Battle of the Bulge

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

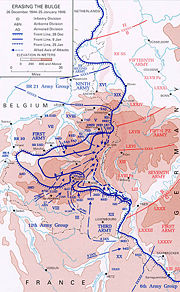

Official U.S. Army illustration: The "Front lines" (Phase lines) map (observe the Dark blue lines, including dashed lines) showing the swelling of the Bulge as the German offensive progressed East to West creating the nose-like bulge shape (salient) between the 16th and 26th of December, 1944.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ardennes Offensive (16 December 1944 – 25 January 1945) was a major German offensive launched towards the end of World War II through the forested Ardennes Mountains region of Belgium, France and Luxembourg on the Western Front. The offensive was called Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein (Translated as Operation The Guard on the Rhine or Operation "Watch on the Rhine.") by the German armed forces (Wehrmacht). This German offensive was officially named the Battle of the Ardennes[2] or the Ardennes-Alsace campaign[3] by the U.S. Army[4], but it is known to the general public simply as the Battle of the Bulge. The “bulge” was the initial incursion the Germans put into the Allies’ line of advance, as seen in maps presented in contemporary newspapers.

The German offensive was supported by subordinate operations known as Unternehmen Bodenplatte, Unternehmen Greif, and Unternehmen Währung. Germany’s planned goal for these operations was to split the British and American Allied line in half, capturing Antwerp, Belgium, and then proceeding to encircle and destroy four Allied armies, forcing the Western Allies to negotiate a peace treaty in the Axis Powers’ favour.[5]

The Germans planned the offensive with utmost secrecy, minimizing radio traffic and conducting the movement of troops and equipment under cover of darkness. Although ULTRA suggested a possible attack and the Third U.S. Army's intelligence staff predicted a major German offensive, the Germans still achieved surprise. This was achieved by a combination of Allied overconfidence, preoccupation with their own offensive plans, poor aerial reconnaissance, and the relative lack of combat contact by the First United States Army in an area considered a "quiet sector". Almost complete surprise against a weak section of the Allies’ line was achieved during heavy overcast weather, when the Allies’ strong air forces would be grounded.

German objectives ultimately were unrealized. In the wake of the defeat, many experienced German units were left severely depleted of men and equipment, as survivors retreated to the defences of the Siegfried Line. The Battle of the Bulge was the bloodiest of the battles that U.S. forces experienced in World War II; the 19,000 American dead were unsurpassed by those of any other engagement

Contents |

Background

After the breakout from Normandy at the end of August 1944, coupled with landings in southern France, the Allies advanced towards Germany faster than anticipated.[6] The rapid advance, coupled with an initial lack of deep water ports, presented the Allies with enormous supply problems. Over-the-beach supply operations using the Normandy landing areas and direct landing LSTs on the beaches exceeded planning expectations, but the only deep water port in Allied hands was at Cherbourg, near the original invasion beaches. Although the port of Antwerp, Belgium was captured fully intact (with the Germans in full flight) in the first days of September, it was not made operational until 28 November, when the estuary of the River Scheldt, which gives access to the port, had been cleared from German control. This delay was caused by failure of senior commanders Dwight D.Eisenhower and Bernard Montgomery (whose sector it was) to recognize the need to clear the estuary, amidst the wrangle over whether Montgomery or Patton in the south, would get priority. This was compounded by the priority given Operation Market Garden, which had mobilized the resources needed for expelling the German forces from the riverbanks of the Scheldt. German forces remained in control of several major ports on the English Channel coast until May 1945; those ports that did fall to the Allies in 1944 were sabotaged to deny their immediate use by the Allies. The extensive destruction of the French railroad system prior to D-Day, intended to deny movement to the Germans, proved equally damaging to the Allies as it took time to repair the system of tracks and bridges. A trucking system known as the “Red Ball Express” was instituted to bring supplies to front line troops; however, it took five times as much fuel to reach the front line near the Belgian border than was delivered. By early October, the Allies had to suspend major offensives in order to build up their supplies.

Generals Patton, Montgomery, and Omar N. Bradley each pressed for priority delivery of supplies to their own respective armies, in order to continue advancing and keeping pressure on the Germans. General Eisenhower, however, preferred a broad-front strategy—though with priority for Montgomery’s northern forces, since their short-term goal included opening the urgently-needed port of Antwerp, and their long-term goal was the capture of the Ruhr area, the industrial heart of Germany. With the Allies paused, Gerd von Rundstedt was able to reorganize the disrupted German armies into a semi-coherent defence.

Field Marshal Montgomery’s Operation Market Garden was unsuccessful and left the Allies worse off than before. In October, the Canadian First Army fought the Battle of the Scheldt, clearing the Westerschelde by taking Walcheren and opening the ports of Antwerp to shipping. By the end of the month, the supply situation was easing. The Allied seizure of the large port of Marseille in the south greatly helped as well.

Despite a lull along the front after the Scheldt battles, the German situation remained dire. While operations continued in the autumn, notably the Lorraine Campaign, the Battle of Aachen, and the fighting in the Hürtgen Forest, the strategic situation in the west changed little.

On the Eastern Front, the Soviets' Operation Bagration destroyed much of Germany's Army Group Center (Heeresgruppe Mitte) during the summer. The progress of this operation was so fast the offensive ended only when the advancing Red Army forces outran their supplies. By November, it was clear Soviet forces were preparing for a winter offensive.

Meanwhile, the Allied air offensive of early 1944 had effectively grounded the Luftwaffe (German Air Force), leaving the German Army with little battlefield intelligence and no way to interdict Allied supplies. The converse was equally damaging: daytime movement of German forces was almost instantly noticed, and interdiction of supplies combined with the bombing of the Romanian oil fields starved Germany of oil and gasoline.

The advantage for the German forces by November 1944 was that they were no longer defending all of western Europe. The front lines in the west were considerably shorter and closer to the German heartland, dramatically improving their supply problems despite Allied control of the air. Additionally, their extensive telephone and telegraph network meant that radios no longer had to be used for communications, which deprived the Allies of one of their most powerful tools, ULTRA intercepts.

Drafting the offensive

German dictator Adolf Hitler felt his armies still might be able to defend Germany successfully in the long term, if only they could somehow neutralize the Western Front in the short term. Further, Hitler believed he could split the Allies and persuade the Americans and British to sue for a separate peace, independent of the Soviet Union. Success in the West would give the Germans time to design and produce more advanced weapons (such as jet aircraft, new U-boat designs, and super-heavy tanks) and permit the concentration of forces in the East. This assessment is generally regarded as unrealistic, given Allied air superiority throughout Europe and the ability to intervene significantly in German offensive operations.

Several senior German military advisors expressed their concern that favourable weather would permit Allied air power to effectively stop any offensive action. Hitler ignored or dismissed this, though the offensive was intentionally scheduled for late autumn, when northwestern Europe is often covered by heavy fog and low-lying cloud, to minimize the Allied air advantage.

When the Allied offensive in the Netherlands (Market Garden) wound down in September 1944, at about the same time as Bagration, the strategic initiative briefly swung to the Germans. Given the reduced manpower of German land forces at the time, it was believed the best way to take advantage of the initiative would be to attack in the West, against the smaller Allied forces, rather than against the vast Soviet armies. Even the encirclement and destruction of entire Soviet armies, an unlikely outcome, would still have left the Soviets with a large numerical superiority.

In the West, supply problems were beginning to significantly impede Allied operations, even though the opening of Antwerp in November 1944 did slightly improve the situation. The Allied armies were overextended—their positions ran from southern France to the Netherlands. German planning revolved around the premise that a successful strike against thinly-manned stretches of the line would halt Allied advances on the entire Western Front.

Several plans for major Western offensives were put forward, but Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces, or OKW) quickly concentrated on two. A first plan for an encirclement maneuver called for a two-pronged attack along the borders of the U.S. armies around Aachen, hoping to encircle the Ninth and Third Armies and leave the German forces back in control of the excellent defensive grounds where they had fought the U.S. to a standstill earlier in the year. A second plan called for a classic blitzkrieg attack through the weakly-defended Ardennes Mountains, mirroring the successful German offensive there during the Battle of France in 1940, aimed at splitting the armies along the U.S.-British lines and capturing Antwerp. This plan was named Wacht am Rhein or "Watch on the Rhine", after a popular German patriotic song; this name also deceptively implied the Germans would be adopting a defensive posture in the Western Front.

Hitler chose the second plan, believing a successful encirclement would have little impact on the overall situation and finding the prospect of splitting the Anglo-American armies more appealing. The disputes between Montgomery and Patton were well known, and Hitler hoped he could exploit this perceived disunity. If the attack were to succeed in capturing the port of Antwerp four complete armies would be trapped without supplies behind German lines.

Both plans centered on attacks against the American forces; Hitler believed the Americans were incapable of fighting effectively, and that the American home front was likely to crack upon hearing of a decisive American loss. There is no evidence Hitler realized, or any of his military staff pointed out, that of all the major combatants, the United States was the least damaged and had the greatest recuperative powers.

Tasked with carrying out the operation were Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Walther Model, the commander of German Army Group B (Heeresgruppe B), and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, the overall commander of the German Army Command in the West (Oberbefehlshaber West).

Model and von Rundstedt both believed aiming for Antwerp was too ambitious, given Germany’s scarce resources in late 1944. At the same time, they felt maintaining a purely defensive posture (as had been the case since Normandy) would only delay defeat, not avert it. They thus developed alternative, less ambitious plans that did not aim to cross the Meuse River, Model’s being Operation Autumn Mist (Unternehmen Herbstnebel) and von Rundstedt’s Case Martin (Fall Martin). The two Field Marshals combined their plans to present a joint "small solution" to Hitler, who rejected it in favour of his "big solution".[7]

Planning

OKW decided by the middle of September, at Hitler’s insistence, the offensive be mounted in the Ardennes, as was done in France in 1940. Many German generals objected, but the offensive was planned and carried out. While German forces in that battle had passed through the Ardennes before engaging the enemy, the 1944 plan called for battle to occur within the forest. The main forces were to advance westward until reaching the Meuse River, then turn northwest for Antwerp and Brussels. The close terrain of the Ardennes would make rapid movement difficult, though open ground beyond the Meuse offered the prospect of a successful dash to the coast.

Four armies were selected for the operation:

- The Sixth SS Panzer Army, under Sepp Dietrich. Newly created on 26 October 1944, it incorporated the senior formation of the Waffen-SS, the 1. SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler as well as the 12. SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. Sixth SS Panzer Army was designated the northernmost attack force, with the offensive’s primary objective of capturing Antwerp entrusted to it.

- The Fifth Panzer Army under Hasso von Manteuffel, was assigned to the middle attack route with the objective of capturing Brussels.

- The Seventh Army, under Erich Brandenberger, was assigned to the southernmost attack, with the task of protecting the flank. This Army was made up of only four infantry divisions, with no large scale armoured formations to use as a spearhead unit. As a result, they made little progress throughout the battle.

- Also participating in a secondary role was the Fifteenth Army, under Gustav-Adolf von Zangen. Recently rebuilt after heavy fighting during Market Garden, it was located on the far north of the Ardennes battlefield and tasked with holding U.S. forces in place, with the possibility of launching its own attack given favourable conditions.

For the offensive to be successful, four criteria were deemed critical by the planners:

- The attack had to be a complete surprise;

- The weather conditions had to be poor to neutralize Allied air superiority and the damage it could inflict on the German offensive and its supply lines;

- The progress had to be rapid. Model had declared that the Meuse River had to be reached by day 4, if the offensive was to have any chance of success; and

- Allied fuel supplies would have to be captured intact along the way because the Wehrmacht was short on fuel. The General Staff estimated they only had enough fuel to cover one-third to one-half of the ground to Antwerp in heavy combat conditions.

The plan originally called for just under 45 divisions, including a dozen panzer and panzergrenadier divisions forming the armoured spearhead and various infantry units to form a defensive line as the battle unfolded. The German army suffered from an acute manpower shortage by this time, however, and the force had been reduced to around 30 divisions. Although it retained most of its armour, there were not enough infantry units because of the defensive needs in the east. These thirty newly rebuilt divisions used some of the last reserves of the German Army (Wehrmacht Heer). Among them were Volksgrenadier units formed from a mix of battle-hardened veterans and recruits formerly regarded as too young or too old to fight. Training time, equipment, and supplies were inadequate during the preparations. German fuel supplies were precarious—those materials and supplies that could not be directly transported by rail had to be horse-drawn to conserve fuel—the mechanised and panzer divisions would depend heavily on captured fuel. The start of the offensive was delayed from 27 November to 16 December as a result.

Before the offensive, the Allies were virtually blind to German troop movement. During the reconquest of France, the extensive network of the French resistance had provided valuable intelligence about German dispositions. Once they reached the German border, this source dried up. In France, orders had been relayed within the German army using radio messages enciphered by the Enigma machine, and these could be picked up and decrypted by Allied codebreakers to give the intelligence known as ULTRA. In Germany such orders were typically transmitted using telephone and teleprinter, and a special radio silence order was imposed on all matters concerning the upcoming offensive. The major crackdown in the Wehrmacht after the July 20 Plot resulted in much tighter security and fewer leaks. The foggy autumn weather also prevented Allied reconnaissance planes from correctly assessing the ground situation.

Thus, Allied High Command considered the Ardennes a quiet sector, relying on assessments from their intelligence services that the Germans were unable to launch any major offensive operations this late in the war. What little intelligence they had led the Allies to believe precisely what the Germans wanted them to believe—that preparations were being carried out only for defensive, not offensive operations. In fact, because of the Germans’ efforts, the Allies were led to believe that a new defensive army was being formed around Düsseldorf in the northern Rhine, possibly to defend against British attack. This was done by increasing the number of flak batteries in the area and the artificial multiplication of radio transmissions in the area. The Allies at this point thought the information was of no importance. All of this meant that the attack, when it came, completely surprised the Allied forces. Remarkably, the U.S. Third Army intelligence chief, Colonel Oscar Koch, the U.S. First Army intelligence chief, and the SHAEF intelligence officer all correctly predicted the German offensive capability and intention to strike the U.S. VIII Corps area. These predictions were largely dismissed by the U.S. 12th Army Group. It's also intriguing that Montgomery moved reserves to cover the Meuse bridges within 24 hours of the German assault.

Because the Ardennes was considered a quiet sector, economy-of-force considerations led it to be used as a training ground for new units and a rest area for units that had seen hard fighting. The U.S. units deployed in the Ardennes thus were a mixture of inexperienced troops (such as the raw U.S. 99th and 106th "Golden Lions" Divisions), and battle-hardened troops sent to that sector to recuperate (the 2nd Infantry Division).

Two major special operations were planned for the offensive. By October it was decided Otto Skorzeny, the German commando who had rescued the former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, was to lead a task force of English-speaking German soldiers in Operation Greif. These soldiers were to be dressed in American and British uniforms and wear dog tags taken from corpses and POWs. Their job was to go behind American lines and change signposts, misdirect traffic, generally cause disruption and to seize bridges across the Meuse River between Liège and Namur. By late November another ambitious special operation was added: Colonel Friedrich August von der Heydte was to lead a Fallschirmjäger (paratrooper) Kampfgruppe in Operation Stösser, a nighttime paratroop drop behind the Allied lines aimed at capturing a vital road junction near Malmedy.

German intelligence had set 20 December as the expected date for the start of the upcoming Soviet offensive, aimed at crushing what was left of German resistance on the Eastern Front and thereby opening the way to Berlin. It was hoped that Stalin would delay the start of the operation once the German assault in the Ardennes had begun and wait for the outcome before continuing.

In the final stage of preparations, Hitler and his staff left their Wolf's Lair headquarters in East Prussia, in which they had coordinated much of the fighting on the Eastern Front. After a brief visit to Berlin, on 11 December, they came to the Eagle's Nest, Hitler’s headquarters near Bad Nauheim in southern Germany, the site from which he had overseen the successful 1940 campaign against France and the Low Countries.

Initial German assault

The German assault began on 16 December 1944, at 05:30, with a massive artillery barrage on the Allied troops facing the Sixth SS Panzer Army. By 08:00 all three German armies attacked through the Ardennes. In the northern sector Dietrich’s Sixth SS Panzer Army assaulted the Losheim Gap and the Elsenborn Ridge in an effort to break through to Liège. In the center von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army attacked towards Bastogne and St. Vith, both road junctions of great strategic importance. In the south, Brandenberger's Seventh Army pushed towards Luxembourg in their efforts to secure the flank from Allied attacks.

The attacks by the Sixth SS Panzer Army’s infantry units in the north fared badly because of unexpectedly fierce resistance by the U.S. 2nd and 99th Infantry Divisions at the Elsenborn Ridge, stalling their advance; this caused Dietrich to commit his panzer forces early. Starting on 16 December, however, snowstorms engulfed parts of the Ardennes area. While having the desired effect of keeping the Allied aircraft grounded, the weather also proved troublesome for the Germans because poor road conditions hampered their advance. Poor traffic control led to massive traffic jams and fuel shortages in forward units.

The Germans fared better in the center (the 20 mile (30 km) wide Schnee Eifel sector) as the Fifth Panzer Army attacked positions held by the U.S. 28th and 106th Infantry Divisions. The Germans lacked the overwhelming strength as had been deployed in the north; but they succeeded in surrounding two regiments (422nd and 423rd) of the 106th Division in a pincer movement and forced their surrender, a tribute to the way Manteuffel’s new tactics had been applied.[8] The official U.S. Army history states: "At least seven thousand [men] were lost here and the figure probably is closer to eight or nine thousand. The amount lost in arms and equipment, of course, was very substantial. The Schnee Eifel battle, therefore, represents the most serious reverse suffered by American arms during the operations of 1944–45 in the European theater."

Further south on Manteuffel’s front the main thrust was delivered by all attacking divisions crossing the River Our, then increasing the pressure on the key road centers of St. Vith and Bastogne. Panzer columns took the outlying villages. The struggle for these villages, and transport confusion on the German side, slowed the attack to allow the 101st Airborne Division (reinforced by elements from the 9th and 10th Armored Divisions) to reach Bastogne by truck on the morning of 19 December. The fierce defence of Bastogne, in which American paratroopers particularly distinguished themselves, made it impossible for the Germans to take the town with its important road junctions. The panzer columns swung past on either side, cutting off Bastogne on 20 December but failing to secure the vital crossroads.

In the extreme south, Brandenberger’s three infantry divisions were checked after an advance of four miles (6.5 km) by divisions of the U.S. VIII Corps; that front was then firmly held. Only the 5th Parachute Division of Brandenberger’s command was able to thrust forward 12 miles (19 km) on the inner flank to partially fulfill its assigned role.

Eisenhower and his principal commanders realized by 17 December that the fighting in the Ardennes was a major offensive and not a local counter-attack, and they ordered vast reinforcements to the area. Within a week 250,000 troops had been sent. In addition, the 82nd Airborne Division was also thrown into the battle north of the bulge, near Elsenborn Ridge.

Operation Stösser

Originally planned for the early hours of 16 December, Operation Stösser was delayed for a day because of bad weather and fuel shortages. The new drop time was set for 03:00 on 17 December; their drop zone was 7 miles (11 km) north of Malmedy and their target was the "Baraque Michel" crossroads. Von der Heydte and his men were to take it and hold it for approximately twenty-four hours until being relieved by the 12th SS Panzer Division, thereby hampering the Allied flow of reinforcements and supplies into the area.

Just after midnight on 17 December, 112 Ju 52 transport planes with around 1,300 Fallschirmjägern took off amid a powerful snowstorm, with strong winds and extensive low cloud cover. As a result, many planes went off course, and men were dropped as far as a dozen kilometres away from the intended drop zone, with only a fraction of the force landing near it. Strong winds also took off-target those paratroopers whose planes were relatively close to the intended drop zone and made their landings far rougher.

By noon, a group of around 300 managed to assemble, but this force was too small and too weak to counter the Allies. Colonel von der Heydte abandoned plans to take the crossroads and instead ordered his men to harass the Allied troops in the vicinity with guerrilla-like actions. Because of the extensive dispersal of the jump, with Fallschirmjägern being reported all over the Ardennes, the Allies believed a major division-sized jump had taken place, resulting in much confusion and causing them to allocate men to secure their rear instead of sending them off to the front to face the main German thrust.

Operation Greif and Operation Währung

For Operation Greif, Otto Skorzeny successfully infiltrated a small part of his battalion of disguised, English-speaking Germans behind the Allied lines. Although they failed to take the vital bridges over the Meuse, the battalion’s presence produced confusion out of all proportion to their military activities, and rumors spread quickly. Even General Patton was alarmed and, on 17 December, described the situation to General Eisenhower as “Krauts… speaking perfect English… raising hell, cutting wires, turning road signs around, spooking whole divisions, and shoving a bulge into our defences.”

Checkpoints were set up all over the Allied rear, greatly slowing the movement of soldiers and equipment. Military policemen drilled servicemen on things which every American was expected to know, such as the identity of Mickey Mouse’s girlfriend, baseball scores, or the capital of Illinois. This last question resulted in the brief detention of General Bradley; although he gave the correct answer—Springfield—the GI who questioned him apparently believed the capital was Chicago.

The tightened security nonetheless made things harder for the German infiltrators, and some of them were captured. Even during interrogation they continued their goal of spreading disinformation; when asked about their mission, some of them claimed they had been told to go to Paris to either kill or capture General Eisenhower. Security around the general was greatly increased, and he was confined to his headquarters. Because these prisoners had been captured in American uniform, they were later executed by firing squad; this was the standard practice of every army at the time, although it was left ambiguous under the Geneva Convention, which merely stated soldiers had to wear uniforms that distinguished them as combatants. In addition, Skorzeny was aware under international law such an operation would be well within its boundaries as long as they were wearing their German uniforms when firing.[9] Skorzeny and his men were fully aware of their likely fate, and most wore their German uniforms underneath their Allied ones in case of capture. Skorzeny avoided capture, survived the war, and may have been involved with the Nazi ODESSA escape network.

For Währung, a small number of German agents infiltrated Allied lines in American uniforms. These agents were then to use an existing Nazi intelligence network to attempt to bribe rail and port workers to disrupt Allied supply operations. This operation was a failure.

Malmedy massacre

In the north, the main armored spearhead of the Sixth SS Panzer Army was Kampfgruppe Peiper, consisting of 4,800 men and 600 vehicles of the 1. SS Panzer Division under the command of Waffen-SS Oberst Joachim Peiper. Bypassing the Elsenborn ridge, at 07:00 on 17 December, they seized a U.S. fuel depot at Büllingen, where they paused to refuel before continuing westward. At 12:30, near the hamlet of Baugnez, on the height halfway between the town of Malmedy and Ligneuville, they encountered elements of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, U.S. 7th Armored Division.[10][11] After a brief battle the Americans surrendered. They were disarmed and, with some other Americans captured earlier (approximately 150 men), sent to stand in a field near the crossroads where most were shot. It is not known what caused the shooting and there is no record of an SS officer giving an execution order;[11] such shootings of prisoners of war (POWs), however, were common by both sides on the Eastern Front. News of the killings raced through Allied lines.[11] Captured SS soldiers who were part of Kampfgruppe Peiper were tried following the war for this massacre and several others during the Malmedy massacre trial.

The fighting went on and, by the evening, the spearhead had pushed north to engage the U.S. 99th Infantry Division and Kampfgruppe Peiper arrived in front of Stavelot. Peiper was already behind the timetable because it took 36 hours to advance from Eifel to Stavelot; it had taken just 9 hours in 1940. As the Americans fell back, they blew up bridges and fuel dumps, denying the Germans critically needed fuel and further slowing their progress.

Wereth 11

Another, much smaller massacre was committed in Wereth, Belgium, approximately a thousand yards northeast of Saint-Vith, on 17 December 1944. Eleven African-American soldiers, after surrendering, were tortured and then shot by men of 1. SS Panzer Division, belonging to Kampfgruppe Hansen. The identity of the murderers remains unknown, and the perpetrators were never punished for this crime.

Assault of Kampfgruppe Peiper

Peiper entered Stavelot on 18 December but encountered fierce resistance from the American defenders. Unable to defeat them, he left a smaller support force in town and headed for the bridge at Trois-Ponts with the bulk of his strength, but by the time he reached it, retreating U.S. engineers had already destroyed it. Peiper pulled off and headed for the village of La Gleize and from there on to Stoumont. There, as Peiper approached, engineers blew up the bridge, and the American troops were entrenched and ready.

Peiper's troops were cut off from the main German force and supplies when the Americans recaptured the poorly defended Stavelot on 19 December. As their situation in Stoumont was becoming hopeless, Peiper decided to pull back to La Gleize where he set up his defences waiting for the German relief force. Since no relief force was able to penetrate the Allied line, on 23 December Peiper decided to break through back to the German lines. The men of the Kampfgruppe were forced to abandon their vehicles and heavy equipment, although most of the unit was able to escape.

St. Vith

In the centre, the town of St. Vith, a vital road junction, presented the main challenge for both von Manteuffel’s and Dietrich’s forces. The defenders, led by the 7th U.S. Armored Division, and including the remaining regiment of the 106th U.S. Infantry, with elements of the 9th U.S. Armored and U.S. 28th Infantry, all under the command of General Bruce C. Clarke, successfully resisted the German attacks, thereby significantly slowing the German advance. Under orders from Montgomery, St. Vith was given up on 21 December; U.S. troops fell back to entrenched positions in the area, presenting an imposing obstacle to a successful German advance. By 23 December, as the Germans shattered their flanks, the defenders’ position became untenable, and U.S. troops were ordered to retreat west of the Salm River. As the German plan called for the capture of St. Vith by 18:00 on 17 December, the prolonged action in and around it presented a major blow to their timetable.

Bastogne

By the time the senior Allied commanders met in a bunker in Verdun on 19 December, the town of Bastogne and its network of eleven hard topped roads leading through the mountainous terrain and boggy mud of the Ardennes region were to have been in German hands for several days. By the time of that meeting, two separate west-bound German columns that were to have by-passed the town to the south and north, as well as the column coming due west had been engaged and much slowed and frustrated in outlying battles at defensive positions up to ten miles from the town proper—and were gradually being forced back onto and into the hasty defenses built within the municipality. Moreover, the sole corridor that was open (to the southeast) was threatened and it had been sporadically closed as the front shifted, and there was more confidence it would be closed than it could be held open, giving every confidence the town would soon be surrounded.

Eisenhower, realizing the Allies could destroy German forces much more easily when they were out in the open and on the offensive than if they were on the defensive, told the generals, "The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster. There will be only cheerful faces at this table." Patton, realizing what Eisenhower implied, responded, “Hell, let’s have the guts to let the bastards go all the way to Paris. Then, we’ll really cut ’em off and chew ’em up.” Eisenhower asked Patton how long it would take to turn his Third Army (located in northeastern France) north to counterattack. He said he could attack with two divisions within 48 hours, to the disbelief of the other generals present. Before he had gone to the meeting, however, Patton had ordered his staff to prepare three contingency plans for a northward turn in at least corps strength. By the time Eisenhower asked him how long it would take, the movement was already underway.[12] On 20 December, Eisenhower removed the First and Ninth U.S. Armies from Bradley’s 12th Army Group and placed them under Montgomery’s 21st Army Group.

By 21 December, the German forces had surrounded Bastogne, which was defended by the 101st Airborne and Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division. Conditions inside the perimeter were tough—most of the medical supplies and medical personnel had been captured. Food was scarce, and ammunition was so low artillery crews were forbidden to fire on advancing Germans unless there was a large concentration of them. Despite determined German attacks, however, the perimeter held. The German commander requested Bastogne's surrender.[13]When General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st, was told, a frustrated McAuliffe responded, "Nuts!" After turning to other pressing issues, his staff reminded him that they should reply to the German demand. One officer (Harry W. O. Kinnard, then a Lieutenant Colonel) recommended that McAuliffe's initial reply would be "tough to beat". Thus McAuliffe wrote on the paper delivered to the Germans: “NUTS!” That reply had to be explained, both to the Germans and to non-American Allies.[14]

Rather than launching one simultaneous attack all around the perimeter, the Germans concentrated their assaults on several individual locations attacked in sequence. Although this compelled the defenders to constantly shift reinforcements in order to repel each attack, it tended to dissipate the German numerical advantage.

Meuse River

To protect the river crossings on the Meuse at Givet, Dinant and Namur, on 19 December Montgomery ordered those few units available to hold the bridges. This led to a hastily assembled force including rear echelon troops, military police and Army Air Forces personnel. The British 29th Armoured Brigade, which had turned in its tanks for re-equipping, was told to take back their tanks and head to the area. XXX Corps in Holland began their move to the area.

The furthest westward penetration made by the German attack was by the 2nd Panzer Division of the Fifth Panzer Army, coming to less than ten miles (16 km) of the Meuse by 24 December.

Allied counter-offensive

On 23 December the weather conditions started improving, allowing the Allied air forces to attack. They launched devastating bombing raids on the German supply points in their rear, and P-47 Thunderbolts started attacking the German troops on the roads. Allied air forces also helped the defenders of Bastogne, dropping much-needed supplies—medicine, food, blankets, and ammunition. A team of volunteer surgeons flew in by glider and began operating in a tool room.

By 24 December, the German advance was effectively stalled short of the Meuse. Units of the British XXX Corps were holding the bridges at Dinant, Givet, and Namur and U.S. units were about to take over. The Germans had outrun their supply lines, and shortages of fuel and ammunition were becoming critical. Up to this point the German losses had been light, notably in armor, which was almost untouched with the exception of Peiper’s losses. On the evening of 24 December, General Hasso von Manteuffel recommended to Hitler’s Military Adjutant a halt to all offensive operations and a withdrawal back to the West Wall. Hitler rejected this.

Patton’s Third Army was battling to relieve Bastogne. At 16:50 on 26 December, the lead element of the 37th Tank Battalion of the 4th Armored Division reached Bastogne, ending the siege.

Germans strike back

On 1 January, in an attempt to keep the offensive going, the Germans launched two new operations. At 09:15, the Luftwaffe launched Operation Baseplate (Unternehmen Bodenplatte), a major campaign against Allied airfields in the Low Countries. Hundreds of planes attacked Allied airfields, destroying or severely damaging some 465 aircraft. However, the Luftwaffe lost 277 planes, 62 to Allied fighters and 172 mostly because of an unexpectedly high number of Allied flak guns, set up to protect against German V-1 flying bomb attacks, but also by friendly fire from the German flak guns that were uninformed of the pending large-scale German air operation. While the Allies recovered from their losses in just days, the operation left the Luftwaffe weak and ineffective.[15]

On the same day, German Army Group G (Heeresgruppe G) and Army Group Upper Rhine (Heeresgruppe Oberrhein) launched a major offensive against the thinly stretched, 70 mile (110 km) line of the Seventh U.S. Army. This offensive, known as Operation North Wind (Unternehmen Nordwind), was the last major German offensive of the war on the Western Front. It soon had the weakened Seventh Army, which had at Eisenhower’s orders, sent troops, equipment, and supplies north to reinforce the American armies in the Ardennes, in dire straits.

By 15 January, Seventh Army’s VI Corps was fighting on three sides in Alsace. With casualties mounting, and running short on replacements, tanks, ammunition, and supplies, Seventh Army was forced to withdraw to defensive positions on the south bank of the Moder River on 21 January. The German offensive drew to a close on 25 January. In the bitter, desperate fighting of Operation Nordwind, VI Corps, which had borne the brunt of the fighting, suffered a total of 14,716 casualties. The total for Seventh Army for January was 11,609[1]. Total casualties included at least 9,000 wounded[16]. First, Third and Seventh Armys suffered a total of 17,000 hospitalized from the cold[1].

Allies prevail

While the German offensive had ground to a halt, they still controlled a dangerous salient in the Allied line. Patton’s Third Army in the south, centred around Bastogne, would attack north, Montgomery’s forces in the north would strike south, and the two forces planned to meet at Houffalize.

The temperature during January 1945 was extremely low. Trucks had to be run every half hour or the oil in them would freeze, and weapons would freeze. The offensive went forward regardless.

Eisenhower wanted Montgomery to go on the offensive on 1 January, with the aim of meeting up with Patton’s advancing Third Army and cutting off most of the attacking Germans, trapping them in a pocket. However, refusing to risk underprepared infantry in a snowstorm for a strategically unimportant area, Montgomery did not launch the attack until 3 January, by which time substantial numbers of German troops had already managed to successfully disengage, albeit with the loss of their heavy equipment.

At the start of the offensive, the two armies were separated by about 25 miles (40 km). American progress in the south was also restricted to about a kilometer a day. The majority of the German force executed a successful fighting withdrawal and escaped the battle area, although the fuel situation had become so dire that most of the German armor had to be abandoned. On 7 January 1945, Hitler agreed to withdraw forces from the Ardennes, including the SS panzer divisions, thus ending all offensive operations.

Controversy at high command

As the Ardennes crisis developed, Montgomery assumed temporary command of the American First and Ninth Armies (which, until then, were under Bradley's command). This controversial move was approved by Eisenhower, and was intended to prevent communication and control problems between Bradley and the North flank command.[17]

On the same day as Hitler’s withdrawal order, January 7, Montgomery held a press conference at Zonhoven in which he said he had, “headed off ... seen off ... and ... written off” the Germans. “The battle has been the most interesting, I think possible one of the most tricky ... I have ever handled.” Montgomery said he had “employed the whole available power of the British group of armies ... you thus have the picture of British troops fighting on both sides of the Americans who have suffered a hard blow.”[18]

Montgomery also gave credit to the “courage and good fighting quality” of the American troops, characterizing a typical American as a “very brave fighting man who has that tenacity in battle which makes a great soldier,” and went on to talk about the necessity of Allied teamwork, and praised Eisenhower, stating, “Teamwork wins battles and battle victories win wars. On our team, the captain is General Ike.” Despite these remarks, the overall impression given by Montgomery, at least in the ears of the American military leadership, was that he had taken the lion’s share of credit for the success of the campaign, and had been responsible for rescuing the besieged Americans.

His comments were interpreted as self-promoting, particularly his claiming that when the situation “began to deteriorate,” Eisenhower had placed him in command in the north. Patton and Eisenhower both felt this was a misrepresentation of the relative share of the fighting played by the British and Americans in the Ardennes (for every British soldier there were thirty to forty Americans in the fight), and that it belittled the part played by Bradley, Patton and other American commanders. In the context of Patton and Montgomery’s well-known antipathy, Montgomery’s failure to mention the contribution of any American general beside Eisenhower was seen as insulting. Indeed, General Bradley and his American commanders were already starting their counterattack by the time Montgomery was given command of 1st and 9th U.S. Armies.'”[19] Focusing exclusively on his own generalship, Montgomery continued to say he thought the counter-offensive had gone very well but did not explain the reason for his delayed attack on 3 January. He later attributed this to needing more time for preparation on the northern front. According to Winston Churchill, the attack from the south under Patton was steady but slow and involved heavy losses, and Montgomery claimed to be trying to avoid this situation.

Montgomery subsequently recognized his error and later wrote: “I think now that I should never have held that press conference. So great were the feelings against me on the part of the American generals that whatever I said was bound to be wrong. I should therefore have said nothing.” Eisenhower commented in his own memoirs: “I doubt if Montgomery ever came to realize how resentful some American commanders were. They believed he had belittled them—and they were not slow to voice reciprocal scorn and contempt.”

Bradley and Patton both threatened to resign unless Montgomery’s command was changed. Eisenhower, encouraged by his British deputy Arthur Tedder, had decided to sack Montgomery. However, intervention by Montgomery’s and Eisenhower’s Chiefs of Staff, Major-General Freddie de Guingand, and Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith allowed Eisenhower to reconsider and Montgomery to apologize.

Strategic situation after the Bulge

Although the German advance was halted, the overall situation remained dangerous. On 6 January Churchill once again asked Stalin for support. On 12 January, the Red Army launched the Vistula-Oder Offensive in Poland and East Prussia. Soviet sources claim this was done ahead of schedule, while most Western sources doubt it, and instead claim the Soviet offensive was delayed because of the situation in the West, with Stalin waiting until both sides had militarily exhausted themselves.

The Battle of the Bulge officially ended when the two American forces met on 25 January 1945.

Aftermaths

Casualty estimates from the battle vary widely. The official U.S. account lists 80,987 American casualties, while other estimates range from 70,000 to 104,000. Most of the American casualties occurred within the first three days of battle, when two of the U.S. 106th Infantry Division’s three regiments were forced to surrender. The Battle of the Bulge was the bloodiest of the battles that U.S. forces experienced in World War II; the 19,000 American dead were unsurpassed by those of any other engagement. British losses totaled 1,400. The German High Command’s official figure for the campaign was 84,834 casualties, and other estimates range between 60,000 and 100,000. {{fact|date=December 2008))

The Allies pressed their advantage following the battle. By the beginning of February 1945, the lines were roughly where they had been in December 1944. In early February, the Allies launched an attack all along the Western front: in the north under Montgomery toward Aachen; in the center, under Courtney Hodges; and in the south, under Patton. Montgomery’s behavior during the months of December and January, including the press conference on 7 January where he downplayed the contribution of the American generals, further soured his relationship with his American counterparts through the end of the war.

The German losses in the battle were critical in several respects: the last of the German reserves were now gone; the Luftwaffe had been broken; and the German Army in the West was being pushed back.

See also

- Battle of the Bulge order of battle

- Operation Spring Awakening

References

- Ambrose, Stephen (1992). Band of Brothers. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671769227.

- Ambrose, Stephen (1998). Citizen Soldiers. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84801-5.

- Cirillo, Roger. "Ardennes-Alsace". Office of the Chief of Military History Department of the Army. Retrieved on 2008-12-06.

- Clarke, Jeffrey J; Smith, Robert Ross (1993). Riviera to the Rhine: The European Theater of Operations. Center of Military History, United States Army.

- Cole, Hugh M.. "The Ardennes:Battle of the Bulge". Office of the Chief of Military History Department of the Army. Retrieved on 2008-12-06.

- Dupuy, Trever N; David L. Bongard and Richard C. Anderson Jr. (1994). Hitler’s Last Gamble: The Battle of the Bulge, December 1944–January 1945. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-016627-4.

- Eggenberger, David (1985). An Encyclopedia of Battles: Accounts of over 1560 Battles from 1479 B.C. to the Present. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24913-1.

- Kershaw, Alex (2004). The Longest Winter. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81304-1.

- Liddell Hart, Basil Henry (1970). History of the Second World War. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.. ISBN 9780306809125.

- MacDonald, Charles B (1984). A Time For Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34226-6.

- MacDonald, Charles B. (1999). Company Commander. Burford Books. ISBN 1-58080-038-6.

- MacDonald, Charles B. (1998). The Battle of the Bulge. Phoenix. ISBN 9781857991284.

- MacDonald, Charles B. (1994). The Last Offensive. Alpine Fine Arts Collection. ISBN 1-56852-001-8.

- Marshall, S.L.A.. "Bastogne: The First Eight Days". Office of the Chief of Military History Department of the Army. Retrieved on 2008-12-06.

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2006). Panzers in Winter: Hitler’s Army and the Battle of the Bulge. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0275971155.

- Newton, Steven H. (2006). Hitler’s Commander: Field Marshal Walter Model - Hitler’s Favorite General. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo. ISBN 0306813998.

- Parker, Danny S (1991). Battle of the Bulge. Combined Books. ISBN 0-938289-04-7.

- Parker, Danny S. (1999). The Battle of the Bulge, The German View: Perspectives from Hitler’s High Command. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1853673544.

- Weinberg, Gerhard L (1995). A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521558792.

- Wilmes, David (1999). The Long Road: From Oran to Pilsen : the Oral Histories of Veterans of World War II, European Theater of Operations. SVC Northern Appalachian Studies. ISBN 9781885851130.

- Wissolik, Richard David (2005). They Say There was a War. SVC Northern Appalachian Studies. ISBN 9781885851512.

- Wissolik, Richard David (2007). An Honor to Serve: Oral Histories United States Veterans World War II. SVC Northern Appalachian Studies. ISBN 9781885851208.

- "NUTS!" Revisited: An Interview with Lt. General Harry W. O. Kinnard

- American Experience - The Battle of the Bulge - PBS Documentary, Produced by Thomas F. Lennon.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Cirillo p 53

- ↑ Cole

- ↑ Cirillo

- ↑ Eggenberger Encyclopedia of Battles) describes this battle as the Second Battle of the Ardennes.

- ↑ Battle of the Bulge

- ↑ Operation Overlord planned for an advance to the line of the Seine by D+90 and an advance to the German frontier some time after D+120.

- ↑ Danny Parker, The Battle of the Bulge, pp.95–100; Samuel Mitcham, Panzers in Winter, p.38; Steven Newton, Hitler’s Commander, pp.329–334. Wacht am Rhein was renamed Herbstnebel after the operation was given the go-ahead in early December, although its original name remains much better known.

- ↑ B. H. Liddell Hart, History of the Second World War, p. 653.

- ↑ Otto Skorzeny, Skorzeny's Special Missions (Greenhill Books, 1997) ISBN 1-85367-291-2

- ↑ Cole pp. 75 –

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 MacDonald A Time For Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge

- ↑ Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers, p 208

- ↑ "NUTS!" Revisited

- ↑ Nuts can mean several things in American English slang). In this case, however, it signified rejection, and was explained to the Germans as meaning “Go to Hell!”

- ↑ Weinberg, p 769

- ↑ Clarke and Smith, Riviera To The Rhine, p. 527

- ↑ Urban. Generals, p. 194.

- ↑ Ryan, Cornelius. The Last Battle, (1966). pp. 204-205

- ↑ Bradley, Omar. A General's Life. 1981, pp. 382-385

External links

- Battle of the Bulge - Official webpage of the United States Army.

- The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge (Hugh M. Cole), 1965

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||