus and abroad, chiefly in Russia, Ukraine, and Poland.[1] Prior to Belarus gaining its independence from the Soviet Union in 1992, the language was called "Byelorussian" or "Belorussian" (in accordance with the ethnicity and country names: Byelorussians, Byelorussia, the latter being a transliteration from the Russian language.). It belongs to the group of the East Slavonic languages, and shares many grammatical and lexical features with other members of the group. Its predecessor was the Old Belarusian language (up to the 19th cent., conventionally).

In Belarus, the Belarusian language is declared as a "language spoken at home" by about 3,686,000 people (36.7% of the population)[2] as of 1999.[3] By less strict criteria, about 6,984,000 (85.6%) of Belarusians declare it their "mother tongue". Other sources put down the "population of the language" as 6,715,000 in Belarus and 9,081,102 in all countries.[4][5]

The Belarusian language is the official language of Belarus, along with Russian.[6]

Contents |

Phonology

The phoneme inventory of the modern Belarusian language consists of 45 to 54 phonemes: 6 vowels and 39 to 48 consonants, depending on how they are counted. Usually, the number is given as 39, which excludes the nine geminate consonants as "mere variations". Sometimes, rare consonants are also excluded, thus bringing the quoted number of consonants further down. The number 48 includes all consonant sounds, including variations and rare sounds, which may have a "phonetic" meaning in the modern Belarusian language.

Alphabet

The Belarusian alphabet is a form of the Cyrillic alphabet, which was first used for the Old Church Slavonic language. The modern Belarusian form was determined in 1918, and consists of thirty-two letters. The Glagolitic script had been used, sporadically, until 11th or 12th century. In the past Belarusian has also been written in the Belarusian Latin alphabet (Łacinka / Лацінка) and the Belarusian Arabic alphabet.

There exist several notable systems of romanizing (transliterating) written Belarusian text; see Romanization of Belarusian.

Grammar

Standardized Belarusian grammar in its modern form was adopted in 1959, with minor amendments in 1985. It was developed from the initial form set down by Branislaw Tarashkyevich (first printed in Vilnius, 1918). Historically, there had existed several other alternative standardized forms of Belarusian grammar.

Dialects

Besides the literary norm, there exist two main dialects of the Belarusian language, the North-Eastern and the South-Western. In addition, there exist the transitional Middle Belarusian dialect group and the separate West Palyesian dialect group.

The North-Eastern and the South-Western dialects are separated by the highly conventional imaginary line Ashmyany–Minsk–Babruysk–Homyel, with the area of the Middle Belarusian dialect group placed on and along this line.

The North-Eastern dialect is chiefly characterised by the "soft sounding R" (мягка-эравы) and "strong akanye" (моцнае аканне), and the South-Western dialect is chiefly characterised by the "hard sounding R" (цвёрда-эравы) and "moderate akanye" (умеранае аканне).

The West Palyesian dialect group is more distinct linguistically, close to Ukrainian language in many aspects, and is separated by the conventional line Pruzhany–Ivatsevichy–Tsyelyakhany–Luninyets–Stolin.

Names

There are quite a number of various names under which the Belarusian language has been known, both contemporary and historical, some of them quite dissimilar, especially when referring to the Old Belarusian period.

Official, romanised

- Belarusian (also spelled Belarusan, Belarussian, Byelarussian) – derived from the Belarusian name of the country "Belarus", officially approved for the use abroad by the Belarusian authorities (ca. 1992) and promoted since then.

- Byelorussian (also spelled Belorussian, Bielorussian ) – derived from the Russian name of the country "Byelorussia" (Russian: Белоруссия), used officially (in the Russian language) in the times of the USSR, and, later, in Russia.

- White Russian, White Ruthenian (and its equivalents in other languages) – literal, word-by-word translation of the parts of the composite word Belarusian.

Alternative

- Great Lithuanian (вялікалітоўская (мова)) – proposed and used by Yan Stankyevich since the 1960s, intended to part with the "diminishing tradition of having the name related to the Muscovite tradition of calling the Belarusian lands" and to pertain to the "great tradition of Belarusian statehood".

- Kryvian or Krivian (крывіцкая/крывічанская/крыўская (мова), Polish: język krewicki) – derived from the name of the Slavonic tribe Krivichi, one of the main tribes in the foundations of the forming of the Belarusian nation. Created and used in the 19th century by Belarusian Polish-speaking writers Jaroszewicz, Narbut, Rogalski, Jan Czeczot. Strongly promoted by Vaclau Lastouski.

Vernacular

- Simple (простая (мова)) or local (тутэйшая (мова)) – used mainly in times preceding the common recognition of the existence of the Belarusian language, and nation in general. Supposedly, the term can still be encountered up to the end of the 1930s, e.g., in Western Belarus.

- Simple Black Ruthenian (Russian: простой чернорусский) – used in the beginning of the 19th century by the Russian researcher Baranovski and attributed to contemporary vernacular Belarusian.[7]

|

History

The modern Belarusian language was redeveloped on the base of the vernacular spoken remnants of the Old Belarusian language, surviving on the ethnic Belarusian lands in the 19th century. The end 18th century (the times of the Divisions of Commonwealth) is the usual conventional borderline between the Old Belarusian language and Modern Belarusian language stages of development.

By the end 18th century, the (Old) Belarusian language still enjoyed some popularity among the smaller nobility in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL). Jan Czeczot in 1840s had mentioned that even his generation’s grandfathers preferred speaking (Old) Belarusian.[8] (According to A. N. Pypin, the Belarusian language was still being spoken here and there among the smaller nobility during the 19th century.[9]) The Belarusian, in its vernacular form, was the language of the smaller town dwellers and of the peasantry. It had been the language of the oral forms of the folk lore. The teaching in Belarusian was conducted mainly in the schools run by the Basilian order.

The development of the Belarusian language in the 19th century was strongly influenced by the political conflict in the territories of the former GDL, between the Russian Imperial authorities, trying to consolidate their rule over the "joined provinces" and the Polish and Polonised nobility, trying to bring back its pre-Partitions rule[10] (see also: Polonization in times of Partitions).

One of the important manifestations of this conflict was the struggle for the ideological control over the educational system. The Polish and Russian language were being introduced and re-introduced in it, while the general state of the people's education remained appalling until the very end of the Russian Empire.[11]

Summarily, the 1800s–1820s had seen the unprecedented prosperity of the Polish culture and language in the former GDL lands, had prepared the era of such famous «Belarusians by birth – Poles by choice», as Mickiewicz and Syrokomla. The era had seen the effective completion of the Polonization of the smallest nobility, the further reduction of the areal of use of the contemporary Belarusian language, and the effective folklorization of the Belarusian culture.[12]

Due both to the state of the people's education and to the strong positions of Polish and Polonised nobility, it was only since the 1880s–1890s, that the educated Belarusian element, still shunned because of "peasant origin", began to appear in the state offices.[13]

In 1846, ethnographer Shpilevskiy prepared the Belarusian grammar (using Cyrillic alphabet) on the basis of the folk dialects of the Minsk region. However, the Russian Academy of Sciences refused to print his submission, on the basis that it had not been prepared in a sufficiently scientific manner.

Since mid-1830s, the ethnographical works began to appear, the tentative attempts of study of language were uptaken (e.g., Belarusian grammar by Shpilevskiy). The Belarusian literature tradition began to re-form, basing on the folk language, initiated by the works of Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich. See also: Jan Czeczot, Jan Borszczewski.[14]

In beg. 1860s, both Russian and Polish parties in Belarusian lands had begun to realise the that the decisive role in the upcoming conflicts was shifting to the peasantry, overwhelmingly Belarusian. So, quite an amount of propaganda appeared, targeted at peasantry and prepared in Belarusian language.[15] Notably, the anti-Russian, anti-Tsarist, anti-Orthodox "Manifest" and newspaper "Peasants' Truth" (1862–1863) by Kalinowski, the anti-Polish, anti-Revolutionary, pro-Orthodox booklets and poems (1862).[16]

The advent of the all-Russian "narodniki" and Belarusian national movements (end 1870s – beg. 1880s) renewed the interest in Belarusian language (see also: Homan (1884), Bahushevich, Yefim Karskiy, Dovnar-Zapol'skiy, Bessonov, Pypin, Sheyn, Nosovich). The Belarusian literary tradition was renewed, too ((see also: F. Bahushevich). It was in these times that F. Bahushevich made his famous appeal to Belarusians: "Do not forsake our language, lest you pass away" (Belarusian: Не пакідайце ж мовы нашай, каб не ўмёрлі).

In course of the 1897 Russian Empire Census, about 5.89 million people declared themselves speakers of Belarusian language.

| Guberniya* | Total Population | Belarusian (Beloruskij) | Russian (Velikoruskij) | Polish (Polskij) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vilna | 1,591,207 | 891,903 | 78,623 | 130,054 |

| Vitebsk | 1,489,246 | 987,020 | 198,001 | 50,377 |

| Grodno | 1,603,409 | 1,141,714 | 74,143 | 161,662 |

| Minsk | 2,147,621 | 1,633,091 | 83,999 | 64,617 |

| Mogilev | 1,686,764 | 1,389,782 | 58,155 | 17,526 |

| Smolensk | 1,525,279 | 100,757 | 1,397,875 | 7,314 |

| Chernigov | 2,297,854 | 151,465 | 495,963 | 3,302 |

| Vistula guberniyas | 9,402,253 | 29,347 | 335,337 | 6,755,503 |

| All Empire | 125,640,021 | 5,885,547 | 55,667,469 | 7,931,307 |

| * See also: Administrative-territorial division of Belarus and bordering lands in 2nd half 19 cent. (right half-page) and Ethnical composition of Belarus and bordering lands (prep. by Mikola Bich on the basis of 1897 data) | ||||

The end of the 19th century however still showed that the urban language of Belarusian towns remained either Polish or Russian and in the same census towns exceeding 50000 had Belarusian speakers of less than a tenth. This state of affairs greatly contributed to a perception that Belarusian is a "rural" and "uneducated" language.

However the census was a major breakthrough for the first steps of the Belarusian national self-conscience and identity, as it clearly showed to the Imperial authorities, and the still strong Polish minority that the population and the language was neither Polish nor Russian.

1900s-1910s

The rising influence of the Socialist ideas advanced the process of emancipating of the Belarusian language still further (see also: Belarusian Socialist Assembly, Circle of Belarusian People's Education and Belarusian Culture, Belarusian Socialist Lot, Socialist Party "White Russia", Tsyotka, Nasha Dolya). The fundamental works of Yefim Karskiy marked a turning point in the scientific perception of Belarusian language. The ban on the publishing in Belarusian was officially raised (1904-12-25). The unprecedented surge of the national feeling, especially among the workers and peasants, coming in the 1900s, esp. after the events of 1905,[17] gave momentum to the intensive development of the Belarusian literature and press (see also: Naša niva, Yanka Kupala, Yakub Kolas).

Grammar

During the 19th - beg. 20th cent., there was no normative Belarusian grammar. Authors wrote as they saw fit, usually representing the particularities of different Belarusian dialects. The scientific groundwork for the introduction of a truly scientific and modern grammar of the Belarusian language was laid down by linguist Yefim Karskiy.

By the beg. 1910s, the continuing lack of a codified Belarusian grammar was becoming intolerably obstructive. Then Russian academician Shakhmatov, chair of the Russian language and literature department of St. Petersburg University, approached the board of the Belarusian newspaper Naša niva with such a proposal, that the Belarusian linguist would be trained under his supervision in order to be able to prepare the grammar. Initially, famous Belarusian poet Maksim Bahdanovich was to be entrusted with this work. However, Bahdanovich's poor health (tuberculosis) precluded his living in the climate of St. Petersburg. So, Branislaw Tarashkyevich, a fresh graduate of the Vilnya Liceum No.2, was selected for the task.

In the Belarusian community, great interest was vested in this enterprise. The already famous then Belarusian poet Yanka Kupala, in his letter to Tarashkyevich, urged him to "hurry with his much-needed work". Tarashkyevich had been working on the preparation of the grammar during 1912–1917, with help and supervision of academicians Shakhmatov and Karskiy. Tarashkyevich had completed the work by the Fall 1917, even having to go from the tumultuous Petrograd of 1917 to relatively calm Finland in order to be able to complete it uninterrupted.

By Summer 1918, it became obvious, that there were insurmountable problems with the printing of Tarashkyevich's grammar in Petrograd – a lack of paper, type and qualified personnel. Meanwhile, Tarashkyevich's grammar had apparently been slated for adoption in the workers' and peasants' schools of Belarus that were to be set up. So, Tarashkyevich was permitted to print his book abroad. In June 1918, Tarashkyevich arrived in Vil'nya, via Finland. The Belarusian Committee petitioned for the administration to allow the book to be printed. Finally, the 1st edition of the «Belarusian grammar for schools» was printed (Vil'nya, 1918).

There existed at least two other contemporary attempts at codification of the Belarusian grammar. In 1915, rev. Balyaslaw Pachopka had prepared a Belarusian grammar using the Latin script. Belarusian linguist S. M. Nyekrashevich considered B. Pachopka's grammar unscientific and ignorant of the principles of the Belarusian language. In 1918, for an unspecified period, the B. Pachopka's grammar was reportedly taught in an unidentified number of schools. Another grammar was, supposedly, jointly prepared by A. Lutskyevich and Ya. Stankyevich, and differed from Tarashkyevich's grammar somewhat in resolution of some key aspects.

1914-1917

On December 22, 1915, Hindenburg issued an order on schooling in German Army occupied territories (of contemp. Russian Empire), banning the schooling in Russian and including the Belarusian language in the exclusive list of the four languages being mandatory in the respective native schooling systems (Belarusian, Lithuanian, Polish, Yiddish). The attending to school wasn't made mandatory, though. The passports in these lands were being issued bi-lingual, in German and in one of the "native languages". [Turonek 1989] The certain numbers of the Belarusian preparatory schools, printing houses, press organs were opened (see also: Homan (1916)).

1917-1920

After the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, the Belarusian language became an unprecedentedly important factor in the political activities in the Belarusian lands (see also: Central Council of Belarusian Organisations, Great Belarusian Council, I All-Belarusian Congress, Belnatskom). In the Belarusian People's Republic, the Belarusian was used as its only official language (decreed by Belarusian People's Secretariat, 1918-04-28). In the Belarusian SSR, the Belarusian was decreed to be one of the four (Belarusian, Polish, Russian, Yiddish) official languages (decreed by Central Executive Committee of BSSR, February 1921).

1920-1930

Soviet Belarus

In BSSR, the Tarashkyevich’s grammar had been officially accepted for use in state schooling after its re-publishing in the unchanged form by Yazep Lyosik under the name «Ya. Lyosik. Practical grammar. P[art]. I» (1922). This grammar had been re-published once again, unchanged, by the Belarusian State Publishing House under the name «Ya. Lyosik. Belarusian language. Grammar. Ed. I. 1923» (1923).

In 1925, Yazep Lyosik introduced two new chapters to the grammar, addressing the orthography of combined words and partly modifying the orthography of assimilated words. Hence, the Belarusian grammar had been popularised and taught in the educational system in that form.

The ambiguousness and insufficient development of several components of Tarashkyevich’s grammar had been the cause of some problems in practical mass usage and stirred a certain discontent with the grammar.

In 1924–1925, Yazep Lyosik and Anton Lyosik prepared and published their project of orthographical reform, proposing a number of radical changes. A fully phonetic orthography was introduced. One of the most distinctive changes brought in was the principle of Akanye (Belarusian: ́аканне), wherein unstressed "o", pronounced in both Russian and Belarusian as [a], is written as "а". Consequently, words like [malaˈko] are pronounced the same in both languages but written as Russian: Молоко in Russian and Малако in Belarusian.

The Belarusian Academic Conference on Reform of the Orthography and Alphabet (1926) had been called, and after discussions on the project the Conference had made resolutions on some of the problems. However, as the project of Lyosik brothers hadn’t been addressing all of the problematic issues, so the Conference hadn’t been able to address all of those, either.

As the outcome of the conference, the Orthographical Commission created to prepare the project of the actual reform was formed on 1927-10-01, headed by S. Nyekrashevich, with the following principal guidelines of its work adopted:

- To consider the resolutions of the Belarusian Academical Conference (1926) non-mandatory, although highly competent material.

- To simplify Tarashkyevich’s grammar where it was ambiguous or difficult in use, to amend it where it was insufficiently developed (e.g., orthography of the assimilated words), and to create new rules if absent (orthography of the proper names and geographical names).

During its work in 1927-1929, the Commission had actually prepared the project of the reform of the orthography. The resulting project had included both completely new rules and existing rules in unchanged and changed forms, with those changed being, variously, the outcome of the work of the Commission itself, or the resolutions of Belarusian Academical Conference (1926), re-approved by the Commission.

Notably, the use of the Ь (soft sign) before the combinations "consonant+iotified vowel" ("softened consonants"), which had been denounced as highly redundant before (e.g., in the proceedings of the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926)), had been cancelled. However, the complete resolition of the highly important issue of the orthography of the un-stressed Е (IE) had not been achieved.

It is worth noticing, that both the resolutions of the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926) and the project of the Orthographical Commission (1930) caused much disagreement in the Belarusian academic environment. Several elements of the project were to be put under appeal in the «higher (political?) bodies of power».

West Belarus

In West Belarus, under Polish rule, the Belarusian language was at a disadvantage. Schooling in the Belarusian language was obstructed, and printing in Belarusian experienced political oppression.

The prestige of the Belarusian language in the Western Belarus of the period hinged significantly on the image of the BSSR being the "true Belarusian home".[18] This image, however, was strongly disrupted by the "purges" of "national-democrats" in BSSR (1929 – 1930) and by the following grammar reform (1933).

Tarashkyevich's grammar was re-published five times in Western Belarus. However, the 5th edition (1929)[19] was the version diverting from the previously published, which Tarashkyevich had prepared disregarding the Belarusian Academic Conference (1926) resolutions.[20]

1930s

Soviet Belarus

In 1929 – 1930, the Communist authorities of the Soviet Belarus had brought out the drastic crackdowns against the supposed «national-democratic counter-revolution» (inf. «nats-dems» (Belarusian: нац-дэмы)). Effectively, the entire generations of the Socialist Belarusian national activists of the 1st quarter of the 20th cent. had been wiped out from the political, scientifical, in fact, from any real social existence. Only the most famous cult figures (e.g. Yanka Kupala) were spared.

However, the new power group in the Belarusian science quickly formed, or, possibly, emerged after the power shifts, under the virtual leadership of the Head of the Philosophy Institute of the Belarusian Academy of Sciences, academician S. Ya. Vol’fson (С. Я. Вольфсон). The book published under his editorship «Science in service of nats-dems’ counter-revolution» (1931), represented the new spirit of the political life in Soviet Belarus.

The Reform of Belarusian Grammar (1933) had been brought out quite unexpectedly, supposedly, [Stank 1936] with the project published in the central newspaper of the Belarusian Communist Party «Zviazda» on 1933-06-28 and the decree of the Council of People’s Commissaries (Council of Ministers) of BSSR issued on 1933-08-28, to gain the status of law on 1933-09-16.

There had been some post-factum speculations, too, that the 1930 project of the reform (as prepared by the people no longer politically «clean»), had been given for the «purification» to the «nats-dems» competition in the Academy of Sciences, which would explain the «block» nature of the differences between the 1930 and 1933 versions. Peculiarly, Yan Stankyevich in his notable critique of the reform [Stank 1936] didn’t mention the project prepared by 1930, dating the project of the reform to 1932.

The officially announced causes for the reform were:

- The pre-1933 grammar was maintaining artificial barriers between the Russian and Belarusian languages.

- The reform was to cancel the influences of the Polonisation corrupting the Belarusian language.

- The reform was to remove the archaisms, neologisms and vulgarisms, supposedly introduced by the «national-democrats».

- The reform was to simplify the grammar of the Belarusian language.

The reform had been accompanied by the fervent press campaign directed against the «nats-dems not yet giving up».

The decree had been named «On changing and simplifying of the Belarusian orthography» («Аб зменах і спрашчэнні беларускага правапісу»), but the bulk of the changes had been introduced into the grammar. Yan Stankyevich in his critique of the reform talked about 25 changes, with 1 of them being strictly orthographical, and 24 relating to both orthography and grammar. [Stank 1936]

It is worth noticing, that many of the changes in the orthography proper («stronger principle of AH-ing», «no redundant soft sign», «uniform ’’nye’’ and ’’byez’’») had been, in fact, just implementations of the earlier propositions of the by then repressed persons (e.g., Yazep Lyosik, Lastowski, Nyekrashevich, 1930 project). [BAC 1926][Nyekr 1930][Padluzhny 2004]

The morphological principle in the orthography had been strengthened, which also had been proposed in 1920s. [BAC 1926]

The «removal of the influences of the Polonisation» had been represented, effectively, by the:

- Reducing the use of the «consonant+non-iotified vowel» in assimilated Latinisms in favour of «consonant+iotified vowel», leaving only «Д», «Т», «Р» unexceptionally «hard».

- Changing the method of representation of the sound «L» in the Latinisms to another variant of the Belarusian sound «Л» (of 4 variants existing), rendered with succeeding non-iotified vowels instead of iotified.

- Introducing the new preferences of use of the letters «Ф» over «Т» for «fita», and «В» over «Б» for «beta», in Hellenisms. [Stank 1936]

The «removing of the artificial barriers between the Russian and Belarusian languages» (virtually the often-quoted «Russification of the Belarusian language», which may well happen to be a term coined by Yan Stankyevich) had, according to Stankyevich, moved the normative Belarusian morphology and syntax closer to their Russian counterparts, often removing from the use the indigenous features of the Belarusian language. [Stank 1936]

Stankyevich also observed that some components of the reform had moved the Belarusian grammar to the grammars of other Slavonic languages, which would hardly be its goal. [Stank 1936]

West Belarus

In West Belarus, there had been some voices raised against the reform, chiefly by the non-Communist/non-Socialist wing of the Belarusian national scena. Yan Stankyevich named Belarusian Scientific Society, Belarusian National Committee, Society of the friends of Belarusian linguistics in the Wilno University. [Stank 1936] Certain political and scientifical groups and figures went on with using the pre-reform orthography and grammar, however, in succeedingly multiplying and differing versions.

However, the reformed grammar and orthography had been used, too, e.g., during the process of S. Prytytski (1936).

Second World War

In times of Occupation of Belarus by Nazi Germany (1941–1944), the Belarusian collaborants used the Belarusian language, in the press and schools which were influenced by them, in the Belarusian language variant, which was deliberately rejecting all post-1933 changes in vocabulary, orthography and grammar. Much publishing in Belarusian Latin script was done.

Otherwise, including but not limited to the publications of Soviet partisan movement in Belarus, the normative 1934 grammar was used.

Post Second World War

After the World War, several major factors influenced the development of the Belarusian language. The most important was the implementation of "rapprochment and unification of Soviet people" policy which resulted in Russian language by 1980s effectively and officially assuming the role of principal mean of communication, with Belarusian relegated to a secondary role. The post-war growth of circulation of publishing in Belarusian in BSSR drastically lagged behind those in Russian. The use of Belarusian as main language of education was gradually limited to rural schools and humanitarian faculties[21]. While officially much lauded, the language was popularly imaged as "uncultured, rural language of rural people".

That was the source of concern for the nationally minded and caused, e.g., the series of publications by Barys Sachanka in 1957–1961 and the text named "Letter to Russian friend" by Alyaksyey Kawka (1979). Interestingly, the contemporary BSSR Communist party leader Kirill Mazurov made some tentative moves to strengthen the role of Belarusian language in the 2nd half 1950s[22]. However, the support of the Belarusian could also be easily considered "too strong" and even identified with the support of "Belarusian nationalists and fascists".

After the beginning of Perestroika and relaxing of the political control in end 1980s, the new campaign in support of the Belarusian language was mounted in BSSR, expressed in "Letter of 58" and other publications, producing certain level of popular support and resulting in the BSSR Supreme Soviet ratifying the "Law on languages" ("Закон аб мовах"; January 26 1990) mandating the strengthening of the role of Belarusian in the state and civic structures.

Reform of grammar in 1959

In 1949–1957, the discussion on problems of the Belarusian orthography and on the further development of language, started in 1935–1941, was continued, and the need to amend some unwarranted changes, introduced in the 1933 reform, was expressed. The Orthography Commission, headed by Yakub Kolas, had the project prepared about 1951, but the project was approved only in 1957, and the normative rules were published in 1959[23]. This grammar is the normative for Belarusian language since then, receiving minor practical changes in 1985 edition.

In 2006–2007, the project of corrections and of parts of the 1959 grammar was being discussed.

Post 1991

After the Belarusian independence, the Belarusian language gained much prestige and popular interest. However, the implementation of the "Law on languages" in 1992–1994 was done in such way, that it provoked public protests and was dubbed "Landslide Belarusization" and "undemocratical" by forces opposing. In the referendum held on May 14 1995 the Belarusian language lost its exclusive status of the only state language. The state support of the Belarusian language and culture in general dwindled since then.

Tarashkevitsa

The legitimacy of the reform of grammar in 1933 was never adopted by certain political groups in West Belarus, unlike, e.g., KPZB, and also by the emigrants, who left Belarus after 1944.where this rejection was made an issue of ideology, and presented as anti-Russification[24]. One of the most vocal critics was Yan Stankyevich, beginning with his 1936 publication.

However, rejecting all post-1933 official developments, the community was left with all the problems of the pre-1933 grammar virtually unaddressed (cf. the materials of Society for the Cleanliness of Belarusian language, Prague, 1930s-1940s) and effectively with no unified grammar to use (cf. the discussion between Yan Stankyevich and Masyey Syadnyow in beg.1950s, the policy of Bats'kawshchyna printing house etc.).

It is worth noting that with the Belarusian schools in Poland closed in 1937, the only wide-scale use of the pre-1933 grammar after the 1930s took place during the German occupation of Belarus in 1941–1944.

The important issue is the certain ambiguity of the Belarusian word "pravapis" which in non-academic use may refer either to just orthography or to the other branches of grammar (e.g., morphology) in general.

In the Perestroika period of the end 1980s, the movement for the returning of "true" language was initiated, meaning the further unprecised "cancellment" of the effects of the 1933 reform. Several periodicals, chiefly of Belarusian People's Front side of political spectrum, Svaboda, Pahonya, Naša Niva, began to be issued in beg.1990s in the grammar with several issues of the Belarusian orthography and grammar used in the pre-1933 form, notably "issue of soft sign", "westernized Latinisms", "westernized hellenisms".

Generally, the ban on the publishing in non-normative grammar was lifted, too.

There was no unified approach between the editors as to what set of grammar and lexics features to use, although calls to unification were made, principally by Vincuk Viačorka (cf. publications in journal Spadchyna in 1991 and 1994, project of "revised classic orthography" in 1995, ibid).

The orthography (or, actually, grammar, as pointed out in the issue of word pravapis) with such features was dubbed "tarashkevitsa" in such editions, emphasising its closer relation to the 1918 work of Tarashkyevich. These editions started to refer to it as "classic" since c. 1994 (notably, in 1994 article by Vincuk Viačorka).

On the other hand, any post-1933 official grammar was derogatory dubbed "narkamauka" in the press of that persuasion, emphasising grammar's origin in People Commisariat ("narkamat" – Ministry).

Generally, the issue created a schism in the Belarusian-speaking community, opinions varying from wholesale approval to likewise rejection, with notable expression in the 1992–1993 discussion in the newspaper "Nasha slova", published then by Frantsishak Skaryna Belarusian Language Society, or in the 2003 questionnaire in the journal ARCHE.

Major editions of Belarusian minority in eastern Poland, like newspaper Niva, did not take sides in the issue, and continued to use normative variant of language.

There was certain amount of lobbying in 1992–1993 to enact the retro-changes in orthography through the state authorities decision. The Civic Commission on the Orthography was called as result, with mission of providing the recommendation on that matter. The recommendation of the Commission (September 13 1994) said that while partial return of some of the pre-1933 rules could indeed be plausible, the time for such changes is not yet appropriate.

After the 1994, the promoters of the alternative ("classic") grammar continued the publishing and work on the internal codification based on the Viačorka project.

Some of the editions targeting the popular audience, like newspapers Svaboda (Minsk) and Pahonya (Hrodna), switched to the normative variant of Belarusian later.

2005 proposal

In the 2005 the working group of four persons produced the "Classic orthography. Modern normalisation" being the attempt on the internal standard. One of the prominent features is changed alphabet (the extra letter added).

This proposal was adopted by such major Tarashkevitsa-using media, as the newspaper Naša Niva, the Belarusian editions of Radio Free Europe and Radio Polonia. The adoption status in the other supporting groups, like other publishing houses or Belarusian USA diaspora, is uncertain.

Computer representation

Belarusian is represented by the ISO 639 code be or bel, or more specifically by IETF language tags be-1959acad ("Academic" ["governmental"] variant of Belarusian as codified in 1959) or be-tarask (Belarusian in Taraskievica orthography).[1]

Notes

- ↑ Also spoken in Azerbaijan, Canada, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, USA, Uzbekistan, per Ethnologue.

- ↑ Of these, about 3,370,000 (41.3%) are Belarusians, and about 257,000 belong to other major nationalities (Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, Jews).

- ↑ Data from 1999 Belarusian general census In English.

- ↑ (Johnstone and Mandryk 2001) as cited on Ethnologue.

- ↑ In Russia, the Belarusian language is declared as a "familiar language" by about 316,000 inhabitants, among them, about 248,000 Belarusians, which comprise about 30.7% of Belarusians living in Russia (data from 2002 Russian general census In Russian). In Ukraine, the Belarusian language is declared as a "native language" by about 55,000 Belarusians, which comprise about 19.7% of Belarusians living in Ukraine (data from 2001 Ukrainian census In Ukrainian). In Poland, the Belarusian language is declared as a "language spoken at home" by about 40,000 inhabitants (data from 2002 Polish general census Table 34 (in Polish)).

- ↑ Section One of the Constitution, Webportal of the President of the Republic of Belarus , Published 1994, amended in 1996. Retrieved June 07, 2007.

- ↑ Acc. to: Улащик Н. Введение в белорусско-литовское летописание. – М., 1980.

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926] Ch. XVII Sec.1

- ↑ [Turuk 1921], p.10

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926] Ch. XXII Sec.1 p.507

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926] Ch. XV Sect. 10.

- ↑ Per (Dovnar 1926), (Smalyanchuk 2001)

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926] Ch. XV Sect. 7

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926]. Ch. XV. Sect.3.

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926] Ch. XV Sect. 4.

- ↑ [Turuk 1921], p.11

- ↑ [Dovnar 1926] Ch. XXI Sec.4 p.480-481

- ↑ (words of V. Lastouski)

- ↑ Re-printed verbatim in Belarus (1991) and often referenced to.

- ↑ [Tarashk 1929] Foreword.

- ↑ The BSSR counterpart of the USSR law «On strengthening of ties of school with real life and on further development of the popular education in USSR» (1958), adopted in 1959, along with introduction of the mandatory 8-year school education, made it possible for the parents of pupils to opt for non-mandatory studying of the «second language of teaching», which would be Belarusian in Russian language school and vice versa. However, e.g., in 1955/1956 schooling year there had been 95% of schools with Russian as the primary language of teaching, and 5% with Belarusian as the primary language of teaching. [StStank 1962]

- ↑ See Modern history of Belarus by Mironowicz.

- ↑ The BSSR Council of Ministers approved the project of the Commission on Orthography «On making more precise and on partially changing the acting rules of Belarusian orthography» («Аб удакладненні і частковых зменах існуючага беларускага правапісу») on 1957-05-11. The project had served as a basis for the normative «Rules of the Belarusian orthography and punctuation» («Правілы беларускай арфаграфіі і пунктуацыі»), published in 1959.

- ↑ E.g., per Jerzy Turonek, Belarusian book under German control (1939-1944) (in edition: Юры Туронак, Беларуская кніга пад нямецкім кантролем, Minsk, 2002).

References

- [Karsk 1893] Карский Е. Ф. Что такое древнее западнорусское наречие? // «Труды Девятого археологического съезда в Вильне, 1893», под ред. графини Уваровой и С. С. Слуцкого, т. II – М., 1897. – с. 62 – 70. In edition: Карский Е. Ф. Белорусы: 3 т. Т. 1 / Е. Ф. Карский / Уступны артыкул М. Г. Булахава, прадмова да першага тома і каментарыі В. М. Курцовай, А. У. Унучака, І. У. Чаквіна . – Мн. : БелЭн, 2006. – с. 495 – 504. ISBN 985-11-0360-8 (T.1), ISBN 985-11-0359-4.

- [Karsk 1903] Карский, Е. Ф. Белорусы: 3 т. Т. 1 / Уступны артыкул М. Г. Булахава, прадмова да першага тома і каментарыі В. М. Курцовай, А. У. Унучака, І. У. Чаквіна. ; [Карскій. Бѣлоруссы. Т. I – Вильна, 1903] – Мн. : БелЭн, 2006. ISBN 985-11-0360-8 (Т.1), ISBN 985-11-0359-4.

- [Lyosik 1917] [Язэп Лёсік] Граматыка і родная мова : [Вольная Беларусь №17, 30.08.1917] // Язэп Лёсік. Творы: Апавяданні. Казкі. Артыкулы / (Уклад., прадм. і камент. А. Жынкіна. – Мн. : Маст. літ., 1994. – (Спадчына). ISBN 5-340-01250-6.

- [Stank 1939] Ян Станкевіч. Гісторыя беларускага языка [1939] // Ян Станкевіч. Збор твораў у двух тамах. Т. 1. - Мн.: Энцыклапедыкс, 2002. ISBN 985-6599-46-6.

- [StStank 1962] Станкевіч С. Русіфікацыя беларускае мовы ў БССР і супраціў русіфікацыйнаму працэсу [1962] / Прадмова В. Вячоркі. – Мн. : Навука і тэхніка, 1994. ISBN 5-343-01645-6.

- [Zhur 1978] А. И. Журавский. Деловая письменность в системе старобелорусского литературного языка // Восточнославянское и общее языкознание. – М., 1978. – С. 185-191.

- [Halyen 1988] Галенчанка Г. Я. Кнігадрукаванне ў Польшчы // Францыск Скарына і яго час. Энцыклапед. даведнік. – Мн. : БелЭн, 1988. ISBN 5-85700-003-3.

- [AniZhur 1988] Анічэнка У. В., Жураўскі А. І. Беларуская лексіка ў выданнях Ф. Скарыны // Францыск Скарына і яго час. Энцыклапед. даведнік. – Мн. : БелЭн, 1988. ISBN 5-85700-003-3.

- [Zhur 1993] Жураўскі А. І. Беларуская мова // Энцыклапедыя гісторыі Беларусі. У 6 т. Т. 1. - Мн.: БелЭн, 1993.

- [Yask 2001] Яскевіч А. А. Старабеларускія граматыкі: да праблемы агульнафілалагічнай цэласнасці. – 2-е выд. – Мн. : Беларуская навука, 2001. ISBN 985-08-0451-3.

- [Lis 1991] Браніслаў Тарашкевіч. Выбранае: Крытыка, публіцыстыка, пераклады / Укладанне, уступ, камент. А. Ліса. – Мн. : Маст. літ., 1991. – (Спадчына). ISBN-5-340-00498-8

- [Lis 1966] Арсень Ліс. Браніслаў Тарашкевіч – Мн. : Навука і Тэхніка, 1966.

- [BAC 1926] Да рэформы беларускага правапісу. // Пасяджэньні Беларускае Акадэмічнае Конфэрэнцыі па рэформе правапісу і азбукі. - Мн.: [б. м.], [1927?].

- [Tarashk 1929] Б. Тарашкевіч. Беларуская граматыка для школ. - Вільня : Беларуская друкарня ім. Фр. Скарыны, 1929 ; Мн. : «Народная асвета», 1991 [факсімільн.]. - Выданьне пятае пераробленае і пашыранае.

- [Stank 1918] Ян Станкевіч. Правапіс і граматыка [1918] // Ян Станкевіч. Збор твораў у двух тамах. Т. 1. - Мн.: Энцыклапедыкс, 2002. ISBN 985-6599-46-6

- [Stank 1927] Ян Станкевіч. Беларуская Акадэмічная Конфэрэнцыя 14.–21.XI.1926 і яе працы дзеля рэформы беларускае абэцэды й правапісу (агульны агляд) [1927] // Ян Станкевіч. Збор твораў у двух тамах. Т. 1. - Мн.: Энцыклапедыкс, 2002. ISBN 985-6599-46-6

- [Stank 1930] Ян Станкевіч. Б. Тарашкевіч: Беларуская граматыка для школ. Выданьне пятае пераробленае і пашыранае. Вільня. 1929 г., бал. 132 + IV [1930–1931] // Ян Станкевіч. Збор твораў у двух тамах. Т. 1. - Мн.: Энцыклапедыкс, 2002. ISBN 985-6599-46-6

- [Baranowski 2004] Ігар Бараноўскі. Помнік сьвятару-беларусу (120-ыя ўгодкі з дня нараджэньня а. Баляслава Пачопкі) // Царква. Грэка-каталіцкая газета. № 4 (43), 2004. – Брэст: ПП В.Ю.А., 2004.

See also

- Old Ruthenian language

- East Slavic languages

- Kievan Rus'

- Ruthenia

- Narkamauka

- Trasianka, a blend of Russian and Belarusian languages spoken by many in Belarus

- Swadesh list of Belarusian words

External links

- Ethnologue report for Belarusian

- English-Belarusian dictionaries, in Lacinka

- (Belarusian) Łacinka.org

- Metrica of GDL

- Statutes of GDL

- (Belarusian) pravapis.org - Belarusian language

- Fundamentals of Modern Belarusian

- Belarusan English Dictionary from Webster's Online Dictionary - the Rosetta Edition

- A short Belarusian-English-Japanese Phrasebook(Renewal) incl. sound file

|

|||||||||||||||||