Battle of Salamis

| Battle of Salamis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Persian Wars | |||||||||

Satellite image of Salamis, with the straits to the mid-right |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Greek city-states | Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Eurybiades, Themistocles |

Xerxes I of Persia, Artemisia I of Caria, Ariabignes † |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 366–378 ships a | ~1,200 shipsb 600-800 c |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 40 ships | 200 ships | ||||||||

| a Herodotus gives 378 ships of the alliance, but his numbers add up to 366.[1]; b As suggested by several ancient sources; c Modern estimates |

|||||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of Salamis (Ancient Greek: Ναυμαχία τῆς Σαλαμῖνος), was a naval battle fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Achaemenid Empire of Persia in September 480 BC in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens. It marked the high-point of the second Persian invasion of Greece which had begun in 482 BC.

To block the Persian advance, a small force of Greeks blocked the pass of Thermopylae, whilst an Athenian-dominated Allied navy engaged the Persian fleet in the nearby straits of Artemisium. In the resulting Battle of Thermopylae, the rearguard of the Greek force was annihilated, whilst in the Battle of Artemisium the Greeks had heavy losses and retreated after the loss at Thermopylae. This allowed the Persians to conquer Boeotia and Attica. The Allies prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth whilst the fleet was withdrawn to nearby Salamis Island.

Although heavily outnumbered, the Greek Allies were persuaded by the Athenian general Themistocles to bring the Persian fleet to battle again, in the hope that a victory would prevent naval operations against the Peloponessus. The Persian king Xerxes was also anxious for a decisive battle. As a result of subterfuge on the part of Themistocles, the Persian navy sailed into the Straits of Salamis and tried to block both entrances. In the cramped conditions of the Straits the great Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to manoeuvre and became disorganised. Seizing the opportunity, the Greek fleet formed in line and scored a decisive victory, sinking or capturing at least 200 Persian ships.

As a result Xerxes retreated to Asia with much of his army, leaving Mardonius to complete the conquest of Greece. However, the following year, the remainder of the Persian army was decisively beaten at the Battle of Plataea and the Persian navy at the Battle of Mycale. Afterwards the Persian made no more attempts to conquer the Greek mainland. These battles of Salamis and Plataea thus mark a turning point in the course of the Greco-Persian wars as a whole; from then onward, the Greek poleis would take the offensive. A number of historians believe that a Persian victory would have stilted the development of Ancient Greece, and by extension 'western civilisation' per se, and has led them to claim that Salamis is one of the most significant battles in human history.

Contents |

Sources

Nearly all of the sources for the account of the battle come ultimately from the Greek historian Herodotus, writing in his 'Histories'. Historically, Herodotus has often been derided, even by other ancient writers. However, recent archaeological finds have tended to confirm specific claims made by Herodotus, and have done much to restore his reputation.[2] Nevertheless, it remains true that Herodotus often appears to have exaggerated, or simply to have recounted what he was 'told' without much critical appraisal.[3]

Background

The Greek city-states of Athens and Eretria had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt against the Persian Empire of Darius I in 499-494 BC. Darius swore revenge on these two city-states, and also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece.[4] A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the re-conquest of Thrace and forced Macedon to become a client kingdom of Persia.[5]

In 491 BC, Darius sent emissaries to all the Greek city-states, asking for a gift of 'earth and water' in token of their submission to him.[6] Having had a demonstration of his power the previous year, the majority of Greek cities duly obliged. In Athens, however, the ambassadors were put on trial and then executed; in Sparta, they were simply thrown down a well.[6] This meant that Sparta was also now effectively at war with Persia.[6]

Darius thus put together a amphibious task force under Datis and Artaphernes in 490 BC, which attacked Naxos, before receiving the submission of the other Cycladic Islands. The task force then moved on Eretria, which it besieged and destroyed.[7] Finally, it moved to attack Athens, landing at the bay of Marathon, where it was met by a heavily outnumbered Athenian army. At the ensuing Battle of Marathon, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.[8]

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.[9] Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I. Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece. Since this was to be a full scale invasion, it required long-term planning, stock-piling and conscription. Xerxes decided that the Hellespont would be bridged to allow his army to cross to Europe, and that a canal should be dug across the isthmus of Mount Athos (rounding which headland, a Persian fleet had been destroyed in 492 BC). These were both feats of exceptional ambition, which would have been beyond any contemporary state.[10] By early 480 BC, the preparations were complete, and the army which Xerxes had mustered at Sardis marched towards Europe, crossing the Hellespont on two pontoon bridges.[11]

The Athenians had also been preparing for war with the Persians since the mid-480s BC, and in 482 BC the decision was taken, under the guidance of the Athenian politician Themistocles, to build a massive fleet of triremes that would be necessary for the Greeks to fight the Persians[12]. However, the Athenians did not have the manpower to fight on land and sea; and therefore combatting the Persians would require an alliance of Greek city states. In 481 BC, Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece asking for earth and water, but making the very deliberate omission of Athens and Sparta.[13] Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading states. A congress of city states met at Corinth in late autumn of 481 BC,[14] and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed. It had the power to send envoys asking for assistance and to dispatch troops from the member states to defensive points after joint consultation. This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.[15]

Initially the 'congress' agreed to defend the narrow Vale of Tempe, on the borders of Thessaly, and thereby block Xerxes's advance.[16] However, once there, they were warned by Alexander I of Macedon that the vale could be bypassed through the Sarantoporo Pass, and that the army of Xerxes was overwhelming, the Greeks retreated. [17] Shortly afterwards, they received the news that Xerxes had crossed the Hellespont. A second strategy was therefore adopted by the allies. The route to southern Greece (Boeotia, Attica and the Peloponnesus) would require the army of Xerxes to travel through the very narrow pass of Thermopylae. This could easily be blocked by the Greek hoplites, despite the overwhelming numbers of Persians. Furthermore, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea, the Athenian and allied navies could block the straits of Artemisium. This dual strategy was adopted by the congress.[18] However, the Peloponnesian cities made fall-back plans to defend the Isthmus of Corinth should it come to it, whilst the women and children of Athens had been evacuated en masse to the Peloponnesian city of Troezen.[19]

Famously, the much smaller Greek army held the pass of Thermopylae against the Persians for three days before being outflanked by a mountain path. Much of the Greek army retreated, before the Spartans and Thespians who had continued to block the pass were surrounded and killed.[20] however, when news of Thermopylae reached them, they also retreated, since holding the straits of Artemisium was now a moot point.[21]

Prelude

The Allied fleet now sailed from Artemisium to Salamis to assist with the final evacuation of Athens; en route Themistocles left inscriptions addressed to the Ionian Greek crews of the Persian fleet on all springs of water that they might stop at, asking them to defect to the Allied cause. Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities which had not surrendered, Plataea and Thespiae; before marching on the now evacuated city of Athens.[22] The Allies (mostly Peloponnesian) prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth, demolishing the single road that led through it, and building a wall across it.[23]

This strategy was flawed, however, unless the allied fleet was able to prevent the Persian fleet from transporting troops across the Saronic Gulf. In a council-of-war called once the evacuation of Athens was complete, the Corinthian naval commander Adeimantus argued that the fleet should assemble off the coast of the Isthmus in order to achieve such a blockade.[24] However, Themistocles argued in favour of an offensive strategy, aimed at decisively destroying the Persians' naval superiority. He drew on the lessons of Artemisium, pointing out that "battle in close conditions works to our advantage".[24] He eventually won through, and the Allied navy remained off the coast of Salamis.[25]

After capturing Athens, Xerxes held a council of war with the Persian fleet gathered at Phaleron. Artemisia, queen of Halicarnassus and commander of its naval squadron in Xerxes's fleet, tried to convince him to wait for the Greeks to surrender believing that battle in the straits of Salamis was an unnecessary risk.[26] Nevertheless, Xerxes and his chief advisor Mardonius pressed for an attack.[27]

With the Persian fleet now anchored opposite Salamis, information began to reach Xerxes of rifts in the allied command; the Peloponnesians wished to evacuate from Salamis while they still could. [28] Xerxes thus ordered his fleet to patrol off Salamis, blocking the southern exit. At dusk, he ordered them to obviously withdraw, in order to tempt the Allies into a hasty evacuation.[29] That evening Themistocles attempted what appears to have been a spectacular successful use of misinformation. He sent a servant, Sicinnus, to Xerxes, with a message proclaiming that Themistocles was "on king's side and prefers that your affairs prevail, not the Hellenes".[30]. Furthermore, Themistocles claimed that the Allied fleet was planning to evacuate that very night, and that to gain victory all the Persians need to do was to block the straits.[29]

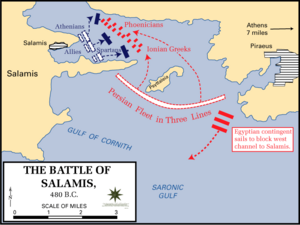

This would have been welcome news to Xerxes, and the fleet seems to have been sent out immediately. A squadron of 200 Egyptian ships was detached from the fleet, with orders to sail around Salamis and block the northern exit from the straits.[29] In fact, the Allies do not appear to have planned to evacuate that night, and were still debating what to do.[31] When Aristides, the exiled Athenian general (and former rival of Themistocles) arrived that night with news of the deployment of the Persian fleet,[32] it allowed Themistocles to present the opportunity for battle as a fait accompli to the other Allied commanders.[33]. Since there was now no hope of withdrawal, battle was the only viable course of action.[29]

The Allied navy was thus able to prepare properly for battle the forthcoming day, whilst the Persians spent the night fruitlessly at sea, searching for the alleged Greek evacuation. The next morning (possibly September 28 but the exact date is unknown), the Persians sailed in to the straits to attack the Greek fleet; it is not clear when, why or how this decision was made, but it is clear that they did in fact take the battle to the Allies.[34]

The opposing forces

The Greek fleet

Historians disagree as to the number of ships at the battle. Herodotus reports that there were 378 Greek triremes at Salamis, broken down by city-state (as indicated in the table); however, his numbers only add to 366. Macaulay notes that many editors suppose the 12 missing ships were from the Aegina garrison.[35] To these forces two more ships have to be added which defected from the Persians to the Greeks, one before Artemisium and one before Salamis.[36] According to Aeschylus, the Greek fleet numbered 310 triremes [37], while Ctesias claims that the Athenian fleet numbered only 110 triremes. According to Hyperides, the Greek fleet numbered only 220.[38] The fleet was effectively under the command of Themistocles, but nominally led by the Spartan nobleman Eurybiades, as had been agreed at the congress in 481 BC.[15] Although Themistocles claimed leadership of the fleet, the other city states with navies objected, and so Sparta (which had no naval tradition) was given command of the fleet. [15]

| City | Number of ships |

City | Number of ships |

City | Number of ships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athens[39] | 180 | Corinth[40][41] | 40 | Aegina[42] | 30 |

| Chalcis[40][42] | 20 | Megara[40][43] | 20 | Sparta[41] | 16 |

| Sicyon[41] | 15 | Epidaurus[41] | 10 | Eretria[42] | 7 |

| Ambracia[43] | 7 | Troezen[41] | 5 | Naxos[42] | 4 |

| Leucas[43] | 3 | Hermione[41] | 3 | Styra[42] | 2 |

| Cythnus[42] | 1 (1) | Ceos[42] | 2 | Melos[42][1] | (2) |

| Siphnus[42][1] | (1) | Serifos[42][1] | (1) | Croton[44] | 1 |

| Total | 366 or 378[1] (5) |

Plain numbers represent triremes; those indictated in parentheses are penteconters (fifty-oared galleys)

The Persian fleet

The much larger Persian fleet consisted according to some modern estimates of 650[45]-800[46] ships, although their original invasion force consisted of many more ships (1,207) that had since been lost due to storms in the Aegean Sea and at Artemisium. Herodotus claims they were replaced in full but only mentions 120 ships from the Greeks of Thrace and an unspecified number from the Greek islands. Aeschylus also claims 1,207 ships of which 1,000 were triremes and 207 fast ships.[47] Diodorus [48] and Lysias[49] independently claim there were 1,200 at Doriskos. The number of 1,207 (for the outset only) is also given by Ephorus[50] while his teacher Isocrates[51] claims there were 1,300 at Doriskos and 1,200 [52] at Salamis. Ctesias gives another number, 1,000 ships, (in a fragment given in Photios's book) while Plato, speaking in general terms [53] refers to 1,000 ships and more. With an average of 200 men per ship onboard, the total Persian naval force would be at least 200,000 men, without taking into account the numerous auxiliary vessels.[54]

Strategic and tactical considerations

The overall Persian strategy for the invasion of 480 BC was to overwhelm the Greeks with a massive invasion force, and complete the conquest of Greece in a single campaigning season.[55] Conversely, the Greeks sought to make the best use of their numbers by defending restricted locations and to keep the Persians in the field for as long as possible. Xerxes had obviously not anticipated such resistance, or he would have arrived earlier in the season (and not waited 4 days at Thermopylae for the Greeks to disperse).[56]

Time was now of the essence for the Persians - the huge invasion force could not be reasonably supported indefinitely, nor probably did Xerxes wish to be at the fringe of his empire for so long.[57] Thermopylae had shown that a frontal assault against a well defended Greek position was useless; with the Allies now dug in across the Isthmus, there was no chance of conquering the rest of Greece by land. However, as equally demonstrated by Thermopylae, if the Greeks could be outflanked, their small numbers of troops could easily be destroyed. Such an outflanking of the Isthmus required the use of the Persian navy, and thus the destruction of the Allied navy. In summary, if Xerxes could destroy the Allied navy, he would be in a strong position to force a Greek surrender; this seemed the only hope of concluding the campaign in that season.[57] Conversely by avoiding destruction, or as Themistocles hoped, by destroying the Persian fleet, the Greeks could avoid conquest. In the final reckoning, both sides were prepared to stake everything on a naval battle, in the hope of decisively altering the course of the war.[58]

From a tactical point of view, however, the two sides greatly differed in outlook. The Persian fleet contained contingents from some of the most illustrious sea-faring regions of the Mediterranean, including Phonecia and Egypt, and outnumbered the Greeks at least two-to-one.[56] For the Persians, a battle in the open sea, where their superior seamanship and numbers could count was the preferred type of encounter.[34] For the Greeks, with the bulk of their navy being the relatively raw Athenian navy, the only realistic hope of victory was to draw the Persians into a constricted area, where their numbers would count for little; a kind of naval Thermopylae.[24]

Therefore, by sailing into the Straits of Salamis to attack the Greeks, the Persians were playing into the Greeks' hands. It seems safe to assume that this would not have been attempted unless the Persians were confident of the collapse of the Allied navy, and thus Themistocles's subterfuge appears to have played a key role in tipping the balance in the favour of the Greeks.[34]

The Battle

Dispositions

The Persian fleet seems to have been formed of three ranks of ships; with the powerful Phoenician fleet on the right flank with Mount Aegaleo at its back; on the left flank was the Ionian fleet, while in the center were ships from Cyprus, Caria and Cilicia. In the Greek fleet, the Athenians were on the left(opposite to the Phoenicians); on the right Megareans and Aeginetians; and the rest of the fleet in the center. The Megareans and Aeginians were placed on the right (the 'position of honour') because they were considered more capable than the Athenians. [59]

Xerxes ordered a throne to be set up, on the slopes of Mount Aegaleo, to watch the battle from a clear vantage point, and so as to record the names of commanders who performed particularly well.[34] Xerxes had also positioned around 400 troops on the island known as Psyttaleia, in the middle of the straits, in order to kill or capture any Greeks who ended up there (as a result of shipwreck or grounding).[34]

The opening phases

At some early stage, a detachment of approximately 40 Corinthian ships began rowing north up the straits. This may have been the event which triggered the Persian attack, suggesting as it did that the Allied fleet was already disintegrating.[60] Instead, it seems that these ships had merely been sent to reconnoitre the northern exit from the straits, in case arrival of the encircling Egyptian detachment was imminent.[60]

As the Persians rounded the headland at the entrance to the straits, they would have become disorganised and cramped in the narrow waters.[60] Moreover, it would have become apparent that, far from disintegrating, the Greek fleet was lined up, ready to attack them. As they approached, it is claimed that they heard the Greeks singing their battle hymn (paean):[60]

- Ὦ παῖδες Ἑλλήνων ἴτε,

- ἐλευθεροῦτε πατρίδ', ἐλευθεροῦτε δὲ

- παῖδας, γυναῖκας, θεῶν τέ πατρῴων ἕδη,

- θήκας τε προγόνων:

- νῦν ὑπὲρ πάντων ἀγών.

- Forward, sons of the Greeks,

- Liberate the fatherland,

- Liberate your children, your women,

- The altars of the gods of your fathers

- And the graves of your forebears:

- Now is the fight for everything.

This was the moment when the Greeks should have begun to attack, yet initially they appeared to back their ships away as if in fear.[61] According to Plutarch, this was not only to gain better position but also in order to gain time until the early morning wind.[62] The fleet reached such a position that it was covered from the left side by the islet of Saint George and on the right by the peninsula of Kynosoura. Herodotus recounts the legend that as the fleet had backed away, they had seen an apparition of a woman, saying to them "Madmen, how far will ye yet back your ships?";[63] at this point a single ship suddenly accelerated forward towards the nearest Persian vessel and rammed it. The Athenians would claim that this was the ship of the Athenian Ameinias of Pallene; the Aeginetans would claim it as one of their ships.[61] Regardless of exactly how it began, the whole Greek line followed suit and made straight for the disordered Persian battle line.[64]

The height of the battle

The details of the rest of the battle are generally sketchy, and no one involved would have had a view of the entire battlefield.[60] Triremes were generally armed with a large ram at the front, with which it was possible to sink an enemy ship, or at least disable it by shearing off the banks of oars on one side. If the initial ramming was not successful, something similar to a land battle ensued. Both sides had marines on their ships for this eventuality; the Greeks with fully armed hoplites;[60] the Persians probably with more lightly armed Iranian infantry.[65]

Across the battlefield, as the first line of Persian ships was pushed back by the Greeks, they became fouled in the advancing second and third lines of their own ships.[66] On the Greek left, the Persian admiral Ariabignes (a brother of Xerxes)[66] was killed early in the battle; left disorganised and leaderless, the Phonecian squadrons appear to have been pushed back against the coast, many vessels running aground.[60] In the centre, a wedge of Greek ships pushed through the Persians lines, splitting the fleet in two.[60] Furthermore, the Corinthian detachment, finding that the Egyptians were not at hand, swung round at re-entered the battle, adding to the destruction.[60]

|

A king sate on the rocky brow |

| — the philhellene Lord Byron in Don Juan |

Herodotus recounts that Artemisia the queen of Halicarnassus, and commander of the Carian contingent, found herself pursued by the ship of Ameinias of Pallene. In her desire to escape, she attacked and rammed another Persian vessel, thereby convincing the Greek captain that the ship was Greek; Ameinias accordingly abandoned the chase.[68] However, Xerxes, looking on, thought that she had successfully attacked a Greek ship, and seeing the poor performance of his other captains commented that "My men have become women, and my women men".[69]

In the final stages of the battle, the remaining Persians limped back to the harbour of Phalerum, pursued by the jubilant Greeks. The Athenian general Aristides then took a detachment of men across to Psyttaleia to slaughter the garrison that Xerxes had left there.[70]

Aftermath

At least 200 Persian ships were sunk or captured. According to Herodotus, the Persians suffered many more casualties than the Greeks because most Persians did not know how to swim.[66] Xerxes, sitting on Mount Aegaleo on his golden throne, of course witnessed the carnage. Some ship-wrecked Phoenician captains tried to blame the Ionians for cowardice before the end of the battle. Xerxes, in a foul mood, and having just witnessed an Ionian ship capture an Aeginetan ship, had the Phoenicians beheaded for slandering "more noble men".[66]

In the immediate aftermath of Salamis, Xerxes attempted to build a pontoon bridge or causeway across the straits, in order to use his army to attack the Athenians; however, with the Greek fleet now confidently patrolling the straits, this proved futile.[56] Herodotus tells us that Xerxes held a council of war, at which the Persian general Mardonius tried to make light of the defeat:

Sire, be not grieved nor greatly distressed because of what has befallen us. It is not on things of wood that the issue hangs for us, but on men and horses...If then you so desire, let us straightway attack the Peloponnese, or if it pleases you to wait, that also we can do...It is best then that you should do as I have said, but if you have resolved to lead your army away, even then I have another plan. Do not, O king, make the Persians the laughing-stock of the Greeks, for if you have suffered harm, it is by no fault of the Persians. Nor can you say that we have anywhere done less than brave men should, and if Phoenicians and Egyptians and Cyprians and Cilicians have so done, it is not the Persians who have any part in this disaster. Therefore, since the Persians are in no way to blame, be guided by me; if you are resolved not to remain, march homewards with the greater part of your army. It is for me, however, to enslave and deliver Hellas to you with three hundred thousand of your host whom I will choose.[71]

Fearing that the Greeks might attack the bridges across the Hellespont and trap his army in Europe, Xerxes resolved to do this, taking the greater part of the army with him.[72] Mardonius handpicked the troops who were to remain with him in Greece, taking the elite infantry units and cavalry, to complete the conquest of Greece.[56] All of the Persian forces abandoned Attica, however, with Mardonius over-wintering in Boeotia and Thessaly; the Athenians were thus able to return to their burnt city for the winter.[56]

The following year, 479 BC, Mardonius recaptured Athens (the Allied army still preferring to guard the Isthmus). However, the Allies, under Spartan leadership eventually agreed to try and force Mardonius to battle, and marched on Attica.[73] Mardonius retreated to Boeotia to lure the Greeks into open terrain and the two sides eventually met near the city of Plataea (burnt the previous year).[73] There, at the Battle of Plataea the Greek army won a decisive victory, destroying much of the Persian army, and ending the invasion of Greece; whilst at the near-simultaneous naval Battle of Mycale they destroyed much of the remaining Persian fleet.[73]

Significance

The Battle of Salamis marked the turning point in the Greco-Persian wars. After Salamis, the Peloponnesus, and by extension Greece as an entity, was safe from conquest; and the Persians suffered a major blow to their prestige and morale (as well as severe material losses).[74] At the following battles of Plataea and Mycale, the threat of conquest was removed, and the Allies were able to go on the offensive. The Greek victory allowed Macedon]to revolt against Persian rule; and over the next 30 years, Thrace, the Aegean Islands and finally Ionia would be removed from Persian control by the Allies, or by the Athenian-dominated successor, the Delian League.[75] Salamis started a decisive swing in the balance of power toward the Greeks, which would culminate in an eventual Greek victory, severly reducing Persian power in the Aegean.[76]

Like the Battles of Marathon and Thermopylae, Salamis has gained legendary status (unlike, for instance, the more decisive Battle of Plataea), perhaps because of the desperate circumstances and the overwhelming odds.[77] A substantial number of historians hold that, along with the Battle of Marathon, Salamis is one of the most significant battle in human history.[78][79] These historians argue that if the Greeks had lost at Salamis, the ensuing conquest of Greece by the Persians would have effectively stilted the growth of 'western civilization' as we know it.[80] Certainly, the view can be taken that much of modern western society is rooted in the legacy of Ancient Greece; western thought and science began with the Greek philosophers, and ideas such as personal freedom and democracy are directly derived from this period.[77] Thus, this school of thought argues that, given the domination of much of modern history by 'western civilization', a defeat of Salamis, and an ensuing Persian domination might have changed the whole trajectory of human history.[78]

However, it is equally possible to state the reverse case. Even in the case of a Greek defeat at Salamis, the Persian conquest still might not have been completed; and even if it had, Persian domination might have proved fleeting, or might not have had a dramatic effect on Greek culture. Certainly the Ionians, despite Persian overlordship, had retained their own unique culture.[81] The point has also been made that Persian domination may even have been of benefit to some conquered territories; for instance, the oppressed neighbours of Sparta may have known more 'freedom' under a Persian regime than otherwise.[77] It is of course dangerous to speculate on potential historical outcomes; perhaps the best indicator of the effect of Salamis is to say that even at the time, the Greeks realised that Salamis had been a very significant victory.[77]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Herodotus VIII, 48

- ↑ Holland, p377

- ↑ Boardman, p532

- ↑ Holland, 171–178

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 44

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Holland, pp178–179

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 101

- ↑ Herodotus VI, 113

- ↑ Holland, p203

- ↑ Holland, pp213–214

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 35

- ↑ Holland, p217–223

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 32

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 145

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Holland, p226

- ↑ Holland, pp248–249

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 173

- ↑ Holland, pp255–257

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 40

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 18

- ↑ Herodotus, VIII, 21

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 50

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 71

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Holland, pp302–303

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 63

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 68

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 69

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 74

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Holland, pp310–315

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 75

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 78

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 79

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 80

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Holland, p318

- ↑ Macaulay, in a note accompanying his translation of Herodotus VIII, 85

- ↑ Herodotus 82

- ↑ Aeschylus, The Persians

- ↑ Lee, A Layered Look Reveals Ancient Greek Texts

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 44

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Herodotus VIII, 1

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 Herodotus VIII, 43

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 42.5 42.6 42.7 42.8 42.9 Herodotus VIII, 46

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Herodotus VIII, 45

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 47

- ↑ Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek nation) vol Β', Ekdotiki Athinon 1971

- ↑ Demetrius, 1998

- ↑ Aeschylus, The Persians

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica XI, 3

- ↑ Lysias II, 27

- ↑ Ephorus, Universal History

- ↑ Isocrates VII, 49

- ↑ Isocrates IV, 93

- ↑ Plato Laws, III 699 B

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 184

- ↑ Holland, pp209–212

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 Holland, pp327–329

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Holland, pp308–309

- ↑ Holland, p303

- ↑ Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica XI, 18

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 60.6 60.7 60.8 Holland, pp320–326

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Herodotus VIII, 84

- ↑ Plutarch. Themistocles, 14

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 84; Macaulay translation cf. Godley translation

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 86

- ↑ Herodotus VII, 184

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 Herodotus VIII, 89

- ↑ Lord Byron, Don Juan, Canto 3, 86.4

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 87

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 88

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 95

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 100

- ↑ Herodotus VIII, 97

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Holland, pp338–341

- ↑ Holland, pp333–335

- ↑ Holland, pp359–363

- ↑ Holland, p366

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 77.3 Holland, pp xvi–xxii

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Hanson, Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power

- ↑ Strauss, The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece—and Western Civilization

- ↑ Green The Year of Salamis, 480–479 B.C.

- ↑ Holland, pp148–150

Bibliography

- Herodotus, The Histories; translations by Godley and Macaulay

- Aeschylus, extract from The Persians

- Ctesias, Persica

- Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica

- Ephorus, Universal History

- Plutarch, Themistocles

- John Boardman. The Cambridge Ancient History, 1988 (ISBN 0521228042)

- Holland, Tom. Persian Fire. Abacus, 2005 (ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1)

- Green, Peter. The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970; revised ed., 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-20573-1); 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-20313-5).

- Green, Peter. Xerxes at Salamis. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970.

- Green, Peter. The Year of Salamis, 480–479 B.C. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970 (ISBN 0-297-00146-9).

- Hanson, Victor Davis. Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise of Western Power. New York: DoubleDay, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-385-50052-1); New York: Anchor Books, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 0-385-72038-6). As Why the West has Won: Carnage and Culture from Salamis to Vietnam. London: Faber and Faber, 2001 (hardcover, ISBN 0-571-20417-1); 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-571-21640-4).

- Lee, Felicia R. A Layered Look Reveals Ancient Greek Texts The New York Times, 27 Nov 2006

- Strauss, Barry. The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece—and Western Civilization. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7432-4450-8; paperback, ISBN 0-7432-4451-6).

- Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους (History of the Greek nation) vol Β', Ekdotiki Athinon 1971

- Garoufalis N. Demetrius, Η ναυμαχία της Σαλαμίνας, η σύγκρουση που άλλαξε τον ρού της ιστορίας (The battle of Salamis, the conflict that changed the flow of history), Στρατιωτική Ιστορία (Military History) magazine, issue 24, August 1998