Symphony No. 9 (Beethoven)

The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 "Choral" is the last complete symphony composed by Ludwig van Beethoven. Completed in 1824, the choral Ninth Symphony is one of the best known works of the Western repertoire, considered both an icon and a forefather of Romantic music, and one of Beethoven's greatest masterpieces.

Symphony No. 9 incorporates part of An die Freude ("Ode to Joy"), a poem by Friedrich Schiller written in 1785 (first published in 1786 in the poet's own literary journal, Thalia), with text sung by soloists and a chorus in the last movement. It is the first example of a major composer using the human voice on the same level with instruments in a symphony, creating a work of a grand scope that set the tone for the Romantic symphonic form.

Beethoven's Symphony No. 9 plays a prominent cultural role in the world today. In particular, the music from the fourth movement (Ode to Joy) was rearranged by Herbert von Karajan into what is now called the Anthem of Europe. Further testament to its prominence is that an original manuscript of this work sold in 2003 for $3.3 million USD at Sotheby's, London. Stephen Roe, the head of Sotheby's manuscripts department, described the symphony as "one of the highest achievements of man, ranking alongside Shakespeare's Hamlet and King Lear."

Contents |

History

Composition

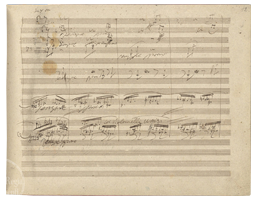

The Philharmonic Society of London originally commissioned the symphony in 1817. Beethoven started work on his last symphony in 1818 and finished it early in 1824. This was roughly twelve years after his eighth symphony. However, he was interested in the Ode to Joy from a much earlier time, having set it to music as early as 1793; that setting is lost.

The theme for the scherzo can be traced back to a fugue written in 1815. The introduction for the vocal part of the symphony caused many difficulties for Beethoven. It was the first time he—or anyone—had used a vocal component in a symphony. Beethoven's friend, Anton Schindler, later said: "When he started working on the fourth movement the struggle began as never before. The aim was to find an appropriate way of introducing Schiller's ode. One day he [Beethoven] entered the room and shouted 'I got it, I just got it!' Then he showed me a sketchbook with the words 'let us sing the ode of the immortal Schiller'". However, that introduction did not make it into the work, and Beethoven spent a great deal of time rewriting the part until it had reached the form recognizable today.

Premiere

Beethoven was eager to have his work played in Berlin as soon as possible after finishing it. He thought that musical taste in Vienna was dominated by Italian composers such as Rossini. When his friends and financiers heard this, they urged him to premiere the symphony in Vienna.

The Ninth Symphony was premiered on May 7 1824 in the Kärntnertortheater in Vienna, along with the overture Die Weihe des Hauses and the first three parts of the Missa Solemnis. This was the composer's first on-stage appearance in twelve years; the hall was packed. The soprano and alto parts were interpreted by two famous young singers: Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger.

Although the performance was officially directed by Michael Umlauf, the theatre's Kapellmeister, Beethoven shared the stage with him. However, two years earlier, Umlauf had watched as the composer's attempt to conduct a dress rehearsal of his opera Fidelio ended in disaster. So this time, he instructed the singers and musicians to ignore the totally deaf Beethoven. At the beginning of every part, Beethoven, who sat by the stage, gave the tempos. He was turning the pages of his score and was beating time for an orchestra he could not hear.

There are a number of anecdotes about the premiere of the Ninth. Based on the testimony of the participants, there are suggestions that it was under-rehearsed (there were only two full rehearsals) and rather scrappy in execution. On the other hand, the premiere was a big success. In any case, Beethoven was not to blame, as violist Josef Bohm recalled, "Beethoven directed the piece himself; that is, he stood before the lectern and gesticulated furiously. At times he raised, at other times he shrunk to the ground, he moved as if he wanted to play all the instruments himself and sing for the whole chorus. All the musicians minded his rhythm alone while playing".

When the audience applauded - testimonies differ over whether at the end of the scherzo or the whole symphony - Beethoven was several measures off and still conducting. Because of that, the contralto Caroline Unger walked over and turned Beethoven around to accept the audience's cheers and applause. According to one witness, "the public received the musical hero with the utmost respect and sympathy, listened to his wonderful, gigantic creations with the most absorbed attention and broke out in jubilant applause, often during sections, and repeatedly at the end of them." The whole audience acclaimed him through standing ovations five times; there were handkerchiefs in the air, hats, raised hands, so that Beethoven, who could not hear the applause, could at least see the ovation gestures. The theatre house had never seen such enthusiasm in applause.

At that time, it was customary that the Imperial couple be greeted with three ovations when they entered the hall. The fact that five ovations were received by a private person who was not even employed by the state, and moreover, was a musician (a class of people who had been perceived as lackeys at court), was in itself considered almost indecent. Police agents present at the concert had to break off this spontaneous explosion of ovations. Beethoven left the concert deeply moved.

The repeat performance on May 23 in the great hall of the Fort was, however, poorly attended.

Editions

The Breitkopf & Härtel edition dating from 1864 has been used widely by orchestras.[1] In 1997 Bärenreiter published an edition by Jonathan Del Mar[2]. According to Del Mar, this edition corrects nearly 3000 mistakes in the Breitkopf edition, some of which were remarkable.[3] Professor David Levy, however, criticized this edition in Beethoven Forum, saying that it could create "quite possibly false" traditions.[4] Breitkopf also published a new edition by Peter Hauschild in 2005.[5]

While many of the modifications in the newer editions make minor alterations to dynamics and articulation, both editions make a major change to the orchestral lead-in to the final statement of the choral theme in the fourth movement (IV: m525-m542). The newer versions alter the articulation of the horn calls, creating syncopation that no longer relates to the previous motive. The new Breitkopf & Härtel and Bärenreiter make this alteration differently, but the result is a reading that is strikingly different than what was commonly accepted based on the 1864 Breitkopf edition. While both Breitkopf & Härtel and Bärenreiter consider their editions the most accurate versions available--labeling them Urtext editions--their conclusions are not universally accepted. In his monograph "Beethoven--the ninth symphony", Professor David Levy describes the rationale for these changes and the danger of calling the editions Urtext.

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for the following orchestra. These are by far the largest forces needed for any Beethoven symphony; at the premiere, Beethoven augmented them further by assigning two players to each wind part.

|

(all voices fourth movement only)

|

Form

The symphony is in four movements, marked as follows:

- Allegro ma non troppo, un poco maestoso

- Scherzo: Molto vivace - Presto

- Adagio molto e cantabile - Andante Moderato - Tempo I - Andante Moderato - Adagio - Lo Stesso Tempo

- Recitative: (Presto – Allegro ma non troppo – Vivace – Adagio cantabile – Allegro assai – Presto: O Freunde) – Allegro assai: Freude, schöner Götterfunken – Alla marcia – Allegro assai vivace: Froh, wie seine Sonnen – Andante maestoso: Seid umschlungen, Millionen! – Adagio ma non troppo, ma divoto: Ihr, stürzt nieder – Allegro energico, sempre ben marcato: (Freude, schöner Götterfunken – Seid umschlungen, Millionen!) – Allegro ma non tanto: Freude, Tochter aus Elysium! – Prestissimo: Seid umschlungen, Millionen!

Beethoven changes the usual pattern of Classical symphonies in placing the scherzo movement before the slow movement (in symphonies, slow movements are usually placed before scherzos). This was the first time that he did this in a symphony, although he had done so in some previous works (including the quartets Op. 18 no. 5, the "Archduke" piano trio Op. 97, the "Hammerklavier" piano sonata Op. 106). Haydn, too, had used this arrangement in a number of works.

First movement

The first movement is in sonata form, and the mood is often stormy. The opening theme is played pianissimo over string tremolos. This first subject later returns fortissimo at the outset of the recapitulation section, in D major, rather than the opening's D minor. The coda employs the chromatic fourth interval.

Second movement

The second movement, a scherzo, is also in D minor, with the opening theme bearing a passing resemblance to the opening theme of the first movement, a pattern also found in the Hammerklavier piano sonata, written a few years earlier. It uses propulsive rhythms and a timpani solo. At times during the piece Beethoven directs that the beat should be one downbeat every three bars, perhaps because of the very fast pace of the majority of the movement which is written in triple time, with the direction ritmo di tre battute ("rhythm of three bars"), and one beat every four bars with the direction ritmo di quattro battute ("rhythm of four bars").

Beethoven had been criticised before for failing to adhere to standard form for his compositions. He used this movement to answer his critics. Normally, Scherzos are written in triple time. Beethoven wrote this piece in triple time, but it is punctuated in a way that, when coupled with the speed of the metre, makes it sound as though it is in quadruple time.

The contrasting trio section is in D major and in duple (cut) time. The trio is the first time the trombones play in the work.

Third movement

The lyrical slow movement, in B flat major, is in a loose variation form, with each pair of variations progressively elaborating the rhythm and melody. The first variation, like the theme, is in 4/4 time, the second in 12/8. The variations are separated by passages in 3/4, the first in D major, the second in G major. The final variation is twice interrupted by episodes in which loud fanfares for the full orchestra are answered by double-stopped octaves played by the first violins alone. A prominent horn solo is assigned to the fourth player. Trombones are tacet for the movement.

Fourth movement

The famous choral finale is Beethoven's musical representation of Universal Brotherhood and has been characterized by Charles Rosen as a symphony within a symphony. It contains four movements played without interruption.[6] This "inner symphony" follows the same overall pattern as the Ninth Symphony as a whole. The scheme is as follows:

- First "movement": theme and variations with slow introduction. Main theme which first appears in the cellos and basses is later "recapitulated" with voices.

- Second "movement": 6/8 scherzo in military style (begins at "Alla marcia," words "Froh, wie seine Sonnen fliegen"), in the "Turkish style." Concludes with 6/8 variation of the main theme with chorus.

- Third "movement": slow meditation with a new theme on the text "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" (begins at "Andante maestoso")

- Fourth "movement": fugato finale on the themes of the first and third "movements" (begins at "Allegro energico")

The movement has a thematic unity, in which every part may be shown to be based on either the main theme, the "Seid umschlungen" theme, or some combination of the two.

The first "movement within a movement" itself is organized into sections:

- An introduction, which starts with a stormy Presto passage. It then briefly quotes all three of the previous movements in order, each dismissed by the cellos and basses which then play in an instrumental foreshadowing of the vocal recitative. At the introduction of the main theme, the cellos and basses take it up and play it through.

- The main theme forms the basis of a series of variations for orchestra alone.

- The introduction is then repeated from the Presto passage, this time with the bass soloist singing the recitatives previously suggested by cellos and basses.

- The main theme again undergoes variations, this time for vocal soloists and chorus.

Vocal parts

Words written by Beethoven (not Schiller) are shown in italics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Influence

The Ninth Symphony struck the changing and newly Romantic world of Western music with force. Partially due to the scope, ambition, and import of this work, Beethoven is considered the forefather of Romantic music. His Symphony No. 9 was to prove extremely influential on the Western tradition, not just in specific compositional form (and length), but in much more general ways, for its forging of new ground beyond the Classical symphonic mould of purely "absolute music". It is an early icon and declaration of the Romantic idealistic tradition of Bildung.

Many later composers of the Romantic period and beyond were influenced specifically by Beethoven's final symphony:

At Easter 1831 Richard Wagner completed a piano arrangement of Beethoven's 9th symphony. Wagner had to decide which instrumental lines in the original had to be omitted since the pianist cannot play all the orchestral parts, thus giving his reduction a personal signature.

An important theme in the finale of Johannes Brahms' Symphony No. 1 in C minor is related to the "Ode to Joy" theme from the last movement of Beethoven's Ninth symphony. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he is reputed to have retorted "Any ass can see that!", which suggests the imitation was intentional. Brahms's first symphony was, at times, both praised and derided as "Beethoven's Tenth".[8]

Anton Bruckner used the chromatic fourth in his third symphony in much the same way that Beethoven used it in the first movement's coda.

In the opening notes of the third movement of his Symphony No. 9 (The "New World"), Antonín Dvořák pays homage to the scherzo of this symphony with his falling fourths and timpani strokes.[9]

The hymn, "Joyful, Joyful We Adore Thee", with words written in 1907 by Henry Van Dyke, is sung to the "Ode to Joy" tune and is included in many hymnals.

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony may also have influenced the development of the compact disc. Philips, the company that had started the work on the new audio format, originally planned for a CD to have a diameter of 11.5 cm, while Sony planned a 10 cm diameter needed for one hour of music. However, according to a Philips website, Norio Ohga insisted in 1979 that the CD be able to contain a complete performance of the Ninth Symphony:

| “ | The longest known performance lasted 74 minutes. This was a mono recording made during the Bayreuther Festspiele in 1951 and conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler. This therefore became the playing time of a CD. A diameter of 12 centimeters was required for this playing time.[10] | ” |

However, Kees Immink, Philips' chief engineer, who developed the CD, denies this, claiming that the increase was motivated by technical considerations, and that even after the increase in size, the Furtwängler recording was not able to fit onto the earliest CDs.[11]

Curse of the ninth

Using modern numbering, several composers besides Beethoven have completed no more than nine symphonies. This has led certain subsequent composers, particularly Gustav Mahler, to be superstitious about composing their own ninth or tenth symphonies, or to try to avoid writing them at all. This phenomenon has become known as the "curse of the ninth".

Performance challenges

Duration

Lasting more than an hour, the Ninth was an exceptionally long symphony for its time. Like much of Beethoven's later music, his Ninth Symphony is demanding for all the performers, including the choir and soloists.

Metronome markings

As with all of his symphonies, Beethoven has provided his own metronome markings for the Ninth Symphony, and as with all of his metronome markings, there is controversy among conductors regarding the degree to which they should be followed. Historically, conductors have tended to take a slower tempo than Beethoven marked for the slow movement, and a faster tempo for the military march section of the finale. Conductors in the historically informed performance movement, notably Roger Norrington, have used Beethoven's suggested tempos, to mixed reviews.

Ritard/a tempo at the end of the first movement

Many conductors move the "a tempo" in m.511 of the first movement to measure m.513 to coincide with the "Funeral March".

Re-orchestrations and alterations

A number of conductors have made alterations in the instrumentation of the symphony.

Mahler's Retouching

Gustav Mahler revised the orchestration of the Ninth to make it sound like what he believed Beethoven would have wanted if given a modern orchestra. For example, since the modern orchestra has larger string sections than in Beethoven's time, Mahler doubled various wind and brass parts to preserve the balance between strings on the one hand and winds and brass on the other.

Horn and trumpet alterations

Beethoven's writing for horns and trumpets throughout the symphony (mostly the 2nd horn and 2nd trumpet) is often altered by performers to avoid large leaps (those of a 12th or more).

Flute and first violin alterations

In the first movement, at times the first violins and flute have ascending 7th leaps within mostly descending melodic phrases. Many conductors alter the register of these passages to create a single descending scale (examples: m143 in the flute, m501 in the first violins).

2nd bassoon doubling basses in the finale

Beethoven's indication that the 2nd bassoon should double the basses in measures 115-164 of the finale was not included in the Breitkopf parts, though it was included in the score.

Notable recordings

- Felix Weingartner conducting the London Symphony Orchestra in 1926.

- Oskar Fried conducting the Berlin State Opera Orchestra in 1929.

- Felix Weingartner conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in 1935.

- Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1938 at Carnegie Hall live.

- Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in March 1942.

- Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic on April 19th, 1942, on the eve of Hitler's 53rd birthday. (semi-private recording)

- Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra in 1951. This concert reopened the Bayreuth Festival after the Allies temporarily suspended it following the Second World War.

- Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1952. Robert Shaw, Toscanini's regular assistant, was chorusmaster.

- Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in Lucerne in 1954.

- Otto Klemperer conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra in November 1957. Released by BBC Testament.

- Ferenc Fricsay conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1958, the first stereo recording of the 9th.

- Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1962, 1977 and 1983, as part of complete Beethoven symphony cycles.

- George Szell conducting the Cleveland Orchestra. Recorded in 1961 and released on CD in 1991 by Sony.

- Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Recorded in 1967 and released on CD in 1990 by Sony.

- Rafael Kubelík conducting the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Recorded in 1975 and released on CD by Deutsche Grammophon

- Karl Böhm conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in 1981 with Jessye Norman and Plácido Domingo among the soloists. At 79 minutes, this is among the longest ninths recorded.

- Robert Shaw conducting the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and chorus. Recorded in 1985.

- Günter Wand conducting the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra. Recorded in 1986 and released in 2001 by RCA Red Seal.

- Leonard Bernstein conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. Recorded in 1979 and released in 1980 by Deutsche Grammophon as part of his Vienna Philharmonic cycle of Beethoven symphonies. Bernstein also conducted a version of the 9th, with "Freiheit" ("Freedom") replacing "Freude" ("Joy"), to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall during Christmas 1989. This concert was performed by an orchestra and chorus made up of many nationalities: from Germany, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, the Chorus of the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and members of the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden; from the Soviet Union, members of the Orchestra of the Kirov Theatre, from the United Kingdom, members of the London Symphony Orchestra; from the USA, members of the New York Philharmonic, and from France, members of the Orchestre de Paris. Soloists were June Anderson, soprano, Sarah Walker, mezzo-soprano, Klaus König, tenor, and Jan-Hendrik Rootering, bass.[12]

- Roger Norrington conducting the London Classical Players. Recorded with period instruments. Released in 1987 by EMI Records (rereleased in 1997 under the Virgin Classics label).

- Sir Charles Mackerras recorded the Ninth as the first symphony in his EMI cycle of the Beethoven symphonies with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir in 1991. His soloists included Bryn Terfel, Della Jones, Joan Rodgers and Peter Bronder. This version was among the first to incorporate many of Jonathan Del Mar's corrections. Mackerras later re-recorded the Ninth for his second recorded cycle of Beethoven symphonies for Hyperion Records, live at the 2006 Edinburgh Festival, this time with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

- Benjamin Zander made a 1992 recording of the Ninth with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra and noted soprano Dominique Labelle (who first performed the work with the late Robert Shaw), following Beethoven's own metronome markings.

- Sir John Eliot Gardiner recorded his period-instrument version of the Ninth Symphony, conducting his Monteverdi Choir and Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique in 1992. It was first released by Deutsche Grammophon in 1994 on their early music Archiv Produktion label as part of his complete cycle of the Beethoven symphonies. His soloists included Luba Orgonasova, Anne Sofie von Otter, Anthony Rolfe Johnson and Gilles Cachemaille.

- David Zinman's 1997 recording with the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra was a modern instrument recording that used the Baerenreiter edition edited by Jonathan Del Mar.

- Philippe Herreweghe recorded the Ninth with his period-instrument Orchestre des Champs-Élysées and his Collegium Vocale chorus for Harmonia Mundi in 1999.

- Philadelphia Orchestra and The Westminster Choir with Riccardo Muti in 1988 with Cheryl Studer (soprano), Delores Ziegler (mezzo-soprano), Peter Seiffert, James Morris (bass)

- Seiji Ozawa conducting the Nagano Winter Orchestra as well as seven choirs in six countries on five continents, performed the Fourth Movement in its entirety, for the 1998 Winter Olympic Games during the finale of the Opening Ceremony. The chorus locations being New York City, Berlin, Cape Point, Sydney, and Beijing, with two in Nagano: the Tokyo Opera Singers and the audience at Nagano Olympic Stadium.

- Sir Simon Rattle conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Recorded in 2002 as part of the complete Beethoven symphony cycle on EMI Classics.

- Claudio Abbado conducting the Berliner Philharmoniker. Recorded in 2000 on Deutsche Grammophon with Thomas Quastoff, Thomas Moser, Karita mattila, Violeta Urmana and the Swedish Radio Choir and Eric Ericson Chamber Choir.

- Daniel Barenboim, who had recorded the work twice before, conducting the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra (a youth orchestra of Israel and Arab musicians, which he co-founded) in concert in Berlin on 27 August, 2006

- Bernard Haitink conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. Recorded in April 2006 as part of the complete Beethoven symphony cycle on LSO Live. These recordings are noted for the orchestra's flawless performances. Bernard Haitink's Beethoven Symphony cycle has been nominated for Best Classical Album at the 2007 Grammy Awards.

- Osmo Vänskä conducting the Minnesota Orchestra as part of an ongoing Beethoven symphonies complete set. Nominated for a Grammy Award in 2007.

- Noriko Ogawa's performance of Richard Wagner's arrangement of Symphony No 9 for piano, soloists and choir, with Bach Collegium Japan directed by Masaaki Suzuki

Anthem

During the division of Germany in the Cold War, the Ode to Joy segment of the symphony was also played in lieu of an anthem at the Olympic Games for the Unified Team of Germany between 1956 and 1968. In 1972, the musical backing (without the words) was adopted as the Anthem of Europe by the Council of Europe and subsequently by the European Communities (now the European Union) in 1985.[13] In 1985, the European Union chose Beethoven's music as the EU anthem.[14] When Kosovo declared independence in 2008, it lacked an anthem, so for the independence ceremonies it used Ode to Joy, in recognition of the European Union's role in its independence. It has since adopted its own anthem. Additionally, the Ode to Joy was adopted as the national anthem of Rhodesia in 1974 as Rise O Voices of Rhodesia.

Bibliography

Scholarly

- Richard Taruskin, "Resisting the Ninth", in his Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance (Oxford University Press, 1995).

- James Parsons, “‘Deine Zauber binden wieder’: Beethoven, Schiller, and the Joyous Reconciliation of Opposites,” Beethoven Forum (2002) 9/1, 1-53.

- David Benjamin Levy, "Beethoven: the Ninth Symphony," revised edition (Yale University Press, 2003).

- Esteban Buch, Beethoven's Ninth: A Political History Translated by Richard Miller, ISBN 0-226-07824-8 (University Of Chicago Press)[15]

Literary

- A Clockwork Orange, written by Anthony Burgess, published in 1962 by William Heinemann ISBN 0-434-09800-0

External links

Audio

- CBC Radio Two "Concerts On Demand" (Performance of the entire symphony by Vancouver Symphony Orchestra conducted by Bramwell Tovey)

- David Bernard conducting the Park Avenue Chamber Symphony

- Christoph Eschenbach conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra

- Sound samples and other info from the Classical Music Pages

Scores, manuscripts and text

- Schott Musik International 31st and last publisher of Beethoven & copyright holder[16]

- 9th symphony (PDF): Free scores at the International Music Score Library Project.

- Original manuscript (site in German)

- The William and Gayle Cook Music Library at the Indiana University School of Music's has posted a score for the symphony.

- Text/libretto, with translation, in English and German

Other material

- EU official page about the anthem

- Analysis of the Beethoven Symphony No. 9 on the All About Ludwig van Beethoven Page

- A guided tour of Beethoven's 9th Symphony by Rob Kapilow on WNYC's Soundcheck

- Program note from the Kennedy Center with more information about the symphony's finale as it might have been, and is

- Analysis for students (with timings) of the final movement, at Washington State University

- Hinton, Stephen (Summer 1998). "Not "Which" Tones? The Crux of Beethoven's Ninth". 19th-Century Music Vol. 22 (No. 1): pp. 61–77. doi:. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0148-2076(199822)22%3A1%3C61%3AN%22TTCO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-7. Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

References

- ↑ Del Mar, Jonathan (July-December 1999). "Jonathan Del Mar, New Urtext Edition: Beethoven Symphonies 1-9". British Academy Review. Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "Ludwig van Beethoven The Nine Symphonies The New Bärenreiter Urtext Edition". Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

- ↑ Zander, Benjamin. "Beethoven 9 The fundamental reappraisal of a classic". Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "Concerning the Review of the Urtext Edition of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony". Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

- ↑ "Beethoven The Nine Symphonies".

- ↑ Rosen, Charles. "The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven". page 440. New York: Norton, 1997.

- ↑ "Beethoven Foundation - Schiller's "An die Freude" and Authoritative Translation".

- ↑ Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68. The Kennedy Center, 2006

- ↑ Steinberg, Michael. "The Symphony: a listeners guide". page 153. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ↑ Optical Recording: Beethoven's Ninth Symphony of greater importance than technology, Philips

- ↑ Kees A. Schouhamer Immink (2007). "Shannon, Beethoven, and the Compact Disc" (html). IEEE Information Theory Newsletter: 42–46. http://www.exp-math.uni-essen.de/~immink/pdf/beethoven.htm. Retrieved on 2007-12-12.

- ↑ Naxos (2006). "Ode To Freedom - Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 (NTSC)". Naxos.com Classical Music Catalogue. Retrieved on 2006-11-26. This is the publisher's catalogue entry for a DVD of Bernstein's Christmas 1989 "Ode to Freedom" concert.

- ↑ "The European Anthem". Europa.

- ↑ EUROPA - The EU at a glance - The European Anthem

- ↑ Esteban Buch: Beethoven's Ninth

- ↑ OperaResource - RealHoffmann, A Brief History of Schott

|

|||||

|

|||||